A dilemma..

advertisement

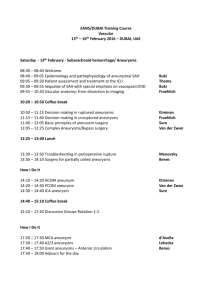

A dilemma.. Zeus: Male of undetermined age who works as King of the Gods HOPC: Sudden onset, excruciatingly severe headache Precipitating factors: Straining on the toilet PMHx: Longstanding hypertension SHx: 40 pack year smoking Hx, regular ETOH (3-4 std. drinks/day) Q: What are the critical differentials you must consider in this scenario? Hint: There are 2.. A: Zeus is pregnant with his daughter Athena in his head and is getting serious labour contractions OR… !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Subarachnoid Haemorrhage DEFINITION: ? Q: What is subarachnoid haemorrhage? Subarachnoid Haemorrhage A: DEFINITION: Spontaneous bleeding into the subarachnoid space of meninges. The area between the arachnoid mater and the pia mater. Q: This space usually contains what? A: CSF Zeus asks you: “So what caused this headache in the first place?” Q: What is the most common cause of SAH? Causes/pathophysiology A: 80-85% of cases result from rupture of an aneurysm, which tend to be located in the Circle of Willis. Risk factors for SAH include: Familial disposition to SAH – First degree relatives of SAH patients, are 3-7 times more likely to be afflicted. Metabolic syndrome: hypertension, atherosclerosis Lifestyle factors: smoking, alcohol abuse The remainder of SAH cases are due to non-aneurysmal disorders of blood vessels, e.g.: Arteriovenous malformation (AVM) rupture Angioma rupture Neoplasmic bleeding (friable new vessels) Cortical thrombosis A gallery of aneurysms Saccular (Berry) Aneurysms Most common form of cerebral aneurysm (>90%) Acquired, predisposing factors of family hx, connective tissue disorders, hypertension. Mycotic (Infective) Aneurysms Account for <1% of cerebral aneurysms. Associated with bacterial endocarditis (left heart or right heart with PFO). Dissecting (Traumatic) Aneurysms Fusiform (Atherosclerotic) Aneurysms Account for <5% of cerebral aneurysms. Account for <5% of cerebral aneurysms. Associated with atherosclerosis. Associated with trauma, usually external to brain cavity. Rupture risk Zeus hurls a lightning bolt at the ground in anger and exclaims, “But why did this happen to me?!” Q: What is the best predictor of aneurysmal rupture? (and of AVMs?) Rupture risk A: Small aneurysms good, large bad. Aneurysms with diameter less than or equal to 5mm have a 2% risk of rupture. Of those with diameter 6-10mm, 40% have already ruptured upon diagnosis. Small AVMs bad, large good. AVMs <2.5cm rupture more frequently than AVMs >5cm. Q: Why are we talking about it? A: It has very poor outcomes; death, permanent morbidity. But also, early recognition and surgical intervention can ALTER CLINICAL COURSE AND PROGNOSIS. Population is generally <60 years old; so we can make a tangible life-year difference. History Zeus finishes his tantrum and then stares at you in wonder. “But how did you know what was wrong with me as soon as I walked in the door?” A: What is the archetypal symptom of SAH? History A: Headache: Sudden onset, thunderclap, worst-ever. At its worst in mere seconds; and can be described in many different ways. 1) “Like someone smashed me over the head with a hammer” 2) “Like an explosion in my head” 3) “Like a thunderclap in my head” 4) “Like someone cleaved open my head with an axe” History Other symptoms: Symptoms relating to raised ICP and meningism: Nausea, vomiting, neck stiffness, photophobia Abnormal neurology, depending on location of bleed and local mass effects Decreased level of consciousness Seizures Q: What else could cause a sudden onset severe headache? Differential Diagnoses A: More likely Intracerebral haemorrhage (haemorrhagic stroke) Transient Ischaemic Attack (reperfusion pain) Malignant hypertension Migraine headache Less likely Meningitis Encephalitis Seizure (post-ictal phase) Examination Haemodynamic instability Hypertension and labile SBP Tachycardia (bradycardia if raised ICP) Raised ICP: Refer to previous presentation. Meningism: Neck stiffness (Nuchal rigidity), Kernig’s sign, Brudzinski’s sign. Focal neurology Cranial nerve palsies and memory loss in 25%. Oculomotor nerve palsy most common (PcomA aneurysm). Clinical grading WFNS / Hunt & Hess / (Fisher – grading on imaging). Becoming sceptical Zeus says, “Ok you’ve asked me a whole lot of questions and made my headache worse by moving me around, but how can you be sure what’s going on?” Q: What is the best first-line investigation for suspected SAH? Investigations A: CT-Brain (non-contrast) Q: If CTB shows no evidence of SAH, what is the best 2nd line investigation for detecting SAH? Investigations A: CT Angiography (CTA) – ( CTB + CTA gives >99% sensitivity at ruling out SAH) Traditionally a Lumbar Puncture is done looking for xanthochromia (as blood can be a traumatic tap). Less sensitive and can’t find aneurysm location, but advantage of less radiation and have CSF to Ix other Ddx. Other Ix include serology to inform Mx. Other imaging includes DSA (Digital Subtraction Angiography) and MRA (Magnetic Resonance Angiography) Q: What are the 2 main risks of doing a lumbar puncture without first doing a CTB? A: Risk of coning (foramen magnum brain herniation). Risk of further bleeding by dropping ICP and relieving the tamponade on the ruptured aneurysm. Just then Zeus’ wife Hera storms in and yells at you, “A mere mortal would have died by now! Hurry up and fix him!” Q: What should you have done as soon as Zeus stepped into your hospital, clutching his head and feeling unwell? Management A: Initial management – DRSABCD LOVE (Lines O2 Vitals Extra) Seek senior medical help ASAP if haemodynamically unstable/concerned (and if you’re thinking SAH, you should ALWAYS be concerned) Maintain SBP <130mmHg, beta-blockers preferred as short half-life, easily titrated. Once stabilized, Ix can be performed to confirm diagnosis If unstable, requires emergent neurosurgical treatment You manage to stabilise Zeus and calm down Hera. Hera then asks, “Ok, so you’ve stopped him dying, but you still haven’t fixed him, do something!” Q: What are the two main options for definitive management of SAH? Definitive Management Surgical Clipping Metal clip placed across the neck of the aneurysm. Modern clips are MRIsafe. Coil Embolisation Endovascularly delivered coils passed into aneurysm, fill it and cause fibrosis. Balloon or stent used. Definitive Management Surgical Clipping Hunt & Hess/WFNS Grades 1-3 Large and giant aneurysm Wide-necked aneurysms Vessels emanating from the aneurysm dome Mass effect or hematoma associated with the aneurysm Recurrent aneurysm after coil embolization Coil Embolisation Patients with poor clinical grade (i.e., Hunt and Hess / WFNS grades 4-5) Patients who are medically unstable In situations in which the aneurysm location imparts an increased surgical risk, such as cavernous sinus and many basilar tip aneurysms Small-neck aneurysms in the posterior fossa Patients with early vasospasm Cases in which the aneurysm lacks a defined surgical neck (although these are also difficult to "coil") Patients with multiple aneurysms in different arterial territories if the surgical risk is high You come to consent Zeus for a definitive procedure and he exclaims, “Well surely one of them is better, which one do you think I should have?” Q: What is the difference in outcomes between surgical clipping and coil embolisation? Definitive Management A: Surgical clipping is more definitive, there is a reduced risk of re-bleeding and of aneurysmal reformation at the clipped site. For patients that are suitable for either surgical or endovascular treatment, endovascular treatment has better overall morbidity and mortality (ISAT trial). Zeus has his procedure and is so overjoyed he gifts you an amphora of ambrosia. Hera is less easily impressed and asks, “So all those things on the consent form that you said could happen after the procedure, what were they again?” Q: What are the three most important post-procedural complications specific to SAH? Complications A: 1) Rebleed Greatest risk of re-bleeding within 24 hours post-rupture (4.1%), cumulative 14-day risk is 19%. Rebleeding mortality is 70-80%. Definitive management aims to prevent rebleeding. Rebleeding risk can be reduced by: Bed rest Analgaesia Sedation Stool softeners (to prevent Valsalvas while straining) Complications 2) Vasospasm 10-20% of SAH patients experience this. Arterial territory unrelated to aneurysm location, thought to be due to thick subarachnoid clot. Most commonly occurs at terminal ICA and proximal ACA and MCA. Mx: Traditional Mx is “Triple H”: IV fluids to achieve Hypertension, Hypervolaemia and Haemodilution. Evidence for Ca2+ channel blockers, esp. nimodipine. Statins controversial, STASH trial ongoing. Complications 3) Hydrocephalus Caused by thrombotic blockage of CSF pathways (noncommunicating) or by toxic blockage of arachnoid granulations (communicating). Mx: The presence of a CSF blockage can be detected by RISA cisternography (nuc med scan) or echoencephalography. Any thrombotic blockage can be evacuated and/or a ventricular shunt placed on repeat neurosurgical intervention. References 1) http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/content/124/2/249.full 2) http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/34/10/2540.full 3) http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/subarachnoid- haemorrhage 4) MedScape 5) OHCM 6) UpToDate