English

advertisement

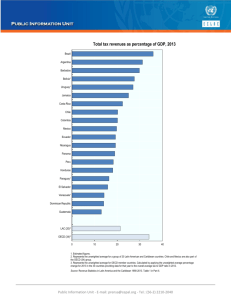

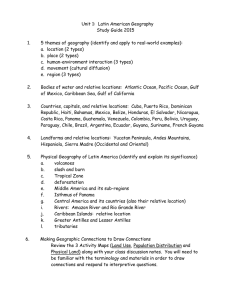

Sustainable Development in Latin America and the Caribbean Towards a post-2015 development agenda Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary Economic Commisssion for Latin America and the Caribbean Guadalajara (Mexico), April 17 2013 The normative world: two paths through Post2015 Agenda SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PATH 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment 1987 Our Common Future 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development 1994 Global Conference on the Sustainable Development of Small Island Development States 1997 Río +5 MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS PATH 1990 1990 1992 1993 1994 1995 1995 1996 1997 World Summit for Children World Conference on Education for all International Conference on Nutrition World Conference on Human Rights International Conference on Population and Development World Summit for Social Development Fourth World Conference on Women United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (HABITAT II) Kyoto Protocol 2002 International Conference on Financing for Development 2002 Río+10 Johannesburg World Summit on 2000 Millennium Summit Sustainable Development 2003 Phase One of World Summit on the Information Society 2012 Río +20 2013 Post 2015-General Assembly Different global trajectories: economics–finance-trade • • • • • • • • • 1991 –Fall of the Berlin Wall 1986-1994 – Uruguay Round 1995 – WTO succeeds GATT (outside the UN system) 1997 – liberalization of telecommunications and financial services 2001 – Doha Round: agriculture and services, TradeRelated Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Globalization: Finance and trade openness Reduced role for the State - privatizations Dominance of transnationals and global value chains Supremacy of finance over production issues MULTILATERAL POLITICAL FRAMEWORK Rio-Johannesburg-Rio Conferences: Common but differentiated responsibilities Development financing and technology transfer Explicit mechanisms for information access and citizen participation New generation of conventions with openness to the participation of main groups Prior and informed consent WTO: Levelling the playing field Free access to markets, but not to labour TRIPS: access to technology and products Consensus through concentric circles, with little citizen participation and asymmetries in developing countries Unresolved inconsistencies • Common but differentiated responsibilities versus “levelling the playing field” • Commitments versus real financial support • Technology transfer to developing countries versus concentration of technical progress in developed countries • Fair trade versus more acute trade and financial asymmetries • Overall increase in inequality: income and functional distribution • Asymmetry in real assets versus financial assets valuation • Prior and informed consent versus foreign investment in extractive sectors without consultation Towards the future we want in Latin America and the Caribbean • Fulfilment of MDGs: necessary but not the only prerequisite • From basic needs to closing structural gaps • Move from national- and developing-countries-oriented targets to universal objectives and with revived metrics • The post-2015 development agenda requires a global financing and technology transfer covenant • Concepts with a long-term, rights-based approach • The goal: more resilient, self-sufficient and balanced economies • Shared progress A decade of inter-agency work on sustainable development in the region • Regional preparatory meetings for United Nations conferences • Regional implementation forums • Regional reports on the MDGs (2005 and 2010) and Rio+20 The road so far and obstacles to the achievement of the MDGs Poverty and extreme poverty are at their lowest rates in 20 years. But LAC is still the most unequal region in the world, in spite of some recent progress in reducing income inequality LATIN AMERICA: POVERTY AND INDIGENCE, 1980-2012 a (Percentages) Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of special tabulations of household surveys conducted in the respective countries. a Estimates for 18 countries in the region plus Haiti. The figures at the top of the bars represent the percentage and total number of poor people (indigent plus non-indigent poor). The figures cited for 2011 and 2012 are projections. LATIN AMERICA AND OTHER REGIONS OF THE WORLD: GINI CONCENTRATION COEFFICIENT, AROUND 2009 a Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of special tabulations of data from household surveys conducted in the respective countries; World Bank, World Development Indicators [online]. a The regional data are expressed as simple averages, calculated using the latest observation available in each country for the 2000-2009 period. b Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Progress towards MDGs 2-7 • In education (MDG 2): high coverage and access to primary education (90%) but the quality needs to be improved and the focus must shift to secondary education. • Gender gaps (MDG 3): gender equality in education but more is needed to boost autonomy in the economic (income and property), physical (reproductive health) and political (access to decision making) spheres. • Child mortality (MDG 4): sharp reduction –from 42 deaths per 1000 live births to 16. • Maternal mortality (MDG 5): most countries will not reach the goal. Early warning: adolescent pregnancy in poor households. • HIV/AIDS (MDG 6): the prevalence of HIV in adult population has stabilized, but the situation of younger people is worrisome due to lack of knowledge about the disease and its prevention. • Environmental sustainability (MDG 7): the consumption of ozonedepleting substances has diminished, protected areas have increased, coverage of potable water (98%) and sanitation services (85%) has improved. But LAC has the highest deforestation rates and carbon dioxide emissions have grown steadily. Latin America and the Caribbean: quantifying the set of targets Source:: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of CEPALSTAT and special tabulations of data from household surveys conducted in the respective countries. MDG 8: Global Partnership for Development, the goal for which the region lags furthest behind AVERAGE TARIFFS IMPOSED BY DEVELOPED MARKET ECONOMIES ON AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS FROM DEVELOPING AND LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES (Percentages) MONTHLY AVERAGE COST OF 1 MBPS OF FIXED BROAD BAND (Percentages of GDP per capita) ESTIMATES OF AGRICULTURAL SUBSIDIES IN DEVELOPED COUNTRIES (Billions of dollars and percentage of GDP) AID FOR TRADE BY REGION (Billions of dollars at 2009 prices) The countries with the highest poverty rates need between 3% and 4% of GDP to close the gap LATIN AMERICA (18 COUNTRIES): POVERTY GAPS, AROUND 2011 Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of official figures from the respective countries. Providing universal primary education costs between 0.5% and 0.04% of GDP LATIN AMERICA (SELECTED COUNTRIES): ESTIMATED COST OF ACHIEVING UNIVERSAL PRIMARY EDUCATION Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)/ Organization of Ibero-American States for Education, Science and Culture (OEI), “Metas educativas 2021: estudio de costos”, Project Documents, No. 327 (LC/W.327), Santiago, Chile, July 2010. a Ibero-American countries (excluding Spain and Portugal). Social progress transcends social policies • Sound macroeconomic management helps to curb social losses during crises and boosts investment and productivity(debt, reserves, exchange rate) • Low inflation rates attenuate vulnerability to volatile international prices of primary goods and food products • More balanced public finances build fiscal space for sustaining public spending and consolidating social policies • Investment and savings: fixed capital formation, infrastructure, innovation • Strong, sustained economic growth boosts formal job creation and labour income • Employment with rights is the key to equality Towards a sustainable development agenda in Latin America and the Caribbean How to move from MDGs to SDGs? The current model is unsustainable • Economic growth is not enough: growth is needed for equality just as equality is needed for growth • Poverty reduction is not enough if structural inequalities based on gender, ethnicity and territory persist; • Higher productivity is not enough unless it is associated with innovation and high value added, decent jobs, sustainable use of natural resources lower carbon intensity and reduced waste; • It is not enough to provide education unless it is quality education and provides entry into the labour market; • It is not enough to have gender education parity if women do not have access to the labour market on an equitable basis and full physical and political autonomy and empowerment; • Higher social spending by the State is not enough unless development is underpinned by sound macroeconomic fundamentals; • It is not enough to have a targeted welfare policy if it is not accompanied by public policy for universal social protection; • It is not enough to act sporadically against environmental degradation without a paradigm shift in production and consumption. A structural change is necessary Inequality Productivity For the first time in recent history there have been advances in combating inequality Closing the external gap (with the technological frontier) and the internal gap (between sectors and actors) International linkages Risk of “reprimarization” of the export structure, with low value added and little investment in technology Environmen -tal sustainabiit y Move towards sustainable production and consumption patterns Taxation Regressive tax systems; weak noncontributor y pillar Investmen t Investment, at 22.9% of GDP, is insufficient for developmen t • Lifting low-income countries out of poverty calls for the equivalent of 2.5% of world GDP. Lifting only Latin America and the Caribbean, a middle income region ($ 10,000 per capita PPP), to the income level of developed countries ($ 38,000) is equivalent to 19% of global GDP. Lifting all upper middle income countries to a high income level would require the equivalent of 85% of world GDP. • Apart from the inequities concealed by averages, and even disregarding the future costs of violence, undernutrition, climate change, among others, the current development model will be unable to generate this income growth The current growth rate is not enough LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: PER CAPITA GROWTH RATE, CURRENT ACCOUNT BALANCE AND FISCAL BALANCE, 1950-2010 6% 5% 4% 3% 2% 1% 0% -1% -2% -3% -4% -5% Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). 2012 2010 2008 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996 1994 1992 1990 1988 1986 1984 1982 1980 1978 1976 1974 1972 1970 1968 1966 1964 1962 1960 1958 1956 1954 1952 -6% The heterogeneous production structure reproduces inequalities, concentrating employment in low-productivity sectors LATIN AMERICA (18 COUNTRIES): STRUCTURAL HETEROGENEITY INDICATORS, AROUND 2009 (Percentages) The region has remarkable assets, but also weaknesses Assets • Better macroeconomic indicators: international reserves, low public debt, low inflation • Poverty has fallen • Abundant natural resources: – One third of arable land and freshwater reserves – around 31% of the production of biofuels and 13% of oil production – Share of production: 47% of copper, 28% of molybdenum and 23% of zinc – 48% of world output of soybean, 31% in the case of meat , 23% for milk and 16 % for maize – 20% of natural forest area and rich biodiversity Weaknesses • • • • • Production and export structure based on static comparative advantages (linked to natural resources) Lags in innovation, science and technology Low investment in infrastructure High labour-market informality Lack of mechanisms for asserting ownership of natural resource productivity gains The production structure remains stuck on a technically less dynamic path LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: EXPORT STRUCTURE BY TECHNOLOGY INTENSITY, 1981-2010 a (Percentages of the total) Source: ECLAC, on the basis of United Nations Commodity Trade Database (COMTRADE). a Cuba and Haiti not included. Data for Antigua and Barbuda refer only to 2007, and data for the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela only to 2008; data for Honduras do not include 2008; data for Belize, Dominican Republic, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Suriname and Grenada (exports only) do not include 2009. The current style of development shows a strong correlation between GDP growth, energy consumption and pollutant emissions LATIN AMERICA: PER CAPITA GDP AND PER CAPITA ENERGY CONSUMPTION, 2008 a (Kilograms of oil equivalent and 2005 purchasing power parity dollars) Lack of education reproduces and perpetuates social inequalities and poverty LATIN AMERICA (18 COUNTRIES): MONTHLY LABOUR INCOME OF THE EMPLOYED POPULATION, BY AGE GROUP AND LEVEL OF SCHOOLING (Dollars at 2000 prices, PPP) Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Characteristic diseases of poverty and wealth coexist: undernutrition and overweight in children LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: UNDERNUTRITION AND OVERWEIGHT IN CHILDREN UNDER AGE 5, 2000-2009 (Percentages) Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Urgent need to close gaps in social protection systems LATIN AMERICA (14 COUNTRIES): POPULATION LIVING IN HOUSEHOLDS WITHOUT SOCIAL SECURITY MEMBERSHIP AND WHICH DO NOT RECEIVE ANY PENSION OR PUBLIC WELFARE TRANSFERS, BY INCOME QUINTILE, 2009 (Percentages) Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Implementation mechanisms Closing these gaps calls for a fiscal covenant that raises the tax burden and makes the tax structure more progressive INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON OF THE LEVEL AND STRUCTURE OF THE TAX BURDEN VARIOUS YEARS BETWEEN 2002 AND 2010 (Percentages of GDP) Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), International Monetary Fund (IMF) a. For most of Latin America, the coverage relates to central government, except for Argenitina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica and Plurinational State of Bolivia. Consolidate social policies through public spending – Public spending reached 29.7% of GDP, and became more progressive and less procyclical – Social spending also grew as a percentage of GDP (18.6%) and of overall public spending (62.6%) LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN (21 COUNTRIES): PUBLIC SOCIAL SPENDING AS A SHARE OF TOTAL SPENDING, 1991-1992 TO 2009-2010 a (Percentages of GDP and of total public spending) LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN (21 COUNTRIES): PUBLIC SOCIAL SPENDING BY TYPE, 1991-1992 TO 2009-2010 a (Percentages of GDP) Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), social expenditure database. a The figures above the bracket signs represent the increase in spending in percentage points between the periods 1991-1992 and 2009-2010. The pending challenge: financing for sustainable development LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: MAIN EXTERNAL FINANCING FLOWS, 1990-2012 (Percentages of GDP) Source:: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of official data from the countries, the International Monetary Fund and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Two innovative financing mechanisms are on the table Global taxes Global Funds • Tax on financial transactions • On international transactions and operations • Between 0,01% and 0,1% • Potential charge could be 0,5%, and 2,4% of global GDP, applied to developed countries • Green taxes • Air transportation • On fossil fuels • Total revenue could amount to between US$ 60 and US$ 130 billion per year •International financial services • Mechanism to securitize future ODA flows, which can mobilize up to US$ 500 billion in additional ODA • Special Drawing Rights • Instruments to finance the provision of global public goods: environmental, health and education and humanitarian aid • Grants, loans and equity financing amounting to US$ 7 billion could be transferred annually to developing countries A regional reading of the post-2015 agenda 1. The focus must continue to be on the remaining lags in achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). 2. The region is changing and facing emerging issues: energy, demography, urbanization, disasters and citizen security. 3. Addressing new challenges as well as old ones calls for a new development model based on a structural change for equality and environmental sustainability to close structural gaps. – Increased labour productivity with decent employment and full access to labour rights – Educational opportunities that permit entry into the labour market, build greater civic awareness and informed political participation and contribute to better integration in society. – Equality, in particular, physical and economic autonomy, and empowerment for women – Environmental Sustainability with full internalization of externalities. A regional reading of the post-2015 agenda 4. Minimum levels of well-being have risen: good-quality, rightsbased universalist State policies: progress towards a higher level of civilization. 5. Policy and institutions matter: regulation, taxation, financing and governance of natural resources that give the right signals to the private sector , which has co-responsibility for the development we seek 6. Better measuring is required: + GDP, national accounts that reflect actual production costs 7. Global governance for sustainable development must be built: effective decision-making forums with the participation of society. • Fair trade, technology transfer and international financial reform • New financing mechanisms, 8. Build regional density and promote South-South cooperation to strengthen the instruments of social participation. Equality is the objective, structural change the way, and politics the instrument THE CRITICAL ROLE OF THE REGIONAL SPACE • Complementarities between global and regional institutions, in a heterogeneous international community • Protection of the weaker players • A greater sense of belonging to regional and subregional institutions • With interdependence, autonomy shifts to the subregional and regional levels • Provision of public goods through a network of global and regional institutions • Deeper integration ...... but this means overcoming the tendency of the global order to cause disintegration New equation: State-market-society The public space as a collectivity of interests and not as an area for State or national influence Political agreements for a new social and intergenerational contract with defined responsibilities, protection of rights and systems of accountability Enhancing a culture of collective development based on tolerance for differences and diversity Strategic vision and long-term development from within, promoting agreements between stakeholders involved in production State policies, not only at the government or administrative level, but also in terms of institutions Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary Economic Commission for latin America and the Caribbean