population growth and demographic transition

AGEC 640

Agricultural Development and Policy

Thursday, Sept. 4, 2014

• Last class

Farm and food problems: the development paradox and structural transformation

• Today

Mouths to feed, farmers to employ: population growth and demographic transition

• Next week: farm households’ response

Slide 1

Drivers of Change:

Population growth and economic transformation

• Last class:

– broad diversity of policy problems and policy actions, but also

– strong regularities (“stylized facts”):

– the development paradox, from taxing to subsidizing farmers

– the structural transformation, from farm to nonfarm activity

• Today:

– a key driver (from outside, exogenous to agriculture) is demography:

– the demographic transition

– from large to small families

– high to low death rates and birth rates

– high to low fraction of people who are children

…and other corresponding changes

Slide 2

Demographic transition

A pattern of steadily increasing population growth, followed by a period of slowing population growth.

Generally indicated as an S-shaped curve for population through time.

Slide 3

Frank Notestein (b. 1945)

Three stages of population growth

1.

High growth potential

2.

Transitional growth

3.

Incipient decline we might add…

4. Sustained decline?

?

1 2 3 4

Slide 4

1. High growth potential

Pre-industrial

Birth rate high (25-40/1000)

Death rate high

Life expectancy short

Population growth low but positive

Widespread misery

Slide 5

2. Transitional growth

Early industrial

Birth rate remains high (or rises!)

Death rate low and falling

Life expectancy rises

Population growth “explosive”

Mortality declines before fertility due to better health, nutrition, and sanitation

Slide 6

3. Incipient decline

Industrial

Birth rate drops due to desires to limit family size

Death rate low and stable

Life expectancy high

Population grows until birth rate = death rate

Characterized by higher levels of wealth and reduced need for large families for labor or insurance.

Also driven by female empowerment, female education and female labor market participation.

Slide 7

A Stylized Model* of Demographic Transition

The gap between birth and death rates is the population’s “rate of natural increase”

( ≈ population growth)

* In what sense is this a model?

Slide 8

An actual demographic transition

Sweden’s population growth rate peaked at about 1.5% per year, in the late 19 th century

Slide 9

A different demographic transition

Mauritius’ peak pop. growth rate was over 3%/year, twice that of Sweden, because its death rate fell so fast…

Slide 10

A third kind of transition

Mexico’s peak population growth was even faster, because its birth rate fell slowly…

Slide 11

Message: Birth rates > death rates, country is still in stage 2 of the demographic transition

Slide 12

Birth and death rates depend in part on age structure and “population momentum”

Slide 13

A very young age structure: the population pyramid for Nigeria

1980, 2000, 2020

Reprinted from www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb.

Slide 14

A later stage of demographic transition: population pyramids for Indonesia

1980, 2000, 2020

Reprinted from www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb.

Indonesia has a much more “mature” population pyramid than Nigeria

Slide 15

The final stage of demographic transition: population pyramids for the United States

1980, 2000, 2020

Reprinted from www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb.

The population “ages”, with continued echoes of the post-WWII baby boom

Slide 16

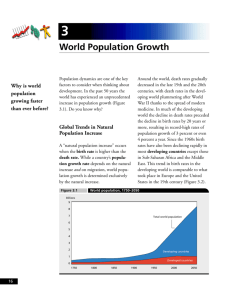

The lower-income regions have had a later

(and much faster!) demographic transition

Slide 17

Africa’s pop. growth has been of unprecedented speed and duration, but is now slowing

Slide 18

Africa’s child dependency has been similarly unprecedented, and is now improving

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

E. Asia S. Asia Sub-Sah. Africa Whole World

Source: UN Population Division, World Population Prospects:

The 2000 Revision (http://esa.un.org/unpp)

Slide 19

Explaining the demographic transition

What can account for the patterns we’ve seen, including especially the late and rapid demographic growth and child dependency in poor regions?

Will look first at mortality decline, then fertility decline…

Slide 20

Explaining the mortality decline (UK data)

General improvements in: overall well-being education female literacy diet, water and sanitation

Not, medical breakthroughs…!

Slide 21

Explaining the mortality decline (US data)

Slide 22

The age structure of mortality decline

Slide 23

The HIV/AIDS tragedy

Slide 24

Explaining the fertility decline: social policies

Source: K. Sundstrom. “Can governments influence population growth?”

OECD Observer, December 2001, p. 35.

Slide 25

Explaining the fertility decline: infant mortality

The fertility decline lags substantially the drop in IM

Slide 26

Conclusions on population growth and the demographic transition

• Much popular understanding about population growth turns out to be wrong.

• In fact, over time and across countries:

– population growth starts with a fall in child mortality, which raises population growth because a fertility decline happens later

– the temporary burst of population growth involves a rise and then fall in the fraction of people who are children

– these changes are similar in all countries, but in today’s poor countries they occurred later and faster, with larger magnitude over shorter time period than occurred historically elsewhere

• How does demographic transition affect agriculture?

Slide 27

What happens to the number of farmers?

What happens to the number of farmers?

• Initially, farmers are much poorer than non-farmers

– less capital/worker, lower skills, less specialized this means agriculture is the “residual” employer…

(what is the opportunity cost of labor?)

The annual change in the number of farmers depends on: growth in the total population growth in nonfarm employment

Slide 29

Some arithmetic of structural transformation

If we divide the total workforce into farmers and nonfarmers:

L f

= L t

– L n

( L i

=no. of workers in sector i)

And solve for the growth rate of the number of farmers as a function of growth in total and non-farm employment, we see that size of the sectors matters a lot:

%

L f

= ( %

L t

– [ %

L n

• S n

]) / ( S f

) ( S i

=share of workers in i)

In poor countries, even if non-farm employment grows much faster than the total workforce, the number of farmers may still rise quickly:

Rate of growth in rural population, by relative size of the sector proportion of workers who are farmers (

S f

):

Country is poor but successful: nonfarm employment growth

( %

L twice rate of workforce growth

( %

n

)

=6%,

L t

) = 3%

3/4 2/3 half

+2.0% +1.5% 0.0%

Slide 30

The number of farmers rises then falls… until farmers’ incomes catch up to nonfarm earnings

The “textbook” picture of structural transformation within agriculture: farm numbers stabilized by off-farm income and rising profits per acre; latest census shows slight rise in no. of farms

Figure 5-3. Number and average size of farms in the United States, 1900-2002.

Slide 31

In very rich countries, the number of farmers does not keep falling to zero!

• In an economics model of occupational choice, farmers would move to nonfarm work if it offers higher incomes;

– recall the “Harris-Todaro” story…

• An equilibrium at which the number of farmers stays constant would offer equal farm and nonfarm earnings:

Wage off-farm

= Earnings on-farm

= Profits/acre x acres/hour

– Thus, you can have no change in the number of farmers

IF

• profits/acre or

• acres/hour rise fast enough to keep up with off-farm wages

Slide 32

In the world as a whole, the number of farmers has just peaked and will soon decline

Slide 33

Regions differ sharply in their population growth rates

Source: Calculated from FAOStat data (www.fao.org).

Slide 34

Cities are growing much faster than total population

Source: Calculated from FAOStat data (www.fao.org).

Slide 35

…but cities are still too small to absorb all population growth, especially in S. Asia and Africa

Source: Reprinted from W.A. Masters, 2005. “Paying for Prosperity: How and Why to Invest in

Agricultural R&D in Africa.” Journal of International Affairs 58(2): 35-64.

Slide 36

Conclusions on economic growth and structural transformation

As incomes grow…

(1) Farming declines as a fraction of the economy

• in favor of industry and services

• even within agriculture

(2) Farmers’ incomes at first decline relative to others

• but then farm incomes catch up…

• until farm incomes equal or pass non-farm incomes

(3) The number of farmers first rises and then falls

• speed depends on both population and income growth

• eventually the number of farmers stabilizes

• in the future, the number may even rise!

Slide 37

More conclusions…

• Demographic transition and structural transformation interact, causing a rise & then fall in the number of farmers

• Today’s developing countries have had very fast decline in death rates, leading to unprecedented speed of change;

• With small shares of the population in nonfarm employment, this led to unprecedented rural population growth and declines in land available per farmer.

• The rural effect is compounded by shift in age structure:

• first, more children/adult (the “demographic burden”),

• then, more child-bearing women (“population momentum”),

• then more working-age adults (the “demographic gift”)

• These are powerful drivers of change in agriculture and in agricultural policy, but occur slowly and are often ignored!

Slide 38