document

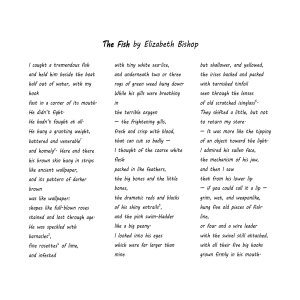

advertisement

1 Poetry Packet Part I: Tone Randall Jarrell The Death of a Ball Turret Gunner From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze. Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life, I woke to black flack and the nightmare fighters. When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose. Judith Ortiz Cofer Back When All Was Continuous Chuckles Doris and I were helpless on the Beeline Bus laughing at what was it? “What did the moron who killed his mother and father eat at the orphan’s picnic? “Crow?” Har-har. The bus was grinding towards Hempstead, past the cemetery whose stones Doris and I found hilarious. Freaky ghouls and skeletons. “What did the dead man say to the ghost?” “I like the movie better than the book.” Even “I don’t get it” was funny. The war was on, rationing, sirens. Silly billies, we poked each other’s arms with balled fists, held hands and howled at crabby ladies in funny hats, dusty feathers, fake fruit. Doris’ mom wore this headgear before she got the big C which no one said out loud. In a shadowy room her skin seemed gray as moon dust on Smith Street, as Doris’ house where we tiptoed down the hall. Sometimes we heard moans from the back room and I helped wring out cloths while Doris brought water in a glass held to her mother’s lips. But soon we were flipping through joke books and writhing on the floor, war news shut off back when we pretended all was continuous chuckles, and we rode the bus past Greenfield’s rise where stones, trumpeting angels, would bear names we later came to recognize. Katharyn Howd Machan Hazel Tells LaVerne last night im cleanin out my howard johnsons ladies room when all of a sudden up pops this frog musta come from the sewer swimmin aroun an tryin ta climb up the sida the bowl so i goes ta flushm down but sohelpmegod he starts talkin bout a golden ball an how i can be a princess me a princess well my mouth drops all the way to the floor an he says kiss me just kiss me once on the nose well i screams ya little green pervert an i hitsm with my mop an has ta flush the toilet down three times me a princess 2 Martin Espada Latin Night at the Pawnshop The apparition of a salsa band Gleaming in the Liberty Loan Pawnshop window: Golden trumpet, silver trombone, congas, maracas, tambourine, all with price tags dangling like the city morgue ticket on a dead man’s toe. Paul Laurence Dunbar To a Captious Critic Dear critic, who my lightness so deplores, Would I might study to be prince of bores, Right wisely would I rule that dull estate— But, sir, I may not; till you abdicate. Part II: Diction/ Figurative Language Philip Levine and Terry Allen Corporate Head They said I had a head for business They said to get ahead I had to lose my head. They said be concrete & I became concrete. They said, go, my son, multiply, divide, conquer. Dorothy Parker Unfortunate Coincidence By the time you swear you’re his, Shivering and sighing, And he vows his passion is Infinite, undying— Lady, make a note of this: One of you is lying. 3 Carl Sandburg Window Night from a railcar window is a great, dark soft thing Broken across with slashes of light. Philip Larkin A Study of Reading Habits When getting my nose in a book Cured most things short of school, It was worth ruining my eyes To know I could keep cool, And deal out the old right hook To dirty dogs twice my size. Later, with inch-thick specs, Evil was just my lark: Me and my cloak and fangs Had ripping times in the dark. The women I clubbed with sex! I broke them up like meringues. Don’t read much now: the dude Who lets the girl down before The hero arrives, the chap Who’s yellow and keeps the store, Seem far too familiar. Get stewed: Books are a load of crap. Sharon Olds Sex Without Love How do they do it, the ones who make love without love? Beautiful as dancers, gliding over each other like ice-skaters over the ice, fingers hooked inside each other's bodies, faces red as steak, wine, wet as the children at birth whose mothers are going to give them away. How do they come to the come to the come to the God come to the still waters, and not love the one who came there with them, light rising slowly as steam off their joined skin? These are the true religious, the purists, the pros, the ones who will not accept a false Messiah, love the priest instead of the God. They do not mistake the lover for their own pleasure, they are like great runners: they know they are alone with the road surface, the cold, the wind, the fit of their shoes, their over-all cardiovascular health—just factors, like the partner in the bed, and not the truth, which is the single body alone in the universe against its own best time. 4 Part III: Title Peter Meinke (Untitled) This is a poem to my son Peter whom I have hurt a thousand times whose large and vulnerable eyes have glazed in pain at my ragings thin wrists and fingers hung boneless in despair, pale freckled back bent in defeat, pillow soaked by my failure to understand. I have scarred through weakness and impatience your frail confidence forever because when I needed to strike you were there to hurt and because I thought you knew you were beautiful and fair your bright eyes and hair but now I see that no one knows that about himself, but must be told and retold until it takes hold because I think anything can be killed after awhile, especially beauty so I write this for life, for love, for you, my oldest son Peter, age 10, going on 11. John Updike Dog’s Death She must have been kicked unseen or brushed by a car. Too young to know much, she was beginning to learn To use the newspapers spread on the kitchen floor And to win, wetting there, the words, "Good dog! Good dog!” We thought her shy malaise was a shot reaction. The autopsy disclosed a rupture in her liver. As we teased her with play, blood was filling her skin And her heart was learning to lie down forever. Monday morning, as the children were noisily fed And sent to school, she crawled beneath the youngest's bed. We found her twisted and limp but still alive. In the car to the vet's, on my lap, she tried To bite my hand and died. I stroked her warm fur And my wife called in a voice imperious with tears. Though surrounded by love that would have upheld her, Nevertheless she sank and, stiffening, disappeared. Back home, we found that in the night her frame, Drawing near to dissolution, had endured the shame Of diarrhoea and had dragged across the floor To a newspaper carelessly left there. Good dog. 5 Sharon Olds The Fish I caught a tremendous fish and held him beside the boat half out of water, with my hook fast in a corner of his mouth. He didn't fight. He hadn't fought at all. He hung a grunting weight, battered and venerable and homely. Here and there his brown skin hung in strips like ancient wallpaper, and its pattern of darker brown was like wallpaper: shapes like full-blown roses stained and lost through age. He was speckled and barnacles, fine rosettes of lime, and infested with tiny white sea-lice, and underneath two or three rags of green weed hung down. While his gills were breathing in the terrible oxygen --the frightening gills, fresh and crisp with blood, that can cut so badly-I thought of the coarse white flesh packed in like feathers, the big bones and the little bones, the dramatic reds and blacks of his shiny entrails, and the pink swim-bladder like a big peony. I looked into his eyes which were far larger than mine but shallower, and yellowed, the irises backed and packed with tarnished tinfoil seen through the lenses of old scratched isinglass. They shifted a little, but not to return my stare. --It was more like the tipping of an object toward the light. I admired his sullen face, the mechanism of his jaw, and then I saw that from his lower lip --if you could call it a lip grim, wet, and weaponlike, hung five old pieces of fish-line, or four and a wire leader with the swivel still attached, with all their five big hooks grown firmly in his mouth. A green line, frayed at the end where he broke it, two heavier lines, and a fine black thread still crimped from the strain and snap when it broke and he got away. Like medals with their ribbons frayed and wavering, a five-haired beard of wisdom trailing from his aching jaw. I stared and stared and victory filled up the little rented boat, from the pool of bilge where oil had spread a rainbow around the rusted engine to the bailer rusted orange, the sun-cracked thwarts, the oarlocks on their strings, the gunnels--until everything was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow! And I let the fish go. 6 Ronald Wallace Dogs When I was six years old I hit one with a baseball bat. An accident, of course, and broke his jaw. They put that dog to sleep, a euphemism even then I knew could not excuse me from the lasting wrath of memory’s flagellation. My remorse could dog me as it would, it wouldn’t keep me from the life sentence that I drew: For I’ve been barked at, bitten, nipped, knocked flat, slobbered over, humped, sprayed, beshat, by spaniel, terrier, retriever, bull and Dane. But through the years what’s given me most pain of all the dogs I’ve been the victim of are those whose slow eyes gazed at me, in love Robert Frost The Mending Wall Something there is that doesn't love a wall, That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it, And spills the upper boulders in the sun, And makes gaps even two can pass abreast. The work of hunters is another thing: I have come after them and made repair Where they have left not one stone on a stone, But they would have the rabbit out of hiding, To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean, No one has seen them made or heard them made, But at spring mending-time we find them there. I let my neighbor know beyond the hill; And on a day we meet to walk the line And set the wall between us once again. We keep the wall between us as we go. To each the boulders that have fallen to each. And some are loaves and some so nearly balls We have to use a spell to make them balance: 'Stay where you are until our backs are turned!' We wear our fingers rough with handling them. Oh, just another kind of out-door game, One on a side. It comes to little more: There where it is we do not need the wall: He is all pine and I am apple orchard. My apple trees will never get across And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him. He only says, 'Good fences make good neighbors'. Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder If I could put a notion in his head: 'Why do they make good neighbors? Isn't it Where there are cows? But here there are no cows. Before I built a wall I'd ask to know What I was walling in or walling out, And to whom I was like to give offence. Something there is that doesn't love a wall, That wants it down.' I could say 'Elves' to him, But it's not elves exactly, and I'd rather He said it for himself. I see him there Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed. He moves in darkness as it seems to me~ Not of woods only and the shade of trees. He will not go behind his father's saying, And he likes having thought of it so well He says again, "Good fences make good neighbors." 7 Part IV: Sound Anonymous Western Wind Western wind, when wilt thou blow, The small rain down can rain? Christ, if my love were in my arms, And I in my bed again! Marge Piercy The Secretary Chant My hips are a desk. From my ears hang chains of paper clips. Rubber bands form my hair. My breasts are wells of mimeograph ink. My feet bear casters. Buzz. Click. My head is a badly organized file. My head is a switchboard where crossed lines crackle. My head is a wastebasket of worn ideas. Press my fingers William Hathaway Oh, Oh My girl and I amble a country lane, moo cows chomping daisies, our own sweet saliva green with grass stems. “Look, look,” she says at the crossing, “the choo-choo's light is on.” And sure enough, right smack dab in the middle of maple dappled summer sunlight is the lit headlight – so funny. An arm waves to us from the black window. We wave gaily to the arm. “When I hear trains at night I dream of being president,” I say dreamily. “And me first lady,” she says loyally. So when the last boxcars, named after wonderful, faraway places, and the caboose chuckle by we look eagerly to the road ahead. And there, poised and growling, are fifty Hell's Angels and in my eyes appear credit and debit. Zing. Tinkle. My naval is a reject button. From my mouth issue canceled reams. Swollen, heavy, rectangular I am about to be delivered of a baby xerox machine. File me under W because I wonce was a woman. 8 Robert Francis Catch Two boys uncoached are tossing a poem together, Overhand, underhand, backhand, sleight of hand, every hand, Teasing with attitudes, latitudes, interludes, altitudes, High, make him fly off the ground for it, low, make him stoop, Make him scoop it up, make him as-almost-as possible miss it, Fast, let him sting from it, now, now fool him slowly, Anything, everything tricky, risky, nonchalant, Anything under the sun to outwit the prosy, Over the tree and the long sweet cadence down, Over his head, make him scramble to pick up the meaning, And now, like a posy, a pretty one plump in his hands. Lisa Parker Snapping Beans I snapped beans into the silver bowl that sat on the splintering slats of the porch swing between my grandma and me. I was home for the weekend, from school, from the North, Grandma hummed "What A Friend We Have In Jesus" as the sun rose, pushing its pink spikes through the slant of cornstalks, through the fly-eyed mesh of the screen. We didn't speak until the sun overcame the feathered tips of the cornfield and Grandma stopped humming, I could feel the soft gray of her stare against the side of my face when she asked, How's school a-going'? I wanted to tell her about my classes, the revelations by book and lecture, as real as any shout of faith and potent as a swig of strychnine. She reached the leather of her hand over the bowl and cupped my quivering chin; the slick smooth of her palm held my face the way she held tomatoes under the spigot, careful not to drop them, and I wanted to tell her about the nights I cried into the familiar heartsick panels of the quilt she made me, wishing myself home on the evening star. I wanted to tell her the evening star was a planet, that my friends wore noserings and wrote poetry About sex, about alcoholism, about Buddha. I wanted to tell her how my stomach burned acidic holes at the thought of speaking in class, speaking in an accent, speaking out of turn, how I was tearing, splitting myself apart with the slow-simmering guilt of being happy despite it all. I said, School's fine. We snapped beans into the silver bowl between us and when a hickory leaf, still summer green, skidded onto the porchfront, Grandma said, It's funny how things blow loose like that. Part V: Images Sheila Wingfield A Bird Unexplained In the salt meadow Lay the dead bird. The wind Was fluttering its wings 9 Margaret Atwood you fit into me you fit into me like a hook into an eye a fish hook an open eye Janice Townley Moore To a Wasp You must have chortled finding that tiny hole in the kitchen screen. Right into my cheese cake batter you dived. no chance to swim ashore, no saving spoon, the mixer whirring your legs, wings, stinger, churching you into such delicious death. Never mind the bright April day. Did you not see rising out of the cumulus clouds That fist aimed at both of us? Ernest Slyman Lightning Bugs In my backyard, They burn peepholes in the night And take snapshots of my house. Edwin John Pratt The Shark He seemed to know the harbour, So leisurely he swam; His fin, Like a piece of sheet-iron, Three-cornered, And with knife-edge, Stirred not a bubble As it moved With its base-line on the water. His body was tubular And tapered And smoke-blue, And as he passed the wharf He turned, And snapped at a flat-fish That was dead and floating. And I saw the flash of a white throat, And a double row of white teeth, And eyes of metallic grey, Hard and narrow and slit. Then out of the harbour, With that three-cornered fin Shearing without a bubble the water Lithely, Leisurely, He swam-That strange fish, Tubular, tapered, smoke-blue, Part vulture, part wolf, Part neither-- for his blood was cold. 1. Choose one of the above poems and analyze how the organization (stanzas, sentence length) attributes to the overall meaning of the poem. 2. Choose one of the poems above and analyze how the rhythm or rhyme contributes to the overall meaning of the poem.