"Presidebilismo" In South America - Illinois State University Websites

advertisement

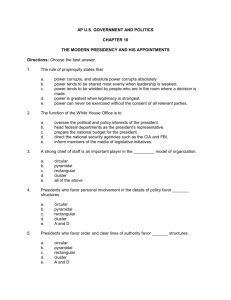

“PRESIDEBILISMO” IN SOUTH AMERICA: THE ARGENTINEAN CASE Christopher A. Martinez Loyola University Chicago Abstract: In the last 27 years, seventeen presidents throughout the world have not been able to complete their constitutional term in office. But more surprisingly, twelve of them took place in South America where presidents enjoy strong formal powers. This is the paradox of presidebilismo: presidents facing high risk of early departure from office in countries where they are endowed with strong constitutional powers vis-à-vis the legislature1. By using a path dependent approach, I look at four presidencies in Argentina from 1983 until 2001 to examine the phenomenon of presidebilismo. I analyze the two ill-fated administrations of Raul Alfonsín (1983-1989) and Fernando de la Rúa (1999-2001), and also include Carlos Menem’s administrations (1989-1995 and 1995-1999), who completed two terms in office. Findings suggest that executivelegislative relations and economic conditions act as major structural determinants of presidebilismo, while mass mobilization works as a “precipitant.” Alfonsín and De la Rúa’s early departures were explained by the combination of minority government and serious economic woes. In turn, Menem’s first term represents the opposite: a not-threatening political and economic environment that enabled him even to seek reelection. Menem’s second period shows how a majority government canceled out the effects of a worsening economy and social protests allowing him to stay in office. 1 I want to thank to Dr. Peter Sanchez (Pol. Science Dept. at Loyola University Chicago) who came up with the term presidebilismo, which combines two Spanish words “presidencialismo” (presidentialism) and “débil” (weak). 1 Keywords: presidentialism - presidential breakdown – Argentina – executive-legislative relations I) Introduction South American countries have enjoyed stable and uninterrupted democracies in the last 20 years. While the democratic transition stage appears to be completed, democratic consolidation still requires more attention. Democratic stability, therefore, cannot be automatically interpreted as government stability. Indeed, several presidents have been removed from office or have prematurely ended their term. In the last 27 years, twelve out of seventeen presidential breakdowns throughout the world have taken place in South America. While some South American presidents have been overthrown by military means, others have voluntarily resigned or been removed by institutional mechanisms. This is a unique phenomenon especially considering that South American countries have historically been characterized by giving strong constitutional powers to the president vis-à-vis the legislature. In fact, one key feature of Latin American political systems has been presidencialismo, or the overbearing power of the chief executive vis-à-vis the legislatures and courts. We are thus left with the puzzle of why it is that many presidents have not been able to complete their term in office in several South American countries? This phenomenon can be depicted as presidebilismo: presidents facing high risks of presidential breakdown even though they are endowed with strong formal powers. Hence, the objective of this paper is to explain which factors drive presidebilismo. In the following section I will review the literature on presidential failures by looking at the three major determinants: institutional, economic, and social. In addition, I will describe how these different approaches explain presidebilismo. Section III addresses 2 the operationalization of the explanatory model that I propose; the conceptualization of the study’s variables, the selection of cases, and the method I will employ. In section IV, I will analyze the presidencies of the cases that I selected by looking at how executivelegislative relations, economic conditions, and mass mobilizations interact to affect presidebilismo. In the final part of this work, I present the conclusions, limitations and needs for further research. II) Literature review: the causes of Presidebilismo Even though the premature termination of a presidency is not a recent phenomenon, the scholarship has only recently started to address this phenomenon. Most of these works have focused on the causes or processes that led to such outcomes, the different types of premature presidential endings, and their consequences. Whereas some research has looked at the problem of presidential instability from a broader perspective, including countries from more than one geographical region (Baumgartner and Kada 2003; Kim and Bahry 2008; Pérez-Liñán, 2007); others have paid closer attention to Latin America and South America due to their high number of interrupted presidencies (Hochstetler 2006; Hochstetler and Edward, 2009; Llanos and Marsteintredet 2010; Negretto 2006; Valenzuela 2004). Institutional determinants The issue of presidential breakdown has been related to the so-called inherent instability of presidential regimes (Alvarez and Marsteintredet 2010). In comparing presidential and parliamentary regimes, Linz (1990, 65) argues that even when both systems face executive crisis, in parliamentary systems this would become a “government crisis,” whereas in presidential systems this would constitute “regime crisis.” This is due to the dual democratic legitimacy in presidential systems, where the president (who is, simultaneously, head of government and the state) and the legislature 3 are popularly elected for fixed and independent terms (Linz 1994, 6). Linz (1994) provides several examples where executive crisis in Latin American countries later on turned out to become regime crisis during the 1960s and 1970s. According to Linz (1994, 7), times when executives and legislatures are deadlocked can be especially “complex and threatening” in presidential systems for there is no democratic principle or rule that can solve such a conflict. Kim and Bahry’s (2008) work on interrupted presidencies in third wave democracies shows that divided governments, where the legislature is controlled by different parties or coalitions from the executive; low first-round vote share; and party fragmentation increase the odds of the president’s resignation or removal. Mustapic (2010) points to the congress as the key institutional feature of presidential democracy. She argues that the legislatures would allow for institutional resolution of government crisis similar to what the legislative branch does in parliamentary systems. Indeed, Llanos and Marsteintredet (2010, 216-220) state that legislative action stands as the “main force” driving a presidency’s premature end, which might be derived from a president’s low share of votes in the legislature. Negretto’s (2006) findings show that minority governments increase the likelihood of presidential breakdown. Nonetheless, Cheibub’s (2002) research on presidential democracies shows that presidentialism is neither related to deadlocks, minority governments, nor conflicts; thus, presidential breakdowns would not be affected by these factors. Pérez-Liñán (2007) states that presidents need a “legislative shield” to protect them from social mobilization. This “shield” requires support from a sufficient share of members of the legislature, which in turns requires cohesive and disciplined parties. Valenzuela (1994, 12) argues that Latin American presidents are especially weak and constantly threatened by the existence of “fragmented parties with little or no internal discipline.” He also adds that, under minority governments, presidents usually experience 4 serious problems in generating “legislative support,” even from his/her own party (Valenzuela 2004, 12). Indeed, in presidential regimes there seems to be a lack of incentives for executive-party cooperation. This is so since e.g. opposition’s politicians see strong presidents as threatening to their own interests, and they also would rather avoid relations with weak presidents (Valenzuela 2004, 13). Mustapic (2010, 23) explains that in a two-party system it is less likely that presidents would be backed up by the legislature, since the opposition has no major incentives for sharing the “costs of the crisis with the government party.” Mainwaring and Shugart’s (1997) work brings up more nuances to the discussion of institutional variables by assessing the interaction between party system and presidentialism during times of crisis. They find that the interaction between presidentialism and party system also affects the level stability/consolidation of democracy, where fragmented party systems and undisciplined parties make the system more unstable. In addition, several researchers have shown the difficulty for holding long-lasting party coalitions in presidential regimes (Amorim Neto 2006; Deheza 1998; Thibaut 1998). However, this does not mean that long-lived coalitions are not possible in presidential systems. For example, Chile and Brazil have enjoyed successful coalitions since both returned to democracy (Llanos and Marsteintredet 2010). These coalitions may be possible since coalitions in presidential regimes work under two different dynamics. Lijphart (1999, 105) explains that presidential regimes are by definition minimal winning coalitions when it comes to the presidency; but they also can be minimal winning, oversized, or minority cabinets with regards to legislative support. Economic factors Others scholars have stressed the role of economic performance on presidential breakdowns (Alvarez and Marsteintredet 2010; Hochstetler 2006; Kim and Bahry 2008; Llanos and 5 Marsteintredet, 2010; Negretto 2006). Presidential stability might be threatened by high rates of inflation or slow economic growth. For instance, Llanos and Marsteintredet (2010, 220) find that economic growth proved to have a significant effect on presidential breakdowns. They also show that a common feature of most interrupted presidencies has been economic mismanagement by the government, something with which Hochstetler and Edward (2009) agree. Kim and Bahry (2008) show that a poor economic performance increases the likelihood of presidents “leaving office early.” Negretto (2006, 87) complements this argument by claiming that a premature presidential term usually takes place amid social mobilization triggered by “unpopular economic policies.” In addition, Alvarez and Marsteintredet (2010, 49) posit that both democratic and presidential breakdowns share some basic determinants, e.g., economic performance and social mobilization. It is worth noting Przeworski and Limongi’s (1997) findings about the relationship between economic development and democratization. They find that countries with a declining economy and with a per capita income between $1,000 and $2,000 face more troubles when it comes to democracy’s survival than countries with $1,000 or less but with a growing economy (Przeworski and Limongi 1997, 177). This might help to understand the challenges that South American states may face when it comes to presidential instability. However, even though democratic and presidential breakdowns may share some common causes, their outcomes are fairly different. For instance, in South America after 1978 all presidential breakdowns have been followed by civilian governments, not military governments (Hochstetler 2006). Likewise, Alvarez and Marsteintredet (2010) point out that, even when presidential regimes are unstable, in the last decades this instability has not translated into a regime failure, but rather into a government crisis. Social mobilization: 6 A final factor driving presidential instability is social mobilization (Hochstetler 2006; Hochstetler and Edwards 2009; Kim and Bahry 2008; Llanos and Marsteintredet 2010). People on the street demanding the president’s ouster has usually been triggered by political scandals and poor economic performance. Hochstetler (2006) argues that social movements affect presidential stability especially when linked with legislative actions. Hochstetler (2006, 409) defines this as a “mutually reinforcing collaborative action” that has been able to successfully depose presidents from office in South America. She also claims that when institutional means have not found people’s support, motions for removing presidents have not worked out; however, social mobilizations on their own have often turned out successful. Kim and Bahry (2008) support Hochstetler’s findings, and also point out the importance of social mobilization. Kim and Bahry (2008) even state that in Latin America social mobilizations have stronger effects on presidential stability when compared with African countries. Additionally, Hochstetler and Edwards (2009) show that high levels of perception of corruption and the number of deaths as a result of government repression against protesters have a significant effect on explaining the failure/success of challenges to presidents. III) Research Design The Model: two structural determinants and one precipitant The major factors affecting presidential breakdowns identified in the literature are institutional, which mainly stress the executive-legislative relationships. Among non-institutional factors are mass mobilization, poor economic performance, scandals in which the president has been directly involved, and the number of dead protesters. The relationship among these factors can be understood either by following the explanations by Llanos and Marsteintredet (2010); or by Hochstetler and Edwards (2009), and 7 Kim and Bahry (2008). On the one hand, the role of executivelegislative relations becomes more relevant for explaining the final outcome. The existence of a unified, majority opposition may be sufficient to depose a president from office when political and/or economic crisis take place, regardless of the presence or strength of mass mobilization. According to Hochstetler (2006), and Kim and Bahry (2008), however, after political scandals or economic crisis takes place, a president’s survival hinges on the degree of social mobilization. Legislative action and street protests may support each other for the purpose of deposing a president. Although, it may be possible that mass mobilizations on their own can bring down a chief executive. At Figure 1, we can see a potential causal diagram for presidential breakdown. Under minority government situations the opposition might be even less likely to support the government and share the responsibility about political costs derived from economic crisis and street protests’ repression. Figure 1: Causal paths and interactions of Presidebilismo’s determinants Poor Economic Performance Scandals Minority government Presidebilismo Mass Mobilization The diagram shows that under poor economic conditions or high political scandals that involve the executive, presidents would be at risk if his/her party or coalition does not have a majority in the legislature and if this is accompanied by social mobilizations. In addition, it is important to note that there is a closer relation between economic crisis/scandals and mass mobilization than with minority government. Mass mobilizations usually arise in response to poor economic conditions. For instance, Corrrales (2002, 37) posits that in 8 less stable democracies when the economy performs poorly, people mobilize in order to protest against the government and politicians that (they believe) are corrupt, while exhibiting strong “antiestablishment sentiments.” Mass mobilizations then are the last visual reaction of economic crises. Leaving out political scandals, street protests seem unlikely to appear under good economic conditions. Thus, an economic crisis becomes a necessary condition for the upsurge of mass mobilizations, which can in turn affect the severity and length of the crisis. Minority governments, on the other hand are not necessarily a consequence of economic crisis. It is true that a ruling party or a coalition may be electorally punished for its economic mismanagement, but that would not be the only determinant of a minority government. Intra-party struggles, coalition breakdowns, ideological confrontations, a government’s inability to deliver electoral promises, executives that do not compromise with other parties, and electoral rules are some of the possible reasons for the existence of a minority governments. Whereas economic crisis and mass mobilizations are closely related; economic crisis and minority governments work under different dynamics. Therefore, the model that I propose will look at the likelihood of presidebilismo by focusing on economic conditions and the existence of a minority government. Yet, this model implies that more and stronger street protests will result as the severity of an economic crisis increases. Mass mobilizations are understood as “precipitants” or “triggers” of presidential early departure, which may speed up presidential removal. As Figure 2 shows, the prospect for a president’s survival is lowest under poor economic conditions and minority government; whereas it is highest when the economy does well and the executive’s party has a majority of seats in the legislature. The interaction between economic crisis and minority government sets the scenario within which non-governmental political actors will 9 become active. For example, civil society, student organizations, and unions may become relevant actors under these structural conditions. Figure 2: Interaction Economic Situation, Minority Government and Presidential Ouster Risk High Presidential Ouster Risk Bad Good Economic Situation Majority Government Minority Government Figure 3 shows how the two structural determinants interact Low may increase or reduce presidential and how these interactions survival. For instance, when both structural conditions are met, in quadrant C, prospects for presidential survival are at the minimum; whereas in quadrant B, where neither structural condition exist, the elected president has the highest chances to remain in office. However, when only one structural condition exists, in the quadrants A or D, they will tend to offset each other, raising the probability that the president will complete his/her constitutional term as expected. Consequently, I propose the following working hypotheses: H1: Presidential ouster risk will be the highest under economic crisis and minority government. H2: Presidential ouster risk will be the lowest under good economic conditions and when the president’s party or coalition controls the legislature. H3: During economic crisis the president may survive in power as far as s/he enjoys a majority government. H4: The president may finish his/her constitutional term in office under a minority government if there is no economic crisis. Figure 3: Four Scenarios for President Survival as results of Economic Conditions/Executive-Legislative Relations Interactions 10 Majority government A B I C D G Exe-Leg Bad L H Good Economic Situation Operationalizing Presidebilismo:LThe case of Argentina B Minority government L Drawing on previous works (Cheibub 2002; Hochstetler i 2006; Kim and Bahry 2008; Negretto 2006), I define the concept of presidebilismo as a political crisis where a president, who ghas been popularly elected in competitive elections, is forced to leave h office early by means of impeachment, legislative initiatives, or resignation. Presidebilismo describes the situation where presidents are unable to fulfill his/her constitutionally term in office but without compromising the democratic order. What distinguishes the concept of presidebilismo from other concepts such as “interrupted presidencies” or “presidential breakdowns” is that in the former the presidential ouster is not an outcome of the use of force or its threat thereof by either the armed or police forces of the country. From a methodological stand, most works on this topic suffer from the problem of limited variance in the dependent variable; that is, only studying cases that have experienced presidential breakdowns. The only exceptions are Hochstetler (2006), and Hochstetler and Edwards (2009) who have allowed for some degree of variation on the dependent variables by focusing on “challenges” to presidents, which means that even if the attempt to remove the president fails, it is included in the analysis. Most works addressing this phenomenon have used cross-national and time-series quantitative analysis; thus, there is a need for bringing more methodological diversity that can improve our understanding of causal mechanisms. 11 The quantitative-leaning tendency for addressing this topic has overlooked how the independent variables interact to impact on the dependent variable. Simple correlations found in quantitative works do not provide sufficient information whether the timing when independent variables take place matters or not. I will adopt a path dependence method in order to comprehend how certain events may affect events that take place at a later time (Mahoney and Villegas 2006, 78). This is important since, for example, the effects of policies or plans launched by one administration may still have far reaching effects into the future, enhancing or threatening the stability of incoming administrations. The same is true about economic conditions: the range of maneuver of a newly elected president would be conditioned by how the economy was and is doing when s/he takes office. And, an election that results in a minority government will undoubtedly affect a president’s ability to stay in office, especially if the economy sours and people take to the streets. In addition, due to the “useful variation” of presidebilismo is rare, a case-study approach offers more opportunities for uncovering causal mechanisms than medium or large N studies (Gerring 2006, 111). Even with the lack of generalizability, case studies can provide significant insights about precise causal mechanisms. In fact, the real number of cases of presidebilismo is not very high, so a mid-N study can address a significant number of the total number of cases. Therefore, using a path dependent method and a case-study approach, this paper attempts to empirically analyze how the main variables discussed in the literature review -executive.-legislative relations, social mobilization, and economic crisis- affect the likelihood of presidebilismo’s occurrence. Why Argentina? Most presidential breakdowns in the world have taken place in South America, specifically, in seven countries. In fact, three 12 countries have experienced the majority of interrupted presidencies. In Argentina, Bolivia and Ecuador presidents have failed to finish their constitutional terms in office more than once in the last 30 years. Unlike Ecuador and Bolivia, Argentinean presidents have not been deposed by indigenous mobilizations or military interventions. Argentina represents a special case due to its homogeneous population and high level of democracy and economic development in comparison with Bolivia and Ecuador. Rather, economic crisis, union-led street protests, and institutional arrangement have been more important in explaining Argentinean presidebilismo. From the 1990s on, Argentina could rule out military influence on politics and also was able to become in one of the most prosperous developing countries in the world. Notwithstanding the ouster of two presidents, the Argentinean democratic regime has not been threatened. The Argentinean case also enables us to look closer at how economic conditions and social mobilization combine with institutional arrangements to affect presidential survival. As described in the previous section, the scholarship is divided among those who regard the executive-legislative relations as the main determinant of presidential stability; those who stress social mobilization; and those who focus on both factors. Argentinean “presidebilismo” will be addressed by looking at the country’s two deposed presidents, Raul Alfonsín (1983-1989) and Fernando de la Rúa (1999-2001), who were popularly elected in competitive elections. There were other Argentinean presidents who were ousted from power as well (Adolfo Rodríguez Saá and Eduardo Duhalde); but since they were appointed by Congress after De la Rúa’s failure, they are not included in this study. In addition to Alfonsín and De la Rúa's administrations, I will analyze Menem’s two terms in office (1989-1995 and 1995-1999). I do this to add more variation to the dependent variable “presidential stability.” Menem’s administration will serve to see whether the same factors that affected Alfonsín and De la Rúa ouster were present during his successful terms in office. 13 Information about social protests is collected from Schuster’s et al (2006) work that covers mass mobilizations in Argentina from 1989 until 2003. Although, data for Alfonsín’s entire administration are not available, there is sufficient data for the period just prior to Alfonsín resignation. In addition, I will use printed press information to complement Schuster’s et al. (2006) data. Economic crisis information is gathered from the World Bank data series. In order to identify periods of economic downturns I look at the following variables: GDP per capita, inflation rates, GDP growth, external debt, and unemployment. All these data serve to compare the different economic situations that the three presidents experienced. Information about election results and legislative o congressional party composition has been obtained from the Argentinean Ministerio del Interior (Ministry of Internal Affairs. To complement this data, I also refer to secondary data sources such as research articles published in scientific journals that address the executive-legislative relations in Argentina. IV) Data Analysis Raul Alfonsín’s Presidency (1983-1989): After several years under a military regime, Raul Alfonsín took office in Argentina with the major goal of consolidating the transition to democracy. He received an absolute majority of the votes and became the first president from the Radical Party to win a free and fair election since the 1940s. This electoral victory also translated into the Chamber of Deputies where the Union Cívica Radical (UCR, Radical Civic Union) obtained a slight majority of seats (50.8%). However, Alfonsín’s party was not able to control the Senate, where the UCR only got 39.1% of the seats, while the major opposition party, the Partido Justicialista (PJ), held 45.7% of the seats. Moreover, the PJ also won the majority of governorships, 54.5% 14 versus 31.8% of the UCR. Hence, from the very beginning, Alfonsín suffered from a minority government. It is worth noting that Argentinean parties are characterized by weak party cohesion. Mustapic (2002, 27-28) states that there are two major factors causing this: low ideological density and decentralized structure (national, provincial, and local). The party leader then relies mostly on his/her electoral potential (Mustapic 2000, 580). Mustapic (2000) argues that winning elections becomes the decisive factor for obtaining party unity and cohesion, which hinges around its successful leaders. Cheresky (1990, 54) even claims that when Alfonsín ran for the presidency, he represented a minority faction within the UCR; but he at least could count on strong public support. Thus, Alfonsín led a minority government and a not-always reliable party support, with no more tools than his “electoral success” and public support. The minority government situation meant that the Radicals were not able to pass important legislation. Greater interparty cooperation was hard to achieve given the internal struggles over the PJ’s leadership as a result of its electoral defeat in 1983 (Cheresky 1990, 57). The historically close relationship between the PJ and the sindicatos (unions) became evident during this period when the Central General de Trabajadores (CGT, the General Workers Central) and its leader, the moderate Peronist Saul Ubaldini, represented the “real” opposition to the Alfonsín administration (ibid.). Indeed, the role of the CGT in opposing Alfonsín was also significant for putting people on the streets by organizing more than 13 general strikes (ibid.) As soon as he took office, Alfonsín also had to deal with harsh economic conditions inherited from the military government: an inefficient and oversized bureaucracy (Llanos, 2010, p. 58); two consecutive years with negative economic growth (1981=-5.7%, and 1982= -5.0%); an external debt that had increased more than five times in the last seven years (Andreassi 2011), and hyperinflation 15 (344% in 1983). In 1985, with the situation not improving, one of the first major strikes occurred. The CGT and Ubaldini were able to gather around 200,000 people to protest the economic situation and to ask for Alfonsín’s resignation (Montalbano 1985). The government implemented the Austral Plan in an effort to minimize the effects of the economic crisis and to calm social mobilizations. The plan was very peculiar for it aimed to control inflation but simultaneously to maintain the current low unemployment rates and economic growth (Llanos, 2010, p. 58). The underlying idea of the plan was to avoid negative consequences on people in order to not put the democratic transition at risk (ibid.). The short term effects of Plan Austral were positive though. The GDP grew dramatically from 7.59% in 1985 to 7.88% in 1986; while inflation dropped from 672% to 90% in the same period (World Bank, 2011). The immediate effects of Plan Austral were to avert a political crisis for Alfonsín. The first mid-term election turned out positive for Alfonsín’s government. Whereas the UCR kept its share of seats in the lower house, the Partido Justicialista lost almost 5% of its seats. Notwithstanding the PJ’s electoral defeat, nothing changed in terms of Congressional majorities: the UCR kept control of the lower house, while the PJ dominated/controlled the Senate. At the end of 1986, Plan Austral’s positive effects proved to be ephemeral. The economic situation became even worse. The economy decreased and inflation increased, plus the business sector and unions started to exert pressure over Alfonsín’s government (Llanos 2010, 59). In response, the government launched the Plan Primavera (Spring Plan) in August of 1987. Yet, it was too late for increasing the UCR’s popularity. The second mid-term elections held in September of 1987 left the government in a weaker position. The consequences of the 1987-elections were important. First, the PJ got 74.3% of the governorships (a 22.8% increase), whereas the UCR was able to retain only three out of 22 governors (in Cordoba, Rio Negro, and the Federal District). Second, even though the PJ slightly increased its share of seats in the Chamber of Deputies (from 40.6% 16 to 41.7%), the UCR’s share of seats declined to 44.7%, losing the majority in the lower house and becoming the first minority party. Third, the chances of a constitutional reform that would allow Alfonsín to be reelected finally vanished (Llanos, 2010, p. 59). At this point, the extreme scenarios described in the previous sections – minority government and economic crisis with social mobilization - were about to meet and combine. In this new and more adversarial political scenario, Alfonsín’s options were drastically reduced. The minority government situation, in which his party at least controlled the Chamber of Deputies, had come to an end. Now, the executive faced a “no majority” situation in Congress (Negretto 2006, 84). The economic woes resembled what happened in 1985, but in 1989 Alfonsín had fewer political resources to rely on. For instance, Alfonsín was not able to increase public spending since bills on tax increases and privatizations were not approved in Congress (Llanos 2010, 60). Furthermore, the economic crisis in 1989 was even worse than the one in 1985. The dollar went up and reserves were almost exhausted (Llanos 2010, 60); the GDP per capita declined from $3,977 in 1988 to $2,380 in 1989; two years of negative economic growth (-2.6% in 1988, and -7.5% in 1989); and inflation skyrocketed, reaching almost 40% monthly in the first semester of 1989. The only missing element was civic action, that is, the social and political actors that will take advantage of the two interacting structural conditions. The number of street protests went up to almost 300 in the first six months of 1989, one of the highest levels in Argentina’s recent history (Schuster et al. 2006, 30). Unions organized 71% of the street mobilizations, and only a 13% of them were led by neighbors and students (Schuster et al. 2006, 36). This high level social mobilization created a political opening for the opposition. The Partido Justicialista could benefit greatly from the sindicatos’ actions by weakening Alfonsín’s government and also the Radical candidate who was running for the presidency in 1989. In fact, Llanos (2010, 61) points out that Peronist right-wings factions 17 might have instigated the looting that later on took place in May 1989. The economic crisis, social mobilizations, and the institutional paralysis resulted in a serious political crisis: the resignation of Alfonsín’s economic minister and his team in March 1989 (Llanos 2010, 60). The appointment of a new economic minister did not bring more consensus as expected, and eventually the Peronist candidate, Carlos Menem, won the presidential election in May 1989. The increasing street protests, looting, and violence that left 15 people dead, set in motion Alfonsín’s early departure from office. Alfonsín started negotiations with the elected president, Carlos Menem, so as to agree on the terms of the anticipated handover. Menem finally accepted Alfonsín’s offer and also secured the approval of economic legislation in the lower house, where the Radicals were the first majority party, until the new Congressional elections in December 1989 (Llanos 2010, 61). Alfonsín resigned on June 12th (five months early) during one of the most severe economic, social and political crises that Argentina had experienced in 30 years. Even though Alfonsín led a minority government (from 1987 to 1989 he was under a divided government) and faced poor economic conditions, his survival in office was only at risk when major social protests arose. Yet, it is important to note that the harshness of the economic woes was partially overcome by the Austral and Primavera plans. Still, their effects were short-lived. Alfonsín’s party losing its legislative majority and the economic crisis worsening finally coalesced in 1989. Mass mobilizations took place, demanding better salaries and a lower inflation, which put the government in a weak position. When the president leads a minority government, it is not only that the congress cannot provide a “legislative shield” to deal with social mobilizations; but the legislature might even leave the president with no political support, making it difficult to survive a serious political and economic crisis. 18 In this case, not having a majority government, along with the severe economic crisis and resultant social mobilization, led Alfonsín to voluntarily leave the presidency before his constitutional term was over. Carlos Menem’s Presidency (1989-1999) Even though Menem took office amid the worst hyperinflationary crisis since Argentina returned to democracy in 1983, the president could rely on the electoral support he received in the 1989 election, and also on the idea that the early start of his presidency was necessary to save the economy. Furthermore, Menem was also counting on the Justicialista majority in the Senate (56.5%) and governorships (77.3%). However, the PJ did not control the Chamber of Deputies where it became the first minority party (44.1%) after the Congressional elections held on December 1989. In turn, the UCR share of seats kept falling. In the lower house, the UCR controlled only 35.4% of seats and 30.4% in the Senate. Therefore, even though the economic situation might threaten Menem’s government, he could still count on the “legislative shield,” and most importantly he had ensured that major economic reform would be backed by the opposition. Menem definitely had more political and institutional resources to use at the start of his administration than Alfonsín did during his whole term. Yet, executive-legislative relations were not as smooth as expected owing to congress’s composition. Ferreira and Goretti (1998, 35) state that Menem faced opposition in Congress especially after he started to issue decrees of necessity and urgency (DNUs). His argument rested upon the need for speeding up law-making as the situation required (ibid.). Nevertheless, the DNUs approval required judicial revision, and since the Supreme Court’s members were appointed under Alfonsín’s administration, Menem was not able to ask for their removal. Instead, what he did was to pass a “packing plan” in the Senate, where the PJ had an overwhelming majority, so 19 as to increase the number of members of the Supreme Court (Ferreira and Goretti 1998, 36). In doing so, Menem paved the road for issuing DNUs even during times of neither necessity nor urgency. In his first term in office, Menem used 336 DNUs compared with 25 that had been issued between 1853 and 1989 (Ferreira and Goretti 1998, 33). The goal of consolidating the democratic transition that characterized Alfonsín’s government was of secondary importance for Menem and citizens, principally because of the declining economy. Even though Menem was elected on the basis of his populist promises of salariazo (increasing salaries), as soon as he took office, he carried out the most extensive neoliberal reform package ever implemented in Argentina. In August 1989, Menem, supported by the Radicals, enacted the State Reform Law, which basically allowed for the privatization of most state assets (Ministerio del Interior de Argentina 2008, 157-158). People came to believe that state intervention in the economy was responsible for the egregious economic outcomes of the Austral and Primavera plans (Ferreira and Goretti 1998, 38). Consequently, when Menem took office, people were much more concerned with reducing inflation and the state’s role in the economy (ibid.). These demands were incorporated by Menem when adopting several market-oriented policies, such as deregulation, privatization, and the reduction of government spending. These steps were taken because of the increasing concentration of power in the executive branch (owing to the DNUs), the Delegation Act authorized by Congress (controlled by the Justicialistas), the “packing plan,” and the constant request by citizens for fast solutions (ibid.). In 1991, the economic situation significantly improved. The GDP per capita went up to $5,733 (2,381 in 1989) being higher than at any point during Alfonsín’s administration; economic growth reached a historic double-digit number (12.67%)); and the major issue in the last decade, inflation, finally seemed to be under control (172% in 20 1991 compared with 3,080% in 1989). While large-scale privatizations were mostly responsible for increasing state revenues; the Convertibility Law, which pegged the peso to the dollar (one-to-one), was responsible for controlling the skyrocketing inflation. In 1994, the annual inflation rate was 4.2%, economic growth hinged around 6%, and the GDP per capita increased to $6,967. On the other hand, the unemployment rate, which historically had been low in Argentina (one digit), started to go up in 1994 (12.1%). Nevertheless, the period 1991-1994 did not witness a significant number of mass mobilizations (Schuster et al. 2006, 31). This may have been because people preferred low inflation rates over full employment, therefore, exhibiting “higher tolerance for recession” (Schamis 2002, 84). In electoral terms, the PJ strengthened its dominance in the Senate after the1992 mid-term elections by controlling 58.3% of seats. In 1993, the Justicialistas also achieved an almost absolute majority in the Chamber of Deputies (48.2%). With a near-majority in the Congress and the governorships, and an economy that finally took off, Menem’s stability in office was not under discussion. The two major structural determinants of presidebilismo provided a secured political, economic and social environment not only for Menem’s survival in office, but also for his reelection. In 1995, Menem was reelected thanks to the “Pact of Olivos,” between the PJ and formerpresident Alfonsín, as leader of the Radicals, which reformed the constitution in 1994. Menem’s second term began with the Justicialista’s electoral victory in the mid-term election held in 1995. The PJ obtained an absolute majority in both the lower house (51.4%) and the Senate (55.5%). The undesirable consequences of a minority government were gone. However, the economy started to exhibit some setbacks. The GDP per capita had stagnated just above $7,000; economic growth dropped to -2.5% in 1995; and unemployment reached 18.8%. State revenues from privatization proved not to be long-lasting. For instance, the privatization of the social security system began to 21 require more resources than the government possessed. The social security deficits led the government to a “spiral of borrowing” since as the public systems of social security had lost “contributors,” the government still had to deal with “beneficiaries” (Levitsky and Murillo 2003; Schamis 2002). Public finances became more limited at the same time that the executive had fewer policy tools to react under new economic woes. The Convertibility Law that had successfully wiped out inflation now appeared to be limited as a vehicle for economic stimulation. The Convertibility Law required that the Central Bank had to back all the Argentinean monetary base with international reserves, which meant that the government could inject money into the economy only when international reserves increased via “trade surpluses or net capital inflows” (Schamis 2002, 83). No mechanisms for economic stimulus remained under government control (Schamis 2002, 82). Basically, the Convertibility Law eliminated the possibility of the executive using monetary and exchange policies to counteract “economic shocks” (Levitsky and Murillo 2003, 153). Social mobilizations were not absent during Menem’s administration. Indeed, his government faced one of the largest number of street protests in the period 1989-2003. The rising unemployment and the declining economy were the driving forces for the protesters. In spite of the high number of street protests, especially in 1997, Menem’s survival in office was not affected. During that period, Menem’s party enjoyed a majority within Congress that served as a counterweight to the effects of street protests. It is worth noting, though, that the main difference between the mass mobilizations that took place under Alfonsín’s administration and Menem’s second administration was the source of their organization. Whereas 71% of the street protests under Alfonsín were organized by sindicatos; during Menem’s second term only 36% of them were union-led (Schuster et al. 2006, 38). 22 Coincidence or not, about 25% of Justicialista deputies were also labor leaders during the 1990s (Corrales 2002, 34). Internal struggles took place within the PJ when Menem announced that he was seeking a third presidential term. Despite the fact that a third term was unconstitutional and that 80% of the population opposed to it, Menem thought that as long as his party backed him, the Supreme Court would not be an issue (Corrales 2002, 33). Still, Justicialista leaders that considered Menem’s third term bid as a threat to their own political careers rejected Menem’s second reelection (Corrales 2002, 33). The PJ’s intra-party conflict manifested itself in a spending race, which led to a rising national debt (Corrales 2002, 32). As a matter of fact, in 1998 Argentina’s external debt was $75,524 million, a 45.7% increase from 1989. Menem’s populist message reemerged and, instead of cutting spending, he proposed to increase the 1998 budget (ibid.). Finally, the internal resistance against Menem’s desires for a third term was successful, deterring him from seeking a second consecutive reelection. Eduardo Duhalde, one of the strongest opponents to Menem’s third period, was chosen as the presidential candidate for the 1999 election. Whereas democratic principles prevailed; the fiscal irresponsibility of Menem and provincial authorities put the economy at risk, “increasing… [its] vulnerability to the external shock of 1998” (Corrales 2002, 34). Menem’s second term enables us to understand how the two structural determinants of presidebilismo –a minority government and economic woes- may affect a president’s prospects for survival. During Menem’s first term the presidential stability was not at stake even when inflation was not under control in 1989-1991. Legislative strength, the growing economy, and the lack of significant mass mobilization led Menem to his successful presidency and his subsequent reelection. The second term shows that even when one of the structural determinants turns out threatening to presidential stability the other can act as a counterweight. Although the economy 23 declined, Menem still had a majority in the legislature during his second term. Fernando de la Rúa’s Presidency (1999-2001) Fernando de la Rúa became the second Radical president, after Alfonsín. The successive electoral defeats suffered during the 1990s had weakened UCR’s popular support. Therefore, so as to defeat the PJ in the 1999 election, the UCR formed the “Alianza” (Alliance) with the newly created conglomeration “Frente Pais Solidario” (FREPASO, Country in Solidarity Front). The ideological diversity of FREPASO, composed by some leftist and former Peronistas groups, was mostly recognized by its two major leaders Carlos “Chacho” Alvarez and Graciela Fernandez Meijide (Llanos 2010, 62). The potential of the Alianza rested upon the combination of each partner’s strengths. FREPASO’s lack of well-developed internal rules and structure could be overcome by the UCR’s “national organizational structure” (Llanos and Margheritis 2006, 81). On the other hand, FREPASO’s leaders enjoyed broad popular support and media communication skills (ibid.), which were one the major flaws of the UCR. The Alianza promised an end to corruption, increased transparency, and increased investments in social sectors (Corrales 2002, 34), while keeping the Convertibility Plan, and improving “democratic governance mechanisms” (Llanos 2010, 62). The Alianza was successful since Fernando de la Rúa easily defeated the Justicialista candidate in the 1999 presidential election. The Alianza was the first coalition to take office in recent Argentinean history (Llanos and Margheritis 2006, 78). Still, the Alianza’s popular support did not translate into the Congress. Despite the Alianza’s advantage over the PJ (about 1% in the share of seats) in the lower house, it was able to control only 39.7% of the seats, becoming the first minority party. The PJ, in turn, had the majority in the Senate (55.5% of seats) and governorships (62.5%). Again, the 24 same unfavorable legislative situation faced by Alfonsín’s administration emerged in the De la Rúa government. Soon after taking office, the coalition started to evidence signs of divisions. De la Rúa’s relations with FREPASO became complicated since the president only gave secondary government positions to its leaders (Schamis 2002, 87). More surprisingly, De la Rúa excluded influential Radical leaders from his inner circle, which was formed by friends and family (e.g. his son and his brother) and only a few young Radicals who had little influence within the party (Llanos and Margheritis 2006; Schamis 2002). De la Rúa not only faced an unfavorable environment in Congress, but now he had also limited the political resources he might borrow from the two partners of the Alianza. Furthermore, the executive also had problems when negotiating with the opposition. Llanos and Margheritis (2006, 89) point out that the PJ was unwilling to cooperate with a “weak executive,” and then share the costs of adopting unpopular policies. The Justicialistas opposed De la Rúa’s bills in the Senate, especially those involving labor issues. In fact, the PJ was not willing to approve any labor reform under Menem’s administration. Nevertheless, De la Rúa achieved a twofold victory in this area. His bill on labor reform was finally approved, although resisted by his coalition fellows in the lower house, and then passed in the Senate, thus breaking the Peronista majority (Llanos and Margheritis 2006, 8990). This law became the major political victory of De la Rúa in a clearly unfavorable legislative context. Yet, the initial excitement was quickly replaced by concern. The Alianza became involved in a political scandal as the government was accused of bribing senators so as to get the labor reform law passed (Llanos and Margheritis 2006, 89-90). The Vice-President and FREPASO leader, Carlos “Chacho” Alvarez, requested an immediate investigation of the accusation. Since the government failed to investigate, in October 25 2000, Alvarez resigned, generating the first political crisis within the executive (Levitsky and Murillo 2003, 154). When De la Rúa took office the economy was already in trouble. In addition to De la Rúa’s political isolation, the country experienced high unemployment rates, negative economic growth, and an increasing external debt. Alvarez’s resignation did nothing but increase Argentina’s financial risk rate owing to fear of political and financial instability (Schamis 2002, 87). After this, the risk of financial default rose which made the situation for De la Rúa even worse (Llanos and Margheritis 2006, 93). The Convertibility Plan had already taken away the most important tools for dealing with economic crisis from the executive. De la Rúa attempted to address the economic woes via issuing DNUs and asking the Congress for discretionary power for his economy minister (Schamis 2002, 88). This not only did little to improve the economy, but also exacerbated De la Rúa’s political isolation (Llanos and Margheritis 2006, 91). External economic aid became urgent. However, external funds, specifically from the IMF, were conditioned, in effect prohibiting “counter-cyclical deficit spending” (Levitsky and Murillo 2003, 154). Consequently, De la Rúa was forced to implement unpopular austerity policies that restricted public spending to balancing the public deficit (Llanos and Margheritis 2006, 94). De la Rúa compromised with the IMF to lower the public deficit to zero and to negotiate a “debt swap” (Corrales 2002, 38). Both efforts did not work out. Owing to the De la Rúa’s broken relations with his party, his attempts to use tax revenues and spending cuts for lowering the public deficit failed in Congress (ibid.). Public opinion had started to harshly criticize De la Rúa’s decisions to adopt austerity policies. De la Rúa’s stated that he was committed “to pay the debt under all circumstances” (Schamis 2002, 82), which increased public discontent since the president seemed to be more worried about reducing the public debt than to satisfying people’s needs. 26 In 2001 the economy underwent its third consecutive year of negative growth, the unemployment rate was at a high level again (18.2%), and the external debt seemed to not have a ceiling ($82,994 million). To make things worse, in March 2001, the FREPASO leader, Graciela Fernandez Meijie, minister of social-welfare, also resigned (Schamis 2002, 87). De la Rúa’s weak political capital kept diminishing. As De la Rúa’s first electoral test approached, street protests began anew. The provinces were adversely affected by the economic downturn and executive financial mismanagement. Llanos (2010, 64) explains that the central government was not even able to deliver the “minimal monthly sum…of revenue-sharing tax scheme” to the provinces, unleashing popular outrage. As expected, De la Rúa’s government did not pass the mid-term elections test. The PJ won more seats in the lower house at the expense of the Alianza. The Justicialistas presented a stronger opposition to De la Rúa since there was no one willing to share the cost “with a government that everyone else had shunned” (Corrales 2002, 38). Executivelegislative’s prospects for cooperation were extremely unlikely. On one hand, there were widespread demands for injecting more government resources into the economy; on the other hand, the opposition-controlled Congress was unlikely to agree to cutting more than $4 billion in social spending and salaries in the 2002 budget (Krauss 2001). Moreover, the PJ even threatened De la Rua by using the Ley de Acefalia (so-called Acephaly Law), whereby the president of the Senate may take office when the elected president is declared “not able” (Llanos 2010, 64.) In November 2001, as a response to ongoing capital flight, the Economy Minister limited “bank withdrawals and currency movements” (Levitsky and Murillo 2003, 154-155). This policy, known as Corralito (financial corral), proved to be highly unpopular since it deprived people of their savings (ibid.). In December 2001, Corralito’s immediate consequences included people protesting on the streets, riots, looting, piqueteros (road blockers), eighteen people killed, and mass mobilizations across the country (Llanos 2010, 65). De la 27 Rúa declared a state of siege. On December 19th, the Economy Minister resigned, and so did the whole cabinet on the next day. De la Rúa’s last attempt to remain in office was to propose a “government of national unity” to the Justicialistas, which they rejected (Schamis 2002, 85). The reasons? Schamis (2002, 85) argues that when they took De la Rúa’s offer to the UCR leaders, the latter refused to “take part in any government [De la Rúa] might head.” After brutal police repressions against protesters in Buenos Aires, that left several dead, De la Rúa finally resigned on December 20th, 2001, in the middle of his constitutional term. Schamis (2002, 86) notes: “Fernando de la Rúa fell in precisely the same way he had governed: cut off from the larger political society, at odds with his own party, and surrounded by a clique of unelected, nonpartisan advisors, several of whom had no previous political experience of any kind.” After analyzing De la Rúa’s presidency, it is possible to attribute his presidential breakdown to the two structural determinants of presidebilismo along with street protests. A divided government, a broken economy, and few but very powerful mass mobilizations reduced the chances for De la Rúa to stay in office. Even though he inherited the adverse economic conditions from Menem’s irresponsible administration, De la Rúa also inherited a weak electoral and political legacy from the UCR. Nevertheless, the president himself wiped out the only few political alternatives when breaking relations, first, with FREPASO, and later with his own party. The street protests worked as expected, as the last element that finally led the president to his political demise. V) Conclusions The question what drives presidebilismo? has been partially answered. Executive-legislative relations and economic conditions are 28 the major determinants of presidential survival. The role of mass mobilization is influential mostly in the last part of the causal chain. Street protests tend to appear only once economic conditions have worsened and perhaps serve to accelerate the presidential ouster. Whereas executive-legislative relations and economic conditions act as major structural determinants of presidebilismo, mass mobilization works as a “precipitant” factor. The three cases described and analyzed enable us to understand how the factors that drive presidential stability interact and then how they might impact on the dependent variable. Under Alfonsín’s administration, economic crisis and minority government coincided only at the end of his administration. Only when the hyperinflation crisis took place did important street protests trigger Alfonsín’s anticipated departure from office. The case of Menem provides several examples of how the two structural determinants can offset each other. His first term was characterized by cooperative relations between the executive and the legislature. Even though Menem tended to act unilaterally, which somewhat antagonized the legislature, parties in Congress did not oppose his initiatives. He had enough time (2 years) to solve the inflationary crisis without being threatened even once. Menem’s second term offers more details about how presidential stability starts to weaken when either the legislative support or the economy fails. Still, Menem was able to remain in office, and was almost able to run for a second reelection. Finally, the case of De la Rúa best represents a “perfect storm” for presidential survival. Not only were economic woes present as soon as he took office, he never enjoyed legislative support. In addition, De la Rua contributed to his own ouster by giving up the only political resources that he had in Congress: the Alianza. Further research is needed so as to analyze the role of nonpartisan political actors and unions. Indeed, one common feature shared by the two non-Peronistas parties was their lack of influence on sindicatos (Corrales 2002, 34). Political leadership, especially in De la 29 Rúa’s administration, proved to play a major role in the relationship between the president and his own party/coalition. International forces also put pressure on and conditioned the set of policies available for presidents to deal with domestic economic crises. These three issues have been overlooked in the literature of presidential stability. Finally, from a methodological viewpoint, it is important to understand and take into account the historical sequence of events that help us to explain presidebilismo. For instance, without considering the fiscal irresponsibility and economic reforms that took place during Menem’s administration, it is not possible to comprehend why and how De la Rúa was so extremely conditioned when he took office; and also why and how Menem did not fall. Quantitative studies basically tend to assume that the political system, the economy, and people’s beliefs reboot every calendar year or with the start of a new government. This is where the strength of path dependence approach rests: in explaining how past events still can affect future outcomes. Reference Alvarez, Michael E., and Leiv Marsteintredet. 2010. “Presidential Democracies Breakdowns in Latin America: Similar Causes, Different Outcomes.” In Presidential Breakdowns in Latin America: Causes and Outcomes of Executive Instability in Developing Democracies, Eds. Maria Llanos and Leiv Marsteintredet. New York, NY: Palgrave McMillan. 30 Amorin Neto, Octavio. 2006. “The Presidential Calculus Executive Policy Making and Cabinet Formation in the Americas.” Comparative Political Studies, 39(4): 415-440. Andreassi, Celina. 2011. “The History of the UCR (part II).” Argentina Independent, posted September 26th. www.argentinaindependent.com/currentaffairs/analysis. Baumgartner, Jody C., and Naoko Kada. (Eds.). 2003. Checking Executive Power: Presidential Impeachment in Comparative Perspective. Westport, CT: Praeger. Cheibub, Jose A. 2002. “Minority Governments, Deadlock Situations, and the Survival of Presidential Democracies.” Comparative Political Studies, 35: 284-312. Cheresky, Isidoro 1990. “Argentina. Un paso en la consolidación Democrática: Elecciones Presidenciales con Alternancia Política.” Revista Mexicana de Sociologia, 52(4): 49-68. Corrales, Javier. 2002. “The Politics of Argentina's Meltdown.” World Policy Journal, 19(3): 29- 42. Deheza, Grace I. 1998. “Gobiernos de Coalición en el Sistema Presidencial: América del Sur.” In El Presidencialismo Renovado: Institucionalismo y Cambio Político en América Latina, eds. Dieter Nohlen and Mario Fernández. Caracas, Venezuela: Nueva Sociedad. Ferreira Rubio, Delia, and Mateo Goretti. 1998. “When the President Governs Alone: The Decretazo in Argentina, 1989-93.” In Executive Decree Authority, Eds. Carey, John M. and Matthew S. Shugart. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 31 Hochstetler, K. 2006. “Rethinking Presidentialism: Challenges and Presidential Falls in South America.” Comparative Politics, 38(4): 401-418. Hochstetler, Kathryn, and Margaret E Edwards. 2009. “Failed Presidencies: Identifying and Explaining a South American anomaly.” Journal of Politics in Latin America, 1(2): 31- 57. Kim, Young Hun, and Donna Bahry. 2008. “Interrupted Presidencies in Third Wave Democracies.” The Journal of Politics, 70(3): 807-822. Krauss, Clifford. 2001. “Reeling from Riots, Argentina Declares a State of Siege.” New York Times, posted December 20th. www.nytimes.com/2001/12/20/international/20ARGE.html Levistky, Steven, and Maria V. Murillo. 2003. “Argentina Weathers the Storm.” Journal of Democracy, 14(4): 152-166. Lijphart, Arend. 1999. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty- six Countries. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Linz, Juan J. 1990. “The Perils of Presidentialism.” Journal of Democracy, 1(1): 51-69. Linz, Juan J. 1994. “Presidential or Parliamentary Democracy: Does it Make a Difference?” In The Failure of Presidential Democracy, eds. Linz, Juan J. and Arturo Valenzuela. Baltimore, MA: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Llanos, Maria. and Ana Margheritis. 2006. “Why do Presidents Fail? Political Leadership and the Argentine Crisis (1999-2001).” Studies in Comparative International Development, 40(4): 77-103. Llanos, Maria. 2010. “Presidential Breakdowns in Argentina.” In Presidential Breakdowns in Latin America: Causes and Outcomes of 32 Executive Instability in Developing Democracies, Eds. Llanos, Maria and Leiv Marsteintredet. New York, NY: Palgrave McMillan. Llanos, Maria, and Leiv Marsteintredet, eds. 2010. Presidential Breakdowns in Latin America: Causes and Outcomes of Executive Instability in Developing Democracies. New York, NY: Palgrave McMillan. Mahoney, James, and Villegas, Celso M. 2008. Historical Enquiry and Comparative Politics. In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics, Eds. Boix, Carles and Susan C. Stokes. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press. Mainwaring, Scott, and Matthew S. Shugart. 1997. “Presidentialism and the Party System.” In Presidentialism and Democracy in Latin America, Eds. Scott Mainwaring and Matthew S. Shugart. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Ministerio del Interior de Argentina. 2008. Historia electoral Argentina (1912-2007). Buenos Aires: Presidencia de la Nacion Argentina. Montalbano, William D. 1985. “Argentine General Strike, Protests over IMF Role Challenge Alfonsín.” Los Angeles Times. Posted th May 24 . http://articles.latimes.com/1985-0524/news/mn17074_1_imf-agreement Mustapic, Ana M. 2000. “’Oficialistas y diputados’: Las Relaciones Ejecutivo-Legislativo en la Argentina.” Desarrollo Económico, 39(156): 571-595. Mustapic, Ana M. 2002. “Oscillating Relations: President and Congress in Argentina.” In Legislative Politics in Latin America, Eds. Scott Morgenstern and Benito Nacif, and Peter Lange. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 33 Mustapic, Ana M. 2010. “Presidentialism and Early Exits: The Role of Congress.” In Presidential breakdowns in Latin America: Causes and outcomes of executive instability in developing democracies, Eds. Maria Llanos and Leiv Marsteintredet. New York, NY: Palgrave McMillan. Negretto, Gabriel N. 2006. “Minority Presidents and Democratic Performance in Latin America.” Latin American Politics & Society, 48(3): 63-92. Pérez-Liñán, Anibal. 2007. Presidential Impeachment and the New Political Instability in Latin America. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Przeworski, A. and Limongi, F. 1997. “Modernization: Theories and Facts.” World Politics, 49(2): 155-183. Schamis, Hector E. 2002. “Argentina: Crisis and Democratic Consolidation.” Journal of Democracy, 13(2): 81-94. Schuster, F.L., Perez, G.J., Pereyra, S., Armesto, M., Armelino, M., Garcia, A.,…Zipcioglu, P. (2006). Transformaciones de la protesta social en Argentina, 1989-2003. Grupo de Estudios Sobre Protesta Social y Acción Colectiva. Universidad de Buenos Aires. Retrieved from <vanina-ue.academia.edu> Thibaut, Bernhard. 1998. “El Gobierno de la Democracia Presidencial: Argentina, Brasil, Chile y Uruguay en una Perspectiva Comparada.” In El Presidencialismo Renovado: Institucionalismo y Cambio Político en América Latina, Eds. Dieter Nohlen and Mario Fernández. Caracas, Venezuela: Nueva Sociedad. Valenzuela, Arturo. 2004. “Latin American Presidencies Interrupted.” Journal of Democracy, 15(9): 6-19. 34 World Bank. (2011). World dataBank.World Development Indicators and Global Development Finance. Retrieved November 29th, 2010 from databank.worldbank.org 35