What is a preceptor? - Knowledge Bank

advertisement

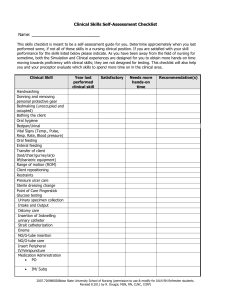

Preceptorship Denielle Beardmore, RN, Dip Project M’Ment, Ma Ed, Grad Dip Ed & T, Grad Dip Onco/Pall Care, BA Nursing, Dip App Sci (Nursing), Cert IV WAT Director Nursing Education and Practice Development Ballarat Health Services 1 Acknowledgement This project was possible due to funding made available by Health Workforce Australia. www.youtube.com/watch?v=fW8amMCVAJnoredirect=1 Come to the edge’, he said. They said, ‘We are afraid’. ‘Come to the edge’, he said. They came. He pushed them….. And they flew! Giullaume Apollinaire 4 Objectives To provide an understanding of what preceptorship is To develop an awareness of what characteristics and qualities one needs to possess in order to be a successful preceptor To develop an understanding of the theory as it relates the principle foundations of adult learning To develop knowledge in support strategies 5 Identify methods of assessing performance and providing feedback How to create a positive learning environment 6 Flying Start Series http://glm.e3learning.com.au/ Defining Preceptorship Preceptorship is not easily defined and is often interchanged in the literature with the words “mentoring”, “clinical coaching” ‘budding” or “clinical support” it is a word used to describe a means of transition. It involves a paring of one or more experienced clinician (preceptor) with a novice (preceptee). A novice could be an “undergraduate, new graduate or clinician in transition to a new facility or area of practice” (Wright, 2002) For the purpose of the Flying Start Series we consider preceptorship as: .................a period of transition for the undergraduate student or newly registered practitioner “during which time he or she will be supported by a preceptor, to develop their confidence as an autonomous professional, refine skills, values and behaviours and to continue on their journey of life-long learning” (NHS, Preceptorship Framework, 2009) Defining Preceptorship It is about..................... “an individualised period of support under the guidance of an experienced clinical practitioner which attempts to ease transition into professional practice or socialisation into a new role” (NHS, Preceptorship Framework, 2009) 9 The preceptorship relationship is usually a “short-term professional relationship with a specific end date, it is often an assigned relationship with preceptors and preceptees seldom involved in the selection with whom they will be paired………….it tends to focus primarily on the development of clinical competencies and involves some sort of judgement or evaluation of the overall clinical performance” (Yonge, Billay, Myrick, Luhanga, 2007) 10 Preceptors are responsible for evaluating the advancement of learners, ensuring they progress to develop critical thinking skills and evolve into confident and capable nurses Preceptor is the title that is used to describe an expert nursing or medical clinician who is a role model to the learner, demonstrating and personifying a competent nurse The preceptor engages in one-to-one teaching in an actual clinical setting where the information supplied is practical rather than theoretical The preceptor models the appropriate professional behaviours and ensures the development of a safe and competent learner (Baltimore, 2004) 11 Preceptorship is therefore a framework to ensure transition support processes meet best practice standards in the form of “an educational relationship which is intended to provide access to an experienced and competent role model, a means by which to build a supportive teaching and learning relationship” (Qld Health) Much of the literature on preceptorship implies that the most appropriate preceptor is one who is experienced however in many settings these choices are not available therefore the Flying Start Series considers that newly graduated practitioners can undoubtedly relate to the experiences of adapting to a new role or workplace Therefore all levels of staff should be considered as contributing to the preceptorship journey Competent Clinician Role Model Problem solver Teacher PRECEPTOR Communicator Counsellor Assessor The role of the preceptor is multifaceted 13 Small fish in a big sea 14 The aim of preceptorship is to assist the novice practitioner to adjust to their new role provide supervision to novice clinicians aide in the smooth transition of the preceptee to effectively apply and consolidate knowledge and skills delivered in educational programs act as a role model and effectively manage the identification and promotion of professional behaviours, and assist in the application of theory to practice with a particular group of patients/clients The work place as a learning environment Differs from that of the classroom, it has an added dimension………...the patient ‘Reality’ assists the novice to integrate their knowledge into practice The workplace is complex - The physical environment, staffing levels, complexity of patients, how the learners role is viewed, quality of the supervision all have an impact 16 Finding the right road 17 Issues in the work place Limited number of clinical placements or rotations Quality and quantity of the preceptors available Current and recency of practice in the speciality areas Variability in expectations from wards, students, staff and the University 18 First Impressions count The first hours a preceptee spends with you as a preceptor sets the scene for the ongoing relationship you wish to build, it is an important moment in time, appreciate the benefits that can occur with well planned time on the first day or shift. Some practical ideas for making the preceptorship relationship work might be: to identify when you can work together from a roster point of view Give the preceptee a tour of ward/dept or work area, go through the routine, and let them know how things are organised for the day Discuss dress requirements Refer them to the location and check they have access to your organisational policy and procedures Introduce the preceptee to key people in the team/area Discuss transport arrangements – can the preceptee get to the workplace for all shift times? Identify any resources the preceptee may require, ask if they have any particular support needs Ask what their concerns are if any with this placement or experience Ask them what their goals for this experience are And be sure to discuss feedback processes of how, when and what if any are the processes should they not be satisfied. So what’s in it for me? There are a number of documented benefits for implementing preceptorship some of your colleagues have said being a preceptor “challenges you” (CNS) “It can help your professional development- the students question you” (RN) “you get to share what you know” (Grad) “It eventually benefits patient care as working with a preceptee helps you to reflect on your own practice and being asked more questions helps you learn more” (CNS) “(It) improves morale” (Grade 2 RN) “it may sound a bit out there but….I do it because I can influence and shape the type of professionals that are going to work here” (CNE) “new staff see things through fresh eyes we should listen carefully to their observations” (NUM) “it helps to remind me of some of things I think are important in my profession” (Medical Registrar) Role of the Preceptor To act as a facilitator, teacher, observer, evaluator and role model Introduce the preceptee to other staff members and inter department personnel, to help integrate them into the social structure of the nursing unit Teach and supervise in connecting the theory to clinical practice 22 Assist the preceptee to coordinate patient care Share the expectations upon which evaluation will take place Communicate concerns about them to them in the first instance 23 To be or not to be a Preceptor ?????? 24 Attributes of a Preceptor Considerable literature exists listing the many attributes and characteristics of what makes a successful preceptor, hopefully you will recognise yourself in some of the following: A Preceptor is willing to support others a problem solver a critical thinker patient motivated to contribute to the learning and development of others knowledgeable in the clinical setting enthusiastic committed to quality health care outcomes a promoter of learning able to display insight and empathy to situations an exemplary role model a talent spotter a reflective practitioner able to adapt different learning styles respectful of peers non-threatening and non judgemental able to use see the funny side of things conscience of the level of influence and privilege being a preceptor has 25 Why be a preceptor? To help another person gain skills you already posses You think you have the personality and enthusiasm to give it a go To increase the number of staff able to complete specific tasks To develop your training and leadership skills 26 Dual roles With all this in mind we also need to consider that you will be juggling dual roles, although you have offered to be a preceptor and you are seen to be proficient and experienced in your clinical role you will need to consider the balance between the needs of your patients/clients/residents and the preceptee. Differences between a preceptor and preceptee may arise when expectations, roles, learning and communication styles are not made clear Expectations You are not expected to know everything but that your role is to assist the Undergraduate students, or new staff 28 Do you still want to do this????? 29 Adult Learning Principles 30 The principles of adult learning apply a practical approach, with assumptions based on a humanistic conception of self-directed and autonomous learners with teachers as facilitators of learning. The principles believe that: Adults need to know why they need to learn something before they undertake it. Preceptors’ can facilitate the reasons for knowing things by raising awareness and acting as role models. The role of the learner’s experience is important to use. As a preceptor consider the volume and quality of the learners experience and background including learning style, motivations, needs, goals and interests. Experiential techniques such as group discussion, simulation, problem solving exercises and case studies can be useful. Care should be taken to ensure that experience hasn’t closed us off to new ideas/fresh perceptions etc. Using preceptees own experience is important for their self-identify. Our experiences contribute to who we are! Adults have a self-concept of being responsible for their own decisions and lives. There is a deep need to be seen by others as being capable of self direction Preceptors need to act as facilitators, guiding development rather than considering the preceptees as empty vessel that need to be filled Adults must have a readiness to learn this means we are ready to learn things we need to know in order to function or cope with real life situations. Preceptoring in the workplace does just this, it is learning in the context of reality. Orientation to learning – Children are subject-orientated and adults are life centred, task-centred or problem-centred. We learn new knowledge, skills and attitudes best in the context of real life application. Adults respond better to internal motivators rather than external motivators however these internal motivators like job satisfaction, selfesteem, quality of life, growth and development, may become blocked by negative self concept, lack of resources and programmes that defy adult learning principles. Learning is facilitated when the preceptor has sufficient experience and expertise within an identified clinical practice area to feel confident and competent in clinical nursing skills Learners prefer and learn best from preceptors who understand and appreciate learning and continue to be learners themselves Learning is enhanced by preceptors who appropriately demonstrate empathy, non-possessive warmth, respect for the learner and consistency in their approach to the preceptor/learner relationship. 33 Each learner is unique, therefore, learning can be influenced by factors such as the individual’s emotional status, motivation and cognitive ability Adults learn best if they are acknowledged as partners in the learning experience, participating fully in the design, implementation and evaluation of the experience Learners have expectations of the experiences to be provided by the organisation by which they are employed Preceptors should ascertain what these expectations are and seek to fulfil them Learners should take primary responsibility for their skill development and take an active role in identifying areas of competency and inability 34 Learning Styles Each person differs in their preferred learning style and techniques. Learning styles generally group common ways that people learn. Everyone has a mix of learning styles. Some people may find that they have a dominant style of learning, with far less use of the other styles. Others may find that they use different styles in different circumstances. There is no right way. Nor are your styles fixed. You can develop ability in less dominant styles, as well as further develop styles that you already use well. The literature talks about many different definitions of styles in general the seven most common styles can be considered as: Verbal (linguistic) – you prefer using words, in both speech and writing Visual (spatial) – you prefer using pictures, images and spatial understanding Auditory – you prefer using sound and music Kinaesthetic (physical) – you prefer using your body, hands, and sense of touch Mathematical (Logical/theorist) – you prefer using logic, reasoning and systems Social (interpersonal/activist) – you prefer to learn in groups or with people Solitary (intrapersonal/reflector) – you prefer to work alone and use self-study Consider your own learning style, what is your preference when learning a new skill? In the first few days of working with your preceptee consider their learning style/s, by having some understanding of the different styles or preferred style Acquisition of professional skills Preceptees will be continuously gaining skills and knowledge by observing you as a role model however sometimes your facilitation of their development will need take on a more formal approach Clinical skills they will need to master will vary from simple to complex and preceptees will vary from novice with a limited range of skills to experts who have developed a wide range of skills A clinical skill should bring together both theory and practice, it is not just being able to do something, but also about Understanding the rationale or theory that underpins the intervention Strategies for teaching skills The first thing to consider is what stage of development is the preceptee at, ask questions like what course are they undertaking, what year are they in, have they been in this type of setting before, what skills and knowledge do they already possess that you can build upon? Consider what resources you have available, what is essential learning to achieve and what is desirable if it is available? You may like to identify core or essential skills pertinent to the clinical area and the preceptees stage of development If there are any assessment requirements or achievement of competencies these should be identified as a priority. Don’t forget to enlist the assistance of your colleagues to achieve these strategies. Preparation for teaching skills The first time a preceptee attempts a skills should be as controlled as possible there will obviously be a level of anxiety on their part and patients/clients should be informed Consider if the skill can be attempted away from the patient/client to reduce this stress often this is not possible as a learning opportunity has presented itself Encourage the preceptee to plan out loud, talk through the activity they are going to undertake, can they recount the steps of the process or procedure? This allows you time to anticipate any problems or gaps and potentially correct any errors Preparation time is valuable if it can be made available for both You and the preceptee. Breaking down the skill Although a skill has to be performed as a whole, there are often many components that you can break it into. Teaching the components in parts gradually integrating these into the whole allows the preceptee time to master each component Repeat practice Mastery within different settings is only acquired with repeat practice; the preceptee may have the opportunity to simulate the clinical skill in a safe environment which allows for correction of technique and feedback away from the patient or client The urge to intervene No doubt in your time as a preceptor you will feel the urge to intervene this must be resisted for reasons other than putting the patient/client or others at risk The opportunity to make mistakes is a valuable experience that can be used as a positive point of discussion Feedback on this level of performance and areas of improvement given consistently will reduce the preceptees feelings of exposure, vulnerability and anxiety A model for teaching clinical skills Peyton (1998) described a model for teaching clinical skills that can be used in simulated learning environments and the clinical setting. It is known as the “4stage approach” Stage 1 consists of a demonstration of the clinical skill at normal speed with no explanation. This allows the preceptee to see what the skill should look like in real time Stage 2 is repetition of the skill with clear explanation; the preceptee can ask questions and clarify at any point Stage 3 is where the preceptor (or another staff member) performs the skill with the preceptee providing the verbal instructions the preceptor can ask questions, clarify points, and challenge the instructions. The stage can be repeated several times in the simulated learning environment or over several days if in the clinical setting. Stage 4 allows the preceptee to perform the skill under supervision Remember to consider the risks As with any learning that occurs in a clinical setting the risks associated with the activity need to be considered, risks to patients/clients and others should be assessed when implementing any teaching of clinical skills. Patients/clients should be advised and given the opportunity to renege on being part of the learning event Peyton’s model may look time consuming and long winded however opportunity to receive feedback, reflect and practice ensures learning is grounded in best practice Professional Socialisation ‘‘Who are you?’’ said the caterpillar… ‘‘I – I hardly know, Sir, just at present’’, Alice replied rather shyly, ‘‘at least I knew who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then’’ The ‘in-betweenness’ that occurs when a undergraduate student receives a formal registration number or when a practicing professional starts in a new area can be described as a nonlinear process or journey that moves the new person through developmental and professional, intellectual and emotive, skill and rolerelationship changes, and contains within it experiences, meanings and expectations (Duchscher, 2008). Building a learning culture Health care environments that support learning are essential if preceptees are to be “effectively orientated, taught to work safely, interact in a proactive manner and contribute to ideas that benefit practice and health outcomes” (Henderson, Walker, Creedy, Boorman & Cooke, 2010) The literature confirms that health workplaces need to be accepting of different levels of staff with varying degrees of skill sets. With this acceptance comes affiliation, two prerequisites for learning. As a preceptor you can play a part in equipping staff to connect with preceptees. Connections made between the preceptee and staff in the work area can be promoted and fostered by you in your preceptor role Consider how you prepare your colleagues for the arrival of the preceptee Think of ways to ignite curiosity and interest, discover what is known about the preceptee and share it with the team In the week leading up to the arrival of the preceptee talk about what they can and can’t do and what their scope of practice will be? A learning culture .................So what is a learning culture and how do you know if you have one? These questions are often asked; the answers are complex and subject to much debate and discussion. It was Peter Senge’s 1990 book The Fifth Discipline that brought him firmly into the limelight and popularized the concept of the ‘learning organization'. Since its publication, more than a million copies have been sold and in 1997, Harvard Business Review identified it as one of the seminal management books of the past 75 years. According to Senge (1990) learning organizations are: …organizations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together. "There is nothing you can do to get another person to commit. Commitment requires freedom of choice.“ (Peter Senge 1992) The basic rationale for such organisations is that in situations of rapid change only those that are flexible, adaptive and productive will excel. For this to happen, it is argued, organisations need to ‘discover how to tap people’s commitment and capacity to learn at all levels’ To become a learning organisation is to accept a set of attitudes, values and practices that support the process of continuous learning. Providing support in the form of preceptorship could be considered one of the elements of such a process. Through learning, individuals can re-interpret their world and their relationship to it A true learning culture continuously challenges its own methods and ways of doing things 5 elements of a learning culture Senge (1990) believes that the following five elements contribute to a learning organisation: personal mastery – create an environment that encourages personal and organisational goals to be developed and realised in partnership mental models – know that a person’s 'internal' picture of their environment will shape their decisions and behaviour shared vision – build a sense of group commitment by developing shared images of the future team learning – transform conversational and collective thinking skills, so that a group’s capacity to reliably develop intelligence and ability is greater than the sum of its individual member's talents system thinking – develop the ability to see the 'big picture' within an organisation and understand how changes in one area affect the whole system. The learning workplace culture is underpinned by the values and beliefs of work and practices; it is how the culture is sustained and how individuals within the culture respond to learning events. Learning activity How does your workplace meet the 5 elements if a learning culture? Personal Mastery: How can you as a preceptor create an environment that encourages personal and organisational goals to be developed and realised in partnership with the preceptee and team? Mental Models: How can you as a preceptor discover a preceptees ‘internal’ picture of their environment and how this shapes their decisions and behaviour? Shared Vision: How can you as a preceptor build a sense of group commitment by developing shared images of the future for both the preceptee and the team? Team Learning: How does your organisation transform conversational and collective thinking skills, so that a group’s capacity to reliably develop intelligence and ability is greater than the sum of its individual member's talents? System Thinking: How can you as a preceptor assist the preceptee to develop the ability to see the 'big picture' within an organisation and understand how changes in one area affect the whole system Zero tolerance on bullying For many the transition experience is typified by fear of failure, fear of responsibility and fear of making mistakes. Clare (2002) reports that conflict and bullying of graduates in the workplace remains a national problem, with up to 25% of graduates reporting negative experiences and a lack of support from clinicians. Little wonder then that attrition of new graduates remains a significant problem in Australia. Reality shock Working in health care is more stressful, intense and technological than ever before and preceptees are expected to cope, even as some of their more senior colleagues struggle. The first three to six months is considered to be the most critical time for professional adjustment and for creating a commitment (Greenwood 2000) Kramer (1974) coined the term reality shock to describe the discovery that school-bred values conflicted with work-world values. More recently this has been cited as “transition shock” and represents the most immediate, acute and dramatic stage in the process of professional role adaptation. Reality shock The elements of transition theory amalgamate reality shock, cultural and acculturation shock, as well as theory related to professional role adaptation, growth and development, and change theory Once in the health care environment, the preceptee is immersed in a well entrenched, distinctively symbolic and hierarchical culture that exposes them to dominant normative behaviours that have been described as prescriptive, intellectually oppressive and cognitively restrictive (Kramer 1966) Many would say that in some workplaces this remains true, existing knowledge suggests that preceptees experience role performance stress, moral distress, discouragement and disillusionment during the initial months (Duchscher 2008) Transition shock Transition shock has emerged as the experience of moving from the known role of a student to the relatively less familiar role of practicing professional. Important to this experience for the preceptee is the apparent contrast between the relationships, roles, responsibilities, knowledge and performance expectations required within the more familiar academic environment to those required in the professional practice setting Appropriate preceptorship models that allow for changing roles and relationships between preceptor and preceptee, and that correlate with the evolving stages of transition are more likely to meet the dynamic needs of graduates and may enhance the job satisfaction of seasoned professionals (Rowe & Sherlock 2005, Coomber & Barriball 2006, Glasberg et al. 2007). Recognising the organisation of work Fundamental to understanding the essence of health care work is to recognise the systems used to deliver health care. What model/s do you use in your workplace? Could it be defined as primary nursing, task allocation, patient allocation, streams or a matrix model, is it easily identifiable or articulated to new staff, graduates or students. How do the patients or the rest of the interdisciplinary team know what your craft group does? Preventing drowning Much of what you will do as a preceptor during the first few weeks with the preceptee is crucial The literature has compared this transition time to “jumping into a pool at the deep end” Preceptees are nervous, have anticipated adjustment, but thrilled to finally be what they set out to be achieving What they need to prevent them from drowning is you as a preceptor to affirm them, be patience, show understanding, with a mixture of challenge and a welcoming environment that recognises them for the knowledge and skills they have acquired Assessment Blooms Taxonomy of Learning "Taxonomy” simply means “classification”, the well-known taxonomy of learning uses the behavioural paradigm to classify forms and levels of learning It identifies three “domains” of learning, each of which is organised as a series of levels or pre-requisites. It is suggested that one cannot effectively — or ought not try to — address higher levels until those below them have been covered As well as providing a basic sequential model for dealing with topics in the curriculum, it also suggests a way of categorising levels of learning, in terms of the expected ceiling for a given programme This taxonomy is useful to consider when designing assessment tools in that you need to consider what it is you are wanting to assess and at what level of the domain are you aiming Cognitive Domain This is the most-used of the domains, it refers to knowledge structures (although sheer “knowing the facts” is its bottom level). It can be viewed as a sequence of progressive contextualisation of the material Revised Cognitive Domain Revised taxonomy of the cognitive domain following Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) Note the new top category, which is about being able to create new knowledge within the domain, and the move from nouns The Affective domain Has received less attention, and is less intuitive than the Cognitive Domain. It is concerned with values, or more precisely perhaps with perception of value of issues, and ranges from mere awareness (receiving), through to being able to distinguish implicit values through analysis. Kratwohl, Bloom and Masia (1964) Psycho-Motor Domain Bloom never completed work on this domain, and there have been several attempts to complete it. One of the simplest versions has been suggested by Dave (1975): it fits with the model of developing skills put forward by Reynolds (1965), and it also draws attention to the fundamental role of imitation in skill acquisition Definitions Assessment is the judgement of performance in relation to a criteria and/or standards, it is the ongoing process of: Establishing clear, measurable expected outcomes of the learners learning Ensuring that learners have sufficient opportunities to achieve those outcomes Systematically gathering, analysing and interpreting evidence to determine how well learners learning matches our expectations/outcomes Using the resulting information to understand and improve learners learning (Oxford English Dictionary, Macmillan Dictionary) Types of assessment practices Summative assessment Summative assessment is provided at the end of the learning experience or cycle in order to gain a measure of how well the learner has performed against the standards of the intended learning outcome. Summative assessment is the grading of learning. Activities associated with summative assessment result assists you to make judgements about the learners achievement at certain relevant points in the learning process or unit of study they can be used to formally measure the level of achievement of learning outcomes and can also be used to judge programme, teaching and/or unit of study effectiveness. Formative assessment Formative assessment is predominantly used to provide formative feedback to learners on their progress. Consequently, formative assessment happens during learning and is an integral part of learning and teaching. It helps learners to identify: how they are learning if they are meeting the standards expected of them for intended learning outcomes if there are any problems or issues they are having in meeting intended learning outcomes any ‘incorrect’ learning of knowledge or skills Formative assessment usually takes place during day to day learning experiences and involves ongoing, informal observations throughout the term, course, semester or unit of study it is very applicable and helpful during early group work processes Formative assessment requires you to create a safe environment for learning in order for learners to take risks in their learning and be able to admit to, and learn from, their ‘mistakes’. Activities associated with formative assessment do not result in an evaluation. Information about what a learner knows, understands and is able to do is used by both the teacher/facilitator and the learner to determine where learners are in their learning and how to achieve learning goals. It is the practice of building a cumulative record of learner achievement Diagnostic assessment Although less common, there is another broad category of assessment known as diagnostic assessment. This type of assessment involves identifying the learner’s prior knowledge and skills about an area of learning Often the diagnostic assessment is used to determine how to develop a program that matches the learner’s needs with the intended learning outcomes. Diagnostic assessment is frequently provided at the beginning of the learning experience or cycle in order to allow you to develop a curriculum program that builds on learner’s knowledge and skills A pre-course online test or quiz that learners complete prior to beginning their course may be an example of a diagnostic assessment tool. You would use this learner data to modify or update the curriculum program to accommodate their learning gaps and/or strengths, or to help learners monitor their own learning progress during the semester Adapted from Sydney University 2012 Methods of assessment Assessment methods may also be known as assessment approaches, assessment activities or assessment strategies. Formative assessment has been recognised in most university based curriculums; thus to establish good assessment practices you should incorporate both formative and summative assessment types as part of the assessment strategy. Exams and assignments are used widely within the undergraduate and post graduate health disciplines. Negotiated and simulated learning events (SLE) are emerging approaches that are gaining interest Methods/Types of assessment Once you have determined whether you require diagnostic/ formative/ summative assessment type, you should identify appropriate assessment strategies and activities that will support the learner to meet the intended learning outcomes for program/course There are several assessment approaches that are used some of which you will be familiar with others less so. You will also find that you may tend to use one type more readily than other. This may be due to your exposure to the different types of assessment or your confidence with developing tools using this method Different methods of assessment provide the means of ensuring that learners are able to demonstrate the range of their abilities in different contexts. Selected response assessment Examinations It is a common misconception that examinations are a type of assessment rather than an approach. An examination defines the conditions under which student's abilities will be tested. They usually restrict the time and place where the assessment task will be performed. Selected response assessment – Assignments Assignments are unsupervised pieces of work that often combine formative and summative assessment tasks. They form a major component of continuous assessment in which more than one assessment item is completed within the semester. Restrictions in format, such as word limits and due dates, are often put on the assessment task to increase their practicality Negotiated Negotiated assessment involves agreements between staff and learners on issues associated with learning and assessment The most common negotiation method is to develop a written learning contract that outlines the conditions of assessment Selected response assessment – short answer Slightly less structured than multiple-choice questions, short answer questions are often used in examinations to award a few marks as a "starter", followed by a question which requires more writing. They are most effective when there can be no disagreement about acceptable answers. As with multiple choice questions, they are convenient for use when a number of assessors will mark the papers, and all alternatives can be considered. For formative assessment, such questions are often used in class questioning, or in simple informal tests to check recall. Selected response assessment – Multiple choice questions Multiple-choice questions (MCQs) are sometimes referred to as “objective” tests, although the only thing which is more objective about them than other forms of assessment is the standardisation of the marking scheme. They consist of a "stem", which usually takes the form of a question. The learner then has to choose from a number of "items", which are alternative answers. In most forms, one of these is the correct answer (although there are variants which allow for a number of correct answers), and the others are "distractors". MCQ are useful for easy administration to large numbers of learners, especially where marking is to be done by assistants rather than the test-setter. They are effective for testing sheer knowledge and memory, and for problemsolving in convergent subject areas, good MCQs are much harder to design than you think Essay response assessment An essay is a traditional form of assessment in relatively academic and some professional areas. It takes the form of a piece of writing specially composed by the learner to address a question or topic set by the teacher, usually within a set word-limit. It is extremely flexible and easy to set: Things to consider when using this method of assessment Essays require a wide range of skills, some of which may not be relevant to what you need to assess Essays written outside of a class are particularly open to plagiarism Setting an essay at the beginning of a module of learning to be completed by the end may mean that the learner focus solely on the efforts to meet the topic rather than the content Learners usually put a lot of effort into their essays: they are entitled to a reciprocal effort in feedback, unfortunately essays are easy to set but very time-consuming to mark Essay response assessment – Problem sheets Problem/ work or example-sheets are traditional formative assessment devices in maths and science disciplines, but are also found in professional disciplines such as law, accountancy and health. Learners are issued with a list of examples to be worked through in time for the next session. They may well be self- or peerassessed, and the teacher may or may not see them. Problem worksheets can be used with most programs or courses in which there is a substantial element of intellectual skill involved, where this can be exercised without recourse to complex equipment which learners may not be able to access. The preparation of problem sheets is very time-consuming. They have to be devised so as to focus only on the material covered to date, and yet to make use of that material comprehensively. Take careful note of feedback about how long such problems take the average learner: it is easy for the confident teacher to under-estimate how long they will take the struggling learner. It is fairly common practice to make the examples more difficult as the learner works through the paper. This ensures that there is something for everyone, you can also gauge where the group is at. You could develop the sheet as a teaching device, by building later examples on earlier ones. Performance Assessment – Practicum This is the most obvious form of assessment: observe someone doing something to see if they can do it properly. It is the recommended default form for competency-based programmes such as NVQs (National Vocational Qualifications, in Australia). For any area in which performance itself is not enough, direct observation needs to be supplemented by other methods. NVQs recommend oral questioning, to get at the rationale of performance. You will also need to consider how many observations will be needed..........one is not enough; observation is an extremely expensive way of assessing. Prior to observing clear assessment criteria will need to be developed: reliability is only assured when everyone engaged in the assessment process is perfectly clear about what is being looked for, and what evidence is required to determine competence. Developing observation protocols is not a trivial activity. One of the difficulties with assessing by direct observation is that some topics are far more complex than others and have multiple levels of skills required to be demonstrated in context. Collection and retainment of evidence also needs to be considered to remove the possible problems or “he says she says” When evidence consists of check-lists, ensure that the learner has a copy as soon as possible, and that there is an opportunity for dissenting views of a particular occasion of observation to be recorded. Performance Assessment – Reflective Journals/Self assessment This type of assessment it is about getting learners to develop the skills and judgement to assess themselves. Clearly it applies mainly to formative assessment, but it is none the less important for that Learners who are capable of assessing themselves are already half-way to being reflective practitioners. It is part of their development that they should no longer be entirely reliant on their teachers to assess them. It is often thought that given the chance of self-assessment, learners will always mark themselves more highly than their teachers would. If the self-assessment is a short-cut to passing a module or not, this might be the case, but their judgements—even in the case of “immature” adolescents— often prove to be remarkably accurate or even conservative. Performance Assessment – Simulation Simulations vary from the realistic emergency event simulator, through the pared-down role-play, to the stylised reconstruction of a clinical scenario on a power point. It is not so much the external circumstances which are simulated, as the decision-making, skill and practice of the practitioner working with them. Simulations are special cases of games. Simulation is good to use wherever there is a need to move closer to the reality of practice: where the text-based casestudy does not convey the urgency of decision-making, where there is a need to move away from the reality of practice because of risk or where there may be little opportunity (one hopes) for direct real-life observation of dealing with an aggressive client or patient, health or safety emergency, or particular kind of equipment fault. Given that what you may want to simulate may be something which is dangerous in real life, it should go without saying that it will require special attention to health and safety precautions The actual assessment, as ever, needs to be based on clear principles, with established criteria. Is it enough, for example, for the learner to produce the desired result, or are there process issues to be observed as well? Should the event be recorded on video, so as to have a record that can be discussed later and feedback given? Performance Assessment – Simulation There is more scope for the use of simulation than you might think. Have you thought of: "In-tray" exercises, in which the practitioner is faced with a pile of situations, events, situations of an everyday shift, and a set period within which to prioritise them and respond appropriately? You could think about a handover or prioritising care for a number of patients with competing demands "Alternative history" exercises: the participant is presented with a (fabricated) article or report which presents research findings which are at variance with the conventional best practice on a subject: he then has to prepare a response outlining how such evidence—if true—would impact on what we already think we know about the subject? Decision Mazes in which everyone starts with a case-study, and several alternative courses of action: each choice leads to a different outcome, which is described together with further alternatives, and so on? This idea could be used to build an algorithm for the actions and inventions required in a basic or advanced lie support scenario. Performance Assessment – Case Studies Ranging from simple vignettes illustrating issues in the practice of a discipline, through to complex sets of documentation which may require analysis and research. Questions may be short answer: "Was Anne within her rights to insist on an appointment? What legislation governs this situation?" to complex plans for changing practice, or proposals for the redesign of a service. Case studies are excellent for assessment of application of principles to real-world situations. They have the potential to reach all the way up Bloom's original taxonomy to "synthesis" and "evaluation". Case studies also provide useful information for formative purposes, including diagnosis of problems, because answering the questions or meeting the requirements is often a multi-stage process. Performance Assessment – Portfolios A Portfolio" covers a multitude of variations: from the portfolio of pictures, to the assembled notes and reports of a manager. What they have in common is being a collection, usually of items which were prepared for a purpose other than that of assessment. A portfolio is useful, if not essential, for the Recognition of Prior Competency (RCC). The portfolio consists of evidence assembled to show how the learner can meet specified learning outcomes or assessment criteria. The portfolio is most valuable for the assessment of vocational or professional practice—including work experience. Portfolios rapidly become enormous, and finding one's way around them can be very difficult and time-consuming What is competency? The Australian Health Practitioner Registration Authority (AHPRA) defines competency as “The combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values necessary for the health practitioner to practise at a standard acceptable to clients and others in the profession with similar background and experience. Competent means ‘having the requisite abilities or qualities’. Competency is a broader concept than the ability to perform individual workplace tasks and comprises the application of all the specified technical and generic knowledge and skills relevant for an occupation. Particularly at higher qualification levels, competency may require a combination of higher order knowledge and skills and involve complex cognitive and meta-cognitive processes such as reflection, analysis, synthesis, generation of ideas, problem solving, decision making, conflict resolution, innovation, design, negotiation, strategic planning and selfregulated learning) Australian Govt Website (DEEWT) How do we know someone is competent? After completing a competency based assessment. Just as a learner-driver must demonstrate they can drive a car by actually taking the examiner for a drive, so too must other learners demonstrate that they are competent by undergoing an assessment process Assessment may involve a practical demonstration of skills, some form of written assessment, such as a test or preparation of a report, or a presentation or interview An individual can be assessed during their training, at the end of their training, or without even undertaking any training (for example if they believe they are already competent) The method and timing of assessment will vary depending upon the assessor, the learner and the competency being assessed. What standards are candidates assessed against? In order to assess whether a learner is competent, they are judged against established standards (also known as benchmarks) These standards have been developed by industry and are called competency standards. Competency standards may also be referred to as units of competency Competency standards are documents that define the competencies required for effective performance in the workplace in specific industries Competency standards include the essential information needed to assess a learner Competency and time Competency is the consistent application of knowledge and skill to the standard of performance required in the workplace. It embodies the ability to transfer and apply skills and knowledge to new situations and environments Competency is demonstrated to the standard required in the workplace and covers all aspects of workplace performance including: performing individual tasks; managing a range of different tasks; responding to contingencies or breakdowns; and dealing with responsibilities of the workplace, including working with others. Competency requires not just the possession of workplace related knowledge and skills but the demonstrated ability to apply specified knowledge and skills consistently over time in a sufficient range of work contexts What is Competency Based Assessment (CBA) Competency-based assessment is commonly linked to competency-based training and forms the basis of the Vocational Education and Training (VET) system in Australia The catalyst for the shift to competency-based assessment was the need for a system which focused on industry determined benchmarks (competency standards) and promoted national consistency across the training sector in Australia (Bridge 1997) In 1995, national arrangements for assessment for the purposes of issuing qualifications under the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) were agreed to These arrangements assist organisations to determine whether or not a person has achieved a level of competency required by industry Education Network Australia Assessment under a competency based approach, is the process of collecting evidence and making judgments on the nature and extent of progress towards the performance requirements set out in a standard (VEETAC cited in ACTRAC 1994, p.1) Assessment is based on the actual skills and knowledge a person can demonstrate in the workplace Where competency standards for an industry/occupation do not exist, performance can be assessed against a set of criteria such as award classifications, standard operating procedures and performance agreements Features of competency-based assessment The notable features in competency-based assessment are: competency-based assessment is criterion based - a person is assessed not in competition with others but against standard criteria or benchmarks; competency-based assessment is evidence based - decisions about whether a person is competent are based on the evidence they provide to the assessor; and Competency-based assessment is participatory - the person being assessed is involved in the process of assessment and has the scope to negotiate with the assessor the form that assessment activities take. In addition, competency-based assessment does not have to be limited to a narrow set of methods. A range of assessment tools or instruments can be used as long as the person has the opportunity to demonstrate their competence in relation to a work role/task. For example, assessment activities may involve: observation in the workplace; practical demonstration and questioning; written tests and essays; projects; and simulations and role plays (Education Network Australia, 2010) Key features of CBA Regardless of the method used there are four key features of competency-based assessment that hold paramount These are: validity, reliability, fairness and flexibility In keeping with these four features, competency-based assessment should always use an integrated approach which covers all aspects of work performance including: task skills (being able to perform individual tasks); task management skills (being able to manage a number of different tasks); contingency management skills (being able to respond to problems/irregularities that arise); and job/role environment skills (being able to work with others CBA and Validity Validity in a competency-based system refers to assessments that cover a range of skills and knowledge and integrate them with their practical application. Judgments to determine competency should be based on evidence gathered on a number of occasions and in a variety of contexts. Reliability Means that assessment practices should be regularly monitored and reviewed to ensure that there is consistency in the interpretation of evidence It should also be noted that if competency is being assessed for the purposes of issuing qualifications under the AQF, then assessors must be: competent in the national competency standards for assessment; have been deemed competent in the standards being assessed; and must have a detailed understanding of the standards and their use as benchmarks within the context and culture of the workplace/sector/industry. (Community Services Training Package 2010 CBA and Fairness Fairness relates to practices and methods that are equitable to all groups being assessed. Provisions must be made for assessee to challenge assessments if they are unsatisfied with the process or the outcomes. CBA and Flexibility Flexibility in assessment refers to processes that provide for the recognition of competencies regardless of where they have been acquired. For example, competencies can be achieved: through formal or informal training; through work experience; through general life experiences; or through any combination of the above. (Community Services Training Package 2010) KISS PRINCIPLE 99 4 Domains Professional Practice Provision & Coordination of Care Critical Thinking & Analysis Collaborative & Therapeutic Practice 10 Competency Units 1. Practices in accordance with legislation affecting nursing practice health care 2. Practises within a professional and ethical nursing framework 3 Practises within evidencebased framework 4. Participates in ongoing professional development of self and others 5. Conducts a comprehensiv e and systemic nursing assessment 6. Plans nursing care in consultation with individuals/gr oups, significant others and the interdisciplina ry health care team 7. Provides comprehensiv e, safe and effective evidencebased nursing care to achieve individual/ group health outcomes 8. Evaluates progress towards expected individual/ group health outcomes in consultation with individuals/ groups significant others and interdisciplina ry health care team 9. Establishes, maintains and appropriately concludes therapeutic relationships 10. Collaborates with the interdisciplina ry health care team to provide comprehensiv e nursing care Competency Elements 3 7 5 4 3 4 8 2 5 4 Guiding Cues 100 Professional Practice 1. Practices in accordance with legislation affecting nursing practice health care 1.1 Complies with relevant legislation affecting nursing practice and health care 1.2 Fulfils the duty of care 2. Practises within a professional and ethical nursing framework 1.3 Recognises and responds appropriately to unsafe or unprofessional practice 2.1 Practices within a professional and ethical nursing framework Cues 101 Critical Thinking & Analysis 4. Participates in ongoing professional development of self and others 3. Practises within evidence-based framework 3.1 Identifies the relevance of research to improving individual/ group health outcomes 3.2. Uses best available evidence, nursing expertise and respect for the values and beliefs of individuals/ groups in the provision of nursing care 3.3 Demonstrates analytical skills in accessing and evaluating health information and research evidence 3.4 Supports and contributes to nursing and health care research 3.5 Participates in quality improvement activities Cues 4.1 Uses best available evidence , standards and guidelines to evaluate nursing performance 4.2 Participates in professional development to enhance nursing practice 4.3 Contributes to the professional development of others 4.4 Uses appropriate strategies to manage own responses to the professional work environment 102 Provision & Co ordination of care 6. Plans nursing care in consultation with individuals/ groups and the interdisciplinary health care team 5. Conducts a comprehensive & systematic nursing assessment 5.1 Uses a relevant evidence-based assessment framework to collect data about the physical sociocultural and mental health of the individual/ group 5.2 Uses a range of assessment techniques to collect relevant & accurate data 5.3 Analyses & interprets assessment data accurately 6.1 Determines agreed priorities for resolving health needs of individuals/ groups Cues 6.2 Identifies expected & agreed individual/ group health outcomes including a time frame for achievement 6.3 Documents a plan of care to achieve expected outcomes 6.4 Plans for continuity of care to achieve expected outcomes 103 Provision & Co ordination of care 7. Provides comprehensive, safe & effective evidence-based nursing care to achieve identified individual/group health outcomes 7.1 Effectively manages the nursing care of individuals/ groups 7.2 Provides nursing care according to the documented care or treatment plan 7.3 Prioritises workload based on the individuals'/ group’s needs acuity and optimal time for intervention 7.4 Responds effectively to unexpected or rapidly changing situations 7.5 Delegates aspects of care to others according to their scope of practice Cues 7.6 Provides effective and timely direction and supervision to sure that delegated care is provided safely and accurately 7.7 Educates individuals/ groups to promote independence and control over their health 7.8 Uses health care resources effectively and efficiently to promote optimal nursing and health care 104 Provision & Co ordination of care 8. Evaluates progress towards expected individual/group health outcomes in consultation with individuals/groups significant others and interdisciplinary health care team 8.1 Determines progress of individuals/ groups toward planned outcomes 8.2 Revises the plan of care and determines further outcomes in accordance with evaluation data Cues 105 Collaborative & Therapeutic Practice 10. Collaborates with the interdisciplinary health care team to provide comprehensive nursing care 9. Establishes, maintains & appropriately concludes therapeutic relationships 9.1 Establishes therapeutic relationships that are goal directed and recognises professional boundaries 9.2 Communicates effectively with individuals/ groups to facilitate provision of care 9.3 Uses appropriate strategies to promote an individual’s/ group’s selfesteem, dignity, integrity and comfort 9.4 Assists and supports individuals/ groups to make informed health care decisions 9.5 Facilitates a physical, psychosocial, cultural & spiritual environment that promotes individual/ group safety & security Cues 10.1 Recognises that the membership & roles of health care teams & service providers will vary depending on the individual’s/ group’s needs & health care setting 10.2 Communicates nursing assessments & decisions to the interdisciplinary health care team & other relevant service providers 10.3 Facilitates coordination of care to achieve agreed health care outcomes 10.4 Collaborates with the health care team to inform policy & guideline development 106 Assessing: Use your head not your heart 107 Is making a bed a competency or a skill? 108 Competency vs. Skill • Competency is broad • Encompasses skills & knowledge • May require more than one skill to achieve a competency 109 ANMC Competency Based Evaluation Legend Criteria Competency Rating Independent Proficient Advanced Beginner Novice Practices in a safe, accurate, coordinated and effective manner. Practices in a safe, accurate, coordinated and effective manner little need for guiding cues. Practices in a safe, accurate and coordinated manner most of the time, with some guiding cues required. Practices in a safe manner when frequent guiding cues are given. Unsatisfactory Unable to demonstrate safe practice, adequate knowledge base and/or appropriate professional behaviour. Not Applicable Not observed, not applicable or unable to assess. (Adapted from Benner & Bondy) 110 MINIMUM COMPETENCY RATING YEAR 1 YEAR 2 YEAR 3 YEAR 3 Preceptorship Advanced Beginner Proficient Proficient Independent CRITICAL THINKING AND ANALYSIS Novice Advanced Beginner Proficient Proficient PROVISION AND COORDINATION OF CARE Novice Advanced Beginner Proficient Proficient COLLABORATION AND THERAPEUTIC PRACTICE Novice Advanced Beginner Proficient Proficient DOMAINS/ COMPETENCY UNIT PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE This tool is to be used in conjunction with: ANMC: National Competency Standards for the Registered Nurse 2006 and Principles for 111 the assessment of National Competency Standards. “We must become the change we want to see in the world.” Mahatma Gandhi (1869 – 1948) 112