Chapter 32 Summary Few presidential election years have begun

advertisement

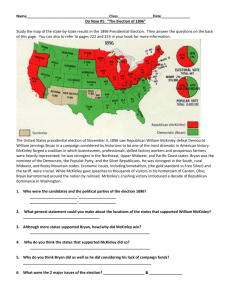

Chapter 32 Summary Few presidential election years have begun as anxiously as 1896 did. Republicans nominated William McKinley and endorsed a gold standard platform. The Democrats chose a free-silver advocate named William Jennings Bryan. The Populist Party followed suit and nominated Bryan as well. Before 1896, few presidential candidates actively campaigned. Not Bryan. He ran. Republican speakers and editors contrasted McKinley’s self-respect with Bryan’s vulgar huckstering. McKinley won decisively in the electoral college. The twenty-year equilibrium of the two major political parties was over and done with. Populistic sentiments remained high in the South but not the Populist Party. In 1890, 90 percent of the African American population lived in the southern states. Redeemers had long since neutralized blacks as a political power to be reckoned with. Between 1889 and the early 1900s, every southern state adopted one or another device to ensure that few blacks voted. The final years of the 1890s and the early 1900s were an era of lynchings in the South. In 1881, Booker T. Washington was hired as the first president of Tuskegee Normal School for Negroes in Alabama. He proposed the Atlanta Compromise in 1895: In return for black acquiescence in Jim Crow and disenfranchisement, he asked southern state governments and wealthy whites to fund mechanical, technical, and agricultural education for African Americans. In 1896, Plessy v. Ferguson legitimized the doctrine of "separate but equal." William McKinley hoped for a quiet presidency. McKinley got prosperity, peace, and quiet were more elusive. By 1890, the United States was the world's leader in industrial power and agricultural production. The United States was not, however, even a third-rate military power. The anti-colonial tradition was alive and apparently well in 1897. The "frontier thesis," however, implied that the United States might stagnate unless economic, social, and moral decline was averted by creating new frontiers in colonies overseas. Some posited that the Americans had a racial and religious duty to colonize. When a Cuban rebellion broke out against the Spanish, American public opinion favored the rebels. Sensing a hot issue that would sell newspapers, the heads of two fiercely competitive newspaper syndicates, William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, adopted the rebels. McKinley wanted no part of the rebellion. The de Lome letter and the explosion of the Maine forced McKinley into action. On April 11, 1898, the president asked Congress for a declaration of war and he got it. The tiny U.S. Army was not up to launching a plausible overseas operation, but the spanking new navy was. A few days after the victory at San Juan Hill, Congress annexed the Republic of Hawai’i. With victory against the Spanish, questions arose over what to do with the newly acquired lands. Annexationists declared that Americans had a religious and racial duty to govern peoples who were incapable of governing themselves. Unlike the war with Spain, the pacification of the Philippines was neither easy, cheap, nor glorious. McKinley won reelection in 1900 with a new vice president, Theodore Roosevelt. However, McKinley was assassinated within a year.