Document

advertisement

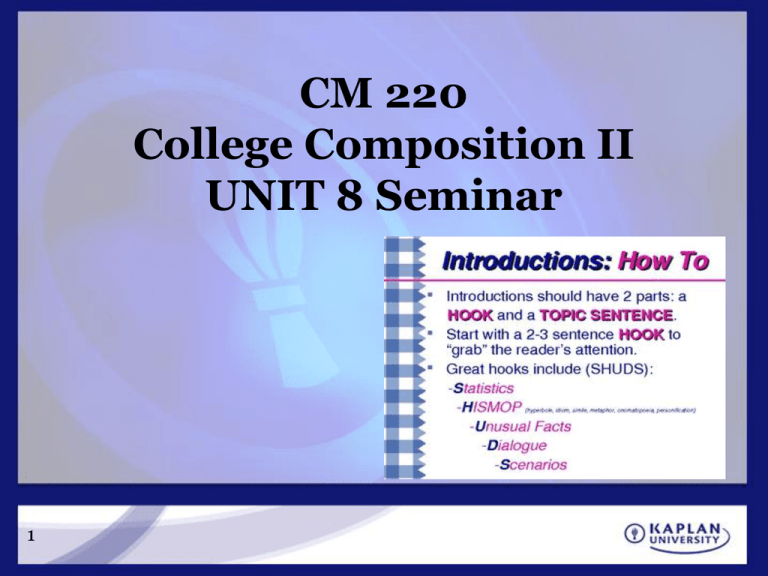

CM 220 College Composition II UNIT 8 Seminar 1 Unit 8 Learning Activities • Reading: Introduction to Unit, The Kaplan Guide to Successful Writing, ch. 14 (pp. 181-194), ch. 15, ch. 16; Roger Ebert’s article • Invention Lab: Post introduction and conclusion and offer classmates recommendations for revision • Seminar: Discuss introductions, conclusions, and coherence strategies that will help students revise for the final project 2 Introductions • Either motivate the reader to continue to read what is written or cause the reader to stop reading. • Can hook the reader. • Can provide a positive first impression of you the writer and your ideas. • Are most effective when they are YOU-CENTERED. They should clearly establish why the information is valuable to the audience? ALWAYS think about the strategies that YOU like. What introductions and conclusions work best to motivate you to begin to read and continue to read? What do your favorite authors do? 3 More tips about Introductions Don’t assume you have to write the introduction before you write the rest of your essay. You can come back to the introduction at any point in the writing process. Forcing an introduction may make it awkward and may create writer’s block. Avoid apologies, obvious statements, trite phrases, and awkward statements like “In this paper, I will…” unless the writing situation calls for it. 4 Strategies for Introductions Establishing the Topic • The introduction is a great place to give any necessary background or historical information, or to define unfamiliar terms. "Grammar" or syntax (the linguistic term) is the study of the patterns and regularities of language at the word-to-sentence-level. Its history can be traced back to the Greeks, 2000 years ago, through the Romans, and extends to present day. Importantly, grammar does not limit itself to what people say is grammatical. True grammar reflects the patterns that real speakers and writers actually use, including, even, their use of the word “ain’t.” • This introduction gives a historical background, but it presents it in an interesting way. 5 Introductions Begin with a quotation: • Make sure to explain its relevance! A quotation with no explanation is not effective at all. The following is an example. "If I commit suicide, it will not be to destroy myself but to put myself back together again." (Antonin Artaud, 1925, p.37) It may sound strange to think of suicide as anything but self-destructive, but to many who have contemplated or committed suicide, as Artaud did, the notion that suicide will somehow heal them or put them back together is quite common. Obviously, suicide is selfdestruction, but to prevent suicide, one must first understand what those who are suicidal feel it will fix. Only then can another path to putting oneself "back together again" be realistically offered. 6 Introductions Begin with a definition: • The key to using a definition is to make sure you are defining something that needs defining. Do not throw in a definition that everyone knows. Euthanasia is “the act or practice of ending the life of an individual suffering from a terminal illness or an incurable condition, as by lethal injection or the suspension of extraordinary medical treatment” (American Heritage Dictionary, 4th edition, 2000). While everyone can agree on what it is, there are deep divides over whether or not it is moral or ethical. • Now consider this definition: Euthanasia is the act of ending a terminally ill person’s life mercifully. It allows people to control their own destiny by controlling their own death. • This second one is interesting because it is a definition that we would not find in a dictionary. It is a stipulative definition...part of the author's job is to support this definition of euthanasia. Why do you think the author gave this definition of euthanasia rather than a dictionary definition? Well, what is euthanasia considered in the legal world (in most of the U.S.)? Suicide or murder, at this point. Just looking at this definition, what do you think the author's stance on euthanasia will be? Note how the persuasion starts early. This definition sets up the paper's argument. The author wants you to see it in a positive way, and part of the author's job is to support this definition of euthanasia. 7 Introductions Begin with a question: Echo, shampoo, window, balcony, hurricane, cruise, noodle, whiskey—these are all good English words, aren't they? Actually, they are now, but they are only a few of the tens of thousands of words that English has borrowed from other languages. In fact, English has borrowed and generated so many words that it has the largest vocabulary of any language on the planet. Just how many words it has cannot be determined—are “care,” “careless,” and “carelessness” to be counted as one word or three? The range, however, is from 500,000 (the number of entries in the Oxford English Dictionary) to well over a million. To be fair, no individual English speaker has a vocabulary of this size—depending on education and other factors, an individual’s range is usually between 15,000 and 70,000 words—yet it remains fascinating that English has gained most of its words by borrowing them from other languages. But avoid a question that is obvious and leads nowhere. 8 Introductions Begin with a narrative: • If you begin with a very short narrative or story that relates directly to your paper, be sure it is short, to the point, and relevant to your topic. Sandra sat down on the coach and took a deep breath. She slowly put on her shoes, stood up, and reached for her purse. As she walked to the front door, her pulse grew rapid and she felt short of breath. She started to tremble. As her hand rested on the doorknob, a wave of panic washed over her. “I just can’t do it,” she thought. She stepped back from the door, defeated once again. Sandra, like thousands of other Americans, suffers from agoraphobia, an overwhelming and unnatural fear of being in public. • You can use this method to "frame" a paper—start the story in the introduction and end it in the conclusion. 9 Introductions Begin with an interesting fact or startling information: • This information must be true and verifiable, and it does not need to be totally new to your readers. It could simply be a pertinent fact that explicitly illustrates the point you wish to make: Water conservation usually focuses on shortening the length of showers or reducing lawn watering, but according to the Worldwatch Institute’s senior researcher Alan Durning (1988), over half the water used in the United States is devoted to meat production. 10 YOUR TURN Share your introduction with the class. What are your concerns about this introduction? Class, offer advice for strengthening this introduction. What strategy would be most likely to HOOK you and motivate you to read this paper? 11 Conclusions Should not simply repeat the introduction or restate the facts. That may insult the audience, unless the paper is lengthy and particularly complex. In some writing situations, however, a conclusion can restate the facts. They are the last thing your audience reads. Leave a lasting and good final impression. 12 Some Strategies for Conclusions Mirror or complete the introduction: • Recall the narrative introduction about Sandra, the agoraphobic woman who was too afraid to leave her own home? When the introduction left off, she was backing away from the front door, unable to work up the courage to go out. The conclusion could revisit Sandra after she has received treatment. It could show how much happier she is with this phobia behind her. 13 Conclusions Challenge the audience to take action from what they have learned: • In this case, the author has written a paper on poor parental conduct at their children’s sporting events and the effect this has on children. In the conclusion, she puts the responsibility on the audience by suggesting parents need to take responsibility for their own behavior and make youth sports positive again: Parents across the United States need to let go of their own agendas, and athletic associations need to enforce parental and coaching codes of conduct through classes and training. As a result, the world of youth sports can be returned to the children where they can all learn to enjoy a sport, learn the skills of a sport, play, and most of all have fun. 14 Conclusions Bring up remaining questions: • 15 There are several ways to use this technique. You can suggest answers to the questions or you can propose further research that would answer those questions. You can also use this technique to minimize the importance of questions that may be lingering in the minds of your audience. The following conclusion uses questions to accomplish this: With the rising price of, growing demand for, and lessening supply of gasoline, is the only solution to reinvent the automobile? Is the next new technology just around the corner, ready to solve this problem? While new technologies will shape the future, and while the current automobile is likely to become obsolete in the decades to come, there is a great deal we can do today far short of abandoning our cars. We can buy more fuel-efficient vehicles. When we buy a home or rent an apartment, we can try to find one within walking distance to a grocery store. We can carpool to work or take public transportation. We can even talk to our employers about setting up a staggered work schedule: cars burn the most gasoline and create the most pollution when driving in heavy traffic. Workers who are allowed to start work two hours earlier or two hours later to avoid rush-hour congestion can save gasoline. Regardless of what we do now, or what innovation brings, conserving gasoline now makes sense. YOUR TURN Now, share the draft of your conclusion. What are your concerns about your conclusion? Class, offer advice for strengthening your classmates’ conclusions. How would you honestly respond to this conclusion and what other strategy might work better and why? 16 More help… For an excellent Writing Center Workshop on introductions and conclusions, review the following: http://khe2.acrobat.com/p44415570/?launcher=fa lse&fcsContent=true&pbMode=normal 17 Keys to successful peer review 1. Open, honest critique: you should not be mean or rude, but you should constructively assess your peer's work (telling someone "I wouldn't change a thing" gives them no ideas, and therefore is no help) 2. Timeliness: emailing your draft to your peer partner to review and reviewing their draft on time! A critique sent to someone a week after the paper was turned in for a grade is not helpful. Receiving Advice • Identify potential problem areas and ask for specific help with them. • Try not to get defensive. Understand that the reader is offering honest help, not personal criticism. • Provide a true draft, not a jumble of brainstorming ideas or planning notes. • Take notes, wording the advice in a manner that works for you so that you will know exactly what to do later when you sit down to revise. Giving Advice • Begin with the positive. • Deal with big questions first, like the thesis statement and organization. • Be specific. Vague phrases like "This is good" are not helpful. Explain why and how it is good, such as "I like the way you emphasized your main point with that example." • Be honest. You are not helping the writer if you avoid mentioning a problem. • Word criticism carefully by focusing on what you are thinking when you read a passage. For example, say "I don’t understand exactly what you mean by..." rather than "This makes no sense," or "My mind tended to wander at the beginning" rather than "Your introduction is boring." Such wording is less threatening than a direct criticism. • Follow the golden rule of responding to others' work as you would want them to respond to yours. • Don't try to be the teacher. Your job in a peer group is not to evaluate or grade the work as a teacher would, but to respond to it. Questions to ask yourself when doing a peer review: • What do you like about the paper? What don't you like? • What do you find especially interesting? • Where is the paper especially clear about what it is trying to say? • Where are you confused? • Is there any passage that seems to get away from the main point of the paper? • Where does the paper move smoothly from point to point? Where does it make an abrupt shift? • Is the thesis statement clear and complete? • Is the order of the paragraphs effective? • Does the paper come to a satisfying conclusion? Types of comments or responses to provide: Pointing: Say which ideas (or words) stood out. For example: "In paragraph 1 where you described Miss Bessie, you describe her as being five feet tall and weighing less than 100 pounds, but also as 'a towering presence in the classroom.' That really caught my attention and gave me a picture of a tough little lady." Or "Your description of the "bad situation" in paragraph 4 didn’t give me a clear picture of why it was bad. Could you describe it more clearly? Why is it bad?“ Summarizing: Explain the writer's main idea (purpose) in a single sentence. "I really understood your main idea of the importance of beginning saving money for the future at a young age." Or "Your example of...really made the point clear." Or "I wasn't sure what point you were trying to make - could you possibly reword the last sentence (or third sentence or whichever one) so that the point you are making is clearer or more easily understood.“ Telling: Tell what happened to you as you read the paper. Example: "When I got to the third paragraph, I was confused because..." or "I agreed with the point you made at the end and wondered if...“ Showing: Use specifics if any of these apply. Describe the writing as if you were describing voices (Was the tone of the essay shouting, whining, lecturing). The evolution of the writing: where it came from and where it seems to be heading. Intention: what was the actual intention, and what might have been a crazy intention Jabbering: did the writer go on and on and say nothing? Unit 8 Invention Lab • • 23 After reviewing this unit’s reading on introductions and conclusions, create new opening and closing paragraphs for your project. Then, write a paragraph describing what approaches you selected, what changes you made to the paragraphs in your draft, and why you think the new paragraphs will make an effective frame for your essay. Your post should be at least 300 words, and be sure to include your revised introduction and conclusion paragraphs. Respond to two classmates’ posts. Please begin by reviewing a post that has not yet gotten a response. You need to offer specific suggestions for improving and revising their paragraphs. See the guidelines below for issues to consider in your response, and keep Roger Ebert’s recommendations about effective film reviewing in mind. You don’t just want to state what you like or do not like about the paragraphs—explain why you feel the way you do and provide evidence to support your assertions and offer suggestions for improvement. Guidelines for constructive critique: Reading and responding to each other’s work is a rare and wonderful experience. Though you may find such work (the reading and responding as well as the sharing) frightening at first, writers need input—they need to test their work on a real audience and then evaluate the feedback and make appropriate plans for revision. The best tool a writer can have is a friend who will read and respond critically and tactfully to drafts. Indeed, writers need other writers to help them discover what it is they have to say in a piece of writing and then to articulate that meaning as effectively as possible. When responding to a peer, exercise tact and be specific in what you say. Take your time and develop your thoughts so that you can help out a fellow writer. Please do not focus on or mark GUM (grammar, usage, and mechanics) issues. Do not comment on spelling. A work in progress is not about correctness; it’s about finding the inherent truth in a piece of writing and uttering it. Your job as a reader and responder is to comment on substantive issues of content and meaning, and thus offering the kind of feedback that writers need to discover what it is they have to say. 24 Providing critique What to do: • • • • • • 25 Highlight any word, phrase, sentence, or passage where you feel the language is particularly strong and the point especially compelling. What is the writer doing? Let the writer know your reaction to this content. Consider the discussion of style and voice in Ch. 15 of The Kaplan Guide to Successful Writing as you develop your response to this question. Highlight any word, phrase, sentence, or passage where you feel the writing needs more work. If a word seems off, mark it. If a sentence is clunky, mark it. If you are confused by some content or an example seems flat, let the writer know. Do the paragraphs show an awareness of audience and purpose? That is, does the writer take into consideration that the purpose of the paper is to persuade which means the audience will largely not share the writer’s view on the issue? Where is the persuasion effective and where does it need more work? What is one strength of each paragraph? Why is what you identify a strength? What is one aspect of each paragraph that needs improvement? Why does what you identify need to be improved upon? What lingering questions do you have about these paragraphs or your classmate’s “big idea” in general?