4. major impacts of ecx on coffee marketing

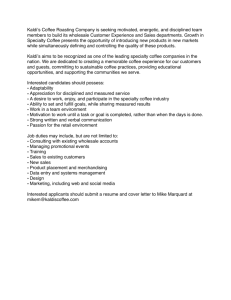

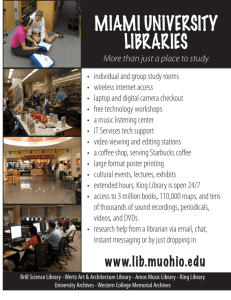

advertisement