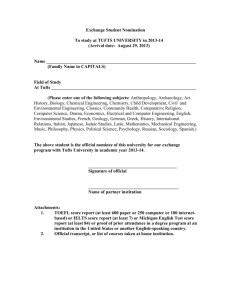

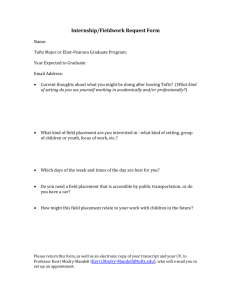

here - Tufts University

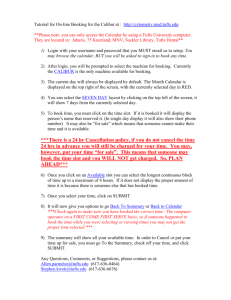

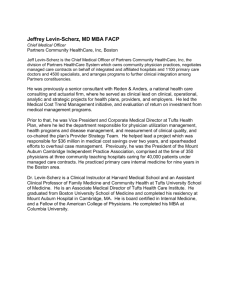

advertisement