The Hunger Games - Not Entirely Stable

advertisement

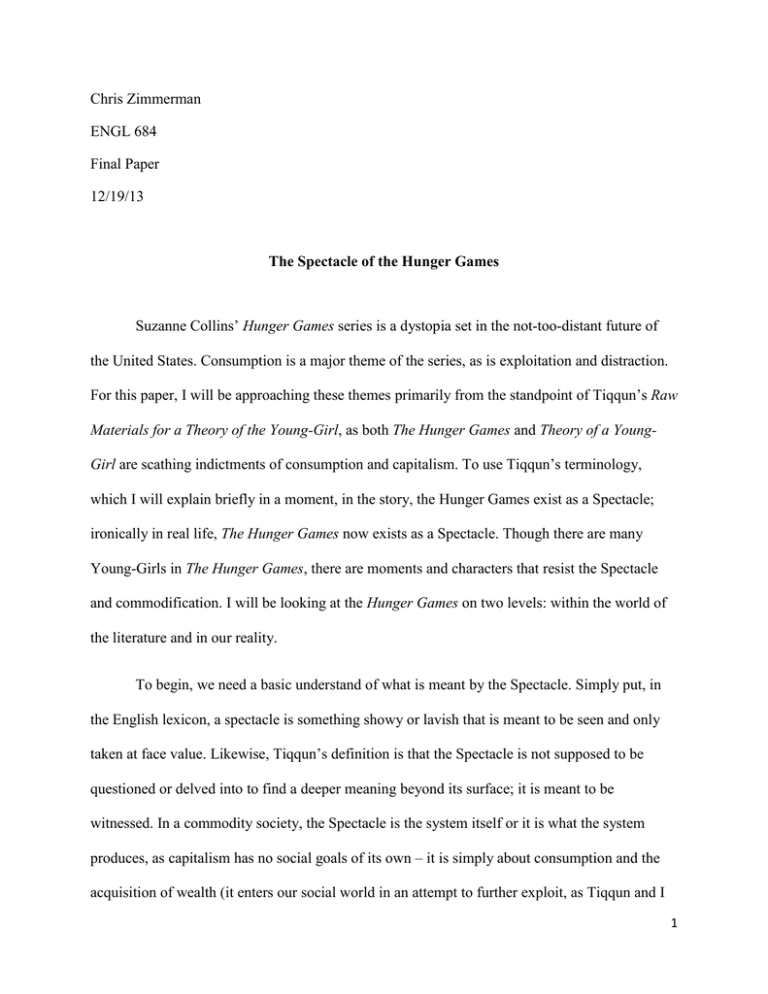

Chris Zimmerman ENGL 684 Final Paper 12/19/13 The Spectacle of the Hunger Games Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games series is a dystopia set in the not-too-distant future of the United States. Consumption is a major theme of the series, as is exploitation and distraction. For this paper, I will be approaching these themes primarily from the standpoint of Tiqqun’s Raw Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl, as both The Hunger Games and Theory of a YoungGirl are scathing indictments of consumption and capitalism. To use Tiqqun’s terminology, which I will explain briefly in a moment, in the story, the Hunger Games exist as a Spectacle; ironically in real life, The Hunger Games now exists as a Spectacle. Though there are many Young-Girls in The Hunger Games, there are moments and characters that resist the Spectacle and commodification. I will be looking at the Hunger Games on two levels: within the world of the literature and in our reality. To begin, we need a basic understand of what is meant by the Spectacle. Simply put, in the English lexicon, a spectacle is something showy or lavish that is meant to be seen and only taken at face value. Likewise, Tiqqun’s definition is that the Spectacle is not supposed to be questioned or delved into to find a deeper meaning beyond its surface; it is meant to be witnessed. In a commodity society, the Spectacle is the system itself or it is what the system produces, as capitalism has no social goals of its own – it is simply about consumption and the acquisition of wealth (it enters our social world in an attempt to further exploit, as Tiqqun and I 1 will bring up later, but it does not have social aims per se). The Spectacle can exist simultaneously as an individual occurrence, such as a gaudy performance of a boy band, and as the larger Spectacle (and the system itself) as a whole, since the Spectacle is like a hall of mirrors. In that sense, each instance is part of the larger problem. Tiqqun adds, “The whole world of the Spectacle is a mirror that reflects to the Young-Girl the assimilable image of its ideal” (28). But the Spectacle cannot exist without Young-Girls, which is actually a non-gendered term Tiqqun uses at great length to describe larger-than-life as well as average citizens in a capitalist society. As Tiqqun phrases it, “the Young-Girl is…the model citizen such as commodity society has defined it…” (iii). Put another way, the system defines (rarely overtly, however) how the citizens should conform and act, be it Panem, United States, or another capitalist country. Tiqqun says, “The Young-Girl is good for nothing but consuming; leisure or work, it makes no difference” (2). Put plainly, the Young-Girl is the ideal conforming consumer in a capitalist society. The Young-Girl also seeks to commodify all that she sees and “is an engine for reducing everything that comes into contact with her into a Young-Girl” (Tiqqun 27). Before we delve too far into the Spectacle and its adoring Young-Girls, we must look at the economic and political situation of The Hunger Games before we can discuss how they relate to Tiqqun’s book and the capitalist society of the U.S. today. The Hunger Games takes place in a post-apocalyptic North America, now called Panem. Even though some sort of attempted revolution against the capitalist system and ensuing fallout of an apocalypse occurred, capitalism is still alive and well in North America. In fact, it thrives as the continent looks like a mix of a near-future capitalist society mixed with a society from the glory days of capitalism, the early 20th and 19th centuries, judging on how people are dressed and the jobs they hold in the districts. 2 There is a vast disparity of wealth between the Capitol and the outlying districts. This is an interesting contrasting of the utopian Capitol which has all the trimmings of a decadent society and looks like it is not set in a post-apocalyptic setting against the dystopian, impoverished districts. Panem is made up of twelve districts run by the Capitol. Each district specializes in producing goods or raw materials that they provide to Capitol. District 12, where the heroine, Katniss Everdeen hails from, produces coal, for instance. The other districts produce luxury items, lumber, agriculture, power, etc. that the Capitol exploits or appropriates from them. District 2 even literally supplies people to serve as Peacekeepers, the police force/army of the Capitol who enforce the Capitol’s plutocratic laws. It is interesting to find that the name of the new continent “Panem” is derived from the Latin phrase panem et circenses, which literally translates into “bread and circuses”. What this means is that the populace can be distracted by the ruling political institution if they are simply given enough food and entertainment to keep them from becoming engaged in politics or fighting for more rights or power. This is perfectly fitting with the setting of The Hunger Games because the citizens of Panem are distracted from opposing the government and trying to better their abysmal working conditions by having the celebration of the gladiatorial Hunger Games to watch. The Hunger Games themselves would be considered a spectacle, or something that is meant to be seen but has no further depth or anything behind it; just more and more Spectacle behind the curtain. As such spectacles, the Hunger Games are meant to be seen and enjoyed by the viewers without looking behind the games themselves and seeing the contestants, or tributes as they are called, for the people that they are and the impoverished places that they come from. In a sense, the games themselves are consumed by the audience. Pushing that idea further, the 3 tributes’ bodies (and labor) are therefore consumed (in some cases quite literally) in these contests, as there is only supposed to be one survivor. Although a vast minority of the population of all of Panem, at only 96,463, the Capitol consumes the vast majority of the resources (The Capitol). While the Capitol progresses and gains better technologies and living conditions for its citizens, the rest of the population of the continent regresses. The Capitol’s domination of the districts is so harsh and repressive the economies of the districts appear to have reverted back to a barter system with no known currency (or so little currency that we do not even see it), as we witness Katniss trading for some string early in the first movie. Other times, we hear the characters talk about trading squirrels for other food or goods. Meanwhile, citizens of the Capitol live posh lifestyles, apparently working little or not at all and spend their days dressing in the latest fashions and going to parties, as these people are the owners of the means of production and the exploited labor. These capitalists appear to have nothing to do but consume. For them, life is only about being Young-Girls and partaking in the Spectacle. Young-Girls exist because the Spectacle has created them and they in turn perpetuate the Spectacle (and the system) in a seemingly unending cycle. In the first movie, the 74th annual Hunger Games is taking place; the Spectacle of these games keeps the people complacent as Young-Girls for generations. We do not know much about the rebellion against the capitalist regime of the near-future of the United States, but we do know the resistance was brutally put down. In the opening credits of The Hunger Games, we are told that “In penance for their uprising, each district shall offer up a male and a female between the ages of 12 and 18 at a public ‘reaping.’ These tributes shall be delivered to the custody of the Capitol and then transferred to a public arena…. Henceforth and forevermore this pageant shall be known as The 4 Hunger Games.” First of all, “pageant” is a perfect synonym for spectacle as it is a viewing event that is meant to be consumed and where beauty is only skin deep. Secondly, the old rebellion itself has been commodified. As Tiqqun puts it, “The Young-Girl privatizes everything she perceives. Thus, for her, a philosopher is not a philosopher, but an extravagant erotic object; in the same way, for her, a revolutionary is not a revolutionary, but a piece of jewelry” (55). The Spectacle of Panem has taken these revolutionaries and turned their struggle and their deaths into a pageant. Young-Girls do not question the Spectacle or look for meaning in their lives or others or in the Spectacle itself. The Spectacle simply is. The Hunger Games is filled with Young-Girls. The Capitol has the greatest abundance, as their city has wealth beyond the dreams of the other districts. They consume commercial goods and food the rest of populace can only catch glimpses of. They want to consume so much food that even when they are full they want to keep eating, so they drink something that will make them throw up so they can continue to eat and be happy. Meanwhile, people in the districts starve. In fact, food appears to be one of the only commodities we see in the outlying districts, as it is a scarcity that everyone trades for. People can even trade to have their names entered more times into the Hunger Games drawings in exchange for more food. This food commodity comes at a high price, too high of a price, as Katniss warns her sister, Primrose. The Young-Girl loves fashion because it is all about appearances and what is on the surface, like the Spectacle. And there if there is one character in the movie that is synonymous with fashion, it is Effie Trinket. Even her name is Young-Girl. A trinket is “a small or worthless ornament or piece of jewelry,” which is an interesting contrast against the mockingjay pin that becomes a symbol of resistance against the dominant system (The Free Dictionary). From the moment we first see Effie, she is wearing outlandish clothes that in themselves are sort of a 5 spectacle; flashy does not even begin to describe her style. Being a Young-Girl, aesthetics are more important than utility, so Effie is only seen in heels, footwear known to be painful, flashy, difficult to walk in, but aesthetically pleasing. Effie’s face is covered in makeup, which hides her face in one sense and is the face of a Young-Girl in another sense, as the makeup is the face of her identity. Effie is also entirely concerned with appearances when she goes out in public with her tributes. She is afraid of being embarrassed by their behavior in front of others, even though the tributes will likely be facing their own deaths soon, that is less important than looking good and acting proper in front of the cameras. Her need to clothe herself in the finest fashions and makeup and her concerns with etiquette can be seen as Tiqqun’s entry that speaks to the YoungGirl’s “…maniacal effort to attain, in appearance, that definitive impermeability to time and space, to her surroundings and history, her effort to be impeccable everywhere and at all times” (17). Another glowing example of a Young-Girl in the Capitol is Master of Ceremonies, Caesar Flickerman. Clearly, like Effie, he is concerned with the latest fashions in the Capitol, not only with his own wardrobe and his appearance, but during his Spectacle-produced show (certainly a spectacle on its own, as the tributes are all dressed up like contestants of the Miss America Pageant), he comments on the tributes’ outfits. But, for him it goes far beyond fashion. This character is the absolute embodiment of the Spectacle and Young-Girls in The Hunger Games. Not only does his show distract the masses of the Capitol and the districts, he is an announcer during the Games. He is literally the mouthpiece of the Spectacle in The Hunger Games. Tiqqun says “the Young-Girl doesn’t speak; on the contrary: she is spoken—by the Spectacle” (9). Caesar’s voice, with its ability to entertain and its transparently false sense of concern, serves only bring the Spectacle to the citizens of Panem. His job is to sell the Hunger 6 Games. When some of the tributes of the 75th Hunger Games hint (or in Johanna Mason’s case, yell a string of curse words) about the unfairness of the quarter quell since victors were supposed to be free from future reapings, Caesar does not actually respond to them and their ideas, he merely keeps playing to the audience and using his showmanship to keep selling the product of the show. The Young-Girl neither likes nor understands nonconformity. At the end of Caesar’s show in Catching Fire, the tributes hold and raise their hands in a show of solidarity and rebellion. Caesar does not tolerate this nonconformity so he has the cameras stop broadcasting. Caesar’s show and the Hunger Games satisfy, create, and perpetuate Young-Girls because both his show and the Games are designed to be sold and consumed. The Hunger Games not only generate excitement in the Capitol crowd, but it gets them to throw lavish parties and consume even more goods, similar to the rampant consumerism we see during the holiday season. Every step of the way during the tributes’ training and interviews, the Gamemakers generate grades on the tributes and display the odds of victory to the public, who can then gamble on outcome of the games. Well-to-do citizens can pay a small fortune and have items sent to their favorite tributes in the Hunger Games. And how do tributes earn favor? By “getting people to like [them],” as Kat and Peeta’s mentor Haymitch puts it – by selling themselves to the spectacle and embracing the parades and the pageantry, by going on Caesar’s show and becoming part of the spectacle. Peeta seems exceptionally good at this, waving to the fans and having Katniss hold his hand since the crowd “will love it!” to help sell the idea that they are lovers. Is he doing it to win them favor and keep them alive or does he enjoy whoring himself out to the Spectacle? Most likely it is the former, but as a result of his actions, the Young-Girls gobble it up and it helps the Spectacle become more bloated. Even love is not sacred and can be commodified. Haymitch tells his tributes, “I can sell the star-crossed lovers” to 7 which Katniss objects to at first. “It’s a television show. Being in love with that boy might just get you sponsors, which could save your damn life,” he adds. Katniss comes around to the idea and plays along before, during, and after the Hunger Games. During the Victory Tour that Katniss and Peeta went on, the selling of the love story continues. Though Katniss and Peeta have defeated the Spectacle for a moment at the end of the first movie, the Spectacle quickly assimilates their story and commodifies it to the people of Panem. So well does it commodify the love story, it ensnares Peeta and Katniss in it, requiring them to act out for the cameras in the beginning of the second film. As the film goes on, they keep playing to the story, adding the idea of a wedding between the two “lovers.” Immediately, the Spectacle looks to sell this. The Hunger Games Gamemakers could not ask for anything better to help market the show than the idea of the star-crossed lovers, as the crowd eats it all up. These Gamemakers control, produce, and promote the games. The bottom line is that boring games do not sell. Their job is to make sure the crowd is entertained. Perhaps they release genetically modified animals to spice things up or send a tidal wave or poison gas at sleeping tributes to keep the crowd watching. Sleeping is not fun to watch, after all, but people running in fear for their lives from poison gas? That’s exciting. That’s pure spectacle. The Commodity of the Hunger Games is so important that lackluster games risk the life of the head Gamemaker (The Hunger Games Wiki). In a previous Hunger Games, a tribute named Titus turned to cannibalism, eating the other tributes after he killed them. “Cannibalism did not go well with the Capitol audience, as the Gamemakers had to censor most of his kills” (The Hunger Games Wiki). One can imagine how difficult it would be to commodify cannibalism, which is why it shows how it shows that there can be an outside to the Spectacle of the Hunger Games. “He was eventually killed in an avalanche, which was thought to have been set up by the Gamemakers, to 8 ensure that the victor was not a lunatic” (The Hunger Games Wiki). They have to be sure that their victor is saleable. One can imagine all the Young-Girls trailing behind these spectacular games, selling all sorts of merchandise to the wealthy citizens of the Capitol, but the Spectacle cannot sell the Hunger Games the same way to the districts as it can in a more traditional capitalist way to the Capitol because the districts are impoverished and may not even use currency. The Spectacle needs to commodify these games to the districts by selling it to them as hope. Hope, in one sense, is that things will never be as bleak as they were before just prior to the start of the Hunger Games, according to the propaganda film everyone is forced to watch every year at the reaping. In the film, President Snow says, “Freedom has a cost.” That is an interesting choice of words, in light of the Young-Girl commodifying everything. Snow’s narration in the film also stresses the honor of representing the district and the potential rewards. If the chosen tribute of the district comes home a victor, he or she will be rewarded with better housing, food, and wealth. All of these would be desirable to people living in such squalid conditions, hoping for their lives to be better. In a conversation with Seneca, the Head Gamemaker of the 74th Hunger Games, President Snow asks him, “Why do you think we have a winner?” Seneca has no response. “I mean, if we just wanted to intimidate the districts, why not round up twenty-four at random and execute them all at once? It would be a lot faster,” Snow continues. “Hope. It is the only thing stronger than fear. A little hope is effective. A lot of hope is dangerous.” Not only does the Capitol make the Games, it appears to even set the exact price on the commodity of hope. There is some hope that the Young-Girl cannot commodify everything and everyone. And not everyone that lives in Panem is a Young-Girl. Katniss might spring to mind as the foremost leading example of a non-Young-Girl, and in a lot of ways, that is true. Obviously, she 9 eventually becomes synonymous with the image of the mockingjay and resistance, but for now let us look a little closer at her as a person and not an idea. One of her greatest non-Young-Girl moments is when she volunteers out of love for her sister and wants to go in her place to the Hunger Games. The act of volunteerism is not easy for the Young-Girl to commodify since giving freely is contrary to selling. Tiqqun says, “The Young-Girl is an absolute: she is purchased because she has value, she has value because she is purchased” (31). By that logic, in the Young-Girl’s mind, something that is given freely must be not have value. Even Katniss can be bought and sold. During the Victory Tour that she and Peeta went on following their survival in the Hunger Games, she allowed the Spectacle to parade her around (quite literally) to the districts, helping to sell the idea of the Hunger Games and its message of complacency and controlled hope. During one of the days of the tour an elderly black man from District 11 decided to make the hand gesture of the District 12 sign, which Peeta and Katniss and people from the crowd all joined. This solidarity was put down by having a Peacekeeper execute the man in front of the crowd. After that, Katniss and Peeta were forced to read from cards for their future speeches and stick only to the cards. Despite witnessing that horror and other crowds thirsting for help in resistance, they dutifully read the prepared speeches and continued to sell the Spectacle. The series sets up Katniss Everdeen as the heroine, but other characters are just as heroic and some even resist the Spectacle more than she does. Through Tiqqun’s criteria, other characters are not as Young-Girlish as Katniss since they are less willing to conform and are willing to die for their beliefs instead of selling out; Kat will let herself be paraded around and play along with the game, like most of the other tributes/victors that we see, with one glaring exception – Johanna Mason. When she was on Caesar’s show, she refused to play along with the 10 interviewer and his spectacle by replying to one of his questions by saying sarcastically, “Whole country in rebellion? Wouldn't want anything like that!” (Hunger Games Wiki). Later in the conversation she said exactly how she felt about the Hunger Games in a stream of curse words. After the interview, when she was talking with Haymitch, Katniss, and Peeta in the elevator, she expressed how much she despised her costume and the pageantry by stripping off all of the clothes in disgust. To have to conform even slightly with the spectacle of the show was difficult for her to accept. Her fiery attitude and lack of respect for the Games and their audience may have put her life in jeopardy because it is doubtful the spectators would be likely to donate money to send supplies to her during the Games. Another victor/tribute of the 75th Hunger Games that defies commodification is Mags, the elderly woman in her eighties that volunteers in place of another woman. As we find out in the end of Catching Fire, the tributes Mags, Johanna, Peeta, Beetee, Wiress, and Finnick were all involved with a plot formed with the help of Haymitch and Plutarch (the new Head Gamemaker who secretly opposes the Capitol) to get Katniss out of the arena alive at any cost. As Haymitch puts it, half of the contestants were in on the plan. This willingness by the contestants to selfsacrifice for a cause is difficult for the Young-Girl to commodify. These people were all willing to do whatever it takes, even if they have to lay down their lives to save one person’s – the one person who coincides with the ideas of hope and rebellion. To the people of Panem, Katniss is the mockingjay, the image of rebellion. But first, how did the mockingjay become such a symbol? We first see it in the first movie when the woman in the market gives it to Katniss free of charge in a non-Young-Girl moment, as the act of giving is hard to commodify. Katniss later wears the pin during the Hunger Games. At the end, she defies the Capitol by refusing to kill Peeta and instead plans on 11 committing suicide with Peeta by eating poison berries. Her defiance earns her the respect of the people and she becomes synonymous with the mockingjay. This pin which may have started out as a simple trinket has become much more. In the second film, we see the image of the mockingjay graffiti’d on walls because it has become an idea or symbol of resistance to the people in the districts. And sometimes ideas are moments where we can see something being free from the Spectacle. As Tiqqun would phrase it, these ideas or moments are what make visible what is invisible in Spectacle, and that is the key to resisting the Spectacle. But, the Young-Girl is not so easily defeated. She is an insidious adversary. As Tiqqun puts it, “The Young-Girl has no opinion or position of her own; she takes shelter as quickly as possible in the shadow of whoever wins” (45). In Panem, we see the Young-Girl quickly try to take the image of the mockingjay and commodify it. Katniss’s mockingjay pin “...spawned a new fad, being replicated as a fashion accessory and even used as the basis for tattoos…” for residents of the Capitol who want to wear the symbol, not as a symbol of resistance against the government, but because the victor of the recent Hunger Games wore it (The Hunger Games Wiki). Even though most people in the Capitol appear to be Young-Girls, Cinna is a quite an exception. At first he appears to be a Young-Girl, since after all, he is surrounded by YoungGirls, he is a stylist (a perfect Young-Girl career that emphasizes surface value) and his job is to make the tributes look good for the cameras and help sell the show. Yet despite this all, Cinna is not a Young-Girl. He uses his position to send a message to authoritarian President Snow and to all the people of Panem. He knowingly risks his life by having Katniss’s wedding dress turn into a mockingjay outfit on Caesar’s show. In one move, he has taken the symbol of the commodified wedding dress and turned it into the image of rebellion – the mockingjay. 12 Despite all of the above examples of rebelling against the Spectacle, the one character that seems the most resistant to Young-Girlification and the system is Gale. In the very first conversation he has with Kat in the movie, they talk about selling meat to the Peacekeepers. When he opposes it, Kat says “Like you don’t sell to the Peacekeepers.” He replies, “No! Not today.” This is noteworthy because even though he is desperately poor, he refuses to sell to the Peacekeepers and, thus, the system on the day of the reaping. Symbolically, he is resisting the Spectacle here. As he and Kat talk further, the televised Hunger Games event itself comes up. Gale says, “What if one year everyone just stopped watching?” Kat looks at him incredulously like it is not a possibility. “It won’t happen.” Gale will not give up so easily as Kat, though. He even suggests that they leave the town and go live in the woods. It does not get much less nonYoung-Girl than to want to live completely outside of commodity society (if this is even possible). Gale is so opposed to the consumerism of the Capitol that he refuses to accept a pair of gloves that Katniss gives him upon her return from the Capitol, saying that he does not want anything that was made in the Capitol (The Hunger Games Wiki). In Catching Fire, when the Peacekeepers were sacking the town, Gale could have simply run away, but instead he threw himself into the Peacekeepers who were hurting the people of the town. It must be reiterated that while the locals of the districts work in the forests or in the coal mines, etc., none of these people actually own the means of production and thus have only their labor or their bodies to sell for whatever price the market, or the Capitol, sets. Obviously, this seat of government is not only the center of the political power but also of the economic power of Panem. Is Collins making commentary here by naming the city simply “the Capitol” since it serves as a double meaning with “capital,” showing that the city is the embodiment of money and capitalism in a single city? Perhaps she is even referencing the spirit of Marx’s Das Capital. 13 Does Collins hope that her books will incite an Arab Spring-style uprising here in the United States to bring rights to the workers or a Marx-envisioned worldwide revolution that brings capitalism itself to its knees? Or is she only a Young-Girl herself, looking to commodify the ideas in her books and get rich? The case could be made either way, but that is neither here nor there for the Young-Girl, because she is ever looking to commodify anything she sees and turn everything into her image, no matter if the source is pro-capitalism or anti-capitalism. Peter Travers of Rolling Stone says that Catching Fire is “Spectacular in every sense of the word.” I do not think he realizes just how true that statement is, even if he has no familiarity with Tiqqun’s work. While I am not sure of the exact specifics of the rights to this intellectual property, it is clear that Lionsgate Entertainment, Scholastic Inc., and/or Collins license out the rights to the film and books so that companies make t-shirts, action figures, posters, official Hunger Games subs at Subway, and much, much more that young girls (and boys and adults) can clamor over. One cannot help but notice the irony of a story about worker’s rights and human rights ending up forcing people (including children) in horrible working conditions for little pay to create the textiles for the Hunger Games clothing, etc. Would that make China or Vietnam the equivalent of District 8 (the textiles district)? The movies unintentionally show us the power of the Young-Girl to corrupt everything, to jump from fiction into our reality. The Capital Couture website is a great example of this. This website looks as though it is a website that exists in the county of Panem. It must be noted that the viewer him/herself would be a well-to-do citizen of the Capitol because it appears the other districts do not have such technology. Even the website is “.pn” and not “.com”. It is a website that talks, rather mainly just shows (an important distinction when talking about the Spectacle), about Panem culture and the latest clothing and shoe fashions, makeup, and bizarre technologies 14 available at the Capitol. At first, it appears this is only a mock website with some information about a fictional place, but upon closer inspection, some of these stories and images link to pages where you can buy the fantastical merchandise. The Spectacle is pervasive indeed as it jumps between worlds, seeking to commodify all it sees. The Capital Couture websites and its sister sites encourage the visitors/consumers/Young-Girls of the site to share the information (marketing) on Facebook, Twitter, Google+, etc. In a rather overt way, this shows how the Spectacle seeks to infiltrate and commodify human social experiences. As Tiqqun put this, “capitalism noticed that it couldn’t maintain itself as the exploitation of human labor without also colonizing everything found beyond strictly the sphere of production” (iii). This is not meant strictly social as in expressive, sharing way, but more of in a “creat[ing] its own culture, leisure…” way in an attempt to commodify all aspects of human existence that it can (iii). Other than the stockpiles of merchandise, are the Hunger Games movies a Spectacle in themselves (i.e. – not within the level of the universe of the story, but as a product in our world)? Though we might be able to find moments in the movies that may resist commodification (possibly the base ideas of human rights), it could be argued that the films are perfectly readable (just like the Young-Girl) and that they play to our expectations as to what a movie about dystopian workers’ revolution would look like. They are movies of surface value. The district that we see the most of is District 12, which is stereotypical and completely expected of an industrial revolution-era lookalike place – where miners in overalls are working at the coal mine, not call center telemarketers and part-time fast food workers. And the Capitol? It is exactly what we would expect to see – people with incredibly flamboyant fashions, outlandish makeup, perfectly styled beards, lavish parties, and debauchery as their average day. The president is a cardboard cutout of a ruthless, coldblooded dictator, and the heroes perfectly innocent (and 15 attractive) creatures forced into a situation beyond their control (but rarely, if ever, have to make a difficult choice). There is even a cookie-cutter love triangle to satisfy the “need” for romance in the film. It appears all perfectly legible to us, the viewers or rather, consumers. If the aforementioned cannibal scene appeared on screen with all its visceral gore, that would have been a moment that resisted commodification, or if Katniss and Peeta had committed suicide at the end of the movie, that might have been as well, but as such, neither of these possibilities happened on screen. Also, like the Gamemakers in the movies, the movie makers cannot have their own Hunger Games be boring because that would not sell. In a sense, we are the citizens of the Capitol watching the Hunger Games. The first movie gives us a false hope of seeing something unexpected, something that would de-commodify itself by showing who all the contestants are and entertaining the thought that it might be someone other than the gladiator from District 1 as the villain to defeat at the climax, but it backs down and sells out and gives us precisely that. Just think of how poor ticket sales might be if the Hunger Games came down to Kat vs. Rue. The movie would not dare do the unthinkable and have the hero kill “an innocent little girl” like Rue (who is also stereotypical herself). The Spectacle requires itself and the Young-Girl to be perfectly legible. Even most of the actors themselves appear to Young-Girls, posing for the cameras, agreeing to interviews with Young-Girl interviewers and thus promoting their movie to sell tickets and not talking about the issues of disparity of wealth and global hunger issues that the story brings up. Stepping back and looking in – are we all Young-Girls watching the Spectacle of these films? What role do we play in proliferating the Spectacle? We buy the tickets, books, and merchandise. In our world, the Spectacle has truly taken the mockingjay (fittingly something that repeats what it is told, like the Young-Girl) and commodified it. In fact, a quick internet search 16 turns up scores of mockingjay tattoos on people’s bodies, just like in the Capitol. I cannot say with certainty about all of these, but I doubt these are permanently inked onto people with the intention of it being an emancipatory symbol and furthermore, I doubt many of these people are actively trying to defeat the capitalist system. Are The Hunger Games books and movies pure Spectacle and ironically “bread and circuses” for us? Or are they part of something greater, a piece of the zeitgeist, where humanity is finally seeing naked capitalism for what it is and desiring something better? Whatever the case may be, the Hunger Games series is an interesting dystopia that warns about the dangers of rampant consumerism. Through Tiqqun’s lens, we can see the Spectacle and its hordes of Young-Girls as they appear in the Hunger Games and in real life. As the purpose of Tiqqun’s book is to allow us and encourage us to see “the Spectacle wherever it hides itself; that is, wherever it exposes itself” and to be able to see what is not Spectacle, perhaps this will help us understand how it is resisted in literature and in the world around us (68). 17 Works Cited Capitol Couture. Lionsgate. N.D. Web. 17 Dec. 2013. The Capitol: The Official Government of Panem. Lionsgate. 2013. Web. 28 Nov. 2013. The Free Dictionary. Farlex Inc. N.D. Web. 1 Dec. 2013. The Hunger Games. Dir. Gary Ross. Lionsgate. 2012. Netflix. The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Dir. Francis Lawrence. Lionsgate. 2013. Film. The Hunger Games Wiki. Wikia.com. N.D. Web. 1 Dec. 2013. Tiqqun. Raw Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl. Trans. Unknown. Editions Mille Et Une Nuits, 2001. PDF file. Travers, Peter. “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire Movie Review.” Rolling Stone. 15 Nov. 2013. Web. 30 Nov. 2013. 18