M_Godley_et_al_-_AHSR_2007_Poster

advertisement

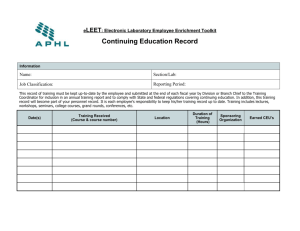

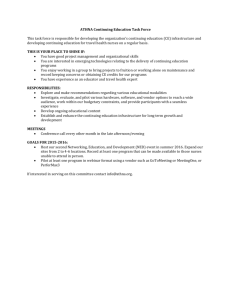

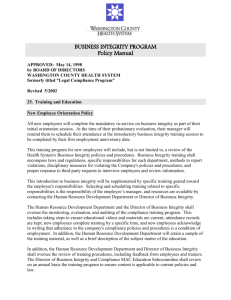

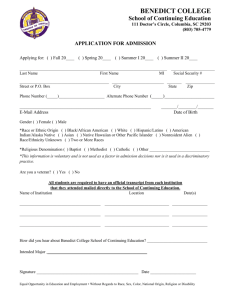

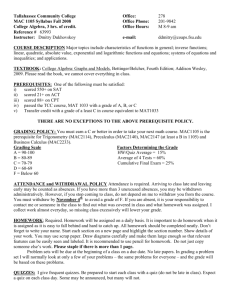

A low-cost intervention for improving continuing care initiation, engagement, and clinical outcomes: Findings from a randomized pilot study of telephone continuing care Mark D. Godley, Ph.D.1, Janet C.Titus, Ph.D. 1, Rod R. Funk, B.S.1, Matthew G. Orndorff, M.A.1, & John F. Kelly, Ph.D.2 1Chestnut Introduction Ever since the McLellan et al. (2000) publication on treating addiction as a chronic illness, there has been increasing calls to move from single specialty treatment episodes of care to ongoing continuing care strategies to manage substance use disorders. Unfortunately, most health services studies of continuing care demonstrate poor initiation rates (Donovan, 1998; Godley & Godley, in press). More recently, researchers are investigating continuing care strategies that are more “assertive,” focused on decreasing the participation burden to patients after they leave primary treatment (Dennis, Scott, & Funk, 2003; Godley et al., 2007; McKay et al., 2007). McKay (2006; 2007) reviewed the published continuing care research and found support for adaptive strategies that featured clinician-initiated contact, monitoring patient functioning, and providing assistance commensurate with need over an extended period of time, which is consistent with the chronic relapsing nature of substance use disorders. Telephone continuing care is an example of such an approach. Previous telephone continuing care research has shown mixed results, but may be more useful for lower severity patients (McKay et al., 2004). The purpose of the present intent-totreat randomized trial of telephone continuing care was to examine the feasibility of provider-initiated calls to patients and initial clinical effectiveness with a full and lowerseverity sample of adults after residential treatment. Health Systems, Bloomington, IL; 2Massachusetts General Hospital & Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA Method Results Participants Protocol Adherence • Participants were recruited from sequential admissions • All TCC calls were audio-recorded and one was randomly selected each week and reviewed by the PI prior to an individual supervision meeting with each volunteer. • 104 adults admitted to residential treatment for substance use disorders • 60% were male; 76% Caucasian; 70% age 21-40; 85% single; 65% with current criminal justice involvement; 64% with 1+ prior treatment episodes • 97% met DSM IV criteria for 1+ substance use disorders in their GAIN intake interview 100% 90% 70% • Completed an average of four calls per recipient. 60% • Consenting patients were randomly assigned to participate in a control group (Usual Continuing Care-UCC) or an experimental group (Telephone Continuing Care-TCC). Figure 1: Adherence Items for Telephone Condition • The GAIN was used to assess patients at intake to residential, three, and six months following residential discharge. • This low intensity intervention has smaller treatment effect with full sample, thus future studies need larger samples to decrease probability of Type II error. 50% 40% 30% Intake 3 TCC Did your telephone support counselor ask whether you had used alcohol or drugs since leaving treatment or since your last call? UCC 6 TCC-LS UCC-LS NS for total sample. ANCOVA condition main effect at 3 months, F(1,67)=4.25, p<.05, d=.37 for TCC-LS. 78% Did your telephone support counselor offer suggestions helpful to your recovery? H2: Will experience greater abstinence and fewer A0D related problems. Study Procedures • There was mixed support for clinical effectiveness of TCC, however, analysis of TCC-LS demonstrated stronger clinical outcomes and most patients liked TCC. 80% Design H1: Will be more likely to participate in and receive more continuing care. • Counselor-initiated TCC reduces the response and cost burden to patients and results in higher initiation and engagement but takes significant effort to complete calls. Figure 3: Percent of Days Abstinent • Number of attempts to complete a call was 6.9 per TCC participant • It was hypothesized that relative to participants in UCC, the TCC participants: Discussion 81% Was your telephone support counselor kind and encouraging? Figure 4: Past Month Substance Problems (includes 11 DSM IV abuse/dependence symptoms) 92% Did your telephone support counselor ask you to follow through on things like making aftercare appointments or trying a new social or recreational activity? 81% 10 • Biological drug tests for cocaine and cannabis at three-month follow-up compared with GAIN self-report: Kappa =.69; False negative rate 6.8%-no between group difference. 89% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 8 100% • Using volunteers to conduct TCC appears to be feasible; regular review of audio recordings and feedback is recommended. • The cost of supervising TCC is less than most EBPs because the protocol is simple and recorded session time is 20 minutes or less. • Conducting TCC longer than three months may be warranted since days abstinent finding decreased after TCC phase ended and most participants felt TCC should be available longer than 3 months after residential discharge. 9 Did your telephone support counselor ask if you were attending support group meetings, counseling, or other kinds or formal support? • The method of selecting low severity patients in this pilot study may have increased Type I error possibility 7 % responding almost always or always 6 5 • 76% of eligibles enrolled and follow-up rates were 90% at three months (end of active TCC phase) and 85% at six months. • Outcome data was re-analyzed after excluding most severe quartile on pre-treatment days of AOD use, creating low severity subgroups: TCC-LS and UCC-LS. Figure 2: Continuing Care Initiation and Sessions Attended 3 100% 10 2 90% 9 1 79% Interventions 80% Usual Continuing Care (UCC): Upon discharge from residential UCC group received a continuing care plan, referral to outpatient clinic, and advice to continue 12-step meetings. 70% 7 60% 6 50% 5 Telephone Continuing Care (TCC): A positive, nonconfrontational intervention designed to provide social support for recoveryoriented behaviors and to provide referral advice for relapse and other problems. Para-professional volunteers were recruited and trained to serve as telephone support counselors. In addition to receiving UCC, specific elements of TCC included: • One call/week for the first month; one every other week for next two months. • Call duration: ≤20 minutes. • Establish rapport; inquire about urges to use since last call. • Further research is needed to replicate TCC and validate a selection method for lower severity patients discharged from residential care. 4 40% 8 37% 4.0 4 30% 3 20% 2 10% 0% 0 References Intake 3 TCC UCC 6 TCC-LS UCC-LS Significant main effect for TCC at 3 months—ANCOVA F(1,91)=6.30, p<.05., d=.-.39. Significant main effect for TCC-LS at 3 months-- ANCOVA, F(1,67)=9.86, p<.01., d=.-.51. Figure 5: Participant Satisfaction with Telephone Continuing Care 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 0 Percent Initiated CC TCC Median Number of Sessions UCC Both the Initiation and Sessions variables are significant (p<.05). 0 Did you like receiving calls from your telephone support counselor? 89% Donovan, D.M. (1998). Continuing care: Promoting the maintenance of change. In W.R. Miller & N. Health (eds.), Treating Addictive Behaviors (2nd ed.). New York: Plenum Press. Godley, M.D., Godley, S.H., Dennis, M.L., Funk, R.R., & Passetti, L.L. (2006). The effect of assertive continuing care on continuing care linkage, adherence, and abstinence following residential treatment for adolescents with substance use disorders. Addiction, 102, 81-93. Godley, M.D., & Godley, S.H. (in press). Continuing care following residential treatment: History, current practice, critical issues, and emerging approaches. In N. Jainchill (ed.), Understanding and treating adolescent substance use disorders. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute. McLellan, A.T., Lewis, D.C., O’Brien, C.P., & Kleber, H.D. (2000). Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness`s: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284, 1689-1695. McKay, J.R. (2006). Continuing care in the treatment of addictive disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 8, 355-362. (Percent answ ering: sometimes-alw ays McKay, J.R. (2007). Extending the benefits of addiction treatment: Practical strategies for continuing care and recovery. Second Betty Ford Institute Conference, Rancho Mirage, CA. • Inquire about follow through with continuing care goals. • Provide praise for overcoming urges to use and progress toward goals. Dennis, M.L., Scott, C.K., & Funk, R.R. (2003). An experimental evaluation of recovery management checkups (RMC) for people with chronic substance use disorders. Evaluation and Program Planning, 26, 339-352. Would you recommend that telephone support calls continue for longer than the first 3 months after residential treatment? 72% McKay, J.R., Lynch, K.G., Shepard, D.S., Ratichek, S., Morrison, R., Koppenhaver, J., & Pettinati, H. (2004). The effectiveness of telephone-based continuing care in the clinical management of alcohol and cocaine use disorders: 12 month outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 967-979. (Percent answ ering Yes) • Help problem-solve ideas for goal achievement; if relapse occurred collect information/make referral to clinician. • Thank participant for attending the call, agree on date/time for next call. Most TCC participants like the phone calls and thought they should continue beyond 3 months. Contact Information: Mark D. Godley, Ph.D., Chestnut Health Systems, 720 W. Chestnut St., Bloomington, IL 61701; Email: mgodley@chestnut.org