Climate Justice Dialogue 1 John O'Neill

advertisement

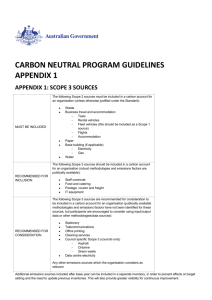

Dimensions of climate justice John O’Neill, University of Manchester Monday, 19 May 2014 Dimensions of climate Justice A number of distinct dimensions of justice have been raised by climate change and policy responses to it 1. Unequal responsibilities: who bears greater responsibility for the emissions of greenhouse gases? 2. Unequal impacts of climate change: who is more adversely affected by the extreme weather events that will increase in frequency and intensity? 3. Unequal impacts of policy responses: who benefits and who bears the costs and burdens of mitigation and adaptation policy? 4. Procedural justice: who has the power to make and affect policy responses to climate change? Scope of Climate Justice • • • • International National Intra-generational Intergenerational What does the evidence tell us about climate injustice in the UK? Low income households and other disadvantaged groups in the UK face multiple injustices as they: •contribute the least to causing climate change through their emissions •are likely to be most negatively affected by climate impacts •pay, as a proportion of income, the most towards implementation of certain policy responses •often benefit least from those same policies •are less able to participate in decision-making around policy responses and in determining practice Preston et al (2014) Climate Change and Social Justice: A Evidence Review 1. Responsibilities for emissions Emissions of the richest 10% of the population are over 3 times higher than those of the lowest 10%. The differences in emissions are particularly wide in relation to private transport, in particular air travel. Preston, I., et al 2013 Distribution of Carbon Emissions in the UK: Implications for Domestic Energy Policy JRF York Responsibilities for emissions From Gough et al. 2011 The distribution of total greenhouse gas emissions by households in the UK, CASE LSE GHG per £ From S. Abdallah et al. 2011 The distribution of total greenhouse gas emissions by households in the UK, and some implications for social policy CASE LSE More Unequal Countries Emit More C02 From: Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. The impact of income inequalities on sustainable development in London. A report written on behalf of The Equality Trust, commissioned by the London Sustainable Development Commission, 2010, http://www.londonsdc.org/lsdc/research.aspx. 2. Adverse impacts of climate change How disadvantaged different individuals or groups are to extreme weather events will depend on two factors: • Exposure: The likelihood and degree to which they are to be exposed to the outcomes of an extreme weather event such as drought, flood or heatwave. • Vulnerability: the likelihood and degree to which the event will result in a loss of wellbeing. What makes people and neighbourhoods socially vulnerable to extreme weather events? • An individual or group is more vulnerable if they are less able to respond to stresses placed on well-being. • To understand the distribution of vulnerability we need to know what factors are relevant to understanding how external stresses convert into changes in well-being. Personal factors: Biophysical characteristics of people such as age or health Environmental factors: Physical attributes of neighbourhoods, such as green space and drainage, the quality and elevation of housing Social factors: Social characteristics of people and neighbourhoods such as •levels of income and inequality •social networks and individuals’ degree of social isolation •fear of crime 3. Impact of policy responses Despite having lower emissions, lower income households bear a greater burden of the costs of policies for example on mitigation and receive fewer of the benefits • Mitigation policy to lower emissions funded through levies and charges on gas and electricity bills form a higher proportion of the expenditure of lower income households • Schemes, such as the feed in tariff for home-based renewables, are only available to higher income households with funds or the means to borrow Preston, I. et al 2013 Distribution of Carbon Emissions in the UK: Implications for Domestic Energy Policy JRF York 4. Procedural justice Procedural justice concerns the justice in the procedures through which decisions are made: •Who has the power and voice to frame and influence decisions? •Do different decision making procedures systematically favour some groups over others? All 0 % 15 1-4 % 52 4+ % 33 Class Professional and managerial Intermediate Manual 8 14 18 45 51 58 47 36 24 Income Under £10,000 £10,000 up to £19,999 £20,000 up to £29,999 £30,000 up to £39,999 £40,000 up to £49,999 £50,000 and above 19 15 10 10 9 3 56 54 51 47 41 43 25 31 39 44 50 54 Education 15 years and under 16-18 19 years and over 19 15 7 Number of political actions 57 42 43 © Environment Agency 24 33 50 Levels of participation are correlated with income and occupation Pattie, C., Seyd, P. and Whiteley P. (2004) Citizenship in Britain Cambridge: Cambridge University Press p.86 The distribution of voice and influence • Levels of participation in political action and civil society associations are closely correlated with income and occupation • Engaging vulnerable communities in decisions that affect them can help address both procedural justice and foster the development of more resilient communities Pattie, C., Seyd, P. and Whiteley P. (2004) Citizenship in Britain Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Decision making procedures • Decision making methods are not just technical tools. Their use can have implications for the distribution of benefits and burdens of policy. • Cost benefit analysis (CBA) is widely used as a way of assessing different policies. In the context of climate change and justice it is deeply controversial. • Standard CBA places lower monetary values on adverse impacts on lower income groups and future generations. Those worst affected by climate change and least responsible count least. Why is cost-benefit analysis controversial? • Since a £ is worth more for a person on lower income, in a standard CBA the values placed on costs of burdens on the poor are lower than those on the wealthy, while the values placed on the benefits of distributing goods to the wealthy are higher. • The value of a statistical life in standard CBA for a poor person is lower than that for a rich person. • ‘Discounting’ in CBA involves putting a lower value on future costs and benefits: the further in the future the lower the value will be; the higher the discount rate, the lower will future values be. © Environment Agency Conclusion • Lower income and other disadvantaged groups contribute least to causing climate change but are most likely to be adversely impacted by its effects • How disadvantaged a person or group will be with respect to potential losses in well-being will be a function of two distinct factors, their likelihood and degree of exposure to extreme weather events and their vulnerability. © Environment Agency It is vital that other responses take account of the inherent inequalities in the ways people are affected by events like floods