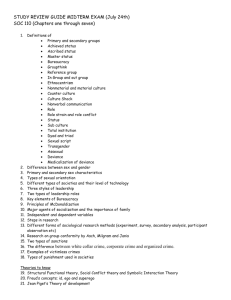

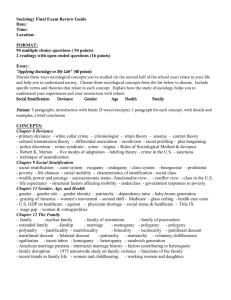

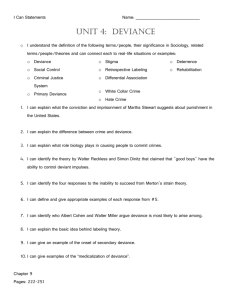

Lecture 10: Introduction to Sociology

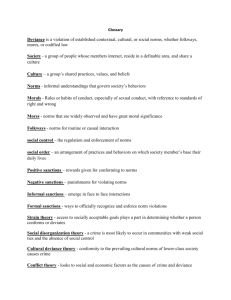

advertisement