VAP –Toolkit - community360.net

advertisement

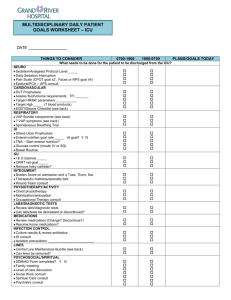

CSTSS-Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Prevention Toolkit The purpose of this toolkit is to support your efforts in implementing evidence-based practices and improve care for all cardiac surgery patients. Many of the strategies outlined in this toolkit have been adopted by academic and community hospitals of varying sizes. Many of these teams have improved adherence to evidence-based practice and observed a significant reduction in their ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) rates. Your leadership is needed to achieve these results in your perioperative areas. Most of your efforts will be spent working with staff that manages patients in CSICU (respiratory therapist, nursing staff, physical therapist, other ICU personnel, attendings and surgeon). However, some of your time will be spent working with staff that manages the surgical patient in the OR, OR (prep area) and intermediate care unit and other inpatient surgical areas. We have developed a model to support your efforts to implement evidence-based practices, reduce VAP and improve care for all cardiac surgical patients. We have applied this model to improve adherence to evidence-based practices and achieved dramatic results for patients in the OR and ICU. This model has 4 stages that answer the following questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. Engage: How will this make the world a better place? Educate: How will we do this? Execute: What do I need to do? Evaluate: How will we know we made a difference? This toolkit details what you should do in each of these stages. Several tools that may help eliminate VAP in your cardiac surgical patients are provided in the appendices below ; we need your leadership to adapt these tools based on your local culture and resources. List of Appendices Appendix A: Literature Review – Head of Bed Elevation Appendix B: Literature Review – Oral Care with Chlorhexidine Appendix C: Literature Review – Subglottic Suctioning Appendix D: Literature Review – Spontaneous Awakening and Spontaneous Breathing Trials (SAT and SBT) Appendix E: Fact Sheet – Head of Bed Elevation Appendix F: Fact Sheet – Oral Care with Chlorhexidine Appendix G: Fact Sheet – Subglottic Suctioning Appendix H: Fact Sheet – Spontaneous Awakening and Spontaneous Breathing Trials (SAT and SBT) Appendix I: Fact Sheet – Policy-based or Structural Measures Appendix J: Definitions and Techniques for Oral Care with Chlorhexidine Appendix K: Definitions and Techniques for Spontaneous Awakening and Spontaneous Breathing Trials (SAT and SBT) Appendix L: Daily Data Collection Sheet and Instructions Appendix M: PowerPoint presentation – Ventilator-associated Pneumonia Appendix N: Quiz Questions for VAP Appendix O: Michigan Keystone ICU – Oral Care Toolkit Appendix P: Michigan Keystone ICU – Clinical Practice Assessment Form CSTS-VAP –Toolkit 12.05.22 © Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins Medicine 1 Engage: How does this make the world a better place? You need to help staff understand that VAP is associated with significant preventable morbidity, mortality, and costs.1-4 All mechanically ventilated patients have an increased risk of VAP and the risk increases as the number of comorbidities, surgical procedures, use of other invasive devices, etc. increases. Patients undergoing heart surgery are at a particularly high risk due to the presence of multiple comorbidities, frequent postoperative use of multiple invasive devices (eg, intraaortic balloon counterpulsation, pulmonary artery catheter), and the common use of cardiopulmonary bypass.5 There are nearly a half million inpatient cardiovascular operations occurring annually in the US. The VAP rate in this patient group is high, with published rates between 3.2 and 8.5 per 1000 ventilator days.5-8 Tamayo et.al9. 2012 found that VAP had the highest independent mortality risk factor among all ICU patients, with an increased hazard ratio in the cardiac surgery population of almost 9%. These are just some of the reasons why efforts to improve the quality of perioperative care and decrease VAP rates are paramount. Often times our frontline staff are not aware that their patients are at risk for VAP and the risks associated with VAP. Sharing this information with frontline staff can often help to engage them in efforts to improve care. To engage your colleagues, first make the problem real by telling a story of a cardiac surgical patient who suffered needless harm from VAP and share the patient’s story openly with your colleagues and leadership. Ask them if this is the kind of care they would like for their family, if this is care they are proud of, if this is the best your hospital can do? Second, post the number of people who have developed VAP each month and the total number of VAPs for the previous year in your ICU. To keep staff engaged, post a trend line so nurses and physicians can see at a glance your VAP rate and how it changes over time. Post the number of days (weeks or months) since your last VAP. Use formal and informal opportunities to talk about your compliance with evidence-based practices and about unit VAP rates. Make a point of recognizing providers who adopt evidence-based practices. Invite your hospital infection control professional or epidemiologist to become an active part of the preoperative improvement team and draw on their expertise to help with your specific challenges. Often times expressing VAP rates in terms of potentially preventable deaths, dollars and days can be more meaningful for staff and hospital leaders. To convert VAP rates into potential deaths, dollars and days attributable to your current VAP rate, visit our ‘opportunity calculator’ at http://www.hopkins medicine.org/quality_safety_research_group/our_projects/ventilator_associated_pheumonias/estimator.html. Finally, make sure your staff recognizes that benchmarking your performance against similar hospitals and striving for the 50th percentile is unacceptable for preventable complications. Your goal should be that no patient suffers harm from a preventable complication while in our hospital. You may be able to eliminate infections and any infection should be viewed as a defect. Educate: How will we accomplish this? There is a robust amount of literature that outlines effective strategies for the prevention of VAP. In 2011, we convened a committee of 155 healthcare providers, including critical care physicians and nurses, pulmonologists, infectious disease physicians, infection preventionists and respiratory therapists. This committee was tasked to develop a new VAP prevention bundle based on current guidelines and literature. Sixty-five candidate interventions were found through an extensive literature search and were presented to this committee through an iterative evaluation process. Committee members were asked to evaluate each measure for its importance in the prevention of VAP as well as the feasibility of implementation. The strategies listed below are the results from this project. A manuscript is currently being written to describe this process and the results. This work represents the first bundle of interventions specifically designed for VAP prevention and teams in this collaborative are on the leading edge of the science for VAP prevention. CSTS-VAP –Toolkit 12.05.22 © Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins Medicine 2 The following strategies were chosen by the VAP Prevention Committee described above as the most important strategies to be used for VAP Prevention. Please refer to the appropriate literature reviews in Appendices A-D for references. Strategies to employ and evaluate on a daily basis include: 1. Maintain elevation of the head of the bed to >=30 degrees 2. Perform oral care 6 times daily. 3. Use chlorhexidine while performing oral care twice daily. 4. Use of subglottic suctioning endotracheal tubes for patients ventilated for > 72 hours 5. Use of spontaneous awakening and spontaneous breathing (SAT and SBT) protocols. Other strategies are “policy based” and include: 1. Perform hand hygiene 2. Avoid supine position 3. Use standard precautions while suctioning respiratory tract secretions 4. Use orotracheal not nasotracheal for elective intubation 5. Avoid the use of prophylactic systemic antimicrobials 6. Avoid non-essential tracheal suctioning 7. Avoid gastric over-distention 8. Use a closed ETT suctioning system 9. Change closed suctioning catheters only as needed 10. Change ventilator circuits only if circuits become damaged or soiled 11. Change HME every 5-7 days and as clinically indicated 12. Provide easy access to NIVV equipment and institute protocols to promote use 13. Periodically remove condensate from circuits, keeping the circuit drain closed during the removal, taking precautions not to allow condensate to drain toward patient 14. Use an early mobility protocol Execute: What do I need to do? There are 6 steps in the VAP Prevention toolkit: 1. Educate all staff - Use powerpoint slides, short Fact sheets and Literature reviews. 2. Standardize as much as you can in the ICU setting, for example: - Assure the easy accessibility of supplies, such as daily oral tear-off care kits with chlorhexidine - Use protocols for spontaneous awakening and spontaneous breathing trials - Use protocols for use of and accessibility of equipment, such as NIVV 3. Check ICU and hospital policies to see if they are in line with the policy-based strategies listed above and work on the development of policies that are not yet in place. 4. Improve communication among providers by discussing Daily Goals during morning rounds for each patient. Discuss spontaneous awakening and spontaneous breathing trials during the rounding process. 5. Create independent redundancy to help ensure that all patients receive the evidence-based interventions they should for the prevention of VAP. 6. Monitor compliance with evidence based guidelines and VAP rates over time. Step1. Educate staff We’ve found that many healthcare providers are not aware that the interventions outlined in this ventilatorassociated pneumonia prevention bundle toolkit can dramatically improve patient outcomes and/or they are not familiar with the evidence behind each of these measures. There are 4 guidelines for the prevention of CSTS-VAP –Toolkit 12.05.22 © Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins Medicine 3 healthcare-associated pneumonia that we have used for the development of this program from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Thoracic Society, The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America and the Guidelines Committee and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. 10-12 Each of these guidelines addresses issues specific to VAP, though some are more specifically focused on VAP than others. These are excellent resources to help you educate providers and increase awareness of the evidence-based interventions for VAP Prevention. To make it easier for you to educate staff, we have summarized the effective prevention strategies into Powerpoint slides, short Factsheets and Literature reviews. We recommend that you distribute the Fact Sheets (Appendices E-I) to all providers (anesthesia, nursing, medical/surgical staff, respiratory and physical therapists etc.). For those providers that are interested, make sure that you have the Literature Reviews (Appendices A-D) for each of the topics readily available. Hold staff in-services to review the PowerPoint presentation (Appendix K) and Fact Sheets (Appendices E-I), and allow providers to have their questions answered. Track the number of providers that have attended the in-services and received the fact sheet. Continue to provide in-services until the information has been provided to at least 90% of staff. There is a correlation between compliance with evidence-based interventions and better patient outcomes. Posting run charts of compliance with the evidence-based interventions, the number of patients that developed VAP, and the number of months without a case of VAP in your ICU areas is an effective method for demonstrating to staff that their actions make a real difference in patient outcomes. Several successful education strategies focus on changing physician behavior. These include person-toperson interventions (individualized educational information packets consisting of research literature, evidence-based reviews, hospital specific data, national guidelines – Appendices A-D), brief reminders (emails, letters, phone calls), target information period reinforced via informal educational meetings and networks, and educational outreach visits (for example, involving respiratory therapy staff). Therefore, identify an appropriate forum within your cardiovascular service to formally involve ALL staff with this initiative. In our experience, physicians respond best to other physicians so the physician champion in your hospital should probably do this if at all possible. A medical staff meeting may be an appropriate forum for dissemination of this educational information. A better forum may exist in your hospital (e.g. Grand Rounds) to review the PowerPoint presentation and distribute the Fact Sheets and Literature Reviews. Ideally, this information will be disseminated to the various types of caregivers at the same time, allowing each to know what that other has learned and to allow for open discussion about local practices, barriers and plans. Step 2: Standardizing Care The reality is that most providers want to do the right thing, but ICU care is complex and it is often difficult to remember everything we should do in real-time. Strategies and policies that help to decrease complexity, like checklists, are used extensively in other industries and are increasingly being employed in health care. Standardizing care can also improve compliance with evidence-based practice. In this project, we are asking you to collect data on the following process measures daily. This will give you an accurate view of how well staff are incorporating the new processes into their daily practice. Compliance rates can be fed back to staff on a monthly basis for reinforcement. Strategies to Evaluate Daily 1. Maintain elevation of the head of the bed to >=30 degrees Several successful strategies have been published in the peer-reviewed literature to improve compliance with the measure of keeping the head of the bed at an elevation of >=30 degrees. These include the use of a bed with a specific attachment that will show the angle at a glance, the use of a handheld protractor, a determination of what mark on which bed can signify the correct angle for recline (and staff education to this effect), and the use of daily audits to assure compliance. Rates of compliance would be fed back to the unit on a regular basis. Another strategy to improve CSTS-VAP –Toolkit 12.05.22 © Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins Medicine 4 adherence to the angle of the head of the bed is to involve other professionals, like respiratory or physical therapy staff, to ensure the head of the bed is maintained at the correct angle. 2. Perform oral care 6 times daily. Compliance with recommended oral care practices can be difficult. The use of a set of “tear-off” daily oral care packets that can be hung on the wall by the patient’s bed can remind providers. This also serves as a way to track compliance. If only 4 packets have been used out of 6, 2 have not been used during that 24 hour period. 3. Use chlorhexidine while performing oral care twice daily As above, compliance can be difficult. Many of the tear-off sets mentioned above have the chlorhexidine incorporated into two of the packets. Again, remaining packets can be used both for reminders that the product needs to be used and for compliance checks. 4. Use of subglottic suctioning endotracheal tubes for patients ventilated for > 72 hours Maintaining a well-stocked supply of subglottic suctioning endotracheal tubes enables providers to choose them when clinically appropriate. At our organization we have replaced standard ETTs in code carts and emergency intubation roles with subglottic suctioning endotracheal tubes. In the OR however, the determination of which patients are most likely to be mechanically ventilated for more than 72 hours is difficult. Our goal is to learn together how we may best be able to incorporate this evidence into practice while balancing the additional costs of the special ETTs. Nevertheless, the use of these special ETTs has been shown to be exceedingly effective for VAP prevention and economic modeling suggests the use of these tubes may actually reduce cost. 5. Use of a spontaneous awakening and readiness to wean protocol. The adoption of spontaneous awakening (SAT) and spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) protocols is paramount to reducing the length of time a patient remains on mechanical ventilation. This concomitantly reduces the risk of VAP. Girard et. al.13 showed that pairing an SAT with an SBT has been shown to be effective, reducing the length of intubation by 3.1 days. Step 3: Other “policy based” strategies The implementation of hospital or unit-based protocols has also been shown to improve success with evidence-based interventions. For instance, most hospitals have existing policies and campaigns to increase hand hygiene rates. Protocol and policies in the ICU can help improve compliance. We encourage you to review your existing policies and implement additional new policies as needed to target VAP prevention that are specific to the ICU. For instance, focusing on the decision to intubate and on intubation techniques and choices, consider implementing the following policies: 1. A policy to assure the availability of NIVV equipment and standardize equipment practices - This policy defines when, where and under what conditions NIVV equipment should be used. It states that the equipment should be easily accessible to the providers working in the ICU and that it should be kept in good working condition, with the required supplies. Such a protocol without the ease of access to the equipment is not practical, and the availability of the equipment without the protocol to encourage the use will not decrease the use of mechanical ventilation on the unit. 2. To help prevent colonization of the aerodigestive tract the following policies should be used: a. A policy to encourage the use of orotracheal intubation over nasotracheal whenever orotracheal intubation is not contraindicated. b. A policy to encourage the use of closed ETT suctioning systems, and remove open systems from supplies. c. A policy to discourage the scheduled changing of closed suctioning catheters. These should only be changed as needed. d. A policy to avoid the use of prophylactic systemic antimicrobials. The use of prophylactic antimicrobials for VAP is inappropriate and long-term use of antimicrobials is known to lead to antimicrobial resistance. There are situations where prophylaxis is warranted, but these CSTS-VAP –Toolkit 12.05.22 © Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins Medicine 5 are cases where there is the possibility of a contaminated wound (trauma, surgery, etc.) or prophylaxis due to another comorbidity such as an immunodeficiency and have nothing to do with VAP. 3. To help prevent aspiration: a. A policy to keep patients in a semi-recumbent position (>=30 degrees) whenever possible, unless it is contraindicated. b. A policy to discourage the use of non-essential tracheal suctioning. Place reminders to discourage orders for regular suctioning, i.e. q. 2 hours. c. Policies to prevent gastric-over-distention. Keep feedings to a minimum volume and decompress the abdomen. For example, assuring the patient has an OGT or NGT in place if there is an anticipation of longer-term intubation. d. A policy to encourage the use of an early mobility protocol. Encouraging mobility may decrease the propensity to atelectasis and increase clearance of bronchopulmonary secretions. Several of these policy-related strategies are focused on practices for both nursing staff and respiratory therapists. 1. A policy that promotes the use of standard precautions while suctioning respiratory secretions. This is very important for both the protection of the healthcare provider and for their patients. If the patient does have an infection or is colonized with a communicable organism, standard precautions can protect the healthcare provider and their subsequent patients. 2. Closed suctioning catheters should only be changed as needed. This can help prevent the patient from colonization of the lower respiratory tract which might lead to infection. Change only when needed to minimize this risk. 3. In order to protect the patient from inadvertent contamination, the ventilator circuit should be periodically drained and during this procedure the caregiver should take care not to allow the condensate to drain toward the patient. 4. The ventilator circuits should only be changed if damaged or soiled. 5. Heat moist exchangers (HMEs) should be changed every 5-7 days and as clinically indicated. Implementation of these protocols and interventions may look overwhelming, but if you approach it with the goal of VAP reduction and take the policy changes in groups, i.e. all equipment related changes. The process will be easier. Far too many patients suffer preventable harm. Our goal is to eliminate that harm. Step 4: Improve communication among providers One powerful strategy to improve communication and to increase the likelihood that patients will receive the therapies they should is the ‘Daily Goals’ form. The Daily Goals form is filled out every day on every patient and has been successfully used in the ICU. We will be talking much more about the Daily Goals form during this project. We encourage you to explore the use of the Daily Goals form as part of this project and specifically as we work together to prevent VAP. Step 5: Create independent redundancy Creating independent redundancy involves developing unique and separate system checks for critical procedures. High reliability industries use independent redundancies to monitor those procedures that are highest risk or most likely to cause harm if not done correctly. We are just beginning to develop independent redundancies in healthcare. We see many opportunities to create redundancy and to improve adherence with the VAP prevention measures. For example, you can adopt the use of a tear-off oral care tool as mentioned above, and you can post standardized laminated posters in every ICU room delineating the criteria and steps for the spontaneous awakening and spontaneous breathing trials. In addition, all appropriate healthcare providers can be given laminated pocket guides to have with them at all times. CSTS-VAP –Toolkit 12.05.22 © Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins Medicine 6 Another successful idea is to incorporate redundancy at the time of nurse-to- nurse or RT-to-RT handoffs. For example, these handoffs typically include important information about the patients on the ventilator, such as oxygenation status, status history, particulars about attempted SATs and SBTs, etc. To create redundancy, these handoffs could include a checklist to assure that patients are receiving their needed therapies. There are several other ways to create redundancy in the system. Consider incorporating SAT and SBT reminders using computer decision support systems. Computerized decision support is one of the most effective tools described in the literature. Automated reminders, supported by computer-based decision systems, lead to reductions in human error (error of omission) and decrease the variability of the process. Engaging all caregivers can provide another independent redundancy. Include respiratory and physical therapists, nurses and pharmacists in the care choices that are made. Talk to your front line providers! They likely have many many other suggestions for creating redundancy in your system. Summary: Suggestions for creating redundancy Oral care tear off packets Posters for reinforcement of SAT and SBT steps Adding reminders and standing orders to computer decision support systems. Require answers! Include all healthcare provider types in the decision making process. Use a protocol for RN to RN and RT to RT handoffs. Set up a checklist that meets the needs of your site. Talk to your front line providers for other suggestions for creating redundancy in your system. We suspect you will be able to identify additional opportunities to create redundancy in your ICU and we hope that you will share your ideas with other ICUs. Nevertheless, there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution that will be effective for every health care setting. Implementation of the different strategies and suggestions must be adapted based on the situations and circumstances of every clinical setting. Step 6: Monitor compliance with evidence based guidelines Conducting periodic audits with continuous timely feedback of both process and outcome measures to all staff involved in this quality improvement process is essential. To accomplish this, we recommend that you monitor compliance with the evidence-based process measures above and report back to your staff each month. Share the reports for percentages of compliance for each measure with your team to help them track their performance. Also let your staff know about each month that goes by without a VAP!! Evaluate: How will we know that we added value? The first step is to collect 2 years of baseline VAP rates in your unit. Enter this information into the electronic database. As your monthly VAP rates improve, you will need to have these rates for comparison. When you begin the project, enter your VAP rates monthly. Comparing monthly rates against the baseline and other ICUs will give you the incentive you need to keep focus on your work towards eliminating VAP in your unit. The more real-time data you have access to the better. We partnered with Quality Improvement Department to send letters from the ICU leadership to providers who were not compliant with a given measure and requested that they investigate why the defect occurred and submit a response for the team to review. This enhances the sense that everybody is responsible for the successes – and the failures. Furthermore, while the Quality Improvement Department had previously been investigating each defect, the front line providers frequently had important insights into why there was a failure and new protocols, guidelines or practices have been implemented as a result. CSTS-VAP –Toolkit 12.05.22 © Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins Medicine 7 REFERENCES 1. Safdar N, Dezfulian C, Collard HR, Saint S. Clinical and economic consequences of ventilator-associated pneumonia: A systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(10):2184-2193. 2. Edwards JR, Peterson KD, Mu Y, et al. National healthcare safety network (NHSN) report: Data summary for 2006 through 2008, issued december 2009. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37(10):783-805. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.10.001. 3. Chastre J, Fagon JY. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(7):867-903. 4. Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL,Jr, et al. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(2):160-166. 5. Leal-Noval SR, Marquez-Vacaro JA, Garcia-Curiel A, et al. Nosocomial pneumonia in patients undergoing heart surgery. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(4):935-940. 6. Bouza E, Pérez M, Muñoz P, Rincón C, Barrio J, Hortal J. Continuous aspiration of subglottic secretions in the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in the postoperative period of major heart surgery.. Chest. 2008;134(5):938-46. 7. Rebollo MH, Bernal JM, Llorca J, Rabasa JM, Revuelta JM. Nosocomial infections in patients having cardiovascular operations: A multivariate analysis of risk factors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112(4):908-913. 8. El Solh AA, Bhora M, Pineda L, Dhillon R. Nosocomial pneumonia in elderly patients following cardiac surgery. Respir Med. 2006;100(4):729-736. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.07.011. 9. Tamayo E, Alvarez FJ, Martinez-Rafael B, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia is an important risk factor for mortality after major cardiac surgery. J Crit Care. 2012;27(1):18-25. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.03.008. 10. Tablan OC, Anderson LJ, Besser R, Bridges C, Hajjeh R. Guidleines for preventing healthcareassociated pneumonia, 2003: Recommendations of CDC and the healthcare infection control practices advisory committee. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53:1-36. 11. American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388-416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. 12. Coffin S, MD, Klompas M, MD, Classen D, MD, et al. Strategies to prevent Ventilator‐Associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals • . Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2008;29(S1, A Compendium of Strategies to Prevent Healthcare‐Associated Infections in Acute Care Hospitals):pp. S31S40. 13. Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, et al. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (awakening and breathing controlled trial): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9607):126-134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60105-1. CSTS-VAP –Toolkit 12.05.22 © Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Johns Hopkins Medicine 8