Skeletal System

advertisement

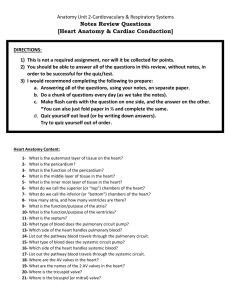

The Heart Chapter 18 Introduction The heart is the pump of our circulatory system The cardiovascular system provides the transport system of the body Using blood as the transport medium, the heart continually propels oxygen, nutrients, wastes, and many other substances into the interconnecting blood vessels that move past the body cells Introduction The heart is a muscular double pump with two functions – Its right side receives oxygen poor blood from the body tissues and then pumps it to the lungs – Its left side receives oxygenated blood from the lungs and then pumps it to the body Introduction The blood vessels that carry blood from the lungs form the pulmonary circuit The vessels that carry blood to all the body tissues form the systemic circuit Heart Size, Location and Position The heart is about the size of a fist It weighs between 250 350 grams (less than a pound) Located in the medial cavity of the thorax, the mediastinum It extends from the 2nd rib to 5th intercostal space Rests on the superior surface of diaphram Heart Size, Location and Position The lungs flank the heart laterally and partially obscure it Heart Size, Location and Position The heart lies anterior to the vertebral column and posterior to the sternum Two thirds of the heart lies to the left of the midsternal line; the balance projects to the right Its broad flat base, or posterior surface, points to right shoulder The apex points toward the left hip Location - 4 Corners The heart is has four corners projected onto the anterior thoracic wall Superior right - where the costal cartilage joins the 3rd rib Superior left - costal cartilage of 2nd rib a fingers breadth lateral to the sternum Location - 4 Corners The inferior right - lies at the costal cartilage of the sixth rib, a finger’s breath lateral to the sternum The inferior left (apex) lies in the fifth intercostal space at the mid-clavicular line These points depict the normal heart size and placement Coverings of the Heart The heart is enclosed in a triple-walled sac called the pericardium The loose fitting outer layer of the sac is the fibrous pericardium – This tough, dense connective tissue layer 1) protects the heart; 2) anchors the heart; and 3) prevents overfilling Coverings of the Heart Deep to the fibrous pericardium is the double-layered serous pericardium, a closed sac sandwiched between the fibrous pericardium and the heart The two layers are… – Parietal layer – Visceral layer Coverings of the Heart The outer parietal layer adheres to the internal surface of the fibrous pericardium At the superior reflection of the heart, the parietal layer is continuous with the visceral layer of the serous pericardium or epicardium Coverings of the Heart The visceral layer, also called the epicardium, is an integral part of the heart wall The two-layer membrane conforms around the heart much like pushing your fist into a double layer membrane with an air pocket in between Coverings of the Heart Between the two layers of serous pericardium is the slitlike pericardial cavity The cavity contain pericardial fluid The serous membranes, lubricated by fluid, glide smoothly against one another during heart activity, creating a relatively friction-free environment Inflammation Inflammation of the heart can lead to serious problems – Pericarditis / hinders production of serous fluid production causing the heart to rub – Cardiac tamponade / inflammatory fluid seep into the pericardial cavity, compressing the heart and limiting its ability to pump blood Layers of the Heart Wall The heart wall is composed of three layers – Superficial layer of epicardium – Middle layer of myocardium – Deep layer of endocardium All three layers are richly supplied with blood vessels Layers of the Heart Wall The epicardium is the visceral layer of the serous pericardium The epicardium is often infiltrated with fat, especially in older people Layers of the Heart Wall The myocardium is the layer of cardiac muscle that forms the bulk of the heart It is the layer that actually contracts The myocardium’s elongated circularly spirally arranged muscle cells squeeze the blood though the heart Layers of the Heart Wall Within the myocardium, the branching cardiac muscle cells are tethered to each other by crisscrossing connective tissue fibers also arranged in spiral or circular bundles These interlacing bundles effectively link all parts of the heart together Layers of the Heart Wall The connective tissue forms a dense network called the internal skeleton of the heart It reinforces the myocardium internally and anchors the cardiac muscle This network of fibers is thicker in some areas than in others to reinforce valves and where the major vessels exit Layers of the Heart Wall The internal skeleton prevents overdilation of vessels due to the continual stress of blood pressure Additionally, since connective tissue is not electrically excitable, it limits action potentials across the heart to specific pathways Layers of the Heart Wall The endocardium is a glistening white sheet of endothelium (squamous epithelium) resting on a thin layer of connective tissue Layers of the Heart Wall Located on the inner myocardial surface, it lines the heart chambers and covers the connective tissue skeleton of the valves The endocardium is continuous with the endothelial linings of the blood vessels leaving and entering the heart Heart Chambers The heart has four chambers Atria – Two superior atria – Two inferior ventricles The longitudinal wall separating the chambers is called the – Interartial septum • Between atria – Interventricular septum Septum • Between ventricles Ventricles Heart Chambers The right ventricle forms most of the anterior surface of the heart The left ventricle dominates the inferioposterior aspect of the heart and forms the heart apex Left Ventricle Right Ventricle Heart Chambers Two grooves visible on the surface of the heart indicate the boundaries of its four chambers and carry the blood vessels that supply myocardium The Atrioventricular groove or coronary sulcus encircles the junction of the atria and ventricles Coronary Sulcus Heart Chambers The anterior interventricular sulcus, separates the right and left ventricles It continues as the posterior interventricular sulcus which provides a similar landmark on the heart’s posterioinferior surface Posterior Interventricular Sulcus Anterior Interventricular Sulcus Heart Chambers Except for the small, wrinkled, protruding appendages called auricles, the atria are free of distinguishing surface features The auricles increase the atrial volume slightly Atria Auricles Heart Chambers Internally, the posterior walls are smooth, but the anterior walls are ridged by bundles of muscle tissue These muscle bundles are called pectinate muscles Pectinate Muscle Heart Chambers The interatrial septum bears a shallow depression, the fovea ovalis This landmark marks the spot where an opening, the foramen ovale, existed in the fetal heart Fovea Ovalis Heart Chambers Functionally, the atria are receiving chambers for blood returning to the heart from the circulation Because they need to contract only minimally to push blood into the ventricles, the atria are relatively small, thin walled chambers As a rule they contribute little to the propulsive pumping of the heart Atria: The Receiving Chambers Blood enters the right atrium via three veins Superior vena cava – Superior vena cava • Returns blood from body regions superior to diaphragm – Inferiorn vena cava • Returns blood from body areas below the diaphragm Coronary – Coronary sinus sinus • Collects blood draining from the myocardium itself Inferior vena cava Atria: The Receiving Chambers Blood enters the left atrium via four veins – Right and left pulmonary veins The pulmonary veins transport blood from the lungs back to the heart Left pulmonary veins Right Pulmonary veins Posterior view Ventricles: Discharging Chambers Marking the internal walls of the ventricle chambers are irregular ridges of muscle called trabeculae carneae The papillary muscles project into the cavity and play a role in valve function Papillary muscles Trabeculae carneae Ventricles: Discharging Chambers The ventricles are the discharging chambers of the heart Note the difference in thickness of the wall When the ventricles contract blood is propelled out of the heart and into circulation Atrial Wall Ventricular Wall Ventricles: Discharging Chambers The right ventricle pumps blood into the pulmonary trunk, which routes blood to the lungs for gas exchange The left ventricle pumps blood into the aorta, the largest artery in the systemic circulation Aorta Left ventricle Right ventricle Pulmonary trunk Pathway of Blood: Heart The heart is actually two pumps, each serving a separate blood circuit Blood vessels that carry blood to the lung form the pulmonary circuit (gas exchange) Vessels carrying blood to the body form the systemic circuit Pathway of Blood: Heart The right side of the heart forms the pulmonary circuit Blood returning from the body enters the right atrium and passes into the right ventricle The ventricle pumps the blood to the lungs via the pulmonary trunk Pathway of Blood: Heart Blood in the pulmonary circuit is oxygen poor and carbon dioxide rich Once in the lungs the blood unloads carbon dioxide and picks up oxygen Freshly oxygenated is carried back to the heart by the pulmonary veins Pathway of Blood: Heart Note that the circulation of the pulmonary circuit is unique Typically veins carry oxygen poor blood to the heart and arteries carry oxygen rich blood The pattern is reversed in the pulmonary circuit with the pulmonary arteries carrying oxygen poor blood to the lungs and the pulmonary veins carrying oxygen rich blood back to the heart Pathway of Blood: Heart The left side of the heart is the systemic system pump Freshly oxygenated blood leaving the lungs enters the left atrium and passes into the left ventricle The left ventricle pumps blood into the aorta and from there into many distributing arteries Pathway of Blood: Heart Smaller distributing arteries carry the blood to all parts of the body Gases, wastes and nutrients are exchanged across capillary walls Blood then returns to the right atrium of the heart via systemic veins and the cycle continues Pathway of Blood: Heart Although equal volumes of blood are flowing in the pulmonary and systemic circuits at any one moment the two ventricles have very unequal work loads The pulmonary circuit, served by the right ventricle, is a low pressure circulation The systemic circuit, served by the left ventricle, circulates through the entire body and encounters about five times as much resistance to blood flow Pathway of Blood: Heart The fact that blood passes through heart chambers sequentially does not mean that the four chambers contract in that order Rather the two atria contract together, followed by the simultaneous contraction of the two venticles Pathway of Blood: Heart A single sequence of atrial contraction followed by the ventricular contraction is a called a heartbeat The heart of the average adult person at rest beats 70-80 times a minute Pathway of Blood: Heart The contraction of a heart chamber is called a systole The time during which a heart chamber is relaxing and filling with blood is termed diastole Although both atrial and ventricular chambers experience systole and diastole the terms usually reference the ventricles which are the dominant heart chambers Ventricles: Discharging Chambers The difference in system work load is revealed in the comparative anatomy of the two ventricles The walls of the left ventricle are three times as thick as those of the right ventricle Left ventricle Ventricles: Discharging Chambers The cavity of the left ventricle is circular The right ventricle wraps around the left and is crescent shaped The left can generate much more pressure than the right and is a far more powerful pump Left ventricle Pathway of Blood: System Blood flows through the heart and other parts of the circulatory system in one direction – Right atrium right ventricle pulmonary arteries lungs – Lungs pulmonary veins left atrium left ventricle body This one way flow of blood is controlled by four heart valves Heart Valves Heart valves are positioned between the atria and the ventricles and between the ventricles and the large arteries that leave the heart Valves open and close in response to differences in blood pressure Tricuspid valve Bicuspid (mitral) valve Aortic valve Pulmonary valve Heart Valves The valves of the heart allow for the blood to flow in only one direction Note: View of the heart with the superior atria removed Atrioventricular (AV) Valves The AV valves are located at each atrial-ventricular junction The valves are positioned to prevent a backflow of blood into the atria when the ventricles are contracting The valves are the – Tricuspid valve – Bicuspid valve Tricuspid valve Bicuspid (mitral) valve Atrioventricular (AV) Valves The right AV valve, the tricuspid, has three flexible cusps The left AV valve, the bicuspid, has two flexible cusps The cusps are flaps of endocardium reinforced by connective tissue Tricuspid valve Bicuspid (mitral) valve Atrioventricular (AV) Valves Attached to each of the AV valve flaps are tiny collagen cords called chordae tendoneae The cords anchor the cusps to the papillary muscles protruding from the ventricular walls Papillary muscles Chordae tendoneae Atrioventricular (AV) Valves When the heart is completed relaxed, the AV valve flaps hang limply into the ventricular chambers Blood flows into the atria and then through the open AV valves into the ventricles Atria contract, forcing additional blood into ventricles Atrioventricular (AV) Valves When the ventricles begin to contract, compressing the blood in the chambers, intraventricular pressure rises forcing blood superiorly against the valve flaps The chordae tendoneae and the papillary muscles anchor the flaps in their closed position Semilunar (SL) Valves The aortic and pulmonary semilunar valves are located at the bases of the large arteries exiting the ventricles The valves prevent backflow of blood from the aorta and pulmonary trunk into the associated ventricles Aortic valve Pulmonary valve Semilunar (SL) Valves Each semilunar valve is made up of three pocketlike cusps Their mechanism of closure differs from that of the AV valves When the ventricles contract intraventricular pressure exceeds the blood pressure in the aorta and pulmonary trunk Semilunar (SL) Valves Blood pressure from the ventricle forces the semilunar valves open and blood is forced past the valve and into the artery When the ventricles relax, and the blood flows backward toward the heart it fills the cusps which closes the valves Heart Sounds The closing of the heart valves causes vibrations in the adjacent blood and heart walls that account for the familiar “lub-dup” sounds of the heartbeat The “lub” is produced by the closing of the AV valves at the start of ventricular systole The “dup” is produced by the closing of the semilunar valves at the end of ventricular systole Fibrous Skeleton The fibrous skeleton of the heart lies in the plane between the atria and the ventricles It surrounds the four valves It is composed of dense connective tissue Fibrous Skeleton The fibrous skeleton has four functions – It anchors the valve cusps – It prevents overdilation of the valve openings as blood pulses through them – It is the point of insertion for the bundles of cardiac muscle in the atria and ventricles – It blocks the direct spread of electrical impulses from the atria to the ventricles Conducting System Cardiac muscle cells have an intrinsic ability to generate and conduct impulses that signal these same cells to contract rhythmically These properties are intrinsic to the heart muscle itself and do not depend on extrinsic nerve impulses Even if all nerve connections to the heart are severed, the heart continues to beat rhythmically Conducting System The conducting system of the heart is a series of specialized cardiac muscle cells that carries impulses throughout the heart musculature, signaling the heart chambers to contract in proper sequence Conducting System The components of the conducting system are: – Sinoatrial node – Internodal fibers – Atrioventricular node – Atrioventricular bundle – Right an left branches – Purkinje fibers Conducting System The impulse that signals each heartbeat begins at the sinoatrial (SA) node This is a crescent shaped mass of muscle cells that lies in the wall of the right atrium, below the entrance of the superior vena cava Conducting System The sinoatrial node, the heart’s own pacemaker, sets the basic heart rate by generating 70-80 impulses per minute Conducting System The sequence that controls each heartbeat - atrial contraction followed by ventricular contraction is specific Conducting System Impulses from the SA node spread in a wave along the cardiac muscle fibers of the atria signaling the atria to contract Conducting System Some of these impulses travel along the intranodal pathway to the atrioventricular (AV) node in the inferior part of the interatrial septum, where they are delayed for a fraction of a second Conducting System After this delay, the impulses race through the atrioventricular bundle which enters the interventricular septum and divides into right and left bundle branches Conducting System About halfway down the septum, the Bundle fibers, (crura), become bundles of Purkinje fibers which approach the apex of the heart, then turn superiorly into the ventricular walls Conducting System This arrangement of conducting structures ensures that the contraction of the ventricles begins at the apex of the heart and travels superiorly, so that the ventricular blood is ejected superiorly into the great arteries The brief delay of the contraction signaling impulses at the AV node enables the ventricles to fill completely before they start to contract Conducting System Because the fibrous skeleton between the atria and ventricles is nonconducting, it prevents impulses in the atrial wall from proceeding directly on to the ventricular wall As a result, only those signals that go through the AV node can continue on Conducting System Examination of the microscopic anatomy of the heart’s conducting system reveals that the cells of the nodes and AV bundle are small, but otherwise typical cardiac muscle cells Each Purkinje fiber, by contrast, is a long row of special, large-diameter cells called Purkinje myocytes Conducting System Purkinje myocytes are cardiac muscle cells containing relatively few myofilaments because they are adapted more for conduction than contraction Their large diameter maximizes the speed of impulse conduction Purkinje fibers are located in the deepest part of the ventricular endocardium, between the endocardium and myocardium layers Innervation Although the heart’s inherent rate of contraction is set by the SA node, this rate can be altered by extrinsic neural controls Innervation The nerves to the heart consist of visceral sensory fibers Parasympathetic fibers that slow heart rate Sympathetic fibers that increase the rate and force of heart contractions Innervation Parasympathetic nerve fibers arise as branches of the Vagus nerve in the neck and thorax Innervation Sympathetic nerves travel to the heart from the cervical and upper thoracic chain ganglia All nerves serving the heart pass through the cardiac plexus on the trachea before entering the heart Innervation Although autonomic fibers project to cardiac musculature throughout the heart, they project most heavily to the SA and VA nodes and the coronary arteries Innervation The autonomic input to the heart is controlled by cardiac centers in the reticular formation of the medulla of the brain In the medulla, the cardio-inhibitory center influences parasympathetic neurons, whereas the cardioacceleratory center influences sympathetic neurons Innervation These medullary cardiac centers, in turn, are influenced by such higher brain regions as the hypothalamus, periaqueductal gray matter, amygdala, and insular cortex Coronary Circulation The coronary circulation, the functional blood supply of the heart, is the shortest circulation in the body The arterial supply of the coronary circulation is provided by the right and left coronary arteries Coronary Circulation The left coronary artery runs toward the left side of the heart and then divides into its major branches Anterior interventricular artery follows the sulcus and supplies blood to the interventricular septum and walls of ventricle Coronary Circulation The right coronary artery courses to the right side of the heart where it divides The marginal artery serves the myocardium of the lateral part of the right side of the heart The posterior interventricular artery runs to the apex of the heart Coronary Circulation There are many merging blood vessels that delivery blood to the heart muscle This explains how the heart can receive an adequate supply when one of its coronary arteries is almost entirely occluded Coronary Circulation The coronary arteries provide an intermittent pulsating flow to the myocardium These vessels and their main branches lie in the epicardium and send branches inward to nourish the myocardium Although the heart represents only about 1/200 of body weight, it requires 1/20 of the body’s blood supply The left ventricle receives the largest proportion of the blood supply Coronary Circulation After passing through the myocardium, the venous blood is collected by the cardiac veins The veins join together to form an enlarged vessel called the coronary sinus which empties into the right atrium End of Material Chapter 18