The ABCs of Innovation

advertisement

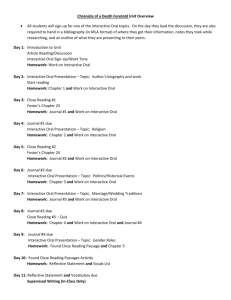

Reflective Thinking Skills Outline What is Reflective Thinking? Reflective Thinking and Managerial Decision Making How to become a Reflective Thinker? Perspectives on Reflection Three stages of Intellectual development MIS 101 Reflective Thinking Dimensions Exercises What is Reflective Thinking? “…the process of creating and clarifying the meaning of experience (past or present) in terms of self (self in relation to self and self in relation to the world.)” Boyd & Fales . Reflective Learning: Key to Learning from Experience. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 1983 Reflective thinking is a part of the critical thinking process referring specifically to the processes of analyzing, evaluating, and making judgments about what has happened. Reflective Thinking and Managerial Decision Making • Individuals… “had never before thought about how they reflected. When asked, they were aware that they did reflect, but they had never considered it as something they could control or something they could use as a learning tool.” Boyd & Fales, Reflective Learning: Key to Learning from Experience. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 1983 • Enhancing decision making requires that we learn from our successes and failures and catalog mentally for future retrieval what has occurred and why. Dr. E. Byron Chew & Dr. C. McInnis-Bowers Reflective Thinking Skills: Developing and Accessing this Management Tool How to become a Reflective Thinker? Good reflective thinking is a process where an individual: – determines what information is needed for understanding the issue at hand – accesses and gathers the available information – gathers the opinions of reliable sources in related fields – synthesizes the information and opinions – considers the synthesis from all perspectives and frames of reference – finally, creates some plausible temporary meaning that may be reconsidered and modified as one learns more relevant information and opinions Cynthia Mazow: Learning, Design, and Technology Stamford University Perspectives on Reflection Metacognition Solving Problems in Uncertainty The Philosophical Mind Metacognition Questions surrounding an individual's ability to reflect is at the core of the historical roots of the concept of metacognition (Brown, 1987). Metacognition as an area of inquiry may be divided into three components: – Metacognitive knowledge- the awareness of one's knowledge and cognitive strategies – Metacognitive judgements and monitoring – Control and self-regulation of cognition Through reflection, one becomes aware of one's own knowledge or cognitive strategies; and one cannot monitor or regulate one's own cognitive strategies, if one is not aware of what those strategies are. Researchers interested in the notion of metacognitive knowledge consider the object of reflection-the mind's "operations"-to be cognitive strategies for performing specific tasks. In such cases, the metacognitve individual must have clear, predetermined goals and standards in order to monitor and regulate her cognitive strategies effectively. Solving Problems in Uncertainty John Dewey and King and Kitchener-propose that individuals engage in reflection when they encounter problems with uncertain answerswhen no authority figure has an answer, when they believe no one answer is correct, and when the solution cannot be derived by formal logic. The uncertainty or the belief in uncertainty is the essential requirement in this case for reflective thinking to occur. An individual must acknowledge that some problems may not be solved by one absolute truth. According to King and Kitchener “ … Reflective thinking requires the continual evaluation of beliefs, assumptions, and hypotheses against existing data and against other plausible interpretations of the data. The resulting judgements are offered as reasonable integrations or syntheses of opposing points of view”. King and Kitchener developed a Model of Reflective Judgement in which the reflective thinker examines and evaluates the available relevant information and opinions to construct a plausible solution to a problem. This plausible solution becomes the individual's belief that is subject to change as one gathers more information. The object of reflection in this situation-the "state of one's own mind"-is recognized as temporary and subject to change. The Philosophical Mind Richard Paul compares reflective thinking to the philosophical mind. In his view, the philosophical mind: – Routinely probes the foundations of its own thought, realizes that its thinking is defined by basic concepts, aims, assumptions, and values – Gives serious consideration to alternative and competing concepts, aims, assumptions, and values – Enters empathetically into thinking fundamentally different from its own, and does not confuse its thinking with reality – Gains foundational self-command, and is comfortable when problems cross disciplines, domains, and frameworks – Habitually probes the basic principles and concepts that lie behind standard methods, rules, and procedures – Recognizes the need to refine and improve the systems, concepts, and methods it uses and does not simply conform to them – Deeply values gaining command over its own fundamental modes of thinking Three stages of intellectual development Dualism. Very young or unsophisticated thinkers tend to see the world in polar terms: black and white, good and bad, and so on. These students also have what Perry calls a “cognitive egocentrism”—that is, they find it difficult to entertain points of view other than the ones they themselves embrace. If they have no strong beliefs on a topic, they tend to ally themselves absolutely to whatever authority they find appealing. At this stage in their development, students believe that there is a “right” side, and they want to be on it. They believe that their arguments are undermined by the consideration of other points of view. Relativism. As students progress in their academic careers, they come to understand that there often is no single right answer to a problem, and that some questions have no answers. Students who enter the stage of relativism are beginning to contextualize knowledge and to understand the complexities of any intellectual position. However, the phase of relativism has some pitfalls—among them that students in this phase sometimes give themselves over to a kind of skepticism. For the young relativist, if there is no Truth, then every opinion is as good as another. At its worst, relativism leads students to believe that opinion is attached to nothing but the person who has it, and that evidence, logic, and clarity have little to do with an argument’s value. Reflectivism. If students are properly led through the phase of relativism, they will eventually come to see that indeed, some opinions are better than others. They will begin to be interested in what makes one argument better than another. Is it well reasoned? Well supported? Balanced? Sufficiently complex? When students learn to evaluate the points of view of others, they will begin to evaluate their own. In the end, they will be able to commit themselves to a point of view that is objective, well reasoned, sophisticated—one that, in short, meets all the requirements of an academic argument. William Perry’s Forms of Intellectual and Ethical Development in the College Years: A Scheme (1970) MIS 101 Reflective Thinking Dimensions The most complete listing of reflective skills is found in Weast (1996) and were arragned and modified in a way to help us reflect: Identify the reasons and the evidence – – – – – – – – Identify the author's conclusion Identify vague and ambiguous language Identify value assumptions and value conflicts Identify descriptive assumptions Evaluate statistical reasoning Evaluate sampling and measurements Identify omitted information Gathers available information of reliable sources Evaluate logical reasoning – Synthesizes the information and opinions from all perspectives and fremes of reference Makes appropriate judgements – Articulate one's own values in thoughtful, fair-minded way (objective, well balanced, and suffient complex) Exercise #1 Describe a situation on-the-job when you were embarrassed, felt awkward, or were otherwise uncomfortable. How do you explain the situation? Your role? The role of others? What key insights did you learn that will assist you in the future? Exercise #2 (Based on the Reflections Guide in Page 219a) Explain in your own words why an organization might choose to change its processes to fit the standard blueprint. What advantages does it accrue by doing so. Explain how competitive pressures among software vendors will cause the ERP solutions to become commodities. What does that mean for the software industry? If two businesses use exactly the same processes and exactly the same software, can they be different in any way at all? Explain why or why not. In theory, such standardization might be possible, but worldwide there are so many different models, cultures, people, values, and competitive pressures, can any two businesses even be exactly the same? Exercise #3 Write 3 things you want your family and friends to remember you by. Write your own epitaph. Famous epitaphs: – I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free.(translated) - (Nikos Kazantzakis) – Go tell the Spartans, stranger passing by that here, obedient to their law, we lie. —Simonides's epigram at Thermopylae Why did I ask you these 2 questions?