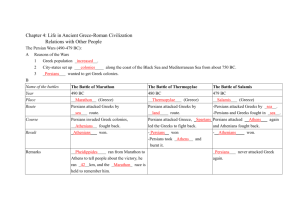

Xerxes' Invasion

advertisement

The Invention of Athens Culture, Politics, and the Persian Wars Perpetuation of Persian Wars Myth “In terms of world history, the ramifications of the Greek triumph over the Persians are almost incalculable. By repulsing the assault of the East the Hellenes charted the political and cultural development of the West for an entire century. With the triumphant struggle for liberty by the Greeks, Europe was first born, both as a concept and as a reality….The freedom which permitted Greek culture to rise to the classical models in art, drama, philosophy and historiography, this Europe owes to those who fought at Salamis and Plataea… If we regard ourselves today as free thinking people, it is the Greeks who created the condition for this.” ~H. Bengtson, History of Greece (Ottawa 1988), pg. 106 Persian Invasions and Athenian Identity Commemoration of Dead at Marathon Aeschylus’ Persians (472 BCE) Herodotus’ Histories (440s-430s BCE) Later Historical Memories and Associations Galatian Invasions of 280-279 BCE See Polybius, Histories, 2.35 Marathon Legend Marathonomachoi Aeschylus Brother Cynegeirus died at Marathon (Herodotus, 6.114) Aeschylus was veteran of Marathon; probably fought at Artemisium, Salamis, and Plataea Aeschylus’ Epitaph (see Pausanias, 1.14.5) Aeschylus, Euphorion’s son of Athens, lies under this stone dead in Gela among the white wheatlands; a man at need good in fight —witness the hallowed field of Marathon, witness the long-haired Mede. Marathon Tumulus: Monument for Fallen Creation of Persian Wars Myth Indeed upon the Asian land no longer are they subject to the Persians nor do they yet pay tribute through the master’s crushing necessity nor are they ruled falling prostrate before the king. For the kingly strength has perished. ~Aeschylus, Persians, lines 584-97 produced 472 BCE Herodotus, 7.139 At this point I am forced to declare an opinion that most people will find offensive; yet, because I think it is true, I will not hold back. If the Athenians had taken fright at the approaching danger and had left their own country, or even if they had not left it but had remained and surrendered to Xerxes, no one would have tried to oppose the King at sea. If there had been no opposition to the King at sea, what happened on land would have been this: even if the Peloponnesians had drawn many walls around the Isthmus for their defense, the Spartans would have been betrayed by their allies, not because the allies chose to do so but out of necessity as they were taken, polis by polis, by the fleet of the barbarian; thus the Spartans would have been isolated and, though isolated, would have done deeds of the greatest valor and died nobly. That would have been what happened; or else they would, before this end, have seen that all the other Greeks had medized and so themselves would have come to an agreement with Xerxes. In both these cases, all of Greece would have been subdued by the Persians….So, as it stands now, a man who declares that the Athenians were the saviors of Greece would hit the very truth. Legends of Divine Intervention Gods Support Greek Cause at Marathon Herodotus, 6.105 (Pan) Plutarch, Theseus, 35 Theseus emerges from the Underworld Pausanias 1.15.3 Theseus emerges from Underworld Addition of Marathon, Athena, Echetlus, and Heracles Herodotus, 6.105 First of all, when the generals were still within the city, they sent a herald to Sparta, one Philippides, an Athenian, who was a day-long runner and a professional. According to the story of Philippides himself, and what he told the Athenians, Pan met him on Mount Parthenium, above Tegea. Pan shouted his name, ‘Philippides,’ and commanded him to say this to the Athenians: ‘Why do you pay no heed to Pan, who is a good friend to the Athenian people, has been many times of use to you, and will be so again?’ This story the Athenians were convinced was true, and when the Athenian fortunes had again settled for the good, they set up a shrine for Pan under the Acropolis and propitiated the god himself with sacrifices and torch races, in accord with the message he had sent them. Plutarch, Life of Theseus, 35 In after times…the Athenians moved to honor Theseus as a demi-god, especially by the fact that many of those who fought at Marathon against the Persians thought they saw an apparition of Theseus in arms rushing on in front of them against the barbarians. Pausanias, 1.15.3 on Stoa Poikilē At the end of the painting are those who fought at Marathon; the Boeotians of Plataea and the Attic contingent are coming to blows with the barbarians. In this place neither side has the advantage, but the center of the fighting shows the barbarians in flight and pushing one another into the morass, while at the end of the painting are the Phoenician ships, and the Greeks killing the barbarians who are scrambling into them. Here is also a portrait of the hero Marathon, after whom the plain is named, of Theseus represented as coming up from the Underworld, of Athena and of Heracles. Legends of Divine Intervention Gods Support Greek Cause at Salamis Herodotus, 7.189-193 Boreas works against Xerxes’ fleet Poseidon destroys Persian ships off Cape Artemisium Pausanias, 1.36.1-2 Hero Cychrius appears as sea-serpent at Salamis Plutarch, Moralia, 349f-350a Artemis Mounychia (full moon) at Salamis Herodotus, Histories, 7.189 (Boreas) It is said that the Athenians had summoned Boreas, the North Wind, to help them, being so bidden to do so by a prophecy, there having been another oracle given them to ‘call in their son-in-law to help them.’ Now, according to the Greek story, Boreas married an Attic wife, Orithyia, daughter of Erectheus. The Athenians construed this in terms of a marriage connection with themselves, so the tale goes, and saw Boreas as their son-in-law. They were at their station in Chalcis in Euboea when they saw that the storm was rising, and then, or even before then, they sacrificed to Boreas and Orithyia and called on them to come to their help and to destroy the ships of the barbarians, even as before, at Athos [see 6.44]. Now, whether this was why Boreas fell upon the barbarians as they anchored there, I cannot say. But the Athenians say that Boreas came to their help before and now again, and that this action was his; and so, when they came home, they built a shrine to Boreas by the river Ilissus. Pausanias, 1.36.1 (Cychreus) In Salamis is a sanctuary of Artemis, and also a trophy erected in honor of the victory which Themistocles the son of Neocles won for the Greeks. There is also a sanctuary of Cychreus. When the Athenians were fighting the Persians at sea, a serpent is said to have appeared in the fleet, and the god in an oracle told the Athenians that it was Cychreus the hero. Herodotus 7.192 (Poseidon) Anyway, on the fourth day the storm ceased [with the Persian fleet severely damaged off the Sepiad headland]. The daywatchers on the Euboean heights ran down from their positions on the second day after the storm’s commencement and told the Greeks of all that had happened in the shipwrecking. Then the Greeks, when they learned this, made prayers to Poseidon the Savior and, having poured libations, hastened back with all possible speed to Artemisium, having formed the expectation that there would be very few ships left to oppose them. Historical Events and Artistic Innovations A Problem of Causality Artemision Zeus (or Poseidon?) Life-Size Bronze Statue, ca. 460-450 BCE National Museum, Athens, Greece Jerome Pollitt, Classical Art, and the Persian War Experience “What factors were there which might be said to have brought into being this new analysis of consciousness in Early Classical art? It seems something more than a natural evolution from what had gone on in the Archaic period and should perhaps be ascribed to both a new self-confidence and a new uneasiness which arose among many thoughtful Greeks in the wake of the Persian Wars.” ~Art and Experience in Classical Greece Temple of Olympia, East Pediment, “Seer,” ca. 460 BCE Riace Bronze, ca. 450 BCE Olympian Apollo: Severe Classicizing Style Hellenic Rationality Athenians to Spartans during Second Persian Invasion (Herodotus, 8.144) And then there is our common Greekness: we are one in blood and one in language; those shrines of the gods belong to us all in common, and there are our habits, bred of a common upbringing. Pericles’ Funeral Oration (Thucydides, 2.35-46) I shall begin with our ancestors: it is both just and proper that they should have the honor of the first mention on an occasion like the present. They dwelt in the country without break in succession from generation to generation, and handed it down free to the present time by their valor….Our constitution does not copy the laws of neighboring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. Its administration favors the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy….We cultivate refinement without extravagance and knowledge without effeminacy; wealth we employ more for use than for show, and place the real disgrace of poverty not in owning to the fact but in declining the struggle against it….In short, I say that as a city we are the school of Greece; while I doubt if the world can produce a man, who where he has only himself to depend on, is equal to so many emergencies, and graced by so happy a versatility as the Athenian. Athenian Imperial Mythologies: Athens as Ionian “Mother-City” “[Aristagoras] said this, and also said that Miletus was a colony of Athens and that, given the greatness of Athenian power, they should certainly protect the Milesians.” (Herodotus, 5.97, Ionian Rebellion) “When the appointed time comes children born of these shall come to dwell in the island cities of the Cyclades and the coastal cities of the mainland, which will give strength to my land. They shall dwell in the plains in two continents on either side of the dividing sea, Asia and Europe. They shall be called Ionians after this boy and win glory.” (Euripides, Ion, lines 1581-88, produced in 410 BCE) Athenian Imperial Mythologies: Athenians as “Autochthonous” (“Born of the Earth”) “Accordingly Attica, from the poverty of its soil enjoying from a very remote period freedom from faction, never changed its inhabitants.” (Thucydides, 1.2) “For there cohabit with us none of the type of Pelops, or Cadmus, or Aegyptus or Danaus, and numerous others of the kind, who are naturally barbarians though nominally Greeks; but our people are pure Greeks and not a barbarian blend; and so it happens that our city is imbued with a whole-hearted hatred of aliens.” (Plato, Menexenus, 245d) Greek Victory and Greek Collective Identities Centripetal Forces (Panhellenism) Validation of Greek Way of Life Articulation of to Hellenikon (see especially Herodotus, 8.144) Centrifugal Forces Athens and Sparta as Leaders Medizing States Athenian Growth and Spartan Suspicion Intellectual and Cultural Impact of Persian Wars Apotheosis of Athens Historical Consciousness (Herodotus) Hellenic Rationality/Barbarian Emotion Athenian Imperial Mythologies Athens as Ionian Metropole (“Mother-City” of Ionian Greeks) Athenian Autochthony (“Born of the Earth”) Afterlife J.B. Bury, A History of Greece (p.161), “The significance of the battle of Marathon, as a triumph for Athens, for Greece, for Europe, cannot be gainsaid...” G.W.F. Hegel " (Philosophy of History, tr. J. Sibree [New York 1956], p. 257), the battles of the Persian wars “live immortal not in the historical records of Nations only, but also of Science and of Art- of the Noble and the Moral generally. For these are World-Historical Victories; they were the salvation of culture and spiritual vigour and they rendered the Asiatic principle powerless.” John Stuart Mill (Discussions and Dissertations, vol. II [London 1859] p. 283) wrote of Marathon, “The battle of Marathon, even as an event in English history, is more important than the battle of Hastings. If the issue of that day had been different, the Britons and the Saxons might still have been wandering in the woods.” Henry Miller, The Colossus of Maroussi (New York [1941] 37), “Everywhere you go in Greece the atmosphere is pregnant with heroic deeds.... For stubbornness, courage, recklessness, daring, there are no greater examples anywhere. No wonder Durrell wanted to fight with the Greeks. Who wouldn't prefer to fight beside a Bouboulina, for example, than with a gang of sickly, effeminate recruits from Oxford or Cambridge?” Edward Said, Orientalism