Politics in Japan

advertisement

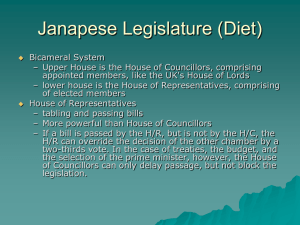

1 of 63 Country Bio: Japan • Population: – 127.1 million – Jiangsu and Zhejiang Provinces combined • Territory: – 145,882 square miles – Smaller than Yunnan Province • Year of Independence: – 660 B.C. 2 of 63 Country Bio: Japan • Year of Current Constitution: – 1947 • Head of State: – Emperor Akihito • Head of Government: – Prime Minister Naoto Kan 3 of 63 The Tokugawa Clan 1600-1868 • In 1600, the Tokugawa clan finally managed to achieve preeminence and a considerable degree of national unity. • The Tokugawa family ruled from Edo, present-day Tokyo, from 1600 to 1868. • After over 250 years of virtual isolation, a U.S. naval officer, Commodore Matthew C. Perry, sailed a small fleet into what is now known as Tokyo Bay in 1853. 4 of 63 The Meiji Restoration 1868 • This action emboldened regional barons to depose the Tokugawa clan and “restore” the emperor to power. • The Meiji Restoration (1868), as this transition is called, was named for the young Emperor Meiji, who was nominally installed as the supreme political and religious leader. 5 of 63 The Meiji Restoration 1868 • Although the new oligarchs had no intention of democratizing politics on any mass level, they did relent to the establishment of a constitution with an elected legislature. • The government established the Diet, a bicameral legislative body, on the model of European parliamentary democracy. 6 of 63 The 1889 Constitution • The 1889 constitution had given the Diet the ability to reject certain governmental actions (specifically the budget), so that the cabinet had to bargain with nascent political parties on many issues. • This creeping democratization reached its prewar apex from 1918 to 1932. 7 of 63 The Occupation • It was not until Japan’s surrender in August 1945, and its subsequent occupation by the Allied powers, that the military’s role in politics was ended and civilian democracy was allowed to flourish. • The Allied Occupation of Japan was administered by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), under the direction of U.S. General Douglas MacArthur. 8 of 63 The Occupation • Its initial objectives were to demilitarize and democratize Japan, to render Japan unable and unwilling to wage war ever again. • This idealism was discarded rather quickly in the face of Communist advances in China and increasing conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union. 9 of 63 The 1947 Constitution • Perhaps the best known provision of the Japanese Constitution is Article 9, the “Peace Clause,” in which Japan renounces the right to wage war or even to maintain a military capability. • Conservative governments and courts have interpreted the provision flexibly (to say the least) to allow for a defensive capability. 10 of 63 The 1951 Peace Treaty • The priorities of SCAP shifted from the demilitarization of Japan to securing Japan as a reliable ally in the Cold War. • In September 1951, Japan signed a general peace treaty in San Francisco with all Allied powers except the Soviet Union (and China), formally ending the Occupation and ceding Japan’s postwar autonomy. 11 of 63 The US-Japan Security Treaty • At the same time, the U.S.-Japan Mutual Security Treaty was signed. • This treaty allowed the United States to station troops in Japan and to continue to occupy Okinawa as a military base, a vital link in the U.S. anticommunist “containment strategy” during the Cold War. 12 of 63 Watershed Events since WWII • Postwar Japanese politics is chock-full of fascinating personalities and episodes, but four watershed events stand out. • The first was the promulgation of the postwar Constitution in 1947, which established Japan’s political institutions and specified their relative shares of political power. 13 of 63 Watershed Events since WWII • The second was the 1955 party merger that resulted in the formation of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which was to govern Japan for the next four decades. 14 of 63 15 of 63 Watershed Events since WWII • The third was the 1960 U.S.-Japan Mutual Security Treaty crisis, which both crystallized the foreign policy cleavage that persisted until the end of the Cold War and induced the government to downplay such issues and instead place economic growth squarely on the front burner. 16 of 63 Watershed Events since WWII • The fourth was the temporary fall of the LDP from power in 1993, and the subsequent adoption of new electoral rules in 1994. 17 of 63 The National Diet • Japan’s system of government is parliamentary, bicameral, and, despite the existence of elected local governments, nonfederal. • Article 41 of the Constitution specifies that the parliament, the National Diet, “shall be the highest organ of state power, and shall be the sole law-making organ of the State.” 18 of 63 The National Diet • Thus, there is no separately elected executive with whom the Diet must share policymaking authority. • The Diet consists of two legislative chambers: – the House of Representatives (the Lower House) – and the House of Councillors (the Upper House). 19 of 63 The National Diet • Both chambers must pass a bill in identical form for it to become law, with three important exceptions: • the House of Representatives alone – chooses the prime minister, – passes the budget, – and ratifies treaties. 20 of 63 The House of Representatives • As in all parliamentary systems, the first business that any new parliament must conduct (after an election) is to elect one of its members to serve as prime minister. • The person elected is usually, but not always, the leader of the largest party in the Lower House. – During the LDP’s long reign as majority party, the LDP leader always won that prize. 21 of 63 The House of Representatives • The new prime minister then appoints a cabinet, at least half of whose members must be legislators. • These appointees head up the cabinetlevel ministries and agencies that comprise the central government bureaucracy. 22 of 63 23 of 63 Local Government • Japan is divided administratively into fortyseven prefectures, each of which elects its own governor and legislature. – The country’s hundreds of municipalities elect their own mayors and city councils as well. • Nevertheless, Japan is not a federal system: all local government authority is delegated, and may be retracted, by the national government. 24 of 63 The Judiciary • The Japanese legal system ostensibly features the same degree of judicial independence that courts in the US enjoy. • Such independence is guaranteed in the Constitution. • Nonetheless, independence does not appear to be the reality in Japan. 25 of 63 The Judiciary • Political domination and manipulation of the courts have arisen from a combination of the LDP’s long reign and its ability to use appointment powers and bureaucratic mechanisms to avoid putting courts into positions where they might render decisions anathema to LDP interests. 26 of 63 The Judiciary • In a unitary parliamentary system, especially one with a long-tenured majority party, there are fewer checks and balances, and hence fewer conflicts for courts to mediate, other things equal. • It will be interesting to see if this practice changes now that LDP control of government is over. 27 of 63 The Judiciary • The Cabinet directly appoints the fifteen members of the Supreme Court, and indirectly, through the administrative apparatus of the Supreme Court, helps to determine all lower court appointments as well. • The Supreme Court, through its Secretariat, controls the career paths of lower court judges. 28 of 63 Electoral Systems • The two chambers of the National Diet use different electoral rules. • The rules for the more powerful House of Representatives were changed in 1994. • According to the Constitution, members of the House of Representatives are elected to four-year terms, but these terms usually end early, as the prime minister may dissolve the chamber and call elections at any time. 29 of 63 New Electoral Rules • In January 1994, several months after wresting power from the LDP, a sevenparty coalition government enacted a major restructuring of the Lower House electoral rules. • The new rules set the size of the House of Representatives at 500 seats, later reduced to 480. 30 of 63 New Electoral Rules • Of these, 300 are elected on the basis of equal-sized single-member districts, and 180 (originally 200) are elected from eleven regional districts by proportional representation (PR). • Each voter casts two votes: one for a candidate in the single-member district, and one for a party in the PR region. 31 of 63 New Electoral Rules 32 of 63 Political Participation • By international standards, the political involvement of ordinary Japanese is low. • Voters generally identify with political parties based on personal identification with a candidate or association with a party-affiliated interest group. 33 of 63 Voter Turnout in Elections • Voter turnout at election time has been declining steadily on a nationwide basis. • Recently, party identification has declined as well, as self-proclaimed “independents” now make up the largest group of respondents in public opinion polls. 34 of 63 Voter Turnout in Elections • It is unclear whether it represents a worrisome new political alienation or whether it is simply a sign that Japanese democracy has matured, • now that Japanese voters seem as apathetic and complacent about politics as their counterparts in other advanced democracies. 35 of 63 Political Culture • In discussions of Japanese political culture, the concepts of hierarchy, homogeneity, and conformity to group objectives take center stage. • Social hierarchy governs most Japanese relationships. • In the family, in the workplace, and in politics, the hierarchical traits of loyalty and obligation can be found. 36 of 63 Political Culture • Japanese political behavior and economic success have also been attributed, at least in part, to ethnic and cultural homogeneity. • This homogeneity has been credited with allowing Japan to focus in a unified manner on national goals, the foremost being economic growth. 37 of 63 Political Culture • An understanding of why the Japanese feel confident that they are homogeneous may be found in the lack of strong issue cleavages. • Indeed, one reason the LDP was so successful for so long at implementing a campaign strategy that downplayed issues in favor of the distribution of private goods was the simple absence of many common issue cleavages. 38 of 63 Political Culture • Studies of Japanese culture also stress the Japanese emphasis on conformity, the belief that individual goals should be sublimated to the objectives of the group. • But by itself, reference to culture can not explain many things that are interesting about Japanese politics. 39 of 63 The Policymaking Process • Japan is a parliamentary democracy, with both houses of the National Diet directly elected, and with the prime minister and the cabinet chosen by, and accountable to, the Lower House. • In practice, the Diet, like all parliaments, tends to leave the proposal of legislation to the Cabinet, reserving the right to pass, reject, or amend those proposals as it sees fit. 40 of 63 The Policymaking Process • The Cabinet, in turn, delegates the task of drafting legislation - everything from regulation to the budget - to policy experts in the bureaucracy. • The Cabinet ministers oversee this process in the broadest sense, but most of the expertise resides, and most of the action takes place, in the various bureaus and departments of the government ministries and agencies. 41 of 63 How a Bill Becomes a Law • Members of either house of the Diet may submit legislation, and they do so quite often. • But these “member bills” are almost always exercises in grandstanding for the sponsors’ constituencies, where the proposal itself is the point, and they rarely have any hope of passing into law. 42 of 63 How a Bill Becomes a Law • The typical path for new legislation proceeds as follows. • A ministry drafts legislation for some policy change in its jurisdiction and submits the bill to the Cabinet. • The Cabinet may send the bill back, reject it, or amend it in any way it wishes, but if and when it is satisfied, it submits the bill to the Diet. 43 of 63 How a Bill Becomes a Law • The Diet may then do whatever it wants with the bill. • Normal legislation must be passed in identical form by both houses, unless the Lower House can muster a two-thirds majority to override Upper House objections. 44 of 63 How a Bill Becomes a Law • Again, if the bill is the annual budget, or a treaty to be ratified, then only the Lower House need pass it; • the Upper House may delay that passage for up to thirty days, but it may not stop it. • Any bill passed by the Diet becomes the law of the land. 45 of 63 How a Bill Becomes a Law • There is no separately elected president who may veto Diet actions, and Diet laws supersede any local laws that might conflict. • The Supreme Court may declare a law unconstitutional, but this is exceedingly rare. 46 of 63 How a Bill Becomes a Law • The final steps in the process involve implementation. • The Diet can pass legislation, but it delegates to the bureaucracy the job of implementing and enforcing the new rules. • Indeed, laws are often so vague that the bureaucrats must do considerably more than robotically carry out the Diet’s orders. 47 of 63 Industrial Policy and the Miracle • Perhaps the most well-known aspect of postwar Japanese history has been the country’s remarkable economic development. • As the first industrial democracy in East Asia, Japan has been looked to as a model for other industrializing countries in the region. 48 of 63 Industrial Policy and the Miracle • Arguments over who should receive credit for Japan’s economic growth have raged for years, with three major theories contending. • The role of government intervention in the economy is at the center of each of these explanations. 49 of 63 Industrial Policy and the Miracle • The first theory stresses the role that market fundamentals have played in directing Japanese economic growth. • Japan’s high postwar growth is simply a result of returning to the growth path established before World War II. • This theory discounts any positive role for interventionist government policy in explaining Japan’s economic miracle. 50 of 63 Industrial Policy and the Miracle • A second theory, widely subscribed to both inside and outside Japan, contends that Japan’s government (or more precisely its well-trained bureaucrats) is the source of economic success. • In this account, skillful use of government in providing firms with access to capital was crucial to Japan’s economic rebirth. 51 of 63 Industrial Policy and the Miracle • Further, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI - since renamed), the bureaucratic agency in charge of industrial policy decision making, used its administrative authority to point firms in fruitful directions. 52 of 63 Industrial Policy and the Miracle • Government is also credited with retreating intelligently and carefully from declining economic sectors, such as coal, that were unlikely to prove beneficial in the future. • This view argues that MITI was adept at picking industries that would become profitable, and discarded losing economic sectors to enhance the economy as a whole. 53 of 63 Industrial Policy and the Miracle • A third view suggests that Japan has maintained a form of “strategic capitalism” requiring cooperation between the firms in an economic sector and the government over the type and depth of government involvement. • Government is most involved in economic decision making when firms can agree to limit competition among themselves. 54 of 63 Industrial Policy and the Miracle • Since the beginning of the 1990s, Japan has reeled from one recession to the next, from bad economic straits to worse. • Deflation, unemployment, and bankruptcies, all unheard of for decades, have stagnated the economy and shocked the national psyche. • Fiscal deficits are worse than ever. 55 of 63 Security and Foreign Policy • Japan’s postwar security and foreign policy have focused on maintaining a close relationship with the United States. • Bargaining from a position of weakness, Japan has been on the receiving end of most U.S. foreign policy decisions. • With the end of the Cold War, Japanese voters have become more ambivalent about the alliance. 56 of 63 Security and Foreign Policy • With national security taken care of by the U.S.-Japan Mutual Security Treaty, the Japanese government was able to focus its foreign policy on economic matters. • Recently, however, Japan has been obliged to pay for a large share of the U.S. defense commitment to all of East Asia. • Japan now pays fully 50% of all costs of deploying U. S. troops on Japanese soil. 57 of 63 Welfare Policy: Health Care • Health care in Japan is universally covered through a governmentadministered, single-payer program that requires all individuals to pay a health insurance premium based on income level. 58 of 63 Welfare Policy: Health Care • Standards of service are below what is commonly found in the U.S. private system, but the coverage ensures widespread access to basic health services. • Despite many failings, the benefits of Japan’s health care system are clear. 59 of 63 Welfare Policy: Health Care • Infant mortality is the lowest among industrialized nations, and life expectancy is the highest. • The Japanese accomplish this even though public spending on health care constitutes a smaller percentage of GNP in Japan than in the US (6.6%), Britain (5.8%), France (8%), or Germany (8.2%). 60 of 63 Welfare Policy: Pensions • On pension policies, the Japanese government has been much less active. • Public and private pensions are meager. • Nonetheless, overall welfare spending has grown steadily as Japanese society has aged. 61 of 63 Welfare Policy: Pensions • An aging society in Japan will exacerbate the costs of present welfare benefits and increase the political desirability of expanding such programs. • Reductions of existing benefits may become more common as the government strives to keep up with the demographic changes that increase the number of people demanding assistance. 62 of 63 63 of 63