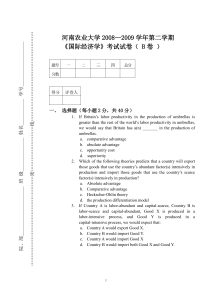

Part 3

advertisement

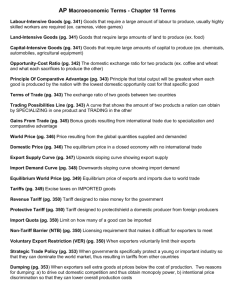

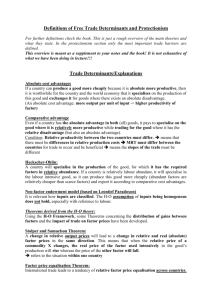

International Trade Appleyard / Field / Cobb Sixth Edition Brief Contents • Chapter 1 The world of International Economics • PART 1 THE CLASSICAL THEORY OF TRADE • Chapter 2 Early Trade Theories: Mercantilism and the Transition to the Classical World of David Ricardo • Chapter 3 The Classical World of David Ricardo and Comparative Advantage • Chapter 4 Extensions and Tests of the Classical Model of Trade • PART 2 NEOCLASSICAL TRADE THEORY • Chapter 5 Introduction to Neoclassical Trade Theory: Tools to Be Employed • Chapter 6 Gains from Trade in Neoclassical Theory • Chapter 7 Offer Curves and the Terms of Trade • Chapter 8 The Basis for Trade: Factor Endowments and the HeckscherOhlin Model • Chapter 9 Empirical Tests of the Factor Endowments Approach • PART 3 ADDITIONAL THEORIES AND EXTENSIONS • Chapter 10 Post-Heckscher-Olin Theories of Trade and Intra-Industry Trade • Chapter 11 Economic Growth and International Trade • Chapter 12 International Factor Movements • PART 4 TRADE POLICY • Chapter 13 The Instruments of Trade Policy • Chapter 14 The Impact of Trade Policies • Chapter 15 Arguments for Interventionist Trade Policies • Chapter 16 Political Economy and U.S. Trade Policy • Chapter 17 Economic Integration • Chapter 18 International Trade and the Developing Countries The World of International Economics Chapter 1 Introduction • Welcome to the study of international trade! You will be studying one of the oldest branches of economics. The study of international economics concerns decision making with respect to the use of scarce resources to meet desired economics objectives. The Nature of Merchandise Trade • Throughout the past four decades, international trade volume has, on average, outgrown production. 1. The Geographical composition of Trade; The industrialized countries dominate world trade. 2. The Commodity Composition of Trade; Among the 2005 commodity composition of world trade, manufactures account for 72% percent of trade, with the remaining amount consisting of primary prodects. • 3.U.S. International Trade Canada is the most important trading partner, both in exports and imports; Agricultural products are an important source of exports; The capital goods category is the largest single export category; Industrial supplies is also an important export category. World Trade In Services • In 2005, the trade in services estimated to be more than $2 trillion. International trade in services broadly consists of commercial services, investment income, and government services. International services trade is also concentrated among the industrial countries. The Changing Degree of Economic Interdependence • It is important to recognize both the large absolute level of international trade and the relative importance of trade has been growing for nearly every country and for all countries as a group. Early Trade Theories: Mercantilism and the Transition to the Classical World of David Ricardo Chapter 2 Introduction • The Oracle in the 21st Century Diligence and intelligence are strategies for improving one’s lot in life. Do what you do best. Trade for the rest. It has long been perceived that nations benefit in some way by trading with other nations. Mercantilism Mercantilism refers to the collection of economic thought that came into existence in Europe during the period from 1500 to 1700. Mercantilism is often referred to as the political economy of state building. • 1.The Mercantilist Economic System Central to Mercantilist thinking was the view that national wealth was reflected in a country’s holdings of precious metals. Economic activity is viewed as a zerosum game in which one country’s economics gain was at the expense of another. • 2.The Role of Government Controlling the use and exchange of precious metals. Maximizing the likelihood of a positive trade balance and the inflow of specie. • 3.Mercantilism and Domestic Economic Policy. Controlling of industry and labor. Pursuing the policies that kept wages low. The Challenge to Mercantilism by Early Classical Writers • 1. David Hume-The Price-Specie- Flow Mechanism A nation could continue to accumulate specie without any repercussions to its international competitive position. The accumulation of gold by means f a trade surplus would lead to an increase in the money supply and therefore to an increase in prices and wages. The increase would reduce the competitiveness of the country. • 2. Adam Smith and the Invisible Hand Laissez faire: Allowing individuals to pursue their own activities within the bounds of law and order and respect for property rights. Countries should specialize in and export those commodities in which they had an absolute advantage and should import those commodities in which the trading partner had an absolute advantage. Learning Objectives • To learn the basic concepts and policies associated with Mercantilism; • To understand Hume’s pricespecie-flow mechanism and the challenge it posed to Mercantilism; • To grasp Adam Smith’s concept of wealth and absolute advantage as foundations for international trade. The Classical World of David Ricardo and Comparative Advantage Chapter 3 Introduction • Some Common Myths We hear that trade makes us poorer. We hear that exporters are good because they support a country’s industry, but imports are bad because they steal business from domestic producers. The underlying basis for these words is comparative advantage. • Assumptions of the Basic Ricardian Model There are 11 assumptions. • Ricardian Comparative Advantage Ricardo presented a case describing the production of two commodities, wine and cloth, in England and Purtugal. Comparative Advantage and the Total Gains From Trade The essence of Ricardo’s argument is that international trade does not require different absolute advantage and that it is possible and desirable to trade when comparative advantage exist. • 1. Resource Constraints To demonstrate the total gains from trade between these two countries, it is necessary to first establish the amount of the constraining resource-laboravailable to each country. Suppose that country A has 9,000 labor hours available and country B has 16,000 labor hours available. Examining the equivalent quantity of domestic labor services consumed before and after trade for each country. After trade, country A consumes 3,500C and 2,000W. Country A has gained the equivalent of 500 labor hours. After trade, country B consumes 5,500C and 1,500W. Country B has gained the equivalent of 1,000 labor hours. • 2. Complete Specialization Complete Specialization: All resources are devoted to the production of one good, with no production of the other good. Country A producing only cloth and country B producing only wine, they exchange 2,000 barrels of wine for 5,000 yards of cloth. A would gain 10,000 hours, which is greater than the labor value of consumption in either autarky or in the case of trade with no production change. Country B is also better off because it now consumes 5,000 yards of cloth and 2,000 barrels of wine with a labor value of 18,000 hours. Representing the Ricardian Model with Production-Possibilities Frontiers The PPF reflects all combinations of two products that a country can produce at a given point in time given its resource base, level of technology, full utilization of resources, and economically efficient production. • 1. Production Possibilities-An Example The figures on labor hours and production for country A and B make it possible to display the productionpossibilities frontiers for each country. With the initiation of trade, country A was able to produce a new, flatter consumption-possibilities frontier with trade. Country A can now choose to consume a combination of goods that clearly lies outside its own PPF in autarky, thus demonstrating the potential gains from trade. The situation is similar for country B. • Maximum Gains from Trade In the Classical model, production generally takes place at an end point of the PPF of each country. Our procedure showed that trade could benefit a country even if all of its resources were “frozen” into their existing production patterns. There is no reason to stop for producers at any point on the PPF until the maximum amount of production is reached. • Comparative advantage-some concluding observations Up to this point, nothing has been said about the basis for the comparative advantages tat a country might have in trade. The Classical economists thought that participation in foreign trade could be a strong positive force for development. Specialization in the production of goods that have few links to the rest of the economy can lead to a lopsided pattern of growth. The Classical writers have made us aware that trade not only produces static gains but also can be a positive vehicle for economic growth and development and that it should be encouraged. Learning Objectives • To understand comparative advantage as • • • a basis for trade between countries; To identify the difference between comparative advantage and absolute advantage; To quantify the gains from trade in a two-country, two-good model; To recognize comparative advantage and the potential gains from trade using production-possibilities frontiers. Extensions and Tests of the Classical Model of Trade Chapter 4 Introduction • Trade Complexities in the Real World In light of ongoing structural changes taking place in the increasingly integrated trading world and changes in demand for certain kinds of labor, international competitiveness of certain key regional industries has taken center stage in the current political arena, and the effect of reduced trade barriers is often cited as the cause of these industry problems. The Classical Model in Money Terms The first extension of the Classical model changes the example from one of labor requirements per commodity to a monetary value of the commodity. One the exchange rate is established, the value of all goods an be stated in term of one currency. Assume that the fixed exchange rate is 1 escudo(esc)=£1. The pattern of trade now responds to money-price differences. The result of trade is the same as that reached in the examination of relative labor efficiency between the two countries. • Wage Rate Limits and Exchange Rate Limits Wage rate limits: The endpoints of the range within which the wage can vary without eliminating the basis for trade. Similarly, there are exchange rate limits. The export condition indicates when a country has a cost advantage in a particular product, that condition can be used to determine the wage that will cause prices to be the same in the two countries. Multiple Commodities • 1. The Effect of Wage Rate Changes Expanding the number of commodities is a useful extension of the basic Classical model because it permits an analysis of the effects of exogenous changes in relative wages or the exchange rate on the pattern of trade. 2. The Effect of Exchange Rate Changes Changes in the exchange rate also alter a country’s trade pattern. A shift in tastes and preferences toward foreign goods, which leads to an increase in the domestic price of foreign currency, will make domestic products cheaper when measured in that foreign currency, thereby increasing the competitiveness of a country in terms of exports. The equilibrium terms of trade will reflect the size and elasticity of demand of each country for each other’s products, given the initial production conditions determined by the resource endowments and technology. • Transportation Costs The incorporation of transport costs alters the results covered to this point, because the cost of moving a product from one country’s location to another affects relative prices. • Multiple Countries When several countries are taken into account, the specification of the trade pattern is less straightforward. • Evaluating the Classical Model Although the Classical model seems limited in today’s complex production world, economists have been interested in the extent to which its general conclusions are realized in international trade Learning Objectives • To grasp how wages, productivity, and exchange rates affect comparative advantage and international trade patterns; • To understand the implications of extending the basic model of comparative advantage to more than two countries and/or commodities; • To make the reader aware that real-world trade patterns are consistent with underlying comparative advantage. Introduction to Neoclassical Trade Theory: Tools to Be Employed Chapter 5 Introduction This chapter presents basic microeconomics concepts and relationships employed in analyzing trade patterns and the gains from trade. The Theory of Consumer Behavior • 1. Consumer Indifference Curves Traditional microeconomic theory begins the analysis of individual consumer decisions through the use of the consumer indifference curve. Cardinal utility and ordinal utility. Transitivity means that if a bundle of goods B is preferred (or equal) to a bundle of goods A and if a bundle of goods C is preferred (or equal) to a bundle of goods B, then bundle C must be preferred (or equal) to bundle A. An indifference curve must be downward sloping because less of one good must be compensated with more of the other good to maintain the same satisfaction level. Diminishing marginal rate of substitution. An indifference curve can not intersect for the individual consumer. • 2. The Budget Constraint; To determine actual consumption on the individual consumer’s indifference curve, we need to examine the income level of the consumer. The income level is represented by the budget constraint or budget line. • 3. Consumer Equilibrium The objective of the consumer is to maximize satisfaction, subject to the income constraint. The individual indifference curves show levels of satisfaction, and the budget line indicates the income constraint, the consumer maximizes satisfaction when the budget line just touches the highest indifference curve attainable. Production Theory • 1. Isoquants An isoquant is the concept that relates output to the factor inputs. An isoquant shows the various combinations of the two inputs that produces the same level of output. The exact shape of an isoquant reflects the subsitution possibilities between capital and labor in the production process. A major feature of isoquants is that tey have cardinal properties rather than simply ordinal properties. The negative of the slope of the isoquant at any point is equal to the ratio of the marginal productivities of the factors of production. The ratio of marginal productivities is often referred to as the marginal rate of technical substitution. • 2. Isocost Lines An isocost line shows the various combinations of the factors of production that can be purchased by the firm for a given total cost at given input prices. The negative of the slope of a isocost is equal to the ratio of the wage rate to the rental rate on capital. • 3. Producer Equilibrium. The choice of the combination of factors of production to employ involves consideration of factor prices and technical factor requirement. At the equilibrium point the isoquant is tangent to the isocost, and the firm is obtaining the maximum output for the given cost. The Edgeworth Box Diagram and the Production-Possibilities Frontier • 1. The Edgeworth Box Diagram Construction of a typical Edageworth box diagram begins by considering firms in two separate industries, industry X and industry Y. Draw the isoquants for firms in industry X, and draw the isoquants for firms in industry Y. The relative factor prices (w/r)1 facing the two industries will be identical. The Edgworth box diagram takes the isoquants of these two industries and puts them into one diagram. Production efficiency locus. • 2. The Production-Possibilities Frontier Unlike the PPF used by the Classical economists, this PPF demonstrates increasing opportunity cost. With increasing opportunity costs, the shape of the PPF is thus concave to the origin or bowed out. Marginal rate of transformation, which reflects the change in Y (ΔY) associated with a change in X (ΔX). The negative slope or –(ΔY/ ΔX) is a positive number. Learning Objectives • To review the microeconomic principles of consumer and producer behavior; • To understand the concept and limitations of a community indifference curve; • To recognize the underlying basis for a production-possibilities frontier with increasing opportunity costs. Gains from Trade in Neoclassical Theory Chapter 6 Introduction In this chapter we use the microeconomics tools developed in Chapter 5 to present the basic case for participating in trade and thus for avoiding these welfare costs of trade restrictions. This case includes increasing opportunity costs, factors of production besides labor, and explicit demand considerations. Autarky Equilibrium Autarky means total absence of participation in international trade. The economy is assumed to be seeking to maximize its well-being through the behavior of its economic agents. In autarky, as in trade, production takes place on the PPF. The equilibrium is at the point where the PPF is tangent to the price line for the two goods. Introduction of International Trade Suppose international trade opportunities are introduced into theis autarkic situation. Trade Triangle. • 1. The Consumption and Production Gains from Trade Economists sometimes divide the total gains from trade into two conceptually distinct parts: the consumption gain and the production gain. The consumption gain from trade refers to the fact that the exposure to new relative prices, even without changes in production, enhances the welfare of the country. Moving production toward the comparative-advantage good thus increases welfare. • • 2. Trade in the Partner Country. Because of the relative prices available through international trade, producers in the partner country have an incentive to produce more of good Y and less of the X good since partner country has a comparative advantage in good Y. With trade, the partner country’s consumers are able to reach a higher indifference curve. Minimum Conditions for Trade • 1. Trade Between Countries with Identical PPFs According to the neoclassical theory, two countries with identical production conditions can benefit from trade. Different demand conditions in the two countries and the presence of increasing opportunity costs are the two principal conditions. 2. Trade Between Countries with Identical Demand Condition Production conditions may differ because different technologies are employed in two countries with the same relative amounts of the two factors, capital and labor. Country I, which is more efficient in producing good X, will find itself producing and consuming more of this product in autarky. Similarly, country II produces more good Y. Country I will export good X and import good Y at terms of trade that are between the two autarky price ratios, and it will increases production of good X and decrease production of good Y. Each country can then attain a higher indifference curve. Some Important Assumptions in the Analysis This section briefly discusses three important assumptions used in the previous analysis that may need to be taken into account when examining the “real world”. • 1. Costless Factor Mobility One important assumption is that factors of production can shift readily and without cost along the PPF as relative prices change and trade opportunities present themselves. • 2. Full Employment of Factors of Production This assumption is related to the problem of adjustment. All of a country’s factors of production are fully employed. The country is operating on the PPF. • 3. The Indifference Curve Map Can Show Welfare Changes If intersections of community indifference curves occur, there might be a problem in interpreting welfare changes when a country moves from autarky to trade. We cannot be sure that the direction of the actual welfare can be meaningfully ascertained. Learning Objectives • To understand economic equilibrium in a • • • country that has no trade; To grasp the welfare-enhancing impact of opening a country to international trade; To realize that either supply differences or demand differences between countries are sufficient to generate a basis for trade To appreciate the implications of key assumptions in the neoclassical trade model. Offer Curves and the Terms of Trade Chapter 7 Introduction • Terms-of-Trade Shocks This chapter introduces and explains the factors that determined the terms of trade or posttrade prices. An important simplification was made: World prices with trade were assumed to be at a certain level. An important analytical concept employed to explain the determination of the terms of trade is known as the offer curve. A Country’s Offer Curve The offer curve or reciprocal demand curve of a country indicates the quantity of imports and exports the country is willing to buy and sell on world markets at all possible relative prices. The offer curve is a combination of a demand curve and a supply curve. The most useful feature of the offer curve diagram is that it can bring two trading countries together in one diagram. Trading Equilibrium With the two countries’ offer curves brought together in one figure, we can indicate the trading equilibrium and show the equilibrium terms of trade. The equilibrium point E occurs at the intersection of the two offer curves. At point E, the quantity of exports that country I wishes to sell exactly equals the quantity of imports that country II wishes to buy. Similar to country I. Shifts of Offer Curves The shift is analogous to an “increase in demand” in the ordinary demandsupply diagram. An increased willingness to trade in the offer curve analysis means that, at each possible terms of trade, the country is willing to supply more exports and demand more imports. Similarly, a decrease in willingness to trade or a decrease in reciprocal demand is indicated by a shifted offer curve which pivoted inward to the left. Elasticity and the Offer Curve The shape can be discussed in terms of the general concept of elasticity. Five types of offer curve based on different elasticity of demand. • Other Concepts of the Terms of Trade Income terms of trade: The commodity terms of trade multiplied by a quantity index of export. Single Factoral Terms of Trade: The commodity terms of trade multiplied by an index of productivity in the export industries. • Double factoral terms of trade Double factoral terms of trade ratio is the single factoral terms of trade divided by the index of productivity in the export industries of the trading partners. Learning Objectives • To understand a country’s offer curve • • • and how it is obtained; To learn how the equilibrium international terms of trade are attained; To identify and determine how changes in both supply and demand conditions influence a country’s international terms of trade and volume of trade To appreciate the usefulness of different concepts of the terms of trade. The Basis for Trade: Factor Endowments and the Heckscher-Ohlin Model Chapter 8 Introduction • Do Labor Standards Affect Comparative Advantage? This chapter will examine in greater detail the factors that influence relative prices prior to the international trade, focusing on differences in supply and/or demand conditions in the two countries. Supply, Demand, and Autarky Prices The source of differences in pretrade price ratios between countries lies in the interaction of aggregate supply and demand as represented by their respective production-possibilities frontiers and community indifference curves. Differences in either demand or supply conditions are sufficient to provide a basis for trade between two counties. Factor Endowments and the Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem • 1. Factor Abundance and Heckscher-Ohlin Different factor endowments refers to different relative factor endowments, not different absolute amounts. Relative factor abundance may be defined in two ways: the physical definition and the price definition. The physical definition explains factor abundance in terms of the physical units of two factors. The price definition relies on the relative prices of capital and labor to determine the type of factor abundance characterizing the two countries. One definition focuses on physical availability, and the other focuses on factor price. • Commodity Factor Intensity and Heckscher-Ohlin A commodity is said to be factor-xintensive whenever the ratio of factor x to a second factor y is larger when compared with a similar ratio of factor usage of a second commodity. • The Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem The set of assumptions about production leads to the conclusion that the production possibilities frontier will differ between two countries solely as a result of their differing factor endowments. Combine these two differently shaped PPF with the same set of tastes and preferences, two different sets of relative prices will emerge in autarky. The international terms of trade must lie necessarily between the two internal price ratios. Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem: A country will export the commodity that uses relatively intensively abundant factor of production, and it will import the good that uses relatively intensively its relatively scarce factor of production. • The Factor Price Equalization Theorem As trade takes place between two countries, prices adjust until both countries face the same set of relative prices. Factor Price Equalization Theorem: In equilibrium, with both countries facing the same relative (and absolute) product prices, with both having the same technology, and with constant returns to scale, relative (and absolute) costs will be equalized. The only way this can happen is if, in fact, factor prices are equalized. • The Stolper-Samuelson Theorem and Income Distribution Effects of Trade in the Hechscher-Ohlin Model With full employment both before and after trade takes place, the increase in the price of the abundant factor and the fall in the price of the scarce factor because of trade imply that the owners of the abundant factor will find their real incomes rising and the owners of the scarce factor will find their real incomes falling. Theoretical Qualifications To Heckscher-Ohlin • Demand Reversal; • Factor-Intensity Reversal; • Transportation Costs; • Imperfect Competition; • Immobile or Commodity-Specific Factors; • Other Considerations. Learning Objectives • To understand how relative factor • • • endowments affect relative factor prices; To recognize how different relative factor prices generate a basis for trade; To learn how trade affects relative factor prices and income distribution; To understand how real-world phenomena can modify Heckscher-Ohlin conclusions. Empirical Tests of the Factor Endowments Approach Chapter 9 Introduction • Theories, Assumptions, and the Role of Empirical Work This chapter will follow the second approach by examining the empirical tests of Heckscher-Ohlin predictions in an attempt to find which of the often strict assumptions are crucial. • The Leontief Paradox In 1953, Leontief made use of his own invention-an input-output table-to test the H-O prediction. Leontief found that the most important export industries tended to have lower K/L ratios and higher labor requirements and lower capital requirements per dollar of output than did the most important import competing industries. Suggested Explanations for the Leontief Paradox • 1. Demand Reversal In demand reversal, demand patterns across trading partners differ to such an extant that trade does not follow the H-O pattern when the physical definition of relative factor abundance is used. The validity of demand reversal as an explanation of the Leontief paradox is an empirical question. • Factor-Intensity Reversal Factor-intensity reversal(FIR) occurs when a good is produced in one country by relatively capital-intensive methods but is produced in another country by relatively labor-intensive methods. • U.S. Tariff Structure This explanation for the Leontief paradox focuses on the factor intensity of the goods that primarily receive tariff (and other trade barrier) protection in the United States. In the United States, labor will be more protectionist than will owners of capital. Therefore, U.S. trade barriers tend to hit hardest the imports of relatively labor-intensive goods. The composition of the U.S. import bundle is relatively more capital intensive . • Different Skill Levels of Labor In this explanation of the Leontief paradox, the basic point is that the use of “labor” as a factor of production may involve a category that is too aggregative, because there are many different kinds and qualities of labor. Donald Keesing (1966) found that U.S. exports embodied a higher proportion of category I workers (scientists and engineers) and largest fraction of category VIII workers (unskilled and semiskilled workers). • The Role of Natural Resources This explanation also builds around the notion that a two-factor test is too restrictive for proper assessment of the empirical validity of the H-O Theorem. In the context of the Leontief paradox, many of the import-competing goods labeled as “capital intensive” were really “natural resource intensive”. Other Tests of the HeckscherOhlin Theorem • Factor Content Approach with Many Factors • Comparisons of Calculated and Actual Abundances; • Productivity Differences and “Home Bias”. • Heckscher-Ohlin and Income Inequality Learning Objectives • To learn about the failure of U.S. trade patterns to conform to Heckscher-Ohlin predictions; • To understand possible explanations for the U.S. trade paradox; • To become acquainted with issues arising from Heckscher-Ohlin tests; • To grasp the role of trade in generating growing income inequality in developed countries. Part 3 Additional Theories And Extensions Post-Heckscher-Ohlin theories of trade and intra-industry trade Chapter 10 Learning objectives 1 Explanations for the basis of trade in manufactures beyond Heckscher-Ohlin 2 The roles of technology dissemination, demand patterns, and time in affecting trade 3 How the presence of imperfect competition can affect trade 4 Intra-industry trade phenomenon Post-Heckscher-Ohlin theories of trade The imitation lag hypothesis Two adjustment lags: • The imitation lag: the length of time that elapses between the product’s introduction in country Ⅰ and the appearance of the version produced by firms in country Ⅱ. • The demand lag: the length of time between the product’s appearance in country Ⅰ and its acceptance by consumers in country Ⅱ as a good substitute for the products they are currently consuming. • The product cycle theory • Builds on the imitation lag hypothesis • A typical “new product”: 1)it will cater to high-income demands 2)it promises, in its production process, to be labor-saving and capital-using in nature • Three stages in life cycle • New product stage • Maturing-product stage • Standardized-product stage • The Linder theory • Premises: • Goods A,B,C,D,E,F and G are arrayed in ascending order of product “quality” or sophistication. • Country Ⅰ has a per capita income level that yields demands for goods A,B,C,D and E. • Country Ⅱ has a slightly higher per capita income level therefore it may demand and produce goods C,D,E,F and G. • Analyze: • Trade will occur in goods that have overlapping demand • Goods C,D,E will be trade between Country Ⅰ and Country Ⅱ • Conclusion: • International trade in manufactured goods will be more intense between countries with similar per capita income levels than between countries with dissimilar per capita income levels • Economies of scale • In a two-country world where the countries have identical PPFs and demand conditions, economies of scale is the new reason for trade. • The Krugman Model • Premises: • This model rests on economies of scale and monopolistic competition. • Labor is the only factor of production. • The scale economies: L=a+bQ • Monopolistic competition: • many firms in the industry and easy entry and exit. • zero profit for each firm in the long run. • product differentiation. FIGURE Basic Krugman Diagram P/W z P z’ E (P/W)1 z E’ (P/W)2 z’ P c2 c1 Per capita consumption, c • More premises: • Country Ⅰ and country Ⅱ • Same tastes, technology, and characteristics of the factors of production • Identical in size (not necessary) • When the two are opened to trade: • Market size is enlarged; • economies of scale came come into play • production costs can be reduced • All consumer’s well-being is increased • Other Post-Heckscher-Ohlin theories • The reciprocal dumping model • The gravity model Intra-industry trade (IIT) • Intra-industry trade: • A country both export and import items in the same product classification category. • inter-industry trade: • A country’s exports and imports are in different product classification category. • Reasons for intra-industry trade • • • • • • Product differentiation Transport costs Dynamic economies of scale Degree of product aggregation Differing income distributions in countries Differing factor endowments and product variety The level of a country’s IIT Greater per capita income Greater national income Greater openness Existence of a common border with principal trading partners Less distance from trading partners Greater amount of Intra-industry trade Economic growth and international trade Chapter 11 Learning objectives 1 The different ways growth can affect trade 2 How the source of growth affects the nature of production and trade 3 How growth and trade affect welfare in the small country 4 How growth in a large country can have different welfare effects than growth in a small country Classifying the trade effects of economic growth • Trade effects of production growth • Premises : • Small country (France) • Increasing opportunity costs • Currently in equilibrium at a given set of international prices FIGURE 1 production effects of growth Electronics Electronics Ⅳ Ⅲ B Ⅰ A Imports A Exports Wine (a) France (b) France Ⅱ Wine • Points beyond point A that fall on the line: a neutral production effect • Region Ⅰ: protrade production effect • Region Ⅱ: ultra-protrade production effect • Region Ⅲ: antitrade production effect • Region Ⅳ: ultra-antitrade production effect • Trade effects of consumption growth • Points lying beyond B on the straight line passing through point B and the origin of the original axes: neutral consumption effect • Region Ⅰ: antitrade consumption effect • Region Ⅱ: ultra-antitrade consumption effect • Region Ⅲ: protrade consumption effect • Region Ⅳ: ultra-protrade consumption effect FIGURE 2 consumption effects of growth Ⅲ Ⅳ Electronics Ⅰ B Ⅱ Wine (b) France Sources of growth and the productionpossibilities frontier • The effects of technological change • Assume: two inputs (capital and labor) • New types of technology: factor neutral; labor saving; capital saving Autos Autos Commodity-specific technological change Food Commodity-neutral technological change Food Figure 3 the effects of technological change on the PPF • The effects of factor growth FIGURE 4 effects of factor growth on the PPF Cutlery (K-intensive) Factor-neutral growth Cheese (L-intensive) (a) Growth in capital only (b) Growth in labor only (c) Factor growth, trade, and welfare in the small-country case • Premises: • A small country that cannot influence world prices, which remain constant • Two factors: labor, capital • One factor grows and the other remain fixed • Analyze: • What effect does factor growth have on trade in the small-country case? • Conclusion: • Growth in one factor leads to an absolute expansion in the product that uses that factor intensively and an absolute contraction in output of the product that uses the other factor intensively— Rybczynski theorem Growth, trade, and welfare: the largecountry case • Premises: • A large that can influence international prices • Growth of the abundant factor causes an ultra-protrade production effect • Neutral consumption effect • Growth can result in declining wellbeing in two ways: • Welfare declined by the deterioration in the international terms of trade • Even if capital is the growing abundant factor and the negative terms-of-trade effects are sufficiently strong, the country could be worse off after growth International Factor Movements Chapter 12 Learning objectives • The different types of foreign investment and the welfare effects of capital movements • The determinants of foreign direct investment and the associated costs and benefits • The motivation for labor migration and its effects on participating countries • The size and importance of international remittances International capital movements through FDI and multinational corporations • Foreign investors in China: “good” or “bad” • from the Chinese perspective Good: • Higher wages for worker • Tariff revenue collection for state • Bad: • Higher wager wage premium for state firms • Tariff revenue collection is bad for state firms • High tariff rate is bad for consumer welfare • Definitions • Foreign direct investment (FDI) • Foreign portfolio investment (FPI) • MNC/MNE/TNC/TNE • Reasons for international movement of capital • Firms will invest abroad in response to large and rapidly growing markets for their products • Developed-country firms will invest overseas if the recipient country has a high per capita income • Foreign firm can secure access to mineral or raw material deposits • Tariffs and nontariff barriers in the host country also can induce an inflow of FDI • Low relative wages in the host country • Firms also need to invest abroad for defensive purposes to protect market share • Invest abroad as a means of risk diversification • Some firm-specific knowledge or assets that enable the foreign firm to outperform the host country’s domestic firms • Analytical effects of international capital movements • Assume: • Only two countries in the world • Two factors of production—capital and labor • Homogeneous good • Analyze : MPPK1 MPPK2 MPPK2 MPPK1 C r1 r2 E r1’ r2’ r1’ B’ B K1 K 2 Capital • Conclusion • Total output rises country Ⅰ because additional capital has come into the country to be used in the production process • Efficiency of world resource increases because of the free movement of capital • World output increases • Potential benefits and costs of foreign direct investment to a host country • Potential benefits of foreign direct investment • Increased wages • Increased output • Increased employment • Increased exports • Increased tax revenues • Realization of scale economies • Provision of technical and managerial skills and of new technology • Weakening of power of domestic monopoly • Potential costs of foreign direct investment • Adverse impact on the host country’s commodity terms of trade • Transfer pricing • Decreased domestic saving • Decreased domestic investment • Instability in the balance of payments and the exchange rate • Loss of control over domestic policy • Increased unemployment • Establishment of local monopoly • Inadequate attention to the development of local education and skills • Overview of benefits and costs of foreign direct investment • No general assessment • Performance requirements are often placed on foreign firms to improve the ratio of benefits to costs Labor movements between countries • Economics effects of labor movement • Assuming that labor is homogeneous in the two countries and mobile, should move from areas of abundance and lower wages to areas of scarcity and higher wages. • This movement of labor causes the wage rate to rise in the area of out-migration and to fall in the area of in-migration. • Labor continues to move until the wage rate is equalized between the two regions. • Additional considerations pertaining to international migration • The new immigrant might transfer some income back to home country • The nature of the immigration Part 4 Trade Policy The instruments of trade policy Chapter 13 Learning objectives • The different tax instruments employed to influence imports • Familiar with policies used to affect exports • The problems encountered in measuring the presence of protection • The different nontariff policies used to restrict trade Import tariffs • Specific tariffs • A specific tariff is am import duty that assigns a fixed monetary tax per physical unit of the good imported. • Ad valorem tariffs • The ad valorem tariff is levied as a constant percentage of the monetary value of 1 unit of the imported good. • Other features of tariff schedules • Preferential duties– are tariff rates applied to an import according to its geographical source; a country that is given preferential treatment pays a lower tariff. Generalized system of preferences (GSP) • Most-favored-nation treatment (MFN/NTR) It represents an element of nondiscrimination in tariff policy. • Offshore assembly provisions Under offshore assembly provisions(OAP), now referred to as production-sharing arrangements by the U.S. International Trade Commission, the tariff rate in practice on a good is lower than the tariff rate listed in the tariff schedules. Despite the consumer benefits, OAP legislation is controversial. • Measurement of tariffs The “height” of tariffs: One measure of a country’s average tariff rate is the unweighted-average tariff rate; the alternative technique is to calculate a weighted-average tariff rate. “Nominal” versus “effective” tariff rates (ERP): The nominal rate is simply the rate listed in a country’s tariff amount per unit by the price of the good. • Export taxes and subsidies An export tax is levied only on home- produced goods that are destined for export and not for home consumption. An export subsidy, which is really a negative export tax or a payment to a firm by the government when a unit of the good is exported, attempts to increase the flow of trade of a country. • Nontariff barriers to free trade Import Quotas: The import quota differs from an import tariff in that the interference with prices that can be charged on the domestic market for an imported good is indirect. “Voluntary” export restraints(VERs): It originates primarily from political considerations. • Government procurement provisions In general, these provisions restrict the purchasing of foreign products by home government agencies. • Domestic content provisions It attempts to reserve some of the value added and some of the sales of product components for domestic suppliers. • European border taxes The value-added tax (VAT) common in Western Europe is what economists call an “indirect” tax; this tax is passed on to the buyer of the more finished good; Under WTO rules, any import coming into the country must pay the equivalent tax because it too is destined for consumption, and both goods will then be on an equal footing. • Administrative classification The point here is straightforward. Because tariffs on goods coming into a country differ by type of good, the actual tax charged can vary according to the category into which a good is classified. • Restrictions on services trade • Trade-related investment measures • Additional restrictions Developing countries facing a need to conserve on scarce foreign exchange reserves may resort to generalized exchange control. • Additional domestic policies that affect trade The impact of trade policies Chapter 14 Learning objectives • How tariffs, quotas, and subsidies and subsidies affect domestic markets • The winners, losers, and net country welfare effects of protection • How the effects of protection differ between large and small countries • How protection in one market can affect other markets in the economy Trade restrictions in a partial equilibrium setting: the small-country case • The impact of an import tariff • Consumer surplus • Producer surplus • The impact of an import quota and a subsidy to import-competing production • The import quota • Subsidy to an import-competing industry • The impact of export policies • The impact of an export tax • The impact of an export quota • The effects of an export subsidy Trade restrictions in a partial equilibrium setting: the large-country case • Framework for analysis • Demand for imports schedule • Supply of exports schedule • The impact of an import tariff • The impact of an import quota • The impact of an export tax • The impact of an export subsidy Trade restrictions in a general equilibrium setting • Protection in the small-country case • Protection in the large-country case Other effects protection • Lead to a reduction in exports of the tariff-imposing country • Have an impact on the distribution of income among the factors of production • The effect of protection in certain industries on total imports may be less than it appears if only the change in imports of the protected goods is examined ARGUMENTS FOR INTERVENTIONIST TRADE POLICIES CHAPTER 15 Learning objectives • To understand why trade policy instruments • • • are often part of broader social policy and why other policy instruments might be less costly. To evaluate the effectives of trade policy in the presence of market imperfection. To recognize invalid economic arguments for protection. To grasp the role of trade policy in promoting strategic industries and dynamic comparative advantage. 174 Introduction • In principle, most economists at least agree that trade increase the overall well-being of a country, it is striking too note how much individual interests are willing to spend to reduce international trade. • Because most economists think in terms of alternatives and benefits vs costs, our produce is essentially to ask,” Given the objective, what are the benefits and costs of a restrictive trade policy compared with those another policy?” 175 Trade policy instruments are part of broader social policy objectives for a nation-1 • Trade taxes as a source of government revenue The decision to use trade taxes, as opposed to other forms of taxation, to fund government expenditure in this broader social context turns on issues of tax efficiency and equity. • National defense argument for a tariff The important point to recognize is that it is not easy to identify which industries are vital to national defense. 176 Trade policy instruments are part of broader social policy objectives for a nation-2 • Tariff to improve the balance of trade This claims that the imposition of the tariff will reduce imports. Assuming the exports are not affected, the obvious result is that the balance of trade improves • The terms-of-trade argument for protection It maintains that national welfare can be enhanced through a restrictive policy instrument. . 177 Trade policy instruments are part of broader social policy objectives for a nation-3 • Tariff to reduce aggregate unemployment It runs as follows: Given that a country has unemployment in slack time, the imposition of tariff in a shift in demand by domestic consumers from foreign goods to home-produced goods. • Tariff to increase employment in a particular industry It argues that if protection is granted to a given industry, demand shift from foreign goods to home-produced goods. This shift in purchase then bids up the price of home good, inducing domestic producers to supply a greater quantity. 178 Trade policy instruments are part of broader social policy objectives for a nation-4 •Tariff to benefit a scare factor of production It makes no claim that the country as a whole benefits from the protection; it is instead a argument for protection from the perspective of an individual factor of production. 179 Trade policy instruments are part of broader social policy objectives for a nation-5 • Fostering “national pride” in key industries Pride in your country can clearly be thought of as a legitimate social objective. • Differential protection as a component of a foreign policy/aid package This is one that substantially reduces the barriers of trade with respect to goods coming in a certain developing countries. 180 Protection to offset market imperfections-1 • The presence of externalities as an argument for protection Choose the policy that gets directly to the problem. • Tariff to extract foreign monopoly profit Due to the tariff, world efficiency and welfare are reduce . 181 Protection to offset market imperfections-2 • The use of an export tax to redistribute profit from a domestic monopolist The presence of export tax offsets some of the monopoly leverage of the firm as it drives the domestic price downward to MC, expanding domestic consumption and generating government revenue. 182 Protection as a response to international policy distortions • Tariff to offset foreign dumping 1. persistent dumpling 2. intermittent dumpling 3. sporadic dumpling 4. antidumping duty • Tariff to offset a foreign subsidy The basic point is that a foreign government subsidy awarded to a foreign import supplier constitutes unfair trade with the home country. 183 Miscellaneous, Invalid arguments • One common argument is that a country should use protection to reduce imports and keep the money at home. • Another argues for protection to “level the playing field” in the terms of offsetting cheap foreign labor or other reasons for cost differences. In the extreme, it is often referred to as the “scientific tariff”, that is, a tariff that equalizes products costs among countries. 184 Strategy trade policy: Fostering comparative advantage-1 • The infant industry argument for protection The infant industry argument rests on the notion that a particular industry in a country may posses, for various reasons, a long-run comparative advantage even though the country is an importer of the good at the present time. 185 Strategy trade policy: Fostering comparative advantage-2 • Economies of scale in a duopoly framework An important contribution to the strategic trade policy literature came from economist Paul Krugman (1984). His intention is to demonstrate how import protection for one firm leads to an increase in exports for the protected firm in any foreign markets in which that firm operates. 186 Strategy trade policy: Fostering comparative advantage-3 • Research and development and sales of a home firm In considering this tariff to promote exports through R&D, assume again that a duopoly market structure of a home firm and foreign firm exits and that the firms are competing in markets. However, assume that marginal costs for each firm are constant with respect to output but that, for any given level of output, marginal costs depend on investment in R&D. 187 Strategy trade policy: Fostering comparative advantage-4 • Export subsidy in duopoly The analysis again assumes a duopoly context of a home firm and a foreign firm. The firms are competing for sales in the market of a third country, that is, in a market that is not the domestic market of either of the two duopolists; and it assumes that they do not sell any output in their own domestic markets. 188 Strategy trade policy: Fostering comparative advantage-5 • Strategic government interaction and world welfare An important result of this forthcoming analysis is that country governments each can be maximizing their own country’s well-being, given the behavior of other governments, and yet would welfare as a whole is definitely not being maximized. 189 Strategy trade policy: Fostering comparative advantage-6 • Concluding observations on strategic trade policy It was quickly pointed out that while competitiveness is relevant for individual firms, comparative advantage and competition is what is relevant for countries. Further, it is extremely difficult to determine which products might have a potential comparative advantage and hence be the focus of such strategic trade policy. 190 Summery • This chapter has presented and examined many of the most common arguments for protection. • Traditional arguments were grouped into several key categories. • We also examined several of the arguments that focus on the dynamic benefits of protection. 191 POLITICAL ECONOMY AND U.S. TRADE POLICY CHAPTER 16 Learning objectives • To comprehend several basic concepts of the political economic policy. • To understand critical development in the history of multilateral trade negotiations. • To become familiar with recent trade policy issues. • To increase awareness of ongoing U.S. trade policy developments. 193 Introduction • Trade policy can involve conflicting and complex economic and political forces, and outcomes are not so clear cut as traditional trade theory would suggest. • This chapter first addresses how the setting of the trade policy is influenced by the institutions and the political process and then summarize U.S. and multilateral trade policy developments during the last several years. 194 The political economy of trade policy-1 • The self-interest approach to trade policy In this approach, government decision makers are essentially utility maximizes whose level of satisfaction is depend being reelected and who act in a manner that maximizes the probability that this will in fact take place. An immediate implication of this approach is that majority of the public will be served by public decision makers who enact legislation to maximize their chances of remaining in office. 195 The political economy of trade policy-2 • The social objectives approach Trade policy is conducted taking into account the wellbeing of different groups in society along with various national and international objects. In this environment, trade policy is promoted to the public at large in terms of broader social goals such as income distribution, increased productivity, economic growth, national defense, global power and leadership, and international equity. 196 The political economy of trade policy-3 • An overview of the political science take on trade policy From an international relations perspective, it has been tempting for political scientists to focus on the role of chief executive of a country in influencing not only national security but also policy relating to trade. However, this “unitary actor ” approach has been criticized for ignoring the micro foundations of policy formulation that underlie the process by which various pressure groups influence the setting of the policy. 197 The political economy of trade policy-4 • Baldwin’s integrative frame for analyzing trade policy It is built around four major sets of actors: individual citizens, common-interest groups, the domestic government, and foreign governments/international organizations. The domestic government would be viewed as the key actor because it ultimately sets policy. 198 A review of U.S. trade policy-1 • Reciprocal trade agreements and early GATT rounds The long process of tariff reduction began with the passage by Congress of the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934. This act authorized the executive branch to engage in bilateral negotiations with individual trading partners on tariff reductions. • The Kennedy Round of trade negotiations To put new life into the trade negotiation process and to avoid being shut up by te newly forming European Economic Community, the United States led the way into a new round of negotiations from 1962 to 1967. 199 A review of U.S. trade policy-2 • The Tokyo Round of trade negotiations A new impetus for the new round was that, while tariff rates had been moving downward, NTBs had been rising and had offset some of the benefits of the tariff reduction. • The Uruguay Round of trade negotiations Major objectives of this new round included a continuation of the attempt to reduce NTBs, an enlargement of the negotiations to embrace trade in services in addition to the traditional emphasis on trade in goods, and a determination to deal with restrictions on agricultural trade. 200 A review of U.S. trade policy-3 • Trade policy issues after the Uruguay Round Many countries wish to attain further relaxation of trade-restriction measures in agriculture and services, to reduce remaining tariff further, and to consider a variety of other matters pertaining to areas such as antidumping procedures, procedures with WTO, and intellectual property rights. Further, there was a desire by developed countries----but decided not by developing countries---to discuss the broad general area known as “labor standards”. In addition, and again mainly by developed countries, there was pressure to include considerations of the environmental impact of trade. 201 A review of U.S. trade policy-4 • The Doha Development Agenda Promises were made to reduce trade barriers further, including those in the agricultural sector. A particular focus of trade liberalization was to be on making clearer and stricter the rules for imposing antidumping duties. Several of plans for this round were of considerable potential benefit to developing counties, such as the intent to give developing countries cheaper access to pharmaceuticals. 202 A review of U.S. trade policy-5 • Recent U.S. Action United States has, in recent years, been negotiating bilateral and regional trade agreements. As far back as 1985, a U.S.Israel free trade agreement went into effect. In addition, free trade agreement with 10 countries went into effect from 2001-2007, and agreements had been negotiated and talks were underway with still others. Finally, a phenomenon that has caught the attention of American public in the last few years is the phenomenon of outsourcing. 203 Concluding observations on trade policy-1 • The conduct of trade policy A rules-based trade policy is one that adheres to commonly accepted international guidelines and codes of behavior on trade. A results-based trade policy stresses that policy should seek, through aggressive , unilateral action or threat of action, to achieve the objectives. 204 Concluding observations on trade policy-2 • Empirical work on political economy In general, a survey of various empirical tests for the U.S. indicated that a statistically significant positive relationship exits between the degree of industry protection and the number of workers in the industry , and so on. 205 Summery This chapter examined political economy influence, such as interest group and social concern, on trade policy, and considered related empirical work in the context of the U.S.. This was accompanied by a review of U.S. trade policy which highlight the long-run trend of liberalization of trade, first through bilateral and the through multilateral negotiation. 206 ECONOMIC INTEGRATION CHAPTER 17 Learning objectives • To understand the differences between the • • • four basic levels of economic integration. To identify the static and dynamic effects of economic integration. To grasp the real-world impact of economic integration on countries in the European Union and the North America Free Trade Agreement. To increase awareness of current economic integration efforts in the world. 208 Introduction • What precisely is economic integration? What are the benefits that cause all these nations to want to join an economic union? Are there costs involved? • In this chapter, we discuss several different types of economic integration, present a framework for analyzing the welfare impacts of these special relationships, and examine recent economic integration efforts in the world. 209 Types of economic integration -1 • Free Trade Area All members of the group remove tariffs on each other’s products, while at the same time each member retains its independence in establishing trading policies with nonmembers. This scheme is usually assumed to apply to all products between member countries, but it can clearly involve a mix of free trade in some products and preferential, but still protected, treatment in others. 210 Types of economic integration -2 • Customs Union All tariffs are removed between members and the group adopts a common external commercial policy toward nonmembers. Further more, the group acts as one body in the negotiation of all trade agreements with nonmembers. The existence of the common external tariff takes away the possibility of transshipment by nonmembers. 211 Types of economic integration -3 • Common Market All tariffs are removed between members, a common external trade policy is adopted for nonmembers, and all barriers to factor movements among the member countries are removed. The free movement of labor and capital between members represents a higher level of economic integration and, at the same time, a further reduction in national control of the individual economy. 212 Types of economic integration -4 • Economic Union Includes all features of a common markets but also implies the unification of economic institutions and the coordination of economic policy though out all member countries. While separate political entities are still present, an economic policy union generally establishes several supranational institutions whose decisions are binding upon all members. When an economic union adopts a common currency, it has become a monetary union as well. 213 The static and dynamic effects of economic integration • Static effects of economic integration • General conclusions on trade creation/diversion • Dynamic effects of economic integration • Summery of economic integration 214 The European Union • History and structure • Growth and disappointments • Completing the internal market • Prospects 215 Economic disintegration and transition in central and eastern European and the former Soviet Union • Council for Mutual Economic Assistance It was began in 1949 to promote economic cooperation among the member countries as a Soviet counterpart to Marshall Plan. • Moving toward Market Economy The challenges for these transition economies of moving into the world trading system begin with the need for a generally acceptable and convertible currency. The issue of products quality is also a major concern. 216 North American Economic Integration • Greater Integration NAFTA eliminates tariff among the three member countries over a 15-year period and at the same time substantially reduces nontariff barriers. NAFTA was the first regional agreement among counties with such diverse income levels. • Worries over NAFTA Estimates of the employment varied. The precise size of other impacts of NAFTA is also questionable. 217 Other major economic integration efforts • MERCOSUR • CAFTA-DR • FTAA • Chilean Trade Agreements • APEC 218 Summery • This chapter examined the theory behind the formation of various types of Economic Integration. • When a discriminatory trade policy regime of this sort is induced, trade is created through displacement of highcost domestic producers by lower-cost partner supplier. • This chapter also gave attention to the EU, NAFTA, and other projects like CEMA ,and so on . 219 INTEGRATIONAL TRADE AND THE DEVELOPING COUNTRIES CHAPTER 18 Learning objectives • To become familiar with the various • • • characteristics of developing countries. To learn how great openness to trade can potentially contribute to more rapid economic growth. To understand the problems of export instability and terms-of-trade deterioration faced by developing countries. To comprehend the nature of and potential solutions to the external debt problems of developing countries. 221 Introduction • How might the changing economic conditions described in this vignette be related to international trade and finance? • The purpose of this chapter is to explore these relationships. 222 An overview of developing countries-1 • A closer look at the least developing countries Kirchbach(2001) identified four accepted stylized facts about international trade relations of the least developed countries that do not necessarily reflects current realities: 1. Trade/GDP rations are low in the least developed countries. 2. All least developed countries export primary commodities. 3. All least developed countries suffer from marginalization from global trade flows, and this tendency is inexorably increasing. 4. All least developed countries have closed trade regimes. 223 An overview of developing countries-2 • The ratio of trade to GDP According to 1997-1998 data, exports and imports of goods and services constituted an average of 43 percent of their GDP. This average level of trade integration for the least developed countries was around the same as the world average and actually higher than that of higher-income OECD countries. • Primary commodity exports For the least developed countries as a group, unprocessed primary commodities constituted 62% of total merchandise exports and processed primary commodities made up a further 8% of merchandise exports. 224 An overview of developing countries-3 • Marginal from global trade flows The concept of marginalization is based on a fear that globalization result in a greater concentration of international trade and investment flows and that the benefits accrue to only a small number of countries. • Closed trade regimes There is some evidence that suggests that least developed countries have gone further in dismantling trade barriers than other developing countries. • Trade liberation, growth, and poverty The lack of trade liberalization has also been called into question. 225 The role of trade in fostering economic development-1 • The static effects of trade on economic development If there is a difference between internal relative prices in autarky and those can be obtained internationally, then a country can improve its well-being by specializing in and exporting relatively less expensive domestic goods and importing goods that are relatively more expensive. 226 The role of trade in fostering economic development-2 • The dynamic effects of trade on economic development Because conditions in the developing countries differ so dramatically from theoretical world of perfect competition and full employment utilized in many theoretical models, the static application of comparative advantage may not be very helpful in providing guidelines for trade and specialized in dynamic LDC setting. 227 The role of trade in fostering economic development-3 • Export instability Whether the focus is on prices or on earnings, however, the variability is regarded as a problem because, with the relatively high degree of openness of many developing countries, variability in export sector is often associated with variability in GDP and the domestic price level. 228 The role of trade in fostering economic development-4 • Potential causes of export instability All three reasons are associated with the fact that many developing countries are relatively more engaged in the export of primary products than manufactured goods. The first two reasons pertain to price variability, while the third reason focuses on total export earnings variation. 229 The role of trade in fostering economic development-3 • Long-run terms-of-trade deterioration 1. Differing income elasticity of demand 2. Unequal market power 3. Technical change 4. Multinational corporations and transfer pricing 230 Trade, Economic growth, and Development: the empirical evidence-1 • International export quota agreement A type of agreement exemplified historically by the international Coffee Agreement and, less rigidly, by the Association of Coffee producing countries, which operated from 1993-2002. • Compensatory financing An international agency is provided with funding and forecasts the growth trend of the export earnings of each participating LDC. 231 Trade, Economic growth, and Development: the empirical evidence -2 • In sum, while empirical analysis often supports the idea of a positive connection between the expansion of international trade and growth in income. • The manner and degree to which trade influences growth and development is complex and often country specific. The nature of the effect appears to vary with the degree of development, the nature of the economic system, and world market conditions outside the influence of the individual country. 232 Trade policy and the developing countries-1 • Policies to stabilize export prices or earnings 1. International buffer stock agreement 2. International export quota agreement 3. compensatory financing • Problems with international commodity agreements From the standing point of the feasibility, the crucial feathers for success in a buffer stock agreement are the level at which the ceiling price and the floor price are set. 233 Trade policy and the developing countries-2 • Suggested polices to combat a long-run deterioration in the terms of trade 1. Export diversification 2. Export cartels 3. Import and export restrictions 4. Economic integration projects • Inward-looking vs. outward-looking trade strategies It is an attempt to withdraw, at least in the short run, from the full participation in the world economy. This strategy emphasize import substitution, that is , the production of goods at home that would otherwise be imported. 234 The external debt problem of the developing countries-1 • Causes of the developing countries’ debt problem 1. oil shock 2. recession in the IC in the 1970s and early to mid-1980s 3. real interest rate 4. primary-product prices 5. domestic policies 6. capital flight 7. loan-pushing by banks in DC 235 The external debt problem of the developing countries-2 •Possible solutions to the debt problem 1. changing domestic policies 2. debt rescheduling 3. debt relief 4. debt equity swaps 236 Summery • The LDC in the world economy are characterized • by relatively low levels of per capita income, a relatively high concentration of exports of primary products, and export instability; they may also face long-run forces that cause a deterioration in their commodity terms of trade. Along with trade problems, many DC face problems with serving and repayment of external debt. Recent steps have begun to emphasize some elements of debt forgiveness to reduce the potential burden of debt upon the growth process. 237 T h a n k y o u