Core Reader TABLE OF CONTENTS

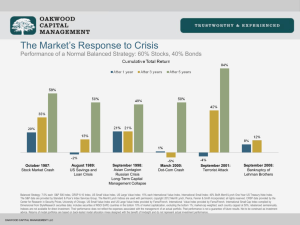

advertisement

MERRILL CORE (MERRILL 80A AND 80B) CULTURAL IDENTITIES AND GLOBAL CONSCIOUSNESS: AMERICA AND THE WORLD UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ FALL 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS I: Academic Literacies: Thinking about Reading and Writing at the University Bartholomae, David, Anthony Petrosky, and Stacey Waite. Introduction to Ways of Reading: An Anthology for Writers. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s Press, 2014. Cox, Rebecca. “Academic Literacies.” In The College Fear Factor: How Students and Professors Misunderstand One Another. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009. Swales, John. “’Create a Research Space’ (CARS) Model of Research Introductions.” Adapted from John M. Swales’s Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990. II. Merrill Core Themes Theory Merrill Core Key Terms and Phrases (working list and example) Hall, Stuart. “Ethnicity: Identity and Difference” Radical America Vol.23 no.4, 1991:9-20. Pratt, Mary Louise. “Arts of the Contact Zone.” Profession 1991:33-40. Thornton Dill, Bonnie, Amy E. McLaughlin, and Angel David Nieves. “Future Directions of Feminist Research: Intersectionality” Chapter 36 in Handbook of Feminist Research: Theory and Praxis, edited by Sharlene Nagy HesseBiber. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2007. III. The Local and the Global: “Crisis,” Immigration, and UCSC Students Redefining America McManus, Phil. “Past Policies Pushing Child Migration.” Cruz Sentinel, July 26, 2014. Santa Escobar, Veronica. “Why the Border Crisis is a Myth.” New York Times, July 25, 2014. Paarlberg, Michael. “Gangs, Guns, and Judas Priest: The Secret History of a U.S.- Inflicted Border Crisis.” The Guardian, July 23, 2014. Vargas, Jose Antonio. “My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant.” New York Times, June 22, 2011. Guttman, Nathan. “Undocumented Jews Live in Shadows of U.S. Society.” (New York) Forward, July 15, 2011. The S.I.N. Collective. Students Informing Now (S.I.N) Challenge the Racial State in California Without Shame…SIN Verguenza! Educational Foundations Winter-Spring 2007:71-90. Dominguez, Neidi, Yazmin Duarte, Pedro Joel Espinoza, Luis Martinez, Kysa Nygreen, Renato Perez, Izel Ramirez, and Mariella Saba. “Constructing a Counternarrative: Students Informing Now (S.I.N.) Reframes Immigration and Education in the United States.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 52 (5). February 2009:439-442. Merrill Core Key Terms and Phrases (last revised:8/21/2014) academia academic culture/the culture of academia academic discourse accomodation agency analysis assimilation capitalism class colonialism colonization/decolonization conscious/unconscious consciousness contact zone culture cultural diversity/cultural difference cultural identity cultural hegemony curriculum diaspora dialectic discourse diversity ethnicity Euro-centrism gender genre global /global consciousness globalization hegemony hybridity identity ideology imperialism Indigenous Interpretation Multicultural/ism Native (vs. native) other/othering pedagogy race/racialization race/class/gender/sexuality paradigm rhetoric sexuality socially constructed subject/subjectivity subjective/objective Third World (First, Second, Fourth) voice whiteness 2010 US racial and ethnic categories Third World (First, Second, and Fourth) The term ‘Third World’ was first used in 1952 during the so-called Cold War period, by the politician and economist Alfred Sauvy, to designate those countries aligned with neither the United States nor the Soviet Union. The term ‘First World was used widely at the time to designate the dominant economic powers of the West, whilst the term ‘Second World’ was employed to refer to the Soviet Union and its satellites, thus distinguishing them from the First World. The wider and economic base of the concept was established when the First World was sometimes used also to refer to economically successful ex-colonies such as Canada, Australia, and, less frequently, South Africa, all of which were linked to a First World network of global capitalism and Euro-American alliances. Very quickly, ‘Third World images’ became a journalistic cliché invoking ideas of poverty, disease and war and usually featuring pictures of emaciated African or Asian figures, emphasizing the increased racialization of the concept in its popular (Western) usage. The term was, however, also used as a general metaphor for any underdeveloped society or social condition anywhere: ‘Third World conditions,’ ‘Third World educational standards,’ etc., reinforcing the pejorative stereotyping of approximately twothirds of the member nations of the United Nations of the United Nations who were usually classified as Third World countries. As obvious economic differentials began to emerge within this group, with economic development in the various regions, notably Asia, the term ‘Fourth World’ was introduced by some economists to designate the lowest group of nations on their economic scale Recent post-colonial usage differs markedly from this classis use in economics and development studies, with the term ‘Third World’ being less and less in evidence in discourse. This has been defended by some post-colonial critics on the grounds that the term is essentially pejorative. But in the United States in particular the increasing tendency to avoid the term in post-colonial commentary, as well as the decline in the use of the terms such as anti-colonial in course descriptions and in academic texts, has sometimes been criticized as leading to a de-politicization of the decolonizing project. The term ‘Second World’ has been employed also in recent post-colonial criticism by some settler colony critics to designate settler colonies such as Australia and Canada (Lawson 1991, 1994; Slemon 1990) to emphasize their difference from colonies of occupation. The term ‘Fourth World’ is also now more commonly employed to designate those groups such as indigenous people whose economic status and oppressed condition, it is argued, place them in an even more marginalized position in the social and political hierarchy that other post-colonial peoples (Brotherston 1992). Source: Ashcroft Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin, Post-Colonial Studies: The Key Concepts. New York: Routledge, 2000: 231-232.