The Aftermath of the Persian Wars

advertisement

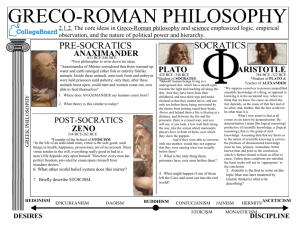

Aftermath of the Persian Wars Psycho-Cultural History and the Classical Moment? Western Thinkers on Persian Wars “[The Persian Wars] live immortal not in the historical records of Nations only, but also of Science and of Art--of the Noble and the Moral generally. For these are World-Historical Victories; they were the salvation of culture and spiritual vigor and they rendered the Asiatic principle powerless.” ~ G.W.F. Hegel, The Philosophy of History trans. Sibree (New York 1956) pg. 257 “The battle of Marathon, even as an event in English history, is more important than the battle of Hastings. If the issue of that day had been different, the Britons and the Saxons might still have been wandering in the woods.” ~J.S. Mill, Discussions and Dissertations Vol. 2 (London 1859) pg. 283 Persian Invasions and Evolution of Historical Consciousness Aeschylus’ Persians (472 BCE) Commemoration of the Dead at Marathon Herodotus’ Histories Later Historical Memories and Associations The Galatian Invasions of 280-279 BCE See Polybius, Histories, 2.35 Athens’ Role in Persian Wars Marathonomachoi Herodotus, Histories, 7.139 Marathon Tumulus “At this point I am forced to declare an opinion that most people will find offensive; yet, because I think it is true, I will not hold back. If the Athenians had taken fright at the approaching danger and had left their own country, or even if they had not left it but had remained and surrendered to Xerxes, no one would have tried to oppose the King at sea. If there had been no opposition to the King at sea, what happened on land would have been this: even if the Peloponnesians had drawn many walls around the Isthmus for their defense, the Spartans would have been betrayed by their allies, not because the allies chose to do so but out of necessity as they were taken, polis by polis, by the fleet of the barbarian; thus the Spartans would have been isolated and, though isolated, would have done deeds of the greatest valor and died nobly. That would have been what happened; or else they would, before this end, have seen that all the other Greeks had Medized and so themselves would have come to an agreement with Xerxes. In both these cases, all of Greece would have been subdued by the Persians….So, as it stands now, a man who declares that the Athenians were the saviors of Greece would hit the very truth.” Legends of Divine Intervention Herodotus 6.105 (Pan) Plutarch, Theseus, 35 Theseus emerges from the Underworld Pausanias 1.15.3 Theseus emerges from Underworld Addition of Marathon, Athena, Echetlus, and Heracles “First of all, when the generals were still within the city, they sent a herald to Sparta, one Philippides, an Athenian, who was a day-long runner and a professional. According to the story of Philippides himself, and what he told the Athenians, Pan met him on Mount Parthenium, above Tegea. Pan shouted his name, ‘Philippides,’ and commanded him to say this to the Athenians: ‘Why do you pay no heed to Pan, who is a good friend to the Athenian people, has been many times of use to you, and will be so again?’ This story the Athenians were convinced was true, and when the Athenian fortunes had again settled for the good, they set up a shrine for Pan under the Acropolis and propitiated the god himself with sacrifices and torch races, in accord with the message he had sent them.” Herodotus, Histories, 6.105 “In after times…the Athenians moved to honor Theseus as a demi-god, especially by the fact that many of those who fought at Marathon against the Persians thought they saw an apparition of Theseus in arms rushing on in front of them against the barbarians.” Plutarch, Life of Theseus, 35 “At the end of the painting are those who fought at Marathon; the Boeotians of Plataea and the attic contingent are coming to blows with the barbarians. In this place neither side has the advantage, but the center of the fighting shows the barbarians in flight and pushing one another into the morass, while at the end of the painting are the Phoenician ships, and the Greeks killing the barbarians who are scrambling into them. Here is also a portrait of the hero Marathon, after whom the plain is named, of Theseus represented as coming up from the Underworld, of Athena and of Heracles.” Pausanias, 1.15.3 Second Persian Invasion Battle at Salamis Divine Intervention at Salamis Herodotus, 7.189-193 Boreas works against Xerxes’ fleet Poseidon destroys Persian ships off Cape Artemisium Pausanias, 1.36.1-2 Hero Cychrius appears as sea-serpent at Salamis Plutarch, Moralia, 349f-350a Artemis Mounychia (full moon) at Salamis Herodotus, Histories, 7.189 (Boreas) “It is said that the Athenians had summoned Boreas, the North Wind, to help them, being so bidden to do so by a prophecy, there having been another oracle given them to ‘call in their son-in-law to help them.’ Now, according to the Greek story, Boreas married an Attic wife, Orithyia, daughter of Erectheus. The Athenians construed this in terms of a marriage connection with themselves, so the tale goes, and saw Boreas as their son-in-law. They were at their station in Chalchis in Euboea when they saw that the storm was rising, and then, or even before then, they sacrificed to Boreas and Orithyia and called on them to come to their help and to destroy the ships of the barbarians, even as before, at Athos [see 6.44]. Now, whether this was why Boreas fell upon the barbarians as they anchored there, I cannot say. But the Athenians say that Boreas came to their help before and now again, and that this action was his; and so, when they came home, they built a shrine to Boreas by the river Ilissus.” Pausanias, 1.36.1 (Cychreus) “In Salamis is a sanctuary of Artemis, and also a trophy erected in honor of the victory which Themistocles the son of Neocles won for the Greeks. There is also a sanctuary of Cychreus. When the Athenians were fighting the Persians at sea, a serpent is said to have appeared in the fleet, and the god in an oracle told the Athenians that it was Cychreus the hero.” Herodotus 7.192 (Poseidon) “Anyway, on the fourth day the storm ceased [with Persian fleet severely damaged off the Sepiad headland]. The day-watchers on the Euboean heights ran down from their positions on the second day after the storm’s commencement and told the Greeks of all that had happened in the shipwrecking. Then the Greeks, when they learned this, made prayers to Poseidon the Savior and, having poured libations, hastened back with all possible speed to Artemisium, having formed the expectation that there would be very few ships left to oppose them.” Artemision Zeus (or Poseidon?) Life-Size Bronze Statue, ca. 460-450 BCE Historical Events and Artistic Innovations A Problem of Causality Pollitt, Classical Art and the Persian War Experience “What factors were there which might be said to have brought into being this new analysis of consciousness in Early Classical art? It seems something more than a natural evolution from what had gone on in the Archaic period and should perhaps be ascribed to both a new self-confidence and a new uneasiness which arose among many thoughtful Greeks in the wake of the Persian Wars.” Art and Experience in Classical Greece New York Kouros ca. 600 BCE Anavysos Kouros ca. 530 BCE Peplos Kore ca. 530 BCE Strangford Apollo ca. 490 BCE (Lemnos?) Critias Boy (Athens) ca. 480-475 BCE Mourning Athena, Athens, ca. 470 BCE Charioteer of Delphi ca. 478 or 474 BCE Temple of Olympia, East Pediment, “Seer,” ca. 460 BCE Riace Bronze ca. 450 BCE Greek Victory and Greek Collective Identities Centripetal Forces (Panhellenism) Validation of Greek Way of Life Articulation of to Hellenikon (see especially Herodotus, 8.144) Centrifugal Forces Athens and Sparta as Leaders Medizing States Athenian Growth and Spartan Suspicion