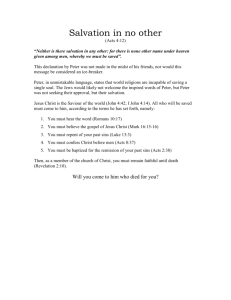

Salvation, theology and organization theory

advertisement