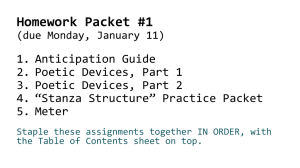

The basic meter of English poetry is iambic: two

advertisement

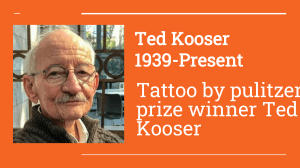

THE TONE LIST Here is a list of tones that students may find in poems. It is not comprehensive, and students should be encouraged to add to it as needed; as the teacher, you should also feel free to trim it to suit your students and class level. Keep in mind that the longer the list is, the more nuanced and powerful your students’ emotional vocabulary will be. abashed bristling disrespectful horrified provocative solemn abrasive brusque distracted humorous questioning somber abusive calm doubtful hypercritical rallying stern ref lective straightforward acquiescent candid dramatic indifferent accepting caressing dreamy indignant reminiscing stentorian acerbic caustic dry indulgent reproachful strident resigned stunned admiring cavalier ecstatic ironic adoring childish entranced irreverent respectful subdued affectionate child-like enthusiastic joking restrained swaggering aghast clipped eulogistic joyful reticent sweet allusive cold exhilarated languorous reverent sympathetic amused complimentary exultant languid rueful taunting angry condescending facetious laudatory sad tense anxious confident fanciful light-hearted sarcastic thoughtful apologetic confused fearful lingering sardonic threatening apprehensive coy flippant loving satirical tired approving contemptuous fond marveling satisfied touchy arch conversational forceful melancholy seductive trenchant ardent critical frightened mistrustful self-critical uncertain argumentative curt frivolous mocking self-dramatizing understated audacious cutting ghoulish mysterious self-justifying upset awe-struck cynical giddy naïve self-mocking urgent bantering defamatory gleeful neutral self-pitying vexed begrudging denunciatory glum nostalgic self-satisfied vibrant bemused despairing grim objective sentimental wary benevolent detached guarded peaceful serious whimsical biting devil-may-care guilty pessimistic severe withering bitter didactic happy pitiful sharp wry blithe disbelieving harsh playful shocked zealous boastful discouraged haughty poignant silly bored disdainful heavy-hearted pragmatic sly brisk disparaging hollow proud smug Abandoned Farmhouse By Ted Kooser Analysis of Literary Techniques He was a big man, says the size of his shoes on a pile of broken dishes by the house; a tall man too, says the length of the bed in an upstairs room; and a good, God-fearing man, says the Bible with a broken back on the floor below the window, dusty with sun; but not a man for farming, say the fields cluttered with boulders and the leaky barn. A woman lived with him, says the bedroom wall papered with lilacs and the kitchen shelves covered with oilcloth, and they had a child, says the sandbox made from a tractor tire. Money was scarce, say the jars of plum preserves and canned tomatoes sealed in the cellar hole. And the winters cold, say the rags in the window frames. It was lonely here, says the narrow country road. Personification: “say the rags” Something went wrong, says the empty house in the weed-choked yard. Stones in the fields say he was not a farmer; the still-sealed jars in the cellar say she left in a nervous haste. And the child? Its toys are strewn in the yard like branches after a storm--a rubber cow, a rusty tractor with a broken plow, a doll in overalls. Something went wrong, they say. Ambiguity: “Something went…” Ted Kooser, "Abandoned Farmhouse" from Sure Signs: New and Selected Poems. Copyright © 1980 by Ted Kooser. Reprinted by permission of University of Pittsburgh Press. Source: Sure Signs: New and Selected Poems (Zoland Books, 1980) On this and the following pages, fill out the empty boxes, using the Analysis of Literary Techniques vertical box (to comment on USAGE of technique by the poet) and the Poetry Terms (to define the techniques being used). Place the comments next to the line…as in the examples above. Ambiguity: Definition The Snappy Guide to Scanning a Poem Adapted by Dr. K from materials at http://www.english.bham.ac.uk/staff/tom/teaching/firstyear06/howtoscan.htm and http://www.amittai.com/prose/meter.php Note: This Guide is heavily based on, and deeply indebted to, Stephen Fry's excellent book, The Ode Less Travelled, which anyone interested in poetry should read. It also draws from John Hollander’s Rhyme’s Reason, an equally informative and entertaining book. If you’ve grown up on a steady diet of free verse, it probably comes as a nasty surprise to you that not all poetry in English is written that way. Robert Frost told the students at Milton Academy in 1935 that “Writing free verse is like playing tennis with the net down,” and many poets before and since have chosen to meet the challenge of meter and rhyme when creating their works. Part of being an English major (and taking the GRE subject exam, etc., etc.) is learning how to “scan” a poem—that is, to determine its meter and its rhyme scheme. In doing so, you’ll gain insight not only into what the poet wanted to emphasize in the poem but also be able to connect it to other works (by the poet and others) in the same metrical and prosodic forms, helping you to place a poem in its historical period and circumstances. So learning to play poetic “tennis” by mastering meter and rhyme is a big part of your development as critical readers of literature. Let’s look at the two main areas separately, starting with meter. Name that foot The basic meter of English poetry is iambic: two syllables to a foot. That’s part of our Indo-European language heritage, since Indo-European featured short syllables as building blocks for words. Note that the names follow a consistent pattern: an adjective describing the shape of the foot or basic stress pattern, and a noun telling you how many feet are in a line. Thus, iambic pentameter tells you that you have five iambs in your line. Pretty simple, once you know what the feet are. And since there only a handful of stress patterns, once you get them down, you just have to count the syllables in the line and you’re in business. OK, so what do these funny words mean? The basic six sound patterns in English have names of Greek etymology and look like this: iamb (_ /) _ /_ / _ /_ / _/ / _ / _ The falli out of fait frie ren is of love ng hful nds, ewi ng trochee (/ _) /_ /_ / _ /_ Double, double toil and trouble anapest (_ _ /) _ _ /_ _ / _ _/ I am monar of all I survey ch dactyl (/_ _) / _ _ /__ Take her up tenderly spondee pyrrhic -and the / whit e / brea st (/ /) (_ _) -of the / dim / sea