WCET Preserving Hardware Prefetch for Many-Core

advertisement

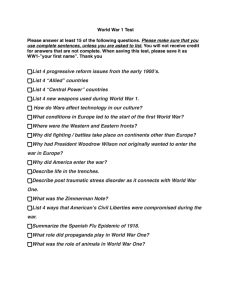

Improving The Average-Case Using Worst-Case Aware Prefetching Jamie Garside Neil C. Audsley RTNS Versailles 2014 Background Theory System Design Experimental Evaluation Conclusions & Further Work RTNS Versailles 2014 2 Background Theory System Design Experimental Evaluation Conclusions & Further Work RTNS Versailles 2014 3 Modern Embedded Systems ‣ Due to the ever-increasing performance and memory requirements, modern embedded systems are starting to utilise multi-core systems with shared memory. ‣ ‣ Shared memory is typically a large off-chip DDR memory, rather than smaller, faster on-chip memories In order to be used in a real-time context, shared memory requires some form of arbitration ‣ Techniques do exist to analyse standard, non-arbitrated memory controllers in a shared context, although these do not guarantee any safety. RTNS Versailles 2014 4 Shared Memory Arbitration ‣ Shared memory arbitration is typically achieved through a large, monolithic arbiter next to memory. ‣ ‣ ‣ E.g. TDM, frame-based or credit-based arbitration. Tasks are typically given a static bandwidth allocation in order to access memory. ‣ Given this bandwidth allocation, the worst-case response time of a memory transaction can be bounded, since the maximum interference is known. ‣ Coupled with a model of the processor, a worst-case execution time can be ascertained and bounded But… RTNS Versailles 2014 5 Shared Memory Arbitration ‣ A static bandwidth bound may not be suitable for the whole life-cycle of a system. ‣ E.g. if a task requires a lot of memory bandwidth in the first 10% of its run-time, the bandwidth bound for the whole life-cycle must be high. ‣ Dynamic bounds can be used, although this complicates system analysis. ‣ Many arbiters can be run in work conserving mode in order to improve the average-case in these cases. ‣ ‣ If a task’s bound has been exhausted, issue requests at the lowest priority level, which will be accepted only if no other tasks are requesting. Work-conservation is only useful if there is actually some data that needs fetching… RTNS Versailles 2014 6 So…Prefetch! ‣ In an ideal scenario, the memory controller should never be idle. ‣ ‣ We can use prefetch to start fetching data that might be required by a processor ahead of time, such that it arrives into the cache of the processor just as it is required. ‣ ‣ There is likely always something it could be doing in order to improve the average-case. For example, if the processor has requested the data at addresses A, A+1 and A+2, it will likely require the data at address A+3 in the near future, and so it should be fetched If the data was deemed useful by the processor, then the processor/cache can notify the prefetcher of this using a “prefetch hit” message, and an access for the next data (e.g. A+4) can be dispatched. RTNS Versailles 2014 7 But… ‣ ‣ This technique is typically not used in real-time systems. ‣ Dynamically issuing memory requests on behalf of processors complicates system analysis due to the inherently random behaviour. ‣ Inserting data directly into a processor’s cache may displace useful cache data, effectively invalidating any cache analysis. We present a prefetcher design and analysis methodology which can allow a prefetcher to be utilised within a hard real-time system without harming the worst-case execution time of the system. RTNS Versailles 2014 8 Background Theory System Design Experimental Evaluation Conclusions & Further Work RTNS Versailles 2014 9 Prefetching ‣ In order to prevent the prefetcher from being able to harm the worstcase by issuing a request when it is not appropriate, a feedback mechanism is utilised. ‣ The arbiter can notify the prefetcher of available bandwidth using a prefetch “slot”. ‣ ‣ ‣ This is simply a blank packet transmitted from the arbiter to the prefetcher. The prefetcher can then either fill in this packet or ignore it. A prefetch slot is generated whenever a processor should be making a memory request (from the perspective of the system analysis), but isn’t. This can happen in two places: RTNS Versailles 2014 10 Prefetch Hit Feedback ‣ The first, and most obvious of these is prefetch hit feedback. ‣ Take a task as a stream of accesses to memory addresses (M1, M2, M3…), separated by amounts of computation (T1, T2, T3…). ‣ If a standard memory fetch has already been prefetched, it is effectively removed from this access stream. ‣ On access to this data, the cache will generate a prefetch hit notification. ‣ When this data is used by the processor, the memory request that would have taken place without a prefetcher no longer takes place, hence a prefetch slot can be dispatched. RTNS Versailles 2014 11 Work-Conservation ‣ Similar to work conservation, a prefetch slot can be dispatched whenever a processor isn’t fully utilising its bandwidth bound. ‣ As an example, in a non-workconserving TDM system, if processor is not making a request when it enters an active period, a prefetch slot can be dispatched instead. St Rq Rq Rq ‣ All other processors would be blocked anyway due to the nature of TDM. ‣ The current processor has missed its TDM window anyway, hence must wait for its window to re-start and is thus blocked. RTNS Versailles 2014 12 Impact on WCET Analysis ‣ ‣ Since the arbiter is notifying the prefetcher of slack time in the system, the worst-case execution time analysis need not change. ‣ Assuming that the worst-case response time of memory does not depend upon the ordering of requests. ‣ This scheme effectively exploits the worst-case blocking figures that a task can experience when it would normally be making a memory request. Since prefetch slots are generated at the same point that memory arbitration would take place, and at the same time, then the timing behaviour of the system remains the same. RTNS Versailles 2014 13 Background Theory System Design Experimental Evaluation Conclusions & Further Work RTNS Versailles 2014 14 Implementation ‣ A system based on this theory was implemented using the Bluetree network-on-chip. ‣ This separates the inter-processor communication and memory communication by using separate networks for both. ‣ Since memory traffic does not need to communicate between processors, a tree structure is used to connect processors to memory, with a set of multiplexers at each level of the tree. ‣ Also included is a prefetch cache. This is a simple, small direct-mapped cache simply to store prefetches in order to prevent a prefetch displacing any useful cache information. RTNS Versailles 2014 15 Bluetree Arbitration ‣ In order to be timing predictable, each multiplexer in the tree contains a small arbiter. ‣ Each input to the multiplexer has an implicit priority (e.g. left hand side is high priority). ‣ The arbiter encodes a “blocking counter”. This is how many times a lowpriority packet has been blocked by a high-priority packet. B=0 HP1 LP1 ‣ When this reaches a pre-determined value m, a low-priority packet is given priority over a high-priority packet RTNS Versailles 2014 16 Bluetree Arbitration ‣ In order to be timing predictable, each multiplexer in the tree contains a small arbiter. ‣ Each input to the multiplexer has an implicit priority (e.g. left hand side is high priority). ‣ The arbiter encodes a “blocking counter”. This is how many times a lowpriority packet has been blocked by a high-priority packet. B=1 HP2 LP1 ‣ When this reaches a pre-determined value m, a low-priority packet is given priority over a high-priority packet RTNS Versailles 2014 17 Bluetree Arbitration ‣ In order to be timing predictable, each multiplexer in the tree contains a small arbiter. ‣ Each input to the multiplexer has an implicit priority (e.g. left hand side is high priority). ‣ The arbiter encodes a “blocking counter”. This is how many times a lowpriority packet has been blocked by a high-priority packet. B=2 HP3 LP1 ‣ When this reaches a pre-determined value m, a low-priority packet is given priority over a high-priority packet RTNS Versailles 2014 18 Bluetree Arbitration ‣ In order to be timing predictable, each multiplexer in the tree contains a small arbiter. ‣ Each input to the multiplexer has an implicit priority (e.g. left hand side is high priority). ‣ The arbiter encodes a “blocking counter”. This is how many times a lowpriority packet has been blocked by a high-priority packet. B=0 HP3 LP2 ‣ When this reaches a pre-determined value m, a low-priority packet is given priority over a high-priority packet RTNS Versailles 2014 19 Bluetree Slot Dispatching ‣ Slot dispatching can be done in much the same way as detailed previously. ‣ B=0 HP1 When a processor would normally be making a request, a slot can be dispatched instead. ‣ In this context, if a low-priority packet is relayed and there is nothing blocking it, then a prefetch slot should be dispatched instead ‣ Similarly, if m high-priority packets have been dispatched and no low-priority packets are waiting, a prefetch slot should be dispatched RTNS Versailles 2014 20 Bluetree Slot Dispatching ‣ Slot dispatching can be done in much the same way as detailed previously. ‣ B=1 HP2 When a processor would normally be making a request, a slot can be dispatched instead. ‣ In this context, if a low-priority packet is relayed and there is nothing blocking it, then a prefetch slot should be dispatched instead ‣ Similarly, if m high-priority packets have been dispatched and no low-priority packets are waiting, a prefetch slot should be dispatched RTNS Versailles 2014 21 Bluetree Slot Dispatching ‣ Slot dispatching can be done in much the same way as detailed previously. ‣ B=2 HP3 ST When a processor would normally be making a request, a slot can be dispatched instead. ‣ In this context, if a low-priority packet is relayed and there is nothing blocking it, then a prefetch slot should be dispatched instead ‣ Similarly, if m high-priority packets have been dispatched and no low-priority packets are waiting, a prefetch slot should be dispatched RTNS Versailles 2014 22 Prefetcher Design ‣ The prefetcher is a plain stream prefetcher, implemented as a global prefetcher at the root of the tree. ‣ If a processor has requested the memory at addresses A, A+1 and A+2, it will fetch A+3 on behalf of the processor. If this is a prefetch hit, it will then fetch A+4. ‣ Its position at the root enables it to obtain prefetch slots from all processors, allowing it to perform a prefetch on behalf of any processor when a slot is received. RTNS Versailles 2014 23 Background Theory System Design Experimental Evaluation Conclusions & Further Work RTNS Versailles 2014 26 Implemented Design ‣ This design was implemented on a 16-core Microblaze system on a Xilinx VC707 evaluation board, with a 1GB off-chip DDR3 memory module. ‣ Each processor and the memory interconnect was running at 100MHz. The memory controller was clocked at 200MHz. ‣ The memory interconnect was running with m=3, i.e. a low-priority packet can be blocked by at most three high-priority packets. RTNS Versailles 2014 27 Evaluation Methodology ‣ The system was evaluated using two hardware configurations ‣ 1) Sixteen systems, where in each a single processor was connected to one of the possible connections on the tree. The rest were then synthetic traffic generators which issued a memory request every cycle in order to simulate a fully loaded tree. ‣ 2) Sixteen Microblaze processors, all connected to the tree. ‣ The system was then evaluated using two software stacks: ‣ 1) Software traffic generators. These issued requests for subsequent cache lines with a delay between each fetch. ‣ 2) A selection of benchmarks from the TACLeBench suite. RTNS Versailles 2014 28 S/W Traffic Generators in High-Load System Index 0 Index 2 ‣ The prefetcher can make an improvement to the execution time of the traffic generators in most systems. ‣ As the delay reduces, prefetches start to become coalesced with their demand accesses, explaining noisy behaviour for Index 0. ‣ In Index 12, the prefetch off “steps” are caused by blocking on the tree. RTNS Versailles 2014 29 S/W Traffic Generators in High-Load System Index 12 Index 13 At higher indices (i.e. lower priority), the additional blocking leads to larger “steps”. ‣ ‣ ‣ The prefetch on line exhibits some “spikes” too. These are when a prefetch cannot be coalesced with its demand access, hence there is a performance degradation. Eventually, at higher indices and higher loads, the prefetcher is ineffective. ‣ There is so much blocking that a prefetch slot cannot be dispatched before its corresponding memory access. RTNS Versailles 2014 30 S/W Traffic Generators in 16-Core System Index 0 Index 2 ‣ The lines in a 16-core system show similar results. ‣ Due to an increase in the available bandwidth, the improvement brought about by the prefetcher can still be seen with a lower delay. RTNS Versailles 2014 31 S/W Traffic Generators in 16-Core System Index 12 ‣ Index 13 Even at higher indices, the prefetcher is still effective. ‣ There are enough prefetch slots dispatched such that prefetches can always be dispatched. The “step” effect is still present, but not as apparent. ‣ ‣ This is simply because there is more bandwidth available, hence less blocking in the “prefetch off” case. RTNS Versailles 2014 32 TACLeBench on High-Load System ‣ TACLeBench shows a good speedup for many tasks. ‣ Quite a few tasks show no speedup for CPUs 7, 11 and 13. These CPUs have the highest amount of blocking in the system, hence typically a prefetch slot cannot be dispatched before the processor requests normal data. ‣ basicmath and rijndael have large math routines exceeding I-Cache size, hence are good for prefetch. ‣ crc and sha have large input data, larger than D-Cache, hence are also good for prefetch. ‣ The rest are mostly computation dominated, although can still benefit from prefetch. RTNS Versailles 2014 33 TACLeBench on 16-Core System ‣ Sadly, prefetch is not good for all tasks. ‣ The time between memory requests in crc and basicmath is large enough that the prefetcher can still be useful ‣ For some benchmarks, such as rijndael and gsm, the computation time between requests is so small, that a prefetch gets dispatched just after the data has already been fetched, hence contributes to a performance degradation. ‣ ‣ Note that the execution time is still better than the worst-case, however. Other tasks are still improved, but not by as much due to the lower amount of contention on the tree. RTNS Versailles 2014 34 Background Theory System Design Experimental Evaluation Conclusions & Further Work RTNS Versailles 2014 35 Conclusions & Further Work ‣ We present a prefetcher that can be used within the context of realtime embedded systems without harming the worst-case execution time. ‣ Many of the issues with the prefetcher in real-world applications arise from prefetches being dispatched too late. Typically, this can be fixed by fetching further ahead of the stream. ‣ Adaptive techniques can be used, e.g. Srinath et al 2007 propose a prefetcher that adapts its parameters based on the accuracy and timeliness of prefetches. ‣ In the tree-based system, we can also turn off prefetch slot generation at certain levels in order to rate limit the number of prefetches which are generated. RTNS Versailles 2014 36 Conclusions & Further Work ‣ It is also possible to utilise the prefetcher in order to improve the worstcase execution time. ‣ The prefetcher can either be allocated a bandwidth bound, which can be rolled into the system analysis, or the number of slots which may be generated from a processor’s lack of requests may be able to be ascertained. ‣ Using this, the worst-case inter-prefetch time can be derived. This can then be used to ascertain when a prefetch will be dispatched for a given reference stream, in the worst case, and hence be rolled into the worst-case execution time analysis to reduce the WCET of a task. RTNS Versailles 2014 37 Any Questions? RTNS Versailles 2014 38