All - Children's Law Center

advertisement

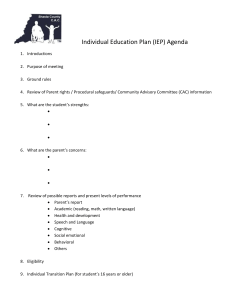

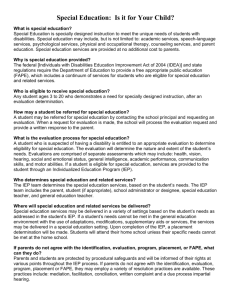

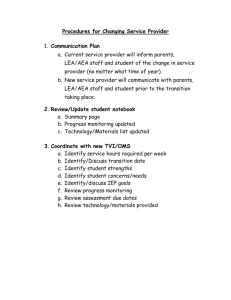

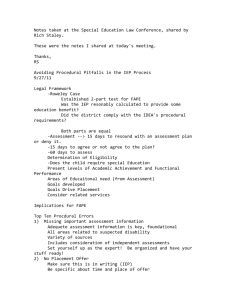

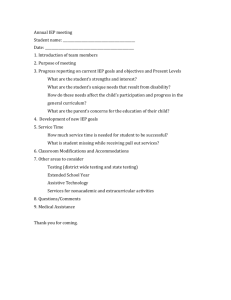

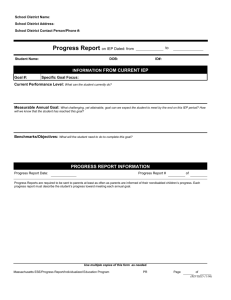

WELCOME Pro Bono Special Education Training February 2016 Introduction Nancy Drane, Pro Bono Director Pro Bono Special Education Training February 2016 Welcome to CLC’s Pro Bono Program • Overview of Children’s Law Center • Special Education Work • Children’s Law Center’s Pro Bono Program • Special Education • Housing Conditions • Custody Guardian ad Litem (CGAL) • Caregiver (Adoption, Guardianship, Custody) • Who are CLC Pro Bono Attorneys? • Why do volunteers work with CLC’s Pro Bono Program? • How CLC Supports its Pro Bono Volunteers • Finding the Right Pro Bono Case Welcome • Agenda for today • Overview of Healthy Together and Handling Special • • • • • • Education Cases Overview of DC’s School System What is Special Education? Handling a Special Education Case The Due Process Hearing Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act Review of Materials, Questions, Potential Cases Other Preliminaries • Review of Handouts • Special Education Manual • Facility Information • Training Evaluations Thank you! Pro Bono Special Education Training February 2016 Children’s Law Center fights so every child in DC can grow up with a loving family, good health and a quality education. Judges, pediatricians and families turn to us to be the voice for children who are abused or neglected, who aren’t learning in school, or who have health problems that can’t be solved by medicine alone. With 100 staff and hundreds of pro bono lawyers, we reach 1 out of every 8 children in DC’s poorest neighborhoods – more than 5,000 children and families each year. And, we multiply this impact by advocating for city-wide solutions that benefit all children. Visit childrenslawcenter.org to learn more. Overview of Healthy Together and Handling Special Education Cases Tracy L. Goodman, Director, Healthy Together Sarah Flohre, Supervising Attorney Pro Bono Special Education Training February 2016 What is a Medical Legal Partnership? • A healthcare delivery model that integrates legal assistance as a vital part of the healthcare delivery system • Expanding the concept of medical care for low income families to include legal representation • Program model based on prevention • Removing non-medical barriers to children and families’ health and wellbeing • Address adverse social conditions negatively impacting health through a variety of modalities • MLPs work to address and prevent adverse social pressures with legal remedies through: • Direct Patient Contact • Provider Training • Systemic Advocacy CLC’s Healthy Together: DC’s Medical Legal Partnership for Children “[D]ramatic differences in …child and adult health outcomes based on social factors such as income and wealth…begin early in life-even before birth-and accumulate over lifetimes and across generations.” Robert Wood Johnson Fdn, Issue Brief Series: Exploring the Social Determinants of Health, March 2011 •Children’s National Health System • One of the oldest MLPs in the country • In 2002 began with one lawyer •In 2015 we now have ten lawyers and two investigators •A variety of Children’s National clinics and programs: •Generations •Four Children’s Health Center Locations •Large focus on teen parents and SE residents •Mary’s Center for Maternal and Child Health • Began in 2010 with grant funding through Mary’s Center’s Healthy Start Healthy Family program • Currently working on a joint program surrounding children and asthma •Unity Healthcare, Minnesota Avenue •Started onsite in April Why Special Education Cases? • • • • • • Filling a community need Hands-on lawyering Direct advocacy Litigation experience Concrete results for children Working with families Children’s Law Center fights so every child in DC can grow up with a loving family, good health and a quality education. Judges, pediatricians and families turn to us to be the voice for children who are abused or neglected, who aren’t learning in school, or who have health problems that can’t be solved by medicine alone. With 100 staff and hundreds of pro bono lawyers, we reach 1 out of every 8 children in DC’s poorest neighborhoods – more than 5,000 children and families each year. And, we multiply this impact by advocating for city-wide solutions that benefit all children. Visit childrenslawcenter.org to learn more. Overview of DC’s School System DCPS, Public Charter Schools, Other Options Tracy L. Goodman, Director, Healthy Together Sarah Flohre, Supervising Attorney Pro Bono Special Education Training February 2016 School Options for DC Kids • • • • • • • • • Home Early Childhood Centers (ages 0-2) Head Start Programs (ages 3-5) Public Schools (Pre-K through 12) Public Charter Schools (Pre-K through 12) Private Schools Residential Facilities Institutions Hospitals Avenues for Enrollment in DCPS Schools • Residence in a Particular Neighborhood • School lottery • http://www.myschooldc.org/ • Application high schools • Transfer (safety transfer or other special transfer) • Placement Decision by Special Education IEP team/school system • Through Hearing Officer Decision (special education) Avenues for Enrollment in Charter Schools • School Lottery: • Most charter schools participate in the common lottery http://www.myschooldc.org/ • A few charters still run their own application/lottery process • Lottery System • May not discriminate against students with disabilities in admission • If over-subscribed, must maintain a waitlist • No uniform way to manage waitlists • By date of application • By lottery • Once lottery is concluded, any open spots are awarded first come, first serve Avenues for Enrollment in Private/Non-Public Schools • DC Opportunity Scholarship Program/Voucher Program • Will not cover the costs of most special education private schools. • Typically covers the costs of parochial schools. • Placement Decision by MDT/IEP team (full time special education school) • Through Hearing Officer Decision (full time special education school) Getting to School Students in DC must get themselves to school (for DCPS or Charter School) UNLESS they qualify for transportation as part of their special education plan or under the Americans with Disabilities Act OR the school provides transportation for all students Public School System Framework • State Education Agency (SEA) • In DC: Office of the State Superintendent for Education (OSSE). • The state school system of the state in which the child resides that oversees all LEAs in the state, see, 20 U.S.C. §1412. • Local Education Agency (LEA) • In DC: District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) or the Independent Charter School (LEA Charter). • Per the Special Education Quality Improvement Act of 2014 (DC Act 20-488), all charters must be their own LEA by Aug. 1, 2017. The exception is any charter where over 90% of the student population is special education (St. Coletta’s PCS) • The local school system of the county, city, or town in which the child resides and oversees the day-to-day delivery of specialized instruction and related services to children with disabilities, see, 20 U.S.C. § 1413. Who Oversees Who… OSSE DCPS DCPS Schools Independent LEA Charters District Charters (until Aug 1, 2017 except St. Coletta’s PCS) Public Charter School Board LEA Status: Who is the LEA? • DCPS Schools • DCPS • Charter Schools • District Charter Schools: Charters that elected to have DCPS as the LEA. No charter will allowed to be a dependent charter after Aug. 1, 2017. • LEA Charter Schools: School is its own LEA • DCPS is not involved in service provision or oversight Why Does it Matter Who the LEA is? • It will dictate with whom you will be advocating • Different LEAs often have different approaches to their legal obligations to children with disabilities • OSSE’s relationship with DCPS as the LEA is different than its relationship with individual LEA Charter Schools (DCMR 5-3019.8 and OSSE policies) • Where DCPS is the LEA, OSSE does not interact directly with particular schools • Where the Charter School is their own LEA, OSSE works directly with the school • Most significant when a change in placement is being contemplated • It does NOT impact legal obligations of the LEA • A single LEA Charter school has the same legal obligation as the 120+ school DCPS system to meet the needs of all children with disabilities Children’s Law Center fights so every child in DC can grow up with a loving family, good health and a quality education. Judges, pediatricians and families turn to us to be the voice for children who are abused or neglected, who aren’t learning in school, or who have health problems that can’t be solved by medicine alone. With 100 staff and hundreds of pro bono lawyers, we reach 1 out of every 8 children in DC’s poorest neighborhoods – more than 5,000 children and families each year. And, we multiply this impact by advocating for city-wide solutions that benefit all children. Visit childrenslawcenter.org to learn more. What is Special Education? Overview of Special Education Law in the District of Columbia Tracy L. Goodman, Director, Healthy Together Sarah Flohre, Supervising Attorney Pro Bono Special Education Training February 2016 What is Special Education? • Specially designed instruction, provided at no cost to the parent, that meets the unique needs of a child with a disability. • Special Education Can Include: • • • • • Travel training Vocational training Specialized Academic Instruction Related services Classroom Accommodations and Modifications • See CFR §300.39 Related Services Can Include: • • • • Speech and Language Therapy Occupational Therapy Physical Therapy Counseling Services/Behavioral Support Services • Transportation Services • Parent Counseling and Training • Medical Services • See 34 CFR §300.34 Accommodations/Modifications and Supplementary Aids and Services: • • • • • • • • Dedicated Aide; Use of Word Processor; Special Seating; Adaptive Furniture; Extra Time for Tests; Breaks during Testing or Class; Testing at Best Time of the Day for the Student; Specified Form for Directions (Repeated, Written, Oral); and • Use of Calculator • See 34 CFR §300.42 Legal Authority • The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEIA) • Title 20 USC § 1400, et seq • Federal Regulations • • 34 CFR Parts 300 and 301 (ages 3-21) 34 CFR Part 303 (ages 0-2) • Local Regulations • District of Columbia Municipal Regulations, Title 5 • Three New Local Laws • • • Enhanced Special Education Services Amendment Act of 2014, D.C. Act 20487 Special Education Quality Improvement Act of 2014, D.C. Act 20-488 Special Education Procedural Protections Expansion Act of 2014, D.C. Act 20-486 • OSSE Special Education Student Hearing Office Due Process Hearing Standard Operating Procedures Manual (SHO SOPM) • Policies promulgated by OSSE and DCPS (e.g. Policies and Procedures for Placement Review) What is the IDEIA? • The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act is a federal statute that is meant to ensure that all children with disabilities receive a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment (LRE) • Children ages 0 to 22 are covered by the IDEIA • Part C of the IDEIA covers children ages 0 through 2 • Part B of the IDEIA covers children ages 3 through 21 Key Term: Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) • Special education and related services: • Provided at no charge to the parent under public supervision and direction; • Meets the standards of the State Education Agency (OSSE); • Designed to meet the individual needs of the child to ensure the child makes educational progress; • Are provided in conformity with the child’s Individualized Education Program (IEP). • See 20 USC §1401(9); 34 CFR §300.17 • A child’s educational progress cannot be trivial or de minimus Key Term: Child Find • DC must ensure that all children with disabilities or suspected of having a disability, residing in the city (or who are wards of the city) and who are in need of special education and related services are identified, located, and evaluated • Applies regardless of the severity of the child’s disability • Includes children who are: • • • • Not attending school; Homeless; Wards of the District (committed to CFSA or DYRS); Attending Private Schools and Public Charter Schools • See 20 USC §1412(a)(3); 34 CFR §300.111 Key Term: Individualized Education Program (IEP) “[Congress envisioned] the IEP as the centerpiece of the [IDEA]’s education delivery system for disabled children.” Honig v. Doe, 484 US 305 (1987) • A written statement for each child with a disability that is developed, reviewed, and revised in accordance with the IDEIA (20 USC §1414(d)) • The plan governing what a child in special education should be receiving as part of his/her education • See 20 USC §1401(14); 34 CFR §300.22 Key Term: Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) • To the maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities are educated with children who do not have disabilities in a regular education classroom; and, • Children with disabilities should attend their neighborhood school unless that school does not have the kind of program that can meet their special needs • See 20 USC §1412(a)(5); 34 CFR §300.114 Steps to Obtain Special Education 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Referral Evaluation Eligibility Determination IEP Development Placement Determination IEP Review Re-Evaluation Step 1: Referral • In order to be evaluated for special education and related services, a child with a suspected disability must first be referred for evaluations • A child must be referred by: • • • • Parent Employee of school system; Adult child; or Employee of another state agency (e.g. CFSA, DBH) • See 20 USC §1414(a); 34 CFR §301(b) How are Referrals Made? • Referrals should be made in writing to the school system or principal • Referrals should include: • Date of the referral; • Simple statement of educational concerns of the child and why you think child has a disability; • Statement requesting evaluations and special education service; and • Signature and contact information of person making the referral. • Referrals for children ages 0-3 should be made to OSSE for Early Intervention • Referrals for children ages 3-5 should be made to Early Stages What Happens Once a Referral is Made? • The school must hold an MDT/IEP meeting after the referral is made and before conducting evaluations • At the meeting, the school should: • Review current information and data about the child and any pre-referral interventions; • If further evaluations are needed, develop a Student Evaluation Plan (SEP) detailing the reasons for the referral and the evaluations to be conducted; • Explain to the parent what evaluations are to be conducted; and • Obtain informed consent from the parent of the child (See 20 USC § 1413(a)(1)(D); 34 CFR § 300.9) Multidisciplinary Team/IEP Team • MDT/IEP team must include: • • • • The parent(s); Special education teacher; Individual who can interpret evaluation results; Other persons at the discretion of parent or LEA, who have knowledge or special expertise regarding the child; • The child, if appropriate; and • Representative of LEA who is: • Knowledgeable about general curriculum of LEA; • Knowledgeable about the availability of resources of LEA; and • Qualified to provide or supervise the provision of special education • See 34 CFR §300.321 Step 2: Evaluation • The LEA is responsible for conducting a comprehensive and individualized evaluation to determine: • Whether a child is a child with a disability, and • The educational needs of the child • See, 20 USC §1414(b); 34 CFR §300.304 • DC Code allows the school 120 days to complete initial evaluations • Trumps IDEIA, which provides for 60 days in the absence of state rules to the contrary • As of July 1, 2017, the DC timeline will be 60 days. Common Types of Evaluations: Psychological • Names of Psychological Evaluations: • Psycho-educational Evaluation - conducted by a psychologist • Clinical Psychological Evaluation - conducted by a psychologist • Comprehensive Psychological Evaluation - conducted by a psychologist • Neuropsychological Evaluation - conducted by a neuropsychologist; for children who have an underlying neurological disorder, including autism. • Three main areas of testing • Cognitive/Intelligence • Social-emotional • Academic testing • School Psychologist vs Clinical Psychologist: • School psychologists only need to have a masters and be licensed by OSSE • Clinical psychologists are PsyDs and have state licensure to practice • School evaluations will give classifications from IDEIA • IEEs by clinical psychologists will give DSM-IV classifications • Psychiatric Evaluation • conducted by an MD psychiatrist • IDEIA permits this type of evaluation, but schools rarely do it and refer out • Not a good alternative to a psychoeducational—should be conducted in conjunction with it Common Types of Evaluations: Related Services • Speech and Language Evaluation • Physical ability to produce speech • Expressive and receptive language • Occupational Therapy Evaluation • Fine motor skills • Sensory differences • Physical Therapy Evaluation • Gross motor skills • Assistive Technology Evaluation • Looks at whether any technology can assist the student’s educational functioning • Functional Behavioral Assessment • Series of observations to determine the root causes and triggers of a student’s problematic behaviors • Used to create a behavior intervention plan Step 3: Eligibility Determination • Once all evaluations are completed, the school must convene another MDT/IEP meeting • Meeting is to review the evaluations • Meeting must include someone who can interpret evaluation data • The MDT/IEP team must determine if the child: • Is a child with a disability as defined in the IDEIA; and • If that disability impacts the child in the school setting such that they require specialized instruction and related services • See 20 USC §1414(b)(4); 34 CFR §300.306 Eligibility Determination • When making this determination, the MDT/IEP team must review the evaluations and other relevant information, such as: • • • • • Existing evaluations provided by the parent; Information provided by the parent; Assessments conducted in the classroom; State and local assessments of the child; and Observations of teachers and related service providers • See 20 USC §1414(c)(1) Disabilities Under the IDEIA • • • • • • • • Autism Deaf-Blindness Deafness Developmental Delay Emotional Disturbance Hearing Impairment Intellectual Disability Multiple Disabilities • • • • • • Orthopedic Impairment Other Health Impairment (includes ADHD, HIV/AIDS, etc.) Specific Learning Disability Speech and/or Language Impairment Traumatic Brain Injury Visual Impairment (Including Blindness) What if a Parent Disagrees? • The parent has a right to request an Independent Educational Evaluation (IEE) to be paid for by the LEA • • • Parent only need express their disagreement with the LEA’s evaluation and request funding for an independent evaluation Parent can disagree with the LEA’s decision not to evaluate or not to comprehensively evaluate The LEA may request additional information on the disagreement • After a request for an IEE, the LEA has two choices under the law • Provide funding authorization for an IEE without unnecessary delay • File a due process complaint against the parent to prove the appropriateness of their evaluation • 34 CFR §300.502 Step 4: Development of an IEP • The IEP is developed by the MDT/IEP team • The IEP must include: • The child’s present level of performance; • Information on how the child’s disability affects his/her involvement and progress in a general education setting; • Measurable annual goals and objectives; • Levels and types of special education, related services, supplementary aids/services and program modifications; • An explanation of the extent to which the child will not participate with nondisabled children in the regular class; and • Any accommodations required in the classroom and for standardized testing • See 20 USC §1414(d) Other Important IEP Components • Transportation • Extended School Year (ESY) • Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP) (See 34 CFR § 300.324(a)(2)(i)) • Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) should be done first • Transition Plan (See 34 CFR § 300.43) • Required for child ages 14 and over (since March 2015 special education legislation) • Should be developed after a vocational evaluation • Includes a transition services plan and age-appropriate goals relating to: • • • • Training; Education; Employment; and Independent Living Skills, if appropriate Step 5: Placement • Meeting convened with the IEP/MDT team • Can be separated from or folded into an IEP meeting • Placement is based on the individual needs of the child, and must consider: • • The IEP; and LRE requirements • Placement is made by a group of people, including: • • The parent, and Other persons knowledgeable about the child, the meaning of the evaluation data, and placement options • Placement must be determined at least annually • Placement must be as close as possible to the child’s home • See 34 CFR §300.116; 20 USC §1414(e) Continuum of Placements • Instruction in General Education Classes • Inclusion/Push-in Services by special education provider • Instruction in Special Classes • • Pull out classes in academic subjects or for related services Ranges from one or two classes to the bulk of a child’s school day • Special Schools • • • Educational placement where a child spends all day in a special education setting with special education peers. No contact with regular education peers during the day Can be a public school or a non-public school • Home Instruction • Instruction in Hospitals and Institutions • • Residential programs are for kids unable to function in the community Children with disabilities in residential programs must be able to access their specialized instruction • See, CFR §300.38 and § 300.115 Step 6: IEP Review • IEPs must be reviewed and revised as necessary, but at least once a year • A parent or school can request an IEP meeting at anytime if there is concern about the provision of FAPE to the child • For example: • Child is regressing in academic or behavioral areas • Child has begun to act out • Child has made excellent progress and goals need to be adjusted • See 20 USC §1414(d)(4) Step 7: Re-Evaluation • A child who receives special education services must be re-evaluated in all areas of suspected disability every 3 years unless all members of the team agree that it is not necessary • • A school may not unilaterally make the decision not to evaluate Team’s decision not to evaluate should be documented • A child can be re-evaluated more frequently at the request of the parent or teacher • School must also re-evaluate child “as conditions warrant” • • • Sudden change in school performance Significant event in child’s life (death of parent, trauma) impacting school performance See 20 USC §1414(a)(2); 34 CFR §300.303(b)(2) Procedural Requirements for the Provision of FAPE • The LEA must provide parents: 1. A copy of the Procedural Safeguards 2. The opportunity to review their child’s educational records; 3. The opportunity to meaningfully participate in IEP development and placement decisions; 4. The opportunity to obtain an independent educational evaluation; 5. Prior Written Notice when proposing or refusing to initiate or change the provision of FAPE to the child (now including a change in educational location); 6. The opportunity for mediation; and 7. The opportunity to file a Complaint • “Stay-put” rights until the complaint is resolved Prior Written Notice (PWN) Must Include: • A description of the action proposed or refused by the agency; • An explanation of why the LEA proposes or refuses to take the action; • A description of each evaluation procedure, record, or report used as a basis for the action; • A description of other options considered by the IEP team and the reason why those options were rejected; and • A description of the factors that are relevant to the LEA’s proposal or refusal • See 20 USC §1415(c) Troubleshooting Denial of FAPE Procedural Issues • • • • • • Timeline Violations Notice to parents Parent Involvement IEP team participants IEP implementation Timely Evaluations Substantive Issues • • • • • • Meaningful Progress IEP Implementation Appropriate instruction Appropriate evaluations LRE Appropriate educational placement • Appropriate teachers and therapists A Procedural Violation = Denial of FAPE When: • It impedes the child’s right to a FAPE; • It significantly impedes the parent’s opportunity to participate in the decisionmaking process regarding the provision of a FAPE to the child; or • It caused a deprivation of education benefits to the child HARM • See 20 USC § 1415(f)(3)(E)(ii) Discipline: Suspensions and Expulsions • Students with disabilities have special protections in disciplinary matters • Can still be suspended, but depending on number of days, school must follow certain procedures • A student with a disability is always entitled to a FAPE and can never be excluded from receiving an education • These protections cover children with disabilities who have not yet been found eligible for special education if: • The school system knew or should have known that the child is a child with a disability through parent or teacher referral • See, 34 CFR §300.534 Extra Protections for Students with Disabilities • Excluding a child with disabilities from class for more than 10 school days is a change in placement. • • Therefore, the school must hold a meeting to determine whether the behavior is a manifestation of the student’s disability This meeting must take place whether it’s been 10 consecutive days or 10 days throughout one school year • If it is a manifestation, and/or is a result of the school’s failure to provide appropriate services or implement the child’s IEP, then the suspension/exclusion cannot take place What is a Manifestation Determination? • A meeting of the child’s IEP team to determine if the behavior that lead to the disciplinary action is substantially related to the child’s disability • The IEP team must convene within 10 school days to determine if: (i) If the conduct in question was caused by, or had a direct and substantial relationship to, the child's disability; • This is NOT whether the child knows right from wrong or, (ii) If the conduct in question was the direct result of the LEA's failure to implement the IEP. (iii) DCPS also considers if the IEP was appropriate • The Team must review and consider all relevant info, including: • Evaluations • Observations of the child • Information provided by the parent • Current IEP and placement See, 34CFR §300.530 Manifestation Determination: Results • If the team answers “yes” to any of those questions, the behavior is deemed to be a manifestation of the child’s disability and the disciplinary action must be rescinded. • There is an exception for incidents where child had dangerous weapon, drugs, or caused serious bodily injury • In addition, the school must: Conduct an FBA and create/implement a BIP Review a BIP already in existence and modify it as necessary Permit the child to return to their previous placement, unless team agrees there should be a change in placement 34 CFR §§300.530 through 300.536 20 U.S.C. 1415(k)(1) and (7) And if a Parent Disagrees? • Expedited Due Process Hearing is always available • DCPS Students • DCMR regulations apply to DCPS students (not DCPS-LEA charter school students) (DCMR Title 5, Chapter 25) • Disciplinary hearings available for suspensions over 10 days • Other types of advocacy may be possible • Charter School Students (even DCPS) • No DCMR regulations exist for charters but they do have to follow the IDEIA disciplinary provisions • Charters set their own disciplinary policies, and many do not have clear policies • Limited appeals may be possible Children’s Law Center fights so every child in DC can grow up with a loving family, good health and a quality education. Judges, pediatricians and families turn to us to be the voice for children who are abused or neglected, who aren’t learning in school, or who have health problems that can’t be solved by medicine alone. With 100 staff and hundreds of pro bono lawyers, we reach 1 out of every 8 children in DC’s poorest neighborhoods – more than 5,000 children and families each year. And, we multiply this impact by advocating for city-wide solutions that benefit all children. Visit childrenslawcenter.org to learn more. Handling a Special Education Case From First Contact Through Advocacy Development Tracy L. Goodman, Director, Healthy Together Sarah Flohre, Supervising Attorney Pro Bono Special Education Training February 2016 Client Realities: Representing Parents Housing Education Violence Immigration Finances Family Health Insurance Disability Child Care Food Other Issues that May Be Impacting Clients 2015 POVERTY GUIDELINES FOR THE 48 CONTIGUOUS STATESAND THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Persons in Poverty guideline family/household For families/households with more than 8 persons, add $4,160 for each additional person. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 $11,770 15,930 20,090 24,250 28,410 32,570 36,730 8 40,160 • Income • Your client may work • BUT many wage jobs do not allow time off to attend meetings, answer calls, etc. • Even very low wage employment cuts families off from much state assistance, adding financial pressures on the family • Your client may not work • May have young or needy children requiring their full attention • May have a disability of their own • Public Benefits • • • Certification and recertification processes can be arduous Do not cover the cost of raising and feeding a family Housing is often unsafe, unsanitary, and unstable Other Issues that May Be Impacting Clients • Education • Your client may not: • Have graduated from high school • Have basic literacy skills • Have been provided the information they need to advocate for their children • Other Stressors • Your client may: • Have responsibilities for extended family members, neighbors, etc. • Have to rely on public transportation • Not to be safe in his or her home or neighborhood Implications: Client Interactions • Barriers to communication via phone or face to face: • • • • • Inflexible job Transportation Costs Time commitment for using public transportation Caring for an infant or other relative Cost of cell phone minutes • Client may come to you frustrated and confused • Frustrated with the school, and sometimes the child him or herself • May not understand everything that is happening to his/her child or how to fix it • May be overwhelmed by other stressors Implications: Communication • Make sure your client knows how to contact you • Send a letter with your name, address, phone number, and e-mail • Find out all possible ways to contact your client • Some client’s contact information may change during representation, make sure your client knows to keep you up to date • At the end of the month, client’s cell phones may be shut off—try again at the beginning of the month • Ask for the phone number of a friend, family member, or other person who can be a back-up contact Implications: Communication • In written and spoken correspondence, always use regular language your client can access and understand • Check in consistently (e.g. “did I explain that okay?”) • Thoroughly explain verbally anything you send to your client in writing • Try to keep written communication at an eighth grade level • Many programs allow you to check literacy levels • Discuss how you and your client will stay in regular communication early in your representation First Steps When you take a special education case from Children’s Law Center, you will receive all the information and every document we were able to gather during our intake process. 1. You will receive an intro email from your mentor once you notify us conflicts check is complete • CLC will each out to your client to notify them 2. Contact the client as soon as possible to schedule initial meeting • Ask them to update you on anything that happens with the school, including if the school wants to schedule a meeting • Consider transportation and logistical challenges for the client • Consider whether client needs funds to get to your office Initial Client Meeting: The Basics • Sign retainer and release in the initial meeting • Review and sign the retainer • Get client to sign a release of information • You will want to explain what it means to work with a lawyer • Confidentiality • The relationship (e.g. the client is the “boss”) • Long and short term goals • Importance of staying in contact • Use simple language—don’t use legalese or abbreviations! • Discuss who will communicate with the school about requests for meetings, evaluations etc. • Be explicit about when you want them to contact you • • • Any contact from school Before signing anything Training manual has some suggested topics for the first meeting in Tab 1 Deciding on an Advocacy Strategy • Adversarial vs. Collaborative approaches • Much of the work will be informal advocacy, even if you are going to litigation • Why Collaborative? • Client may want child to continue at the school • School may be cooperating and some other entity (ie: DCPS central office) is the main issue • School may give you more information • Why Adversarial? • Headed directly into litigation • School has completely alienated your client • You need to go straight to “litigator” mode Common First Steps: Requesting Records • Requesting records • Request school records from the Special Education Coordinator (“SEC”) or school registrar • Request medical or mental health records as needed • You should request to inspect and copy the records at the school’s expense or to have the school send a copy to you. Common First Steps: Requesting an IEP Meeting • Requesting an IEP meeting is a typical first step for either an adversarial or collaborative case • How to request the meeting: • In writing to the special education coordinator or director of special education • You can be specific in your email/letter about what you want to meet about to ensure the correct personnel are there General Tips on IEP Meetings • Meetings are often led by the special education coordinator • But, you should feel free to add the “purpose” of the meeting • Discuss how you will communicate with your client and who will speak during the meeting • • • • You are creating a “record” but there is no recording and usually no notes by the school. You can tape record if you want. If you are going to litigation, you may want a paralegal/third party present. Follow up in writing (again, hearsay is admissible and you put the school on notice). New Legislative Changes • The Special Education Student Rights Act of 2014 (DC Act 20-486) in effect since March 10, 2015 requires: • LEA shall provide the parent with any evaluations, assessment, report, data chart or other document to be discussed at an IEP meeting no fewer than 5 business days before the IEP meeting • LEA shall provide parent with a copy of the amended or new IEP no later than 5 business days after the meeting where changes were made. If a final copy is not available, then the LEA must provide the latest available draft IEP and then a final copy no later than 15 business days after it was agreed upon. What happens at an IEP Meeting to improve the IEP? • IEP meetings are run differently at every school • But, the general course of most is: 1. Introductions and review of the purpose of the meeting • Feel free to add to the purpose of the meeting 2. Review of how the child is doing by teachers/service providers 3. Review of Evaluations (if relevant) 4. Discussion of issues raised by parent or school • Attendance • Grades/credits • Specific issues with the IEP What happens at an IEP meeting in an eligibility case? 1. First meeting: Student Evaluation Plan and Consent to Evaluate • • 2. The team must agree which evaluations are needed The parent must provide written consent Second Meeting: The team must meet within 120 days to review the evaluations and determine eligibility • • • Evaluators will review evaluations and give the opportunity to ask questions Team will determine if the child qualifies for special education If the team determines: • • • 3. The child qualifies for special education, then they will create an IEP The child has a disability, but would be better served by a 504 plan—refer to 504 team The child is not eligible for either, then the parent can object and/or request IEEs Second or Third Meeting: Creation of the IEP • • • Ensure that there are adequate services in the appropriate setting Ensure that appropriate modifications are in place Discuss placement What happens at an IEP meeting in an IEE case? 1. First Meeting: Request IEE • • • This may be accomplished in writing with the school without a meeting If the school does not respond to your request, you will want to contact DCPS Central Office Once you have the authorization, we can make referrals for evaluators 2. Provide IEE to the school • Be sure to document when you gave it to the school 3. IEE Review Meeting • • • • IEE evaluator typically does not attend the meetings School will need time to review the evaluations prior to the meeting DCPS will require that their staff write a summary and determine if DCPS accepts or rejects the IEE This meeting may be very positive with the school or you may be setting up for litigation What happens at an IEP meeting for placement? • Very dependent on what type of school • But, the general course of most is: 1. Introductions and review of the purpose of the meeting • Feel free to add to the purpose of the meeting 2. Review of how the child is doing by teachers/service providers 3. Discussion of type of placement needed • • School may agree more restrictive placement is needed School may disagree—then you will need to start building your case Placement in a DCPS LEA Case • If the team agrees that a more restrictive placement is needed, DCPS’ Least Restrictive Environment (sometimes called “Location Review”) team will be called in. • Often, the LRE team will meet without the parent or any members of the IEP team • If the team agrees that a new location of services is needed, DCPS’ placement team will be called in. • Again, this team does not often meet with the IEP team or the parent • The parent can accept the proposed placement or can litigate for a different placement. • We do not think this is a legal process and we recommend that you create a record of disagreement with this process. Placement in a LEA Charter Case • If team agrees that a more restrictive placement is needed AND the Charter can not provide it, the team will do a referral to OSSE. • OSSE’s placement team will meet with the school and with the IEP team • OSSE will issue a state recommendation • OSSE will issue a location of services letter within ten days of the IEP meeting with OSSE • This is a big advocacy opportunity to drive the school selection. Post-Meeting Strategy • In all situations, you should consider a follow up letter to the school outlining: • • • • Key things from the meeting Anything you believe the school agreed to do Any outstanding issues Any issues you were not able to raise at the meeting Other Advocacy Strategies to Consider: DCPS Cases 1. Contact DCPS Central Office • Most helpful for issues around IEEs or compensatory education • Case compliance officer for the school (public schools) • LEA progress monitor for the school (non-publics) • Carla Watson, Director of Compliance and Resolution 2. Contact the Instructional Superintendent • Most helpful for issues around discipline, bullying or transfers between DCPS schools 3. Contact the central office 504 Specialist • Colin Bishop Litigation Cases • For cases you anticipate will go to litigation: • Obtain all school records • And maintain a set as the school gave it to you in case there is a disagreement about whether you were provided all records • Get copies of classwork/homework from your client • Document everything • Get read receipts on emails/fax confirmations • Consider bringing in an expert to observe the child at school and to advise you Using Experts • Attorneys often find an expert helpful to help them determine next steps, appropriateness of an IEP and placement issues. • Types of experts: • • • • • Psychologists (often evaluators) Speech-language, occupational therapy or physical therapy experts Psychiatrists Counselors Educational expert (often former long-time special education teachers and administrators) • Why retain an expert? • • • • Parent has burden of proof Expert opinion is sometimes necessary to prove issues raised in your case Experts can help in understanding child’s needs Discussion of appropriateness of proposed remedy Costs of Experts • Expert costs are variable • Expectation is that Firm will pay cost of experts • Cost Example: Educational Experts • • Often retained to an independent evaluation of educational need From $5000-$10,000 for investigation and hearing. • Evaluators: • • • Independent Educational Evaluations (IEEs) authorized by the LEA are paid by the LEA at pre-determined rates Firm may pay cost of evaluation if no IEE or if IEE rates do not cover cost of preferred evaluator Evaluators will typically charge an additional fee to testify, if needed • Hourly fees for testimony range widely • Special Education Student Rights Act of 2014 (DC Act 20-486): • For cases filed after July 1, 2016, reasonable expert witness fees may be sought in many cases. Special Education Student Rights Act of 2014 • Special Education Student Rights Act of 2014 (DC Act 20-486) in effect since March 2015, has improved access to school observations • Requires that LEA’s: • Shall provide timely access to any current or proposed special education program to: • the parent of a child with a disability • to a designee appointed by the parent who has professional expertise in the area of special education being observed or is necessary to facilitate an observation of a parent or to provide language translation assistance to a parent • Includes other important protections for observations DCPS Observation and Visitor Policy • But, schools may still request experts to sign documents limiting ability to observe CLC Recommendations: • If your expert or evaluator is presented with a document to sign that limits their ability to observe, or report on observations, please have them: 1. 2. 3. Sign their name at the bottom and write underneath their signature, “my signature on this agreement is subject to the attached addendum.” This addendum is available in the pro bono practice manual. Sign the addendum and date it Make sure to get copies of the two documents together (the school will keep the originals, but ask for a copy for their files). • Please notify us if your expert is presented with an addendum or similar document DCPS Observation and Visitor Policy Text of the CLC-recommended addendum: I am conducting an independent educational evaluation of [CHILD’S FULL NAME] to assist with the provision of special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEIA). I understand that the attached Confidentiality Agreement is not intended to interfere with the rights afforded by the IDEIA to children with disabilities or their parents. To the extent required under the IDEIA, as soon as possible upon completion of my observation and report, I agree to provide said report of any recommendations or observations I made regarding the above-referenced student and the student’s classroom/school environment to the District of Columbia Public Schools. _____________________________ NAME Date ____________________ Children’s Law Center fights so every child in DC can grow up with a loving family, good health and a quality education. Judges, pediatricians and families turn to us to be the voice for children who are abused or neglected, who aren’t learning in school, or who have health problems that can’t be solved by medicine alone. With 100 staff and hundreds of pro bono lawyers, we reach 1 out of every 8 children in DC’s poorest neighborhoods – more than 5,000 children and families each year. And, we multiply this impact by advocating for city-wide solutions that benefit all children. Visit childrenslawcenter.org to learn more. The Due Process Hearing: Overview of the Process, Practice Tips, and Litigation Skills Tracy L. Goodman, Director, Healthy Together Sarah Flohre, Supervising Attorney Pro Bono Special Education Training February 2016 Types of Cases that are Commonly Litigated • Cases against DCPS/DCPS dependent charter school rather than an independent charter school • Eligibility cases • IEE cases • Placement cases • These cases frequently proceed to a due process hearing Due Process Hearings Due Process hearings play out over a very short timeline – just 75 days from the day you file to the day you receive a hearing officer decision. • Special education cases are litigated administratively • The “trial” is called a due process hearing •Petitioner bears the burden of proof •Independent Hearing Officers are contracted to hear Petitioner claims •In DC Hearing Officers contract with, but do not work for, OSSE • In DC Hearing Officers directly control other aspects of case management Burden of Proof • Currently, the Petitioner bears the burden of proof and persuasion unless an HO orders otherwise. • Once fully in effect, the Special Education Student Rights Act of 2014 (DC Act 20-486) will require: • Where there is a dispute about the program or placement the child is in or one which is proposed by the school: • If the petitioner bears the burden of production and establishes a prima facie case; then, • the public agency shall have the burden of persuasion on the appropriateness of the program or placement. • Becomes effective for all due process complaints filed after July 1, 2016 Filing a Complaint • Who can file? Complaints should include basic facts, a list of legal issues and general proposed remedies. • Parents can file a complaint regarding any matter relating to the provision of a free and appropriate public education • LEA can also bring a complaint against the parent in certain circumstances • Parent refuses to consent for initial evaluation or re-evaluation • Parent has requested an IEE and the school wants to defend its own evaluation • Child over 18 who has educational rights can file on his/her own behalf What can you file about? • Any denial of FAPE against the student by the LEA or SEA you are naming in your complaint • Alleged violations must have occurred not more than 2 years before the date the filing party knew or should have known about the alleged action forming the basis for the complaint • There are statutory and case law exceptions to the statute of limitations Litigation Options • When filing, you can choose: • Mediation only • Mediation and a due process hearing • Note that mediation tolls the timeline for the due process hearing • Due process hearing only • Expedited due process hearing • Motion required, even if automatic entitlement Expedited Due Process Hearings • When Can a Hearing be Expedited? • Automatic application when the complaint concerns certain discipline matters. • At the discretion of the hearing officer if the physical/emotional health or safety of the student or others is in danger; or • At the discretion of the hearing officer if there is other substantial justification • What is the Expedited Hearing Timeline? • Within 20 School Days of filing: Hearing must be held • 3 Business Days before hearing: Disclosures Due • Decision must be issued within 10 School Days of hearing What Remedies are Available? • Any remedy that can address the denial of FAPE is possible. • Prospective remedies include: • Placement • Increased services on the IEP • Addition of services/accommodations on the IEP • Retrospective remedy is called compensatory education Compensatory Education • Compensatory Education (Comp Ed) is the term for the remedy for past denial(s) of FAPE • In DC, compensatory education must place the child where s/he would have been but for the LEA’s failure to provide FAPE • Cannot be an hour for hour plan unless there is proof that the plan is specifically crafted for the child’s needs • Key case: Reid v DC, 401 F.3d 516 (2005) • Comp Ed can include anything the child needs, including: • • • • • • Tutoring Speech and language/physical therapy/occupational therapy services Mental health services Transition services Mentoring Technology and software Compensatory Education • For the time period in question: Consider some key questions to ensure your case in chief supports a compensatory education award • • • What should the IEP have looked like? What level of services should have been in place? What should the placement have offered? • Had everything been appropriate, where would the child be: • • • Academically, Socially and emotionally, and/or Functionally • What does the child need to be put in the place they would have been, but for the denial of FAPE? • • What evidence do you have to support your claim? Is their precedent that supports a novel comp ed request? What happens after you file? Resolution Period (Days 1-30) • Day 10: Deadline to file response • There are statutory requirements for what the response must contain if no prior written notice was issued • Day 15: Deadline for school to convene the Dispute Resolution Session/Resolution Meeting Session. • The LEA’s attorney often does not attend. • This is NOT confidential per the statute • Day 30: End of Resolution Period unless waived earlier by parties What happens after you file? Litigation Period (Days 31-75) • Prehearing Conference: Convened by phone to discuss: • • • • • Issues raised and responses More specifics on relief requested Expected witnesses Determine which legal issues will be heard at the hearing Length of hearing and dates of hearing • Prehearing Order: Hearing Officer will issue a Prehearing Order that sets the parameters of the hearing. You must make written objections within 3 days. What happens after you file? • Motions: You can file any motion until the 5-day disclosure deadline. Oppositions to motions are due within 3 business days of the filing of the motion. • 5-day Disclosures: All proposed written evidence and a letter with a witness list and short proffers about testimony is due 5 business days before the hearing. This is served simultaneously by both sides. You generally cannot include any other documents at the hearing. Practical Things about the Hearing • Where? • OSSE Office of Dispute Resolution (“ODR”) • 810 First Street, NE, 2nd Floor, Room 2001, Washington, DC 20002 • The Hearing: • Conducted like a regular trial with openings, Petitioner’s case, Respondent’s case, closings. • EXCEPT: • The whole proceeding is conducted while seated around a conference table • All documentary evidence in the Disclosures is admitted at the beginning of the hearing unless there is an objection • Hearsay is admissible • Witnesses may testify by phone After the Hearing • The Hearing Officer will issues a written Hearing Officer Decision by the 75-day deadline and usually within 10 days of the hearing. • You can submit post-hearing filings • Some HO’s allow/prefer written closings • Sometimes you want to brief a specific area of law to create your record • Appeals are to the DC District Court (D.D.C.) • Have 90 days from the date of the HOD being issued to appeal • Appeals are heard on a mixed standard of review (court can hear it de novo) • Must be admitted to the D.D.C. bar to file an appeal in D.D.C. Children’s Law Center fights so every child in DC can grow up with a loving family, good health and a quality education. Judges, pediatricians and families turn to us to be the voice for children who are abused or neglected, who aren’t learning in school, or who have health problems that can’t be solved by medicine alone. With 100 staff and hundreds of pro bono lawyers, we reach 1 out of every 8 children in DC’s poorest neighborhoods – more than 5,000 children and families each year. And, we multiply this impact by advocating for city-wide solutions that benefit all children. Visit childrenslawcenter.org to learn more. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 504 Plans at School Tracy L. Goodman, Director, Healthy Together Sarah Flohre, Supervising Attorney Pro Bono Special Education Training February 2016 Why are we talking about 504 plans? • 504 plans are an increasingly common way to get interventions for children in school, especially where they are not eligible for special education or are not yet receiving special education. What is Section 504? • The Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504 is a broad civil rights law which protects individuals with disabilities in any agency, school or institution receiving federal funds from discrimination and establishes their right to have the opportunity to fully participate with their peers. • Regulations create affirmative obligations for schools that accept public funding for students with disabilities of mandatory school age • Schools are required to provide a FAPE • In DC, school is mandatory from age 5 (kindergarten) through age 18. • For younger students who attend a public elementary school, the regulations are slightly less clear, but can be argued that they also are entitled to a FAPE. • 34 C.F.R. 104.31-.39 Who is Protected? • Section 504 covers qualified students with disabilities who attend schools receiving Federal financial assistance. • To be protected under Section 504, a student must be determined to: • • • Have a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities; or • Schools are not allowed to consider “mitigating measures” (e.g. medication, hearing aids, etc.) when considering whether a child is eligible. Have a record of such an impairment; or Be regarded as having such an impairment. • A Major Life Activity can include: • • • • • Caring for oneself Performing manual tasks Walking, seeing, hearing, speaking, breathing Learning Working What does the law require of schools? • Provide a free appropriate public education (FAPE) to qualified students in their jurisdictions with a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. • FAPE through Section 504 is generally defined the same as under IDEIA (case law) • Schools must take steps to identify and plan for educating students with disabilities. Consequently, they must: • • • Conduct Evaluations Develop a plan Provide protections (e.g. disciplinary protections) • Schools must eliminate barriers that would prevent a student with a disability from participating fully in the programs and services being offered to peers. • Schools must provide reasonable accommodations and supports to allow the child to participate in the general curriculum and program Evaluations under Section 504 • Districts are required to evaluate students with a suspected disability • • • Tests must be tailored to measure the student’s aptitude and achievement. Generally are less comprehensive than special education evaluations A doctor’s diagnosis, without proof of substantial limitation on the student’s ability to learn or another major life activity, is not sufficient • Parent must consent to initial evaluations • Re-evaluations must be conducted before a significant change of placement. • An exclusion from an educational program for more than 10 days is considered a significant change in placement. • In all other cases, re-evaluations must be conducted “periodically” • • No specific time frame The Law encourages using the IDEIA time frame to meet the requirement Content of the Plan • Regular education teachers/social workers often implement 504 plans • Can include: • • • • • • Medical interventions/services (e.g. nursing services) Behavior interventions Accommodations Modifications Transportation Services: OT, PT, SLT, specialized instruction Development of the Plan • There is no set team of people, but typically includes: • • • • Parents Teacher(s) Evaluator School nurse • Parental consent is NOT required to implement a plan • Parental participation is NOT required to create or revise subsequent plans Legal Protections • All districts must provide procedural rights information to parents • Must include notice, an opportunity to review relevant records and access to an impartial hearing • All districts must have a dispute resolution/hearing mechanism • • Each LEA operates their appeals process differently. Some LEA’s have failed to create a proper appeals process. • Disciplinary protections for children who are eligible for Section 504 are the same as for children who are eligible for the IDEIA • Manifestation determination must be held for a child who has been suspended or otherwise excluded from class for 10 days in a single school year When are 504 Plans Used in Practice? • Where the child has a disability and needs accommodations but does not require special education services such as: • Child with allergy needs classroom accommodations (e.g., nut-free environment) • Child with ADHD needs to be allowed to doodle or do other work to avoid being disruptive • Child in a wheelchair requires elevator access and bus transportation Grievance Procedures • DCPS has a written grievance procedure, but it is not meaningful in terms of relief for the child. – See 25 DCMR §2405 • Most charter schools have no formal written procedures • OSSE will not intervene in these cases • This means that going to federal court may the only real option if a child has a 504 plan that is not being implemented IEP vs. 504 Plan • With an IEP, the parent and child has more legal protections and more direct legal remedies • With an IEP, it is generally easier to get services in place • Schools often takes the position that they are not required to provide services under 504 • This is because there is no federal funding for 504 plans but there is funding for special education services More Information • DCPS 504 Coordinator: • Colin Bishop, colin.bishop@dc.gov • The federal Department of Education Office of Civil Rights has great information: • http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/504faq.html • OSSE has also provided guidance to LEA’s on their obligations under Section 504 • osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/publication/attachments/OSS E_DSE_Section 504_Toolkit 08 28 12.pdf Children’s Law Center fights so every child in DC can grow up with a loving family, good health and a quality education. Judges, pediatricians and families turn to us to be the voice for children who are abused or neglected, who aren’t learning in school, or who have health problems that can’t be solved by medicine alone. With 100 staff and hundreds of pro bono lawyers, we reach 1 out of every 8 children in DC’s poorest neighborhoods – more than 5,000 children and families each year. And, we multiply this impact by advocating for city-wide solutions that benefit all children. Visit childrenslawcenter.org to learn more.