lec3_552_NucTraff_20..

advertisement

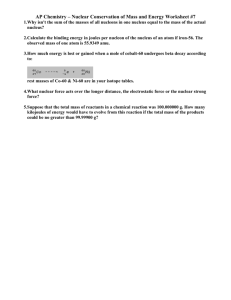

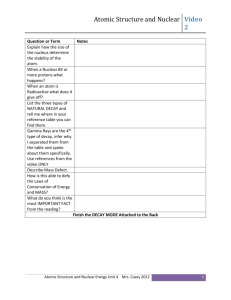

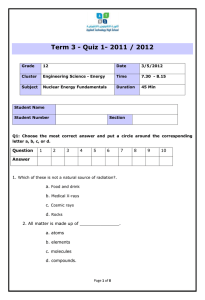

Nuclear Function and Trafficking Lecture Outline: 1. The Nucleus in Context A. Compartmentalizing DNA into the nucleus B. Origin of the nucleus C. ER is continuous with nuclear membrane 2. Organization and Function of the Nucleus A. Comparison of complexity of transcription/translation in eukaryotes & prokaryotes B. DNA synthesis C. RNA synthesis and processing D. Non-membraneous compartments in the nucleus E. Splicing F. Ribosome assembly G. Processing of eukaryotic mRNA for export 3. The Nuclear Membrane A. Function B. Structure 4. The Nuclear Pore Complex A. Structure of the NPC B. Molecular components of the NPC April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 1 Trafficking In and Out of the Nucleus Lecture Outline, cont.: 5. Trafficking through the Nuclear Pore A. Functional relevance B. Mechanism of nuclear trafficking C. Mechanism of nuclear import D. Mechanism of nuclear export E. Shuttling proteins F. Specific nuclear export proteins G. Specific nuclear export pathways 6. Experimental Approaches used to Study Nuclear Trafficking 7. Examples from Pathobiology A. Regulation of NF-kB transport B. NFAT, a shuttling protein C. How HIV-1 exploits cellular trafficking machinery for genomic RNA export D. How other retroviruses exploit cellular trafficking machinery for RNA export E. How nuclear import machinery is exploited by adenovirus for viral entry F. Herpesvirus egress 8. References April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 2 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 1. The Nucleus in Context: Prokaryotic cell A. Compartmentalization of the nucleus: A key feature of eukaryotic cells 1. Eukaryotic but not prokaryotic cells contain a nucleus that sequesters DNA 2. Other differences between eukaryotes and prokaryotes: Larger cell volumes in eukaryotes Presence of cytoskeleton in eukaryotes Elaborate set of internal membranes and organelles in eukaryotes Larger amounts of DNA in eukaryotes, and more regulatory non-coding DNA Metabolism of eukaryotes is dependent on oxidation occurring in mitochondria Eukaryotic cell 3. Note: single cell eukaryotes are called protists & include yeast and protozoa April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 3 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 1. The Nucleus in Context, cont.: B. Origin of the Nucleus: Most likely, from invagination of PM of an ancient bacterium. Note: Topology of a compartment can be determined from its evolutionary origins. Thus the interior of the nucleus is the topological equivalent of the cytoplasm. C. The ER is continuous with the nuclear membrane. ER lumen is continuous with the space between the inner and outer membrane, and topologically equivalent to the extracellular space. Evolution of the Eukaryotic Nucleus April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 4 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 2. Organization and Function of the Nucleus A. Comparison of Complexity of Transcription/Translation in Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 5 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 2. Organization and Function of the Nucleus B. DNA replication: in mammalian cells occurs in clustered sites throughout nucleus C. RNA synthesis and processing: Types of RNA: Ribosomal RNAs (rRNA )= made/processed/assembled in nucleolus; made by RNA Pol I and III; constitutes 80% of RNA in some cells; methylated using snoRNAs Small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNA)= guide RNAs used for processing rRNAs, snRNAs Messenger RNA (mRNA) = made by Pol II; are processed in nucleus (see below), then exported and undergo translation in cytoplasm Transfer RNA (tRNA) = ~80 nt; synthesized by Pol III; different ones for different aa’s, aminoacylated then export to cytoplasm; provide aa’s for translation Small nuclear RNAs (snRNA) = < 200 nt; components of the spliceosome; U1-U6 SnoRNAs are used as guides in the processing of rRNA precursors April 4, 2006 tRNA structure J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 6 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 2. Organization and Function of the Nucleus, cont. D. Non-membraneous compartments in the nucleus: Nucleolus: Site where rRNAs, tRNAs and some snRNPs are synthesized, processed, and assembled into RNPs. Also contains snoRNAs that act as guides for RNA modifications. Site of assembly of ribosomes. Cajal bodies/ GEMS: sites where snRNAs and snoRNAs undergo modification and final assembly events. Speckles or interchromatin granular clusters: storage site for mature snRNPs Compartments in the Nucleus: April 4, 2006 Bright pink = Cajal bodies Dark pink = nucleoli Green = speckles Blue = bulk chromatin J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 7 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 2. Organization and Function of the Nucleus, cont. E. Splicing: 1. UsnRNAs: Transcribed in nucleolus, exported via Crm1 pathway to cytoplasm where they associate with snRNP proteins (see below). Import back into nucleus for final modification and assembly in Cajal bodies and Gems. Storage in nuclear speckles. 2. Machinery consists of: 5 small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), U1, 2, 4, 5, 6 Each snRNA is complexed with proteins to form an snRNP 3. Critical snRNP proteins include SMN, mutations in which cause spinal muscular atrophy Gemins Sm proteins 4. snRNPs form the spliceosome core Biogenesis of UsnRNPs From Dreyfus et al., Current Opinion in Cell Bio 14: 305 (2002) April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 8 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 2. Organization and Function of the Nucleus, cont. F. Ribosome assembly: 1. Nucleolus is not surrounded by a membrane. 2. Three rRNAs (5.8S, 18S, and 28S) are transcribed as a unit and then processed within nucleolus by RNA pol I. 3. One rRNA (5S) is transcribed outside nucleolus by RNA pol III & is brought into nucleolus for assembly. 4. Ribosomal proteins translated in cytoplasm & transported to nucleolus. 5. Assembly of ribosomal proteins with rRNA occurs in nucleolus. 6. Export of fully assembled large and small ribosomal subunits to the cytoplasm April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 9 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 2. Organization and Function of the Nucleus, cont. G. Processing of Eukaryotic mRNA for Export. Only a small percentage of pre-mRNAs are exported. Events that mature mRNAs must undergo in order to be exported include: 1. Marking of exon boundaries with SR proteins 2. Proper splicing of introns 3. Addition of 5’ methyl-guanosine CAP by 3 enzymes 4. Addition of 3’ poly A tail by cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factors 5. hnRNPs that help distinguish between mature and immature mRNAs: some stay in nucleus, some exit with mRNA into cytoplasm 6. Exit via interaction with specific nuclear transport receptors (i.e. TAP) April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 10 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 3. The Nuclear Membrane A. Function of the Nuclear Membrane: • • • 1. Separation of transcription from translation allows for posttranscriptional processing. 2. Limiting access of genome by proteins allows regulation of transcription. 3. Acts as a barrier for the passage of molecules between nucleus and cytoplasm. B. Structure of the Nuclear Membrane: • • • • • • 1. TWO lipid bilayers: outer nuclear membrane (OM) and inner nuclear membrane (IM). 2. Outer nuclear membrane is connected to the ER. 3. Perinuclear space is continuous with the ER lumen. 4. Different composition of OM and IM, with OM similar to ER membrane. 5. IM and OM are joined at the nuclear pore complex. 6. Nuclear lamina underlying IM provides structure & is site of chromatin attachment. April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 11 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 4. The Nuclear Pore Complex - Except during mitosis, essentially all traffic between nucleus and cytoplasm in higher eukaryotes occurs via nuclear pore complexes. A. Structure of the Nuclear Pore Complex (NPC): 1. Definition: channels for trafficking of small polar molecules, ions, & macromolecules. 2. Size: diameter = 120 nm, 8-fold rotational symmetry; molecular mass = 125 million daltons; composed of 50 -100 different proteins called nucleoporins. April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 12 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 4. The Nuclear Pore Complex, cont. A. Structure of the Nuclear Pore Complex (NPC), cont.: 3. Number: Average cell has over 4000 NPCs. 4. Channel: Pathway for free diffusion is 9 nm x 15 nm. Can open to a diameter of more than 25 nm allowing passage of large complexes. 5. Passage across the NPC: Proteins < 40 kD pass through the NPC by diffusion, but this is often inefficient. Larger proteins and RNA pass thru NPC only selectively (Gated Transport). 6. Microscopic structure: Eight spokes around a central channel connected to a ring anchored into nuclear membrane (on cytoplasmic and nuclear sides). Filaments extend from both sides forming basket on nuclear side. NPC extensions may be initial cargo-docking sites during nucleo-cytoplasmic transport. A subset of NPC components contain phenylalanine glycine (FG) repeats that act as docking sites for transport factors. April 4, 2006 From Alberts,Molecular Biology of the Cell, Fig. 12-10 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 13 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 4. The Nuclear Pore Complex, cont. B. Molecular components of the NPC: 1. Nucleoporins (NPs): Make up the cytoplasmic filaments, nuclear basket, and line the pore Contain different types of FG (Phe/Gly) repeats Nuclear transport factors make multiple sequential contacts with distinct NPs, resulting in docking and translocation of nuclear transport complexes Exact mechanism by which NPs mediate translocation of complexes unclearbut may involve sequential association with of receptor plus cargo with FG repeats lining pore From Bayliss, R. et al. Traffic 1:448 (2000) April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 14 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 4. The Nuclear Pore Complex, cont. B. Molecular components of the NPC, cont.: 2. Soluble nuclear transport receptors in cytosol and nucleus: Nuclear transport receptors include karyopherins Bind to nucleoporins (NPs) Different factors for export and import, i.e. Exportin & Importin, see below Nuclear transport factors bind to cargo (or adaptors that bind cargo) that have localization or export signals (NLS, NES) Cargo can be protein (with NLS, NES) or RNA Nuclear transport factors bind to and are regulated by RanGTP J. Lingappa, 2003 April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 15 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 4. The Nuclear Pore Complex, cont. B. Molecular components of the NPC, cont.: 3. Ran-GTP: A small GTPase that gives directionality to nuclear transport, see below Members of the Ras oncogene family (like Rab, which regulates vesicle fusion) Binds to nuclear transport receptors 4. Lamins make up the nuclear lamina: Lamins are 80 kD proteins related to intermediate filaments of cytoskeleton Form dimers that polymerize to form filaments and a lattice Associate with the inner nuclear membrane via prenylation Give structural support to the nucleus and may be involved in recruitment of nuclear envelope components Structure of the nuclear lamina From Hutchison, Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 3: 849 (2002) April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 16 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 5. Trafficking through the Nuclear Pore: A. Functional relevance of trafficking: 1. Bring into nucleus transcription factors, proteins for ribosome and spliceosome assembly, and other proteins needed for nuclear functions. 2. Export RNAs and ribosomes out of nucleus in a regulated manner. Each is exported via a specific pathway. 3. Shuttling of cellular proteins that go back and forth between nucleus and cytoplasm (nuclear transport receptors, HnRNPs, etc.). 4. Pathogens (mainly viruses) usurp nuclear trafficking machinery: Viral genome import into and export out of the nucleus Virus entry into nucleus Virus exit from nucleus Shuttling proteins encoded by viruses 5. Pathogens can also destroy cellular nuclear trafficking machinery. April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 17 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 5. Trafficking through the Nuclear Pore, cont.: B. Mechanism of Nuclear Trafficking: 1. Ran GTPase a. Little hydrolysis or exchange activity on its own. b. Regulated by GTPase-activating protein (RanGAP) that promotes hydrolysis that is predominantly in cytoplasm and guanine exchange factor (RanGEF) that promotes GTP exchange that is predominantly in the nucleus c. So, in the cytoplasm Ran exists in inactive GDP-bound form d. In contrast, in the nucleus, Ran is largely bound to GTP e. Ran gradient is critical for most nuclear transport, except bulk mRNA transport which is mediated by factors that are not karyopherins f. Ran gradient is created by having RanGap (which promotes GTP hydrolysis) only in cytoplasm and RanGEF (which promotes loading of Ran with GTP) only in nucleus from Nalkieny and Dreyfus, Cell 99:677 (1999) April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 18 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 5. Trafficking through the Nuclear Pore, cont.: C. Mechanism of Nuclear Import: Nuclear Import a. Cargo and/or adaptors encode nuclear localization signals (NLS) b. NLS can be composed of short stretches of basic amino acids, not always contiguous (can be bipartite). Other types of NLS exist. c. NLS containing proteins (NLS proteins) bind directly or via an adaptor to nuclear import receptors (i.e. Importin) d. Cargo/adaptors bind to import receptors, some of which are karyopherins (importins), in the absence of RanGTP. Note that protein cargo is completely folded (unlike in mitochondrial import). e. Importin composed of an a subunit that binds NLS and a b subunit that binds nucleoporins in cytoplasmic filaments. f. After translocation thru NPC, import receptors release cargo upon binding to Ran-GTP in nucleus. April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 19 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 5. Trafficking through the Nuclear Pore, cont.: D. Mechanism of Nuclear Export: a. Cargo and/or adaptors encode nuclear export signals (NES) b. NLS often composed of leucine rich regions. c. NES-containing proteins bind nuclear export receptors, some but not all of which are karyopherins (i.e. exportin). d. Nuclear export factors require RanGTP to bind cargo in nucleus. e. Nuclear export factors release cargo and Ran-GTP upon translocation to cytoplasm where hydrolysis of RanGTP is induced by Ran-GAP. Nuclear Import April 4, 2006 Nuclear Export J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 20 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 5. Trafficking through the Nuclear Pore, cont.: E. 1. 2. 3. 4. Shuttling Proteins (includes HIV-1 Rev, Vpr, and many other viral proteins): Proteins contain both nuclear localization and export signals (NLS + NES). These proteins shuttle back and forth between nucleus and cytosol. Rate of export and import determines in which compartment it resides. Export/ import of shuttling proteins can be regulated, i.e. by phosphorylation-dephosphorylation of residues adjacent to NLS or NES signals resulting in blockade/exposure of signals. from Nalkieny and Dreyfus, Cell 99:677 (1999) April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 21 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 5. Trafficking through the Nuclear Pore, cont.: F. Specific Nuclear Export Proteins: 1. Crm1 (Exportin), a karyopherin, mediates export of most cellular proteins that shuttle, several U snRNAs, all rRNAs, and a subset of mRNAs. Crm1 discovered because it is required for the nuclear export of late HIV-1 mRNAs (see below), other lentiviruses, and HTLV Retroviral Rev and HTLV Rex proteins are adaptor proteins that recruit Crm1 to retroviral mRNA Crm1 pathway specifically inhibited by leptomycin B (LMB) which modifies a cysteine residue present on the Crm1 protein 2. NXF proteins (include Tap) are not karyopherins; these mediate export of most mRNAs. MPMV and other simple retroviruses use Tap/Nxt as export factors. However, unlike HIV-1 and lentiviruses that encode adaptor proteins like Rev that recruit Crm 1, simple retroviruses encode a cis-acting RNA sequence (consititutive transport element; CTE) that recruits NXF protein transport factors 3. Exp-t (Exportin t), a karyopherin, mediates export of tRNA by binding directly to tRNA unlike other karyopherins that bind RNA via adaptors; only binds mature / aminoacylated tRNAs April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 22 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 5. Trafficking through the Nuclear Pore, cont.: G. Specific Nuclear Export Pathways: from Cullen April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 23 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 6. Experimental approaches used to study nuclear trafficking: • • • • • A. Permeabilized cells/ Cell-free assay: Digitonin perforates PM (because of high cholestrol conc.) releasing cytosol Nuclear membrane, nucleus, and other organelles remain intact Allows add back of cytosolic fractions, biochemical manipulations, & antibody blockade B. Immunofluorescent Tags: Transfect cells with proteins tagged with GFP, RFP, YFP, etc. Assess nuclear vs. cytoplasmic location by IF. C. Use of chimeric proteins: Import/Export signals can be engineered into heterologous proteins (usually encoding fluorescent tags) to demonstrate effect of the signal Or, fuse an adaptor onto a cargo that doesn’t bind transport receptor D. Heterokaryon assay: For proteins that are predominantly nuclear and shuttle in and out of nucleus. Nuclei transfected/injected to express tagged protein (+ marker protein that stays in "donor" nucleus) Cells are then fused to another set of cells using PEG. Examine whether tagged protein shows up in cytoplasm alone (export), or in recipient nucleus as well (export followed by import, implying shuttling). E. Biochemical Fractionation: Ultracentrifugation to separate nuclei from cytoplasm F. Inhibitors: Leptomycin B April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 24 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 7. Examples from Pathobiology A. Regulation of NF-kB Nuclear Transport: 1. Masking NLS by binding with an inhibitory protein: e.g. transcription factor NF-kB. • I-kB is an inhibitory protein that forms an inactive complex with NFkB in cytosol. • I-kB binding masks the NLS of NFkB, preventing its translocation into the nucleus. • Upon stimulation of lymphocytes, I-kB is phosphorylated and ubiquitinated resulting in proteasome-mediated degradation of I-kB. • Once released from I-kB, NF-kB can translocate into nucleus & activate transcription. 2. Note that for other proteins, NLS can be masked by direct phosphorylation of residues adjacent to the NLS. April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 25 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 7. Examples from Pathobiology, cont.: B. Regulation of NF-AT, a shuttling protein: Phosphorylated NF-AT is found in the cytosol of resting T cells. T cell activation leads to increased intracellular Ca+2 and dephosphorylation of NF-AT (via calcineurin, a phosphatase). This exposes an NLS and possibly masks an NES, resulting in nuclear import and activation of transcription by NF-AT. Decreased Ca+2 leads to re-phosphorylation of NF-AT which inactivates the NLS and re-exposes the NES, causing NF-AT to relocate to the cytosol. Some immunosuppresive drugs act by blocking the ability of calcineurin to dephosphorylate NF-AT and thereby block nuclear transport of NF-AT. April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 26 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 7. Examples from Pathobiology, cont.: C. How HIV-1 exploits cellular machinery for genomic RNA trafficking: • • • 1. Cellular RNAs: almost always exported from the nucleus in a fully spliced form (albeit sometimes spliced in alternate ways), with retention of incompletely spliced RNA in nucleus. Question: why is this important for the cell? 2. But HIV-1 exports incompletely spliced RNA out of nucleus. How? a. HIV-1 produces multiply-spliced mRNAs encoding Tat, Rev, Nef (early proteins); singly-spliced mRNAs encoding Vif, Vpr, Vpu, and Env (regulatory proteins); and an unspliced mRNA encoding Gag & GagPol (late proteins). b. Initially, only multiply-spliced mRNAs are exported out of the nucleus, resulting in translation of Tat, Rev, and Nef. c. Rev is transported back into nucleus, and binds to RRE stem loop present in HIV-1 singly and multiply-spliced genomic RNA retained in nucleus. Rev has an NES that recruits the nuclear export factor Crm1 to the Rev/RRE complex. Thus, Rev acts as a virally-encoded adaptor to mediate nuclear export of genomic RNA via Crm1 pathway, resulting in later expression of regulatory and late proteins. April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 27 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 7. Examples from Pathobiology, cont.: C. How HIV-1 exploits cellular machinery for genomic RNA trafficking, cont.: April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 28 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 7. Examples from Pathobiology, cont.: D. Other retroviruses use a different mechanism to export unspliced genomic RNA: Lentiviruses as well as HTLV-1 use a Rev-like mechanism for Direct binding of CTE in nuclear export of genomic RNA. MPMV genomic RNA to Type D retroviruses and avian type C retroviruses have export receptors structured sequences in their genomic RNAs (the constitutive transport element, or CTE) that binds directly to transport receptors TAP and Nxt, which mediate most mRNA export. Thus, these simple retroviruses bypass the need for a virally-encoded adaptor protein like Rev. Rev interacts with a specific loop in the RRE in the HIV-1 genome via an arginine-rich RNA-binding motif NES Crm1 REV p Ri ab R / NPC incompletely spliced RNA nucleus PM J. Lingappa, 2003 April 4, 2006 Cullen, J. Cell Sci. 116: 587 (2003) J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 29 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 7. Examples from Pathobiology, cont.: E. How nuclear import machinery is exploited by Adenovirus (Ad) for viral entry into the nucleus: J. Lingappa, 2003 April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 30 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 7. Examples from Pathobiology: F. Herpesvirus Egress: Herpesvirus Egress: Herpesvirus capsids assemble in nucleus. Envelopment occurs at inner nuclear membrane. One model gaining favor proposes that capsids then get deenveloped at the outer nuclear membrane resulting in release of unenveloped capsids in the cytoplasm. These capsids acquire a new envelope at the Golgi. Study of mechanism involved in deenvelopment may reveal nature and function of proteins that reside in space between the two nuclear membranes. Currently, mechanism of deenvelopment is not understood. April 4, 2006 From Mettenleiter, J. Virol. 76: 1537 (2002) J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 31 Trafficking In and Out of The Nucleus 8. Additional Reading: • • • • • • • • Cullen, B. R. Nuclear RNA export. J. Cell Science 116: 587 (2002). Bayliss, R. The molecular mechanism of transport of macromolecules through nuclear pore complexes. Traffic 2000 1:448 (2000). Nakielny, S. and G. Dreyfuss. Transport of proteins and RNAs in and out of the nucleus. Cell 99: 677 (1999). Paushkin, et al. The SMN ocmplex, an assemblyosome of ribonucleoproteins. Current Opinion in Cell Bio. 14: 305 (2002). Cullen, B. R. Retroviruses as model systems for the study of nuclear RNA export pathways. Virology 249: 203 (1998). Whittaker, G. and A. Helenius. Nuclear import and export of viruses and virus genomes. Virology 246: 1-23 (1998). Trotman, L. Import of adenovirus DNA involves the nuclear pore complex receptor CAN/Nup214 and histone H1. Nat Cell Biol. 3:1092-100 (2001). Mettenleiter, T. C. Herpesvirus assembly and egress. J. Virol. 76: 1537 (2002). April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 32 • Digitonin: cell membranes that are rich in cholesterol, like PM, are permeabilized, but internal membranes that are low in cholesterol, like nuclear envelope, remain in tact. • • Point out that substrates that traffic in and out of nucleus are FOLDED Nuclear transport is gated: selective transport across the NPC as well as diffusion • Actinomycin D binds to DNA and blocks movement of Pol along DNA April 4, 2006 J. R. Lingappa, Pabio 552, Lecture 3 33