Chapter 3 The International Monetary System

advertisement

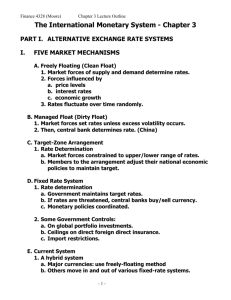

Chapter 3 The International Monetary System A. Exchange Rate Systems B. International Monetary System C. European Monetary System and Monetary Union D. Emerging Market Currency Crises 3.A Exchange Rate Systems Free (“clean”) float – Exchange rates are determined by currency supply and demand with no government intervention. – As economic parameters change, market participants adjust their current and expected future currency needs. – Shifts in currency needs in turn shift currency supply and demand schedules, as seen in Chapter 2. Managed (“dirty”) float – Central banks intervene to reduce economic volatility. – Three categories of intervention 1. Smoothing out daily fluctuations – central bank buys or sells currency to smooth exchange rate adjustments. 2. Leaning against the wind – measures taken to moderate or prevent short- or medium-term exchange rate fluctuations caused by random events. 3. Unofficial pegging – a country pegs the value of its currency to a foreign currency to protect the value of its exports. Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 1 3.A Exchange Rate Systems Target zone arrangement – Countries agree to adopt economic policies that maintain their exchange rates within a specific range. – Designed to minimize exchange rate volatility and enhance economic stability in participating countries. – Requires coordination of economic policy objectives and practices. Fixed-rate system – Governments maintain target exchange rates. – Central banks buy/sell currency to increase (“revalue”)/decrease (“devalue”) exchange rates when exchange rates threaten to deviate from their stated par values by more than an agreed-on percentage. – Monetary policy becomes subordinate to exchange rate policy. Hybrid system – current international system consisting of free-float, managed-float, and pegged currencies. Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 2 3.B International Monetary System (1) Gold Standard – participating countries fixed the prices of their currencies in terms of a specified amount of gold. Because the value of gold is fairly stable over time, the gold standard ensured long-run price stability for both individual countries and groups of countries, aka Self-balancing feature in Econ303 Classical Gold Standard (1821-1914) – Characterized by price-specie-flow mechanism • Changes in the price level in one country were offset by an automatic balance of payments (“BOP”) adjustment. – As U.S. exchange rate falls, exports rise, causing BOP surplus and inflow of foreign gold. – U.S. prices rise, foreign prices fall – U.S. exports fall, foreign exports rise – BOP equilibrium achieved Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 3 3.B International Monetary System (3) Gold Exchange Standard (1925-1931) – The U.S. and England could hold only gold reserves – Other nations could hold both gold and dollars/pounds as reserves. – In 1931, England departed from gold given massive gold and capital flows stemming from an unrealistic exchange rate, ending the Gold Exchange Standard. 1931-1944 – Beggar thy neighbor devaluations – countries devalued their currencies to maintain trade competitiveness, leading to a trade war. Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 4 3.B International Monetary System (4) Bretton Woods System (1946-1971) – Bretton Woods Conference, 1944 • New postwar monetary system – Allied nations pledged to maintain a fixed (pegged) exchange rate in terms of the dollar or gold. – 1 ounce of gold = $35 – Exchange rates could fluctuate only within 1% of their stated par values. – Fixed rates were maintained by central bank intervention in foreign exchange markets. Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 5 3.B International Monetary System (5) Bretton Woods System (1946-1971), continued – Bretton Woods Conference, 1944, continued • Two new institutions created – International Monetary Fund (IMF) – created to promote monetary stability • Role has evolved over time • Oversees exchange rate policies in 182 member countries • Advises developing countries on economic policy • Lender of last resort • Moral hazard – expectation of IMF bailouts leads investors to underestimate risks of lending to governments that pursue irresponsible policies – International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank) – created to lend money to countries to rebuild their war-damaged infrastructures Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 6 3.B International Monetary System (6) Bretton Woods System (1946-1971), continued – Collapse of Bretton Woods system • Inflation in the U.S. stemming from the Johnson Administration printing money instead of raising taxes to finance Viet Nam conflict. • West Germany, Japan, and Switzerland would not accept the inflation that a fixed exchange rate with the dollar would have imposed on them. Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 7 3.B International Monetary System (7) Post-Bretton Woods System (1971-Present) – Smithsonian Agreement • Dollar was devalued to 1/38 of an ounce of gold. • Other currencies revalued by agreed-on amounts in terms of the dollar. – Attempts to set new fixed rates unsuccessful. – International floating exchange rate system instituted in 1973. • System supposed to reduce economic volatility and facilitate free trade. – Floating rates would offset international differences in inflation. – Real exchange rates would stabilize given gradual changes in underlying conditions affecting trade and productivity of capital. – Nominal exchange rates would stabilize if countries coordinated their monetary policies to achieve inflation rate convergence. • However, currency volatility has increased due to non-monetary global economic shocks (e.g., changing oil prices). Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 8 3.C European Monetary System (1) European Monetary System (EMS) – Began operating in March 1979. – Purpose: Foster monetary stability in the European Community (EC) – Members established the European Currency Unit (ECU), a composite currency consisting of fixed amounts of the 12 EC member currencies. – The quantity of each currency reflected each country’s relative economic strength within the ECU. – In 1992, the EC became the European Union (EU). – The EU currently has 27 member states. Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 9 3.C European Monetary System (3) European Monetary Union (EMU, or EU) – Maastricht Treaty • Formalized the EC’s moved toward a monetary union • EC nations would establish the European Central Bank with sole power to issue a single currency (euro). – On January 1, 1999, the euro became a currency and conversion rates for the euro were locked in for member countries. – On January 1, 2002, member countries’ currencies were replaced by euro bills and coins. – To join the EU, countries were subjected to the Maastricht criteria • Government debt ≤ 60% of GDP • Budget deficit ≤ 3% of GDP • Inflation ≤ 1.5 percentage points above the average rate of Europe’s three lowest-inflation countries • Long-term interest rates ≤ 2 percentage points above the average interest rate in the three lowest-inflation countries Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 10 3.C European Monetary System (4) European Monetary Union (EMU, or EU), continued – Consequences of EU • Lower cross-border currency conversion costs • Eliminated risk of currency fluctuations • Facilitated cross-border price comparisons • Encouraged flow of trade and investments among member countries • Greater integration of Europe’s capital, labor, and commodity markets • Increased Europe’s competitiveness • Greater coordination of monetary policy Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 11 3.D Emerging Market Currency Crises (1) Currency crises spread from one country to another by two means. – Trade links – e.g., when Argentina is in crisis, it imports less from Brazil, causing Brazil’s economy to contract and its currency to weaken. Brazil’s contraction will in turn affect other trade partners. – The financial system – distress in one emerging market causes investors to exit other countries with similar risk profiles. Common denominator in promoting currency crises: Countries issue too much short-term debt closely linked to the dollar. When the dollar depreciates, the cost of repaying dollar-linked bonds soars. Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 12 3.D Emerging Market Currency Crises (2) Circumventing emerging market crises – Currency controls • Abandoning free capital movement to insulate a country’s currency from speculative attacks, e.g. China • However: – Open capital markets channel savings to where they are most productive; – Developing nations need foreign capital and know-how; and – Currency controls have led to corruption. – Freely floating currency – floating rates absorb the pressures created in emerging countries that simultaneously peg their exchange rates and pursue independent monetary policy. – Permanently fix the exchange rate – through dollarization, use of a currency board, or a monetary union, an economy can permanently fix its exchange rate, e.g. Hong Kong Chapter 3: The International Monetary System 13