A preliminary distinction: Ethics of Justice and Ethics of Care

advertisement

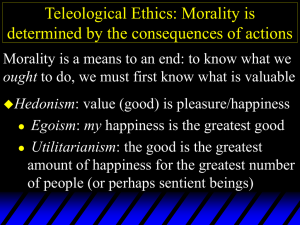

Today’s Lecture • • • • • • Grade spreadsheet Turnitin.com Study session on Monday 18th Final Exam and office hours Finishing Mill Virginia Held Grade spreadsheet • I have place an undated grade spreadsheet on the course website. Please check to ensure that the data matches what you have (this will be the last chance to do so before the exam). • If there are any discrepancies, come and see me. Turnitin.com • Remember that if your assignments are not in Turnitin.com by Friday you will receive a zero on the relevant assignment. • There is no negotiation on this one, so don’t leave this task to the last minute. • If your days of grace are giving you until Monday to hand in your paper, come and see me. Any paper handed in after Friday at 4:00 will NOT be marked by the exam. Study session on Monday 18th • There will be a study session on Monday the 18th, from 1100-1300 (or 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m.). This will be held in Talbot College room 305 (NOT 310 … they are removing asbestos from the room). You don’t have to stay for the whole period, if you come at all. Attendance is strictly voluntary. But you may be able to help each other out. • Bring ideas and talk stuff over. I won’t be able to give you any substantive answers, as that would defeat the purpose of the exam. But I can referee your discussion (i.e. if you need a referee). Final Exam and office hours • Don’t forget that the final exam is on Tuesday, the 19th, at 9:00 a.m. • The location, remember, is TC 343. • Also, I will choose the exam questions from the first fifteen questions on your original handout of possible exam questions (unfortunately we will not be getting to either Rawls or hooks - so drop questions 16 and 17). • My final office hours for this course are this week. I will be submitting your final grades on Friday the 22nd, so if you have any questions about grades (or you want to challenge grades), seek me out before the 22nd. Utilitarianism: Chapter Two • Note also that Mill does judge types or classes of action, and the feelings giving rise to them, relative to the Greatest Happiness Principle. One cannot appropriately use an appeal to utility for one’s own benefit if one’s action is clearly tied to the diminishment of the aggregate happiness of the whole ... or the relevant part of the moral community. Utility is not mere expediency (FP, p.691). Utilitarianism: Chapter Two • To the objection that we don’t have enough time to judge the merits (i.e. the consequence to the aggregate happiness of the moral community) of each action we take Mill offers two important responses (FP, p.692). • (1) The Utilitarian is reasonably supposing that given the already extensive experience of humanity, we have a rich repository of knowledge about what types of actions are conducive to happiness and what are not (FP, p.692). • (2) The Utilitarian need not commit themselves to first testing each individual action against the Greatest Happiness Principle before acting (FP, p.692). Utilitarianism: Chapter Two • This second response generates a distinction, important to subsequent discussions of Utilitarianism, between Rule and Act Utilitarians. • Act Utilitarians advocate the view that each individual action should be tested against the Greatest Happiness Principle (or some such supreme Utilitarian principle) before we can responsibly embark on that action. • Rule Utilitarians recognize the need for, what Mill calls, secondary principles which can themselves be deduced from the supreme Utilitarian principle. These ‘intermediate generalizations’ highlight what types or classes of action conform, or do not conform, to the supreme Utilitarian principle (FP, p.692). Utilitarianism: Chapter Two • Rule Utilitarianism allows for the development of rules in one context which can be used to decide the right and the wrong in relevantly similar moral contexts, thus avoiding worries about the time available to the moral agent to decide what is, or is not, the right thing to do (FP, pp.692-93). • Mill was undoubtedly a Rule Utilitarian. Utilitarianism: Chapter Three • In this chapter Mill raises a question about the sanction for the greatest happiness principle, or Utilitarian ethics more generally. • By sanction Mill means something like either the motives for obeying a given moral principle, or the source (legal, social or biological) for the perceived obligation to obey it (FP, p.693). Utilitarianism: Chapter Three • Again this is not, strictly speaking, a defense of Utilitarianism. It is rather a way of circumventing an objection which would use criteria like selfevidency, or the obviousness of moral principles, as grounds for rejecting Utilitarianism. • Or, alternatively, circumventing a rejection of Utilitarianism on the grounds that no sanction could possibly be used to inculcate it (i.e. Utilitarianism) in the general populace (FP, p.694). Utilitarianism: Chapter Three • Mill suggests that the inner experience of evidency, or the intrinsic worth of a rule, principle, or moral outlook, now enjoyed by proscriptions against theft or murder, is more often than not grounded in custom or socialization. • The evidence for such a claim partially lies in what those with differing backgrounds hold to be evident or obviously obligatory. • Also, almost any principle of action or moral principle can be inculcated with the right external sanctions and educational regimen. • For Utilitarianism to enjoy such sanctions there is merely a need for changes in education and those social institutions causally responsible for our socialization (FP, p.694). Utilitarianism: Chapter Three External and Internal sanctions • ‘External sanction’ refers to those social, legal or physical factors which generate pressure on a given moral agent to act in accordance with certain rules of conduct or behavior. • Examples of external sanctions include the fear of God’s wrath in certain religious traditions, or the fear of punishment under the law (FP, p.694). Utilitarianism: Chapter Three External and Internal sanctions • For Mill, there is no good reason to doubt that such sanctions couldn’t work in favor of the Greatest Happiness Principle (FP, p.694). • Indeed, that many understand their own happiness, or interests, to be importantly salient in the decision making processes of others when acting against or towards them speaks to the extent that social pressures may already be influencing how moral agents consider the happiness or interests of others (FP, p.694). Utilitarianism: Chapter Three - External and Internal sanctions • ‘Internal sanction’ refers to those feelings which arise in contexts where one is about to violate, or already has violated, one’s moral duty (FP, p.694). • These inner feelings can find their source in our religious traditions, from our sympathy with others, our love of another, et cetera (FP, pp.694-95). • The ultimate inner sanction, for Mill, is our conscience (FP, p.694). • Conscience is “a feeling in our own mind; a pain ... attendant on violation of duty” (FP, p.694). It is also “disinterested, and .... [connected] with the pure idea of duty” (FP, p.694). • By ‘pain’ Mill means something akin to remorse or guilt (FP, p.694). Utilitarianism: Chapter Three - External and Internal sanctions Will Mill’s emphasis on feeling as a sanction relevant to moral living undermine, rather than strengthen, an individual’s propensity to obey moral principles or laws? Mill answers this question in the negative for the following reasons. (1) Such a subjective feeling as he has highlighted (e.g. conscience) motivates even those moral agents who believe in a transcendental ground of morality (he has folks like Kant in mind here). After all, a mere belief in a transcendental ground of morality is causally ineffectual in moving someone to action, or to alternative actions than the one under consideration. What gives such a belief causal efficacy is the accompanying feeling regarding its moral worth (FP, p.695). Utilitarianism: Chapter Three External and Internal sanctions • (2) A belief in moral facts, moral truth or a transcendental ground for morality does not prevent even the best intended agent from transgressing from time to time. In fact there is no evidence that they transgress any less than those who would emphasize conscience. So even such a purportedly objective ground for ethics does not guarantee moral behavior, or make it more likely (FP, p.695). Utilitarianism: Chapter Three External and Internal sanctions • It is to be expected, suggests Mill, that (i) when the principles inculcated are too ‘foreign’ (i.e. appear too arbitrary) to the relevant individual, or (ii) when the culture advances beyond the need of them, the efficacy of inculcation will weaken, perhaps substantially, over time, or under the pressure of philosophical scrutiny (FP, p.696). Utilitarianism: Chapter Three - External and Internal sanctions • Mill believes that Utilitarianism will not fall victim to either of these factors because of, among other things, the importance of social feeling to humans living in society (FP, p.696). • By ‘social feeling’ Mill means something like the regard we give to the interests (or happiness) of others and the importance we attach to such a regard. • “The social state is at once so natural, so necessary, and so habitual to man, that, except in some unusual circumstances or by an effort of voluntary abstraction, he never conceives of himself otherwise than as a member of a body” (FP, p.696). Utilitarianism: Chapter Three External and Internal sanctions • Mill believes that such a social feeling only undergoes extension over time as long as the relevant societies progress towards greater equality and less oppression (FP, pp.696-97). • “Now, society between human beings, except in the relation of master and slave, is manifestly impossible on any other footing than that the interests of all are to be consulted. Society between equals can only exist on the understanding that the interests of all are to be regarded equally. ... [I]n every age some advance is made towards a state in which it will be impossible to live permanently on other terms with anybody” (FP, p.697). Utilitarianism: Chapter Three External and Internal sanctions • Such a happenstance, maintains Mill, will only work in favor of Utilitarianism, or any system of morality which emphasizes the importance of maximizing the aggregate good of the relevant populace (FP, p.697). Utilitarianism: Chapter Four • It is in the fourth chapter that Mill finally offers a ‘proof’ of Utilitarianism or, more particularly, the Greatest Happiness Principle (FP, p.698). • A question to keep in mind is the one he raises in the second paragraph: “What ought to be required of this doctrine - what conditions is it requisite that the doctrine should fulfill - to make good its claim to be believed?” (FP, p.698). • This is a question applicable to any theory of morality. Utilitarianism: Chapter Four • Do note something of importance in the opening paragraph of this chapter. • I have mentioned that Mill is an Epistemological Foundationalist. • Note also that he is a Naturalized Epistemologist. This means, in part, that he denies that our “first premises of knowledge” (FP, p.698) are self-evident or true a priori. They are grounded in our observations, experience and reflection on experience (FP, p.698). Utilitarianism: Chapter Four - A Defense • (1) An object can be proved visible if and only if it is seen. • (2) A sound can be proved audible if and only if it is heard. • (3) In like fashion, something is proved desirable if and only if it is desired. • (4) Each person, so far as she thinks it is possible, desires her own happiness • (5) It is a general fact about the desirability of happiness that everyone desires their happiness. • (6) Given (4) and (5), it is the case that general happiness is desired by the aggregate of persons. • (7) Given (3) and (6), it is the case that general happiness is desirable. Utilitarianism: Chapter Four - A Defense • • • • (8) If something is desirable it is a good. (9) Given (7) and (8), general happiness is a good. (10) If x is a good, then it is an end of conduct. (11) If x is an end of conduct, it is one of the criteria of morality. • (12) Given (9) through (11), happiness is one of the criteria of morality (FP, pp.698-99). Utilitarianism: Chapter Four - A Defense • Is this argument convincing? • Is there a distinction between being desirable and being morally desirable? Is something morally desirable if it is desired? Does the moral desirability of something imply that it is desired? Does it instead imply that it ought to be desired, and if so, can we distinguish an object that is desired from an object that is morally desirable? (See FP, p.675 for Bailey’s discussion of this point.) • Is this a misunderstanding of Mill’s argument? Does he mean by ‘desirable’ ‘morally desirable’? • If not, what does he mean by desirable when he speaks of the desirability of happiness? (See FP pages 698-99). Utilitarianism: Chapter Four • Note Mill’s discussion of the intrinsic desirability of various objects or properties. His version of Utilitarianism does not exclude valuing other things, such as virtue, in themselves. He does contend that they will, over time, become constitutive of what we mean by happiness (FP, p.699). • What was extrinsically desirable, because it is a means to something intrinsically desirable, can become, over time, intrinsically desirable. What’s more, as something intrinsically desirable, it can become a part of our conception of happiness, and not merely a means to it (if, that is, it was originally desired as a means to happiness) (FP, p.699). Utilitarianism: Chapter Four - Another Defense • (1) It is the case that we order our objects of desire relative to whether they promote pleasure and freedom from pain, or vice versa. • (2) It is the case that we favor or prefer those objects of desire which promote pleasure and freedom from pain. • (3) It is the case that, all things being equal, we act in accordance with what we favor or prefer. • (4) Given (2) and (3), we act in accordance with what promotes pleasure and freedom from pain. • (5) Pleasure and freedom from pain is properly described as happiness. • (6) Given (4) and (5), it is the case that we act in accordance with what promotes happiness. Utilitarianism: Chapter Four - Another Defense • (7) Given (6), happiness is the ultimate end of our (i.e. human) conduct. • (8) Under the class of human conduct there is the set of actions which constitute human moral conduct. • (9) Given (7) and (8) happiness is the ultimate end of human moral conduct (FP, pp.699-700). • Mill notes that this final argument depends, when all is said and done, on questions of fact and observation (FP, pp.700-701). A preliminary distinction: Ethics of Justice and Ethics of Care • An Ethic of Justice is any normative ethical theory which understands moral problems as involving the competing interests of ‘isolated selves’ (this term will be explained later) and requiring highly abstract principles to settle moral disputes or issues (e.g. Kantianism or Utilitarianism) (see FP, pp.720, 724). • An Ethic of Care is any normative ethical theory which prioritizes moral emotions such as sympathy or care in settling moral disputes, issues or problems (many Feminist moral theories, perhaps even Confucian moral theory) (see FP, p.722, 724). Held on Feminist concerns with the discussion thus far • (1) There is a decided emphasis on a competition of interests in the moral paradigms of the received canon of moral philosophy. As we enter and exit the Enlightenment period the moral paradigms are greatly affected by market or economic models of competition. Before that, more political models of social interaction prevailed. Either way, the ‘backdrop’ for moral discourse is decidedly public rather than private (FP, pp.718-20). Held on Feminist concerns with the discussion thus far • A question to consider as we go: What would happen to our moral discourse if our moral paradigm was the family instead of the market place ... or a state of nature? (FP, p.718) Held on Feminist concerns with the discussion thus far • (2) Essentialist views of men and women in the West have portrayed men as naturally rational or analytical, while women have been portrayed as naturally emotional and intuitive. What’s more, the rational or analytical has generally been valued over the emotional or intuitive (FP, pp.717-19). • Does this sound familiar? • These essentialist views complement the view that men are best suited for the public sphere while women are best suited for the private. Given (1), this has effectively excluded a female voice from moral philosophy (up until recently) (FP, p.718-19). Held on Feminist concerns with the discussion thus far Some of Held’s points (not directly dealing with what philosophers have said about maleness and reason [Aristotle and Rousseau and good sources for these associations]) are easily made. When attempting to distinguish humanity from nonhumanity, philosophers and others will often dwell on various cultural products like language, art, or religion. These, note, are primarily manifest, or are pervasive, in the public sphere. What we share with nonhumanity is often related to the private sphere, things like reproduction, sexual behavior (including sexual orientation/preference) and the so-called family structure. Guess who has been traditionally associated with each sphere? Held on Feminist concerns with the discussion thus far • • • • Are these essentialist views still at work? What’s a chick flik? Why is a movie a chick flik? Strong men don’t ...? What’s being ‘pussy-whipped’? (Excuse the language for the sake of the argument.) What does this imply about who should lead in a relationship? • Are women still thought to be best suited to the private sphere? Who are often thought to be the natural nurturers? Held on Feminist concerns with the discussion thus far • Feminist ethicists have directed a challenge at a number of these features of the historic discussion in Western moral philosophy. They dispute the lesser value of the emotions. Emotions such as sympathy, kindness, compassion and even self-love seem to be integral to moral living (Mill and Hume seem to agree with Feminist moral philosophers on this one) (FP, p.721). Held on Feminist concerns with the discussion thus far • Challenge has been directed at the view that women are naturally suited to child rearing while men are not. Good parenting skills are not, after all, hard-wired. Nor are women more naturally loving than men...how could such a claim be defended anyway? (see FP, p.727) • This is confirmed in studies of parenting outside of humanity. • Indeed this is why are there nurseries in Zoos and primate research facilities. • Do note Held herself would be uncomfortable with this claim. Held on Feminist concerns with the discussion thus far • The liberal self, and the idea of a human essence, have also come under fire from Feminist theorists. If the self is viewed as a product of social, as well as biological factors, what does this do to the idea of selfinterest? (FP, pp.720-21) Held on Feminist concerns with the discussion thus far • There is a methodological point at the heart of Feminist criticisms of Western moral philosophy. Imagine you have to develop an analysis of a given human evaluative concept...like ‘knowledge’. It seems reasonable to believe that you must ensure that your sample pool, from which you will derive your analysis, contains representative cases of knowledge and also cases which are clearly not knowledge. Held on Feminist concerns with the discussion thus far • There is a worry that by not ensuring that you have a representative pool of cases of knowledge and non-knowledge you may mistake certain accidental features of some cases of knowledge as necessary. A biased sample (a sample pool which lacks the appropriate scope) will yield a faulty analysis of knowledge (FP, p.721). • Imagine, for example, if your sample pool only included cases of legal knowledge, or scientific knowledge. Held on Feminist concerns with the discussion thus far • It is this type of concern that fuels the call to make sure the representative sample from which we develop our moral analyses of ‘good’ or ‘right’ has the appropriate scope. That is, we must take care to include all the spheres where moral issues arise and judgments are made. • We must, then, redirect our focus to include the private sphere (FP, pp.721-22). Held: Reason and Emotion • According to Held the priority of reason in Modern moral theory has taken two forms: Kantian and Utilitarian. • They have four features in common: (i) there is a reliance on a highly abstract principle for moral decision making, (ii) moral problems are to be solved by applying that principle, or secondary principles deduced from the ultimate/supreme principle, (iii) the rules of reason are admired or prioritized, (iv) and emotions are denigrated or judged to be problematic in moral decision making (i.e. they need to be first shaped or molded) (FP, pp.722-23). Held: Reason and Emotion • Feminist moral theorists typically take a more context sensitive approach. • That is, instead of favoring the highly abstract over the concrete/particular, Feminist ethicists tend to favor the concrete/particular over the highly abstract (FP, p.723). • What’s more, when women’s experiences are included in our sample pool of good or right actions concerns for (i) the nature of the actual relationships between embodied subjects, (ii) the particularities of the problem cases and (iii) the feelings of empathy and caring that emerge in such relationships, stand out as morally salient (FP, pp.723-24). Held: Reason and Emotion • Feminist ethicists are, according to Held, reconsidering the place of emotion in morality in at least two ways: • (1) Instead of merely recommending the development of skills in suppressing or controlling emotions, Feminist ethicists are beginning to call for the cultivation of moral emotions. If good parenting is one moral paradigm we need to better accommodate in moral theory, then we need to recognize the necessity of healthy and positive emotive responses in certain moral contexts (FP, p.724). Held: Reason and Emotion • (2) Moral subjects within a Feminist moral theory are embodied, culturally situated individuals within a web of social relationships. Certain emotions (e.g. care), or affective responses (e.g. trust), are integral to understanding good (or just) relationships and to settling conflicts within or between relationships. Moral emotions, then, may be necessary for moral knowledge or understanding (FP, pp.724-25). Held: Reason and Emotion • “Caring, empathy, feeling with others, being sensitive to each other’s feelings, all may be better guides to what morality requires in actual contexts than may abstract rules of reason, or rational calculation, or at least they may be necessary components of an adequate morality” (FP, p.725). • Is she right? Held: Reason and Emotion • Held rejects the potential objection that such an approach would be too relativist on the grounds that certain emotions or feelings may “be as widely shared as rational beliefs” (FP, p.725). • Held also makes a point of stating that a Feminist analysis of a moral problem cannot omit the political framework or outlook that informs the interactions of the subjects in the relevant moral context (FP, p.725). • Such matters as the autonomy or freedom of the individuals involved, particularly when those individuals are females in patriarchal contexts, ought to inform the judgments we make on the relevant issue (FP, p.725). • How might this affect discussions of abortion? Held: Reason and Emotion • Held suggests that minimal justice requirements of liberal societies may require “relational feelings” as much as rational abstract principles (FP, pp.725-26). • Held suggests the following areas where care, or other relational feelings, may be integral to a proper moral stance: • (1) Suffering of distant others (e.g. children). • (2) Our responsibilities to future generations. • (3) Our obligations to the planet’s well-being (FP, p.725).