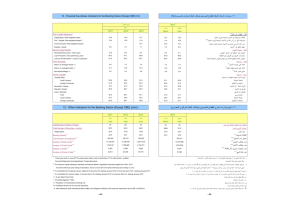

I. The Lithuanian Banking System 3 - Documents & Reports

advertisement