Government Intervention

advertisement

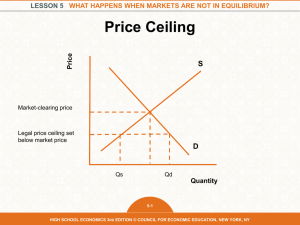

Government Intervention We have studied the way markets work under normal conditions. There are times where government may intervene in the free market which changes the market equilibrium and cause market disequilibrium. In this chapter we will discuss two types of such conditions which are price ceilings and price floors. Let us begin with price ceilings. Price Ceiling or maximum price: A price ceiling occurs when the price is artificially held below the equilibrium price and is not allowed to rise. Thus maximum price < Pe ; For example, in many cities, there are rent controls. This means that the maximum rent that can be charged is set by a governmental agency. This rent is usually allowed to rise a certain percent each year to keep up with inflation. However, the rent is below the equilibrium rent. Also, from 1973 to 1981, there was a price ceiling for gasoline. There was a maximum price allowed by law. Any gas station owner charging more than this maximum price would be guilty of fraud. During World War II, there were price ceilings on most products. Maximum price: price ceiling P S Pe maximum price shortage D O Qs Qd Q This type of price control leads to shortages because the control price is below the market price where demand will be more than supply. Total shortages = QCD – QCS. Government may set a maximum price for reasons of fairness. In wartime, or times of famine, the government may set maximum prices for basic goods so that poor people can afford to buy them. The resulting shortages, however, create further problems. If the government merely sets prices and does not intervene further, the shortages will lead to the following: Allocation on a ‘first come, first served’ basis. This is likely to lead to queues developing, or firms adopting waiting lists. Queues were a common feature of life in the former communist east European countries where governments kept prices below the level necessary to equate demand and supply. In the 1990s, as part of their economic reforms, they lifted price controls; this had the obvious benefit of reducing or eliminating queues. However, the consequential sharp increase in food prices made life very hard for those on low incomes. Firms deciding which customers should be allowed to buy: for example, giving preference to regular customers. Government may adopt a system of rationing. People could be issued with a set number of coupons for each item rationed. Further effects of Price Ceilings It creates black markets, where customers, unable to buy enough in legal markets, may well be prepared to pay very high prices: prices above the price ceiling. So, for example, tickets to popular events are sold by scalpers at high prices. A gray market is a way of getting around the price ceiling without actually doing anything illegal. There are two forms of gray market. One form of gray market involves charging for goods or services that were formerly provided free. If the rent cannot be raised on the apartment, there is nothing preventing the landlord from charging for the parking space, charging for use of the elevator, charging for gardening and cleaning services, forcing the tenants to pay for electricity and water, and so forth. In New York, a rent-controlled apartment near Central Park might rent for $300 to $400 per month; in a free market, the rent would probably be $2,000 per month. To get in, one needs the key. This has been known to cost $1,000. This is not a refundable deposit; this is a charge to have the key. It is obviously worth it to be able to rent the apartment for $300 to $400 per month. A Berkeley apartment owner converted his apartment into a church. To be able to live there, one had to pay church dues of $1,200 per year in addition to the rent. Gasoline stations would commonly charge for washing the windows, checking the tires, and so forth. The price of oil used in oil changes would be raised. (Those having oil changes at the station were favored in access to gasoline during the years of the price ceiling. In these years, Americans had the cleanest engines in history.) Some gas station owners ran the line to the gasoline pump through the car wash. One San Diego station forced people to have a $7 car wash to get to the gasoline pump. ($7 in these years is the equivalent of about $20 today.). This practice was later declared illegal. The second form of gray market is to provide less service for the same price. The apartment owner would not repair, clean, paint, nor otherwise maintain the apartment building. Some people argue that rent controls are one reason for the dilapidated state of many apartments in New York and for the fact that nearly half of furnaces in New York apartment buildings do not work. The gasoline companies would lower the octane rating. Unleaded gasoline, which was 91 octane, becomes 89 octane and then 87 octane. (For a while, Texaco even tried 85 octane.) If you want 91 octane, you must now buy Super Unleaded, and pay $0.30 per gallon extra. Price Floor or Minimum price The government sets the price floor above the equilibrium price and stops the price from falling to a certain level. Minimum price > Pe. A minimum price creates a surplus, since Supply will be more Demand (QS>QD). Minimum price: price floor P S surplus minimum price Pe D O Qd Government may do this for many reasons: Qs Q To protect producers’ incomes. If the industry is subject to supply fluctuations (e.g. fluctuations in weather affecting crops), prices are likely to fluctuate severely. Minimum prices will prevent the fall in producers’ incomes that would accompany periods of low prices. To create a surplus (e.g. of grains) – particularly in periods of glut – which can be stored in preparation for possible future shortages. In the case of wages (the price of labour), minimum wage legislation can be used to prevent workers’ wage rates from falling below a certain level The government can use various methods to deal with the surpluses associated with minimum prices. The government could buy the surplus and store it, destroy it or sell it abroad in other markets. Supply could be artificially lowered by restricting producers to particular quotas. Demand could be raised by advertising, by finding alternative uses for the good, or by reducing consumption of substitute goods (e.g. by imposing taxes or quotas on substitutes, such as imports).