Forum - PBIS

advertisement

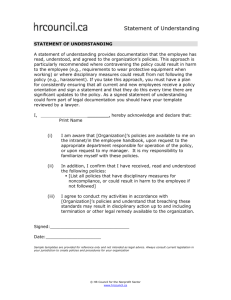

Positive Behavior Intervention Supports (PBIS) Forum “School-Wide PBIS: Implementing a Continuum of Effective Systems & Practices” October 8-9, 2009 Rosemont, Illinois Ensuring Cultural Relevancy in Intervention Gwendolyn Cartledge The Ohio State University Cartledge.1@osu.edu Introduction A letter from a concerned parent A consultation to a concerned assistant superintendent of a large urban district. PBIS resulted in fewer office disciplinary referrals Numbers of referrals for African American males still too high Why minority (African American) males? Research literature: males, regardless of race/ethnicity more likely than females to be identified for disciplinary and special education referrals Assessment instruments for social and problem behaviors give separate gender scales, with more allowances for males than females (e.g., Walker Problem Behavior Scale 22 boys; 12 girls for problem behavior classification) Need to resist overly simplistic explanations such as: 1.Boys are exceptionally bad, or 2. School personnel is racist Issue is quite complex, involving factors such as: Poverty Cultural discontinuities or misperceptions Minority status within the school Academic failure Inadequate classroom management Lack of will to address race or do something different Data from One Elementary School: Frequent Repeaters (Need to recognize what we are doing does not work) 15 or more referrals (16 students) 5-14 referralsm (16 students) 1-4 referrals (9 students) 80 70 Number of office referrals Year 1 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Sep. Oct. Nov. Dec. Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May. Sep. Oct. Nov. Dec. Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May 00 00 00 00 01 01 01 01 01 01 01 01 01 02 02 02 02 02 Month Understanding Gender Ann Arnett Ferguson Bad Boys. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press Classroom Disruption: Display power by disrupting class and calling attention to self • Making noise, noncompliance, joking, talking, etc. Challenges and may even topple authority - particularly if teacher is female Will play for audience - peers more important than adults • Teacher writes: “Whoever taught these students when they were young must have been dumb.” • Student responds: “Oh, I didn’t remember that was you teaching me in the first grade.” • Everyone cracks up. Boys more likely to get attention from the teacher & applause from peers Girls more likely to be sidelined by teachers and peers Fighting: Physical aggression is a “male thing,” viewed as way to solve conflict, do not see themselves as bullies or aggressors Little trust that teachers are able to solve their conflicts “Fighting emblematic ritual performance of male power” - normal social behavior. • Applauded by various cultures • Embraced by academically unsuccessful (Troublemakers) who are socialized to be aggressive, eg., “Don’t let others take advantage of you;” Don’t be a punk.” • Behavior feared by schools and thus, students treated more harshly. (Ferguson) School orientation begins to dwindle at about the 4th grade. Boys begin to seek other means to affirm themselves, perhaps due more to hostile school climate than to peer pressure. (Ferguson) Many African American males at a relatively early age decide that the existing schooling will not enable them to achieve socially desired rewards - nothing to lose. (Noguera) When removal from classroom life begins at an early age, it is even more devastating, as human possibilities are stunted at a crucial formative period of life. Each year the gap in skills grows wider and more handicapping, while the overall process of disidentification … encourages those who have problems to leave school rather than resolve them in an educational setting (Ferguson, p. 230). Cultural Competence Ways in which schools aggravate social adjustment problems of culturally diverse learners: Monocultural curriculum (fail to recognize background of culturally diverse learner) Individualistic/competitive environments Disproportionate disciplinary referrals with harsher penalties More restrictive educational placements Low expectations School personnel need to view themselves as agents of change and should take action in More effective instruction/early interventions More effective classroom management Teaching the desired social behaviors Developing greater cultural competence Culturally responsive disciplined schools are those that Evidence caring, fairness, behavior management, affirmations, social skill instruction, and commitment (Cartledge et al., 2009). Genuinely attempt to involve African American parents in school rather than simply call to express behavior and attendance concerns. (Boyd & Correa, 2005) Some Recommendations Read and discuss some professional works on school age black male culture with references such as the following: • Ferguson, A.A. (2001). Bad boys: Public schools in the making of black masculinity. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan. • Milner, H.R. (2007). African American males in urban schools: No excuses—Teach and empower. Theory into Practice, 46(3), 239-246. • Moore, J.L., & Owens, D. (2009). Educating and counseling African American students: Recommendations for teachers and school counselors. In The SAGE handbook of African American education, L.C. Tillman, Ed. (pp. 351-381). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Make social skill instruction culturally specific by: Selecting skills that are socially valid to the learner. For example, teach students how to express concern appropriately over unfair disciplinary actions. Use the learner’s culture to inform the instruction. Use culturally specific materials such as a workbook by Mychal Wynn (1992) to study specific traits of black males in your classrooms. Conduct series of school-based in-service sessions to review school’s disciplinary policies relative to A. Policy ambiguities B. Fairness of consequences C. Alternatives to suspensions Involve students (including black males with disciplinary histories) in discussions of disciplinary policies to determine fair, equitable procedures. Emphasize student ownership Recommendations con’t Consider innovative projects such as The Father’s Circle as initiated by Montgomery County Schools, Maryland that can be seen at the following link Retrieved July 23, 2009. November-December 2007, http://www.montgomeryschoolsmd.org /departments/itv/ITV_Webcasts_Cover ToCover.shtm References Boyd, B.A., & Correa, V.I. (2005). Developing a framework for reducing the cultural clash between African American parents and the special education system. Multicultural Perspectives, 7(2), 3-11. Cartledge, G., Gardner, R., Ford, D. (2009). Diverse learners with exceptionalities: Culturally responsive teaching in the inclusive classroom. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Day-Vines, N.L., & Day-Hairston, B.O. (2005). Culturally congruent strategies for addressing the behavioral needs of urban, African American male adolescents, Professional School Counseling, 8(3), 236-244. Day-Vines, N.L., & Terriquez, V. (2008). A strengths-based approach to promoting prosocial behavior among African American and Latino students. Professional School Counseling,12(2), 170-175. Ferguson, A.A. (2001). Bad boys: Public schools in the making of black masculinity. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan. Lo, Y., & Cartledge, G. (2007). Office disciplinary referrals in an urban elementary school. Multicultural Learning and Teaching, 2(1), 20-38. Nevarez, C., & Wood, J.L. (2007). Developing urban school leaders: Building on solutions 15 years after the Los Angeles riots. Educational Studies, 42(3), 266-280. Noguera, P.A. (2003). Schools, prisons, an social implications of punishment: Rethinking disciplinary practices. Theory Into Practice, 42, 341-350. Wynn, M. (1992). Empowering African-American males to succeed: A tenstep approach for parents and teachers. Marietta, GA: Rising Sun Publishing Thank You! Gwendolyn Cartledge cartledge.1@osu.edu