Household Response to the 2008 Tax Rebates: Survey Evidence

advertisement

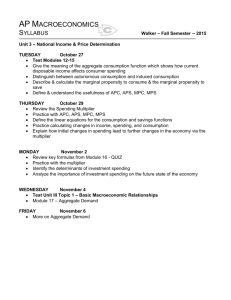

What is MPC from income shock? • Critical for getting the multiplier started • Vast literature on failure of LC/PIH prediction of response to temporary income – Euler equation: Hall, Campbell-Mankiw – Specific income shocks Specific income shocks Response to windfalls or anticipated income • Wilcox, Income tax refunds • Parker, Hitting the FICA ceiling • Stephens, Receipt of Social Security check • Souleles, Tuition payments – (Christian, labor supply response) • Hsieh, Alaska oil payments See literature review in Shapiro-Slemrod (2003) Survey Approach • • • • • Specific policy Estimate MPC, not GE effects Clearly endogenous Clearly income, not price/allocative What was household response to a specific policy at a specific time? Shapiro-Slemrod surveys 1992: 2001: 2008: 2009: 2011: Change in timing of withholding Rebate Rebate Making Work Pay credit (withholding) Social Security payroll tax holiday (withholding)—In field this spring Recent work joint with Claudia Sahm, FRB Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 • One-time stimulus payments, aka “Tax Rebates” • Typical rebate: – Singles $600 – Married $1200 – Plus $300 per child • Broad eligibility (did not need tax liability) • Phased out for upper income levels • Paid by EFT or check 2008 Stimulus Payments Large and distributed quickly • $96 billion – 0.8% of annual personal income – 8.7% of annual Federal personal tax receipts ≈ one-month of income tax revenue • Disbursed mainly in 2008:Q2 Questions surveys can answer • How much additional spending did the 2008 stimulus payments generate? • Timing of spending? • Types of spending and debt repayment? • Different responses across households? Research Design • Survey questions: Ask directly about response to rebates • Follow-up questions and multivariate analysis: Assess the survey responses • Validate survey responses: Compare to aggregate data on spending and debt • Compare to other surveys Key Survey Question Thinking about your family’s financial situation this year, did the tax rebate lead you mostly to increase spending, mostly to increase saving, or mostly to pay off debt? Response to 2008 Rebates Increase spending Increase saving Pay off debt Memo: Number of respondents Feb-Apr 20% 31% 49% 1,447 Survey Months May-Jun Nov-Dec 19% 22% 27% 23% 53% 55% 980 990 Pooled 20% 28% 52% 3,417 Note: Authors' weighted tabulation of the Reuters/Michigan Survey of Consumers. One-fifth of households mostly increased their spending Most common response is to pay off debt Distribution of responses stable across 2008, similar to responses to 2001 rebates Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) • “Mostly spend” rate not same as MPC – “Mostly spenders” do some saving – “Mostly savers” do some spending • Under a range of plausible distributional assumptions… 1/5 mostly spend MPC of 1/3 Age and Response to Rebates Age (years) Under 30 30-39 49-49 50-64 65 and over Under 65 65 and over Percent Spend 11% 17% 25% 21% 26% 20% 26% Oldest households have highest spending rate Qualitatively consistent with life-cycle consumption But spending rate high relative to pure life-cycle model Income and Response to Rebates Household Income $0 to $20,000 $20,001 to $35,000 $35,001 to $50,000 $50,001 to $75,000 More than $75,000 Refused / Don't know income Percent Spend 20% 22% 17% 17% 26% 30% Highest income households have highest spending rate Results robust to multivariate analysis Lower income households likely to pay off debt Income Expectations Multivariate Regression: Probability Mostly Spend Estimate Expected income growth g g > 4% 0 < g < 4% -10% < g < 0 g < -10% 3.9 (2.2) 1.7 (2.2) -0.8 (2.8) -5.1 (2.8) Expected income growth strongly is strongly associated with spending Summary of Age and Income Effects • Being young or poor does not indicate high spending rate – Debt repayment modal for less well off • Finding contrary to conventional wisdom – CBO, Hamilton Project (Jan 2008) white papers • Income growth a better indicator of liquidity-constrained behavior Type of Spending Specific Type of Spending Major household item (durables, appliances) Percent of Spenders 25% Other specific expenses 56% Food Gasoline, fuel Clothing Recreation (incl. travel) Housing-related expenses (incl. renovations) Vehicle-related (incl. purchases and repairs) Medical, education, other specific expenses General expenses Pay off credit card or other loan, pay taxes 10% 2% 8% 21% 9% 3% 2% 17% 3% Spending split between “regular expenses” and “something else” Household durables and recreation are most common types of spending Some question whether this spending is truly incremental Type of Debt Repayment Percent of Debt Repayers Credit card 51% Mortgage, home equity 9% Specific bills (medical, tuition) 26% Everyday bills (utilities, fuel), other debt 14% Most common response was paying down credit card balances Sizeable minority paid everyday bills—may indicate spending Using Survey Data for Aggregate Implications • Use survey data to estimate – MPC (implied by “mostly spend rate”) – Timing of spending • Use aggregate data – Level and timing of aggregate disbursements • Compare survey estimate to – Actual spending and saving – Debt levels • Direct effect only: No GE/multiplier effects Timing of Spending: Rebate Evidence When did spending increase? Within a few weeks Within 1-3 months More than 3 months Percent of Spenders 36% 50% 14% Spending occurred quickly—86 percent in first three months Low income and low asset spenders had faster response Disbursements of Rebates: Aggregate Data 60 48 Billions of Dollars (monthly rate) 50 40 28 30 20 14 10 4 2 0 April May June July Aug-Dec Personal Saving Rate Personal Saving Rate, Percent 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Jan-08 Apr-08 Actual Jul-08 Oct-08 Jan-09 Excludes Rebate Income and Rebate Spending Jump in the saving rate in spring 2008 mainly reflects boost to income Saving rate would have risen steadily without rebates Rebate’s Effect on Spending Growth: Survey-based Evidence Percent (annual rate) 3 2 1 0 2008Q1 2008Q2 2008Q3 -1 -2 Survey-based estimate of contribution of rebate 2008Q4 Spending Growth: Actual versus Excluding Rebate Effects 0 Percent (annual rate) 2008Q1 2008Q2 2008Q3 -1 -2 -3 -4 Actual Excluding rebate effects 2008Q4 Validating the survey evidence • Simulations of macro spending model • Comparisons with aggregate debt levels • Analysis of other surveys (see paper) All support our basic survey results Model Simulation Simple FRB consumption model: • Dynamic error correction model of consumption growth • Explanatory variables: – – – – Disposable income (excluding rebate) Net worth Federal Funds rate Consumer sentiment • Compare actual and simulated data Consumption Growth: Actual versus predicted Percent Change in Real PCE (a.r.) 2008Q1 2008Q2 2008Q3 2008Q4 Published national accounts data -0.6 0.1 -3.5 -3.1 Dynamic model simulation excluding rebate income 0.5 -2.2 0.5 -2.4 Difference between data and model simulation -1.1 2.2 -4.0 -0.7 Contribution of rebates to the change in real PCE estimated from responses in the Michigan survey 0.0 2.4 -0.3 -1.7 Did rebate reduce consumer debt in aggregate? Ratio of revolving credit to spending, in recessions Benefits of Survey Approach • Survey responses – Households’ counterfactual response • Standard data on behavior (aggregate or micro) – Hard to isolate policy effect from other shocks • Surveys give timely estimates of policies’ effects Implications for Fiscal Policy • Recent rebates have had modest spending rates • Low “bang for buck” • Large rebates nonetheless had noticeable temporary effect on spending Implications for Current Business Cycle • 2008 rebates – Raised spending growth in 2008Q2 – Lowered spending growth in 2008Q4 • Lesson for understanding 2008 – Consumption contraction began before fall crisis 2008 Rebate: CEX Evidence Consumer Expenditure Survey (Parker, Souleles, Johnson, and McClelland, 2011) • CEX questions about receipt of rebate • Related paper on 2001 rebate uses timing of receipt (randomized by Social Security number) as instrument • In 2008, little variation in timing so identification from cross-sectional variation 2008 Rebate: CEX Evidence • MPC on non-durables low • MPC on total consumption higher – Mainly coming from automobiles • Lagged/cumulative MPC larger Consumption response to the 2008 rebate Source: Parker, et al, 2011 Consumption response to the 2008 rebate, Cumulative Source: Parker, et al, 2011 Consumption response to the 2008 rebate, Durables Consumption response to the 2008 rebate Implications for Automobile Purchases in Aggregate 2008 JAN 2008 FEB 2008 MAR 2008 APR 2008 MAY 2008 JUN 2008 JUL 2008 AUG 2008 SEP 2008 OCT 2008 NOV 2008 DEC 2008 Total Real expenditures by households on motor vehicles, billion 2005 dollars, annual rate, seasonally adjusted 340.84 339.24 326.83 322.75 314.55 306.39 281.14 307.05 292.02 262.72 262.88 262.01 301.535 Payments from 2008 Rebates, nominal, annual rate 23.3 577.1 334.4 164.1 12.4 8.1 11.7 13.1 2.6 96 Nominal rebateinduced spending on Real rebate-induced Implied Share of new and used motor spending on new and Motor Vehicle vehicles implied by used motor vehicles Outlays Owing to Table 12 PSJM* implied by Table 12 PSJM Rebates 5.6 144.1 218.8 119.6 42.4 4.9 4.7 6.0 3.8 46 5.4 140.0 211.9 115.8 40.8 4.7 4.5 5.6 3.5 44 0.02 0.45 0.69 0.41 0.13 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.15 2008 Rebate: CEX and Survey Approach Cross-Validation • CEX includes Shapiro-Slemrod “mostly spend/save/pay debt” question • Somewhat more CEX respondents “mostly spend” – 1/5 in Michigan survey, 1/3 in CEX – Mostly pay off debt modal in both • CEX consumption strongly predicted by “mostly spend” Consumption response to 2008 rebate, Using survey question Source: Parker, et al, 2011 2008 Rebate: Summary • CEX and Michigan survey have similar estimates on impact • CEX has larger cumulative effect – mainly from automobiles – not precisely estimated • Cross-validation • Policymakers tend to focus on largest estimated MPC, which imply larger multipliers