The First Industrial Revolution

advertisement

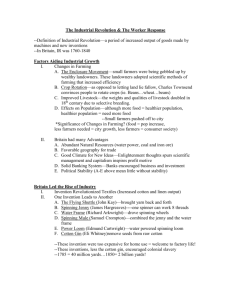

The Industrial Revolution Great Britain 1760-1860 Western European GDP per capita in 1990 International Geary-Khamis dollars (Source: Maddison, 2005) 25,000 Dollars per capita 20,000 15,000 10,000 5,000 0 1 1000 1500 1600 1700 1820 1850 1870 1913 1950 1970 2003 Great Britain—the first industrial nation • 1780-1860---Great Britain has the first Industrial Revolution • 1860/1870-1914---Industrialization spreads to the Continent of Europe. New technologies and industries---differs from first wave • 1914-1918: World War I • 1919-1939: Interwar Period, Uneven Recovery and Growth and the Great Depression • 1939-1944: World War II • 1945-1970: The European Miracle • 1970-1980/1990: Stagflation and Uneven Growth • 1990s-present: Renewed Growth First Industrial Revolution 1. Substantial Rise in Per Capita Incomes 2. Technological Innovation in Production 3. Sectoral Shift: Change in the Economic Structure 4. Population Triples 5. Urbanization 1. The Rise in Per Capita Incomes • • • • Unprecedented 1781 £11 per capita for Great Britain 1861 £28 per capita for Great Britain 155% increase in 80 years---no historical parallel. • What is happening? 2. Technological Innovation in Manufacturing • Rapid rise in productivity in key (high tech) sectors – Textiles (especially cotton) – Iron – Steam---for transportation (railroads and steamships) and production (Steam-powered iron machinery used in textiles and other industries. • Change in Organization of Production – Previously craft and home production of manufactures – Factories (British: mills) appear—workers concentrated in one location – Increase in size of factories—economies of scale 3. Sectoral Shift—Change in Economic Structure • Date GDP£M Agr% Man&Min% • 1770 130 45% 24% 31% • 1861 668 18% 37% 44% Serv&Trans% • Note: real GDP growing at about 2% a year 4. Population Boom • • • • Population of Great Britain (millions) 1701 6.8 million 1781 8.9 million (increases at 0.3% p.a.) 1861 23.2 million (increases at 1.2% p.a.) 5. Urbanization • Proportion of British Living in Cities of 50,000 or more • 1801 14% (1.5 m) of 10.7 m (75% in London) • 1861 25% (5.8 m) of 23.2 m (50% in London) • Rise of cities in northern England and Scotland--Liverpool, Birmingham, Sheffield, Lancaster, Glascow……. But, Wait!! How can population grow and incomes grow? Wasn’t Malthus right? An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798) Everyone Believed Him ? The smartest economists believed him: David Ricardo and Adam Smith Simple Model: (1) equilibrium? (2) technological innovation? (3) harvest failure? Real Wage Population Real Wage Births W0 Deaths Demand for Labor Population Birth Rate, Death Rate Diminishing Returns WHY? Output 10 acres of land or 10 machines 150 With five workers, Q/L = 20 With 10 workers, Q/L = 15 100 5 10 Number of Workers Technological Change---oxen to horses, or horse shoes or two to three field rotation? Output 150 100 5 10 Number of Workers But final outcome? Real Wage 1st Population Real Wage Births W1 Deaths 2nd Demand for Labor Population Birth Rate, Death Rate BUT…..in Great Britain, something happens that’s different • • • • • • • • 1781 8.9 million 1861 23.2 million An increase of 160% 1781 £11 per capita for Great Britain 1861 £28 per capita for Great Britain An increase of 155% or 1.2% a year What explains this unparalleled change? Y = A(L, K, N); Y/L = A(K/L, N/L) what’s driving the growth? K?, L?, A? • Year • 1771 Y p.c.(£) L (m) K(£ m.) K/L(£) 11 • 1861 28 • Increases of • 155% 3.9 670 170 10.8 2770 256 177% 240% Really? 50% How do we measure the effects of an increase in capital or any other factor? Output How to Measure?? 150 100 5 10 Number of Workers Cobb-Douglass Production Function: the standard approach • Y = A(L, K, N) Need a specific functional form • Y = Lα Kβ Nγ where markets are perfectly competitive and each factor is paid the value of its marginal product. The coefficients determine the income share of each factor in GDP. • α+β+γ=1 • Where α = wL/Y, β = iK/Y, γ = rN/Y • For Great Britain in this period • 0.46 + 0.41 + 0.13 = 1 A little differentiation----or why we force you to learn more math for economics • Y = ALα Kβ Nγ • dY = dLαLα-1 AKβNγ + dKβKβ-1 ALαNγ + dNγNγ-1 ALαKβ + dALα Kβ Nγ • dY = dLαLα-1 KβNγ + dKβKβ-1 LαNγ + dNγNγ-1 LαKβ + dALα Kβ Nγ Y ALαKβNγ ALαKβNγ ALαKβNγ ALαKβNγ • dY = dLα+ dKβ + dNγ + dA Which means? Y L K N A • Y/L = A(K/L)β (N/L)γ becomes • d(Y/L) = d(K/L)β+ d(N/L)γ + dA (N/L) (Y/L) (K/L) A Which means? From the data then….Growth Rates and Contributions • Annual Growth Rate • Income per capita 1.17% • Capital per worker 0.30% Share Contribution 0.41 • Land per worker -1.26% 0.13 • So……d(Y/L) = d(K/L)β + d(N/L)γ (N/L) (Y/L) (K/L) 0.12% -0.16% • 1.17 - (0.30).41 - (-1.26).13 = 1.19 = dA/A • We calculate it as a residual What might we call this effect? Malthusian effect? Why does a one time technological innovation not change society’s fate? Technological Change • Y = ALα Kβ Nγ • d(Y/L) = d(K/L)β+ d(N/L)γ + dA (N/L) (Y/L) (K/L) A • 1.17 - .41(0.30) - .13(-1.26) = 1.19 is the Residual • Technological change—also known as the “Solow Residual.” • Result of the exercise: Technological change is what accounts for most of the income growth during the industrial revolution!! Where does technological innovation come from? • The whole economy or the leading sectors? • Huge leaps in “high tech”---huge fall in cost of producing cotton textiles, price declines by 90% 1780-1860. • T.S. Ashton’s student: “About 1760 a wave of gadgets swept over England.” • Major question today when we are in the third great wave of technological innovation. • Micro-inventions (apply to very specific production process---or Macro-inventions (applicable across many production processes) • Steam engine? Gas Engine? Electric Motor? Computer? • • • • • • • • • • • “New” U.S. Economy of the 1990s Gordon’s (2000) estimates of productivity growth: 1870-1891: 0.39% 1890-1913: 1.14%. 1913-1928: 1.42% 1928-1950: 1.90% Golden Age of GP Tech 1950-1964: 1.47% 1964-1972: 0.89% 1972-1979: 0.16% 1979-1988: 0.59% 1988-1996: 0.79% 1995-2000: 1.35% he attributes wholly to the computer-IT sector. Can decompose each industry. 1.19 = 2.6(.07) + 1.8(.035) + 0.9(0.2) + ……. Measured by productivity exercise for the individual industry .52/1.19 = 44% Open the technological black box: Textile Technology—4 processes 1. Preparation of raw material. Cotton, wool, linen or silk. Sorting, cleaning, combing, carding, so fibers lie in same direction 2. Spinning into yarn. Loose fibers and pulled (drawn) and twisted into yarn 3. Weaving. Yarn is used to form warp and then interwoven with the weft. 4. Finishing. Fulling to fuse warp and weft, sizing, shearing, bleaching, dying, printing Traditionally Prior to the Industrial Revolution: Limited Innovations in Medieval Europe • Italy---machines for “throwing” silk and twisting it into thread. • England—Fulling mills with big wooden hammers. • But no concentrated technological change. First Leading (High Tech) Sector: Cotton A Cluster of Inventions • A new fiber in 1700…very little production in Europe, mostly imported from India • Not regulated---no guild production, no tariffs in England (Banned in France)---can experiment • Characteristics: cotton is tough and resilient, elastic with long fibers that can withstand and pulling twisting First Leading Sector: Cotton • The importance of sequencing and bottlenecks • Production of textiles very labor intensive. Population and demand up, prices up • 1733 John Kay invented the fly-shuttle, which allowed the shuttle to move more quickly across the loom. • Slow adoption, but spread by 1750s and 1760s. • Only improves weaving—creating a bottleneck in spinning-----high wages, benefit to spinsters. Flying Shuttle Key Invention for Spinning of Cotton • 1770 Hargreaves patented a spinning jenny. • Machine turned by hand but still more uniform and hence better quality • Linked to Arkwright’s (1771) water frame—it became water powered. • Hand Spinning---one strand of yarn at a time • Hand Powered Spinning Jenny---6 to 24 strands • Spinning Jenny powered by water frame--several hundred strands at one time. Adirondacks (19th century) & Afghanistan (2006) Spinning Jenny and Water Frame Weaving of Cotton • Now a bottleneck in weaving • Golden age of hand loom weavers. High wages for skills 1770-1800. • 1787 Cartwright invents the power loom. • Factories (Mills) are located near “fall line” places where rivers drop fast. • Later steam powered frees factory locations. • By 1833 a man and a child assistant in a cotton factory produced 20 times output of handloom weaver A Weaver’s Song “Come all you cotton weavers, your looms you may pull down, You must get employed in factories, in country or in town, For our cotton masters have found out a wonderful scheme, These calico goods now wove by hand, they’re going to weave by steam.” Diffusion • Year • Spindles Handlooms Power Looms (millions) (thousands) (thousands) • 1820 7 240 14 • 1860 30 3 400 Power Loom • By 1811 U.K. Census reported 100,000 factory workers in spinning mills and 250,000 handloom weavers. Total British labor force 5.5 million. So, 1% of labor force contributes 5% of GDP Growth of the Industry Value of Raw Cotton (millions of lbs) 1760 1800 1820 1860 3 54 141 1050 Value of Cotton Goods (£ millions) 1 11 29 77 Prices Drop • 1780s a “piece” or bolt of cotton cloth sold for 70-80 shillings, by 1850s, it sold for 5 shillings----huge new market---elasticity of demand with this supply shift. • Jules Michelet (19th century France): “prices fell, they went on falling until cotton cloth stood at six sous. Then something completely unexpected occurred. The words six sous aroused the people. Millions of purchasers—poor people— who never bought anything began to stir. Then we saw what an immense and powerful consumer the people are when they are engaged.” Jules Michelet, Le Peuple “The great and fundamental revolution has been in cotton prints. It as required the combined efforts of science and art to force rebellious and ungrateful cotton fabrics to undergo every day so many brilliant transformations and to spread them everywhere within the reach of the poor. Every woman used to wear a blue or black dress that she kept for ten years without washing, for fear it might tear to pieces. But not her husband, a poor worker, covers he with a robe of flowers for the price of a day’s labor. All the women of the people who display and iris of a thousand colors on our promenades were formerly in mourning.” The Manufacture of Iron • The object in iron manufacture is to mix the appropriate amounts of the elements iron and carbon • Iron is obtained from iron ore that has a variety of impurities • Carbon is obtained from wood that has been turned into charcoal or from coal that has been “coked.” • Traditional production of relatively small quantities in a blacksmith’s furnace or larger quantities in a blast furnace • Mix ore and carbon and put into crucible that will be heated by bellows forcing extra oxygen to heat the fire. Production of Iron • Mix ore and carbon and put into crucible that will be heated by bellows forcing extra oxygen to heat the fire. • Result is Pig Iron. Hard metal that is too brittle to work. • Pour molten pig iron into molds for Cast Iron Useful for cannons and fireplaces. Hard but brittle • Pig iron is re-heated and hammered repeatedly, which eliminates some impurities and makes it less brittle---result is Wrought Iron • More malleable but not that strong, but result can be uneven in quality. • Most iron goods---tools and horseshoes Labor intensive, costly process Innovation • Charcoal used until 1709 when Darby makes it commercially feasible to produce high quality coke. • Britain has very large reserves of coal and diminishing forests, but even by 1780 over half of iron made with charcoal. • Major advances in 1783 and 1784. Henry Cort invents “rolling and puddling.” Alternately heating and cooling pig iron until one can squeeze out dross (impurities or slag). Rolled and Puddled Steel • “Rolling and Puddling” requires huge human physical effort. • Makes iron bars, rails, beams— useful for industry, construction, and transport. • Iron is superior to wood, withstands more speed and pressure Growth of Iron Production • British Production • Year Coal • (millions of tons) Pig Iron (1000 tons) • 1800 • 1860 250 4,152 11 80 Steam Engine • Until the steam engine---only human, animal, water or wind power. Last two limits the location. • In 1712, Thomas Newcomen invented the an atmospheric engine---known as the Newcomen engine. First practical steam engine. • Simple piston and pump. Steam not used to drive piston but only to create a vacuum. Ordinary air pressure provided the force that pushed the piston downwards against the weight of the pump at the other end of the beam. • Largely used to pump water out of mines. But it was expensive to operate and huge fuel consumption. • http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newcomen_steam_engine Age of Steam—James Watt • Watt’s steam engine, designed 1769 and first applied 1776 • Has a separate condenser and saves the energy that had previously been dissipated in reheating the cylinder at each stroke now pushes piston back. • Consumes a quarter of the fuel. • Rapid improvement. • Newcomen’s engine requires 100 lbs of coal for one hour of one horsepower---Watt’s engine requires 7 ½ lbs for one hour by 1850. Application to Transportation etc. Stockton & Darlington Railroad 1825 Organization of Production • Home production or Craft production of manufactures. • Most specialty manufactures—textiles, metals, books……produced by specialists who were members of guilds that received a charter from city or Crown. • Professional associations restricted entry--masters, journeymen and apprentices & set quality and sometimes prices • Guilds lose protection of Crown during English Civil War, but remain strong on the continent. “Putting-Out System” • Division of Labor---takes advantage of free time of peasants between planting and harvest seasons and lower wages than guilds • Merchants---manage flow of materials between specialized households. • Merchants buy raw wool and deliver it to households that card and spin it, they pick it up and deliver it to households that weave it, they pick it up and transfer to households that bleach or dye or print the cloth. • Problems? • Remedy? Rise of the Factory • No worker wants to leave home for factory. • If tools cost little, they will have their own • Technological innovation—machines more expensive and larger. • Must move to factories. • Factories allow employers to monitor and discipline workers to avoid shirking and theft. • Textiles first specialize in one function—spinning or weaving, but soon there is vertical integration--receive raw cotton and produce finished cloth. • Adds to growth of urbanization. British cotton mill, power looms in operation, 1830s