Business Case

Business Case and Intervention Summary

Intervention Summary

Financial Sector Development in Nigeria – Extension and Scale-Up

What support will the UK provide?

The UK Government will continue to support increased access to financial services by making the market for financial services work better for the poor, and by improving regulation in

Nigeria. Financial stability and access to finance contribute to the Golden Thread: supporting open economies and open societies, in which poor women and men are less excluded from financial services and more able to secure wealth creating opportunities.

This Business Case is for extending and scaling-up the successful Financial Sector

Development programme in Nigeria with an additional £26.45 million of support for the period

1 April 2013 to 31 December 2017. This builds on the previous commitment of £9.67 million for the period 10 October 2006 to 31 December 2012 and £2.05 million of ‘bridging funding’ recently approved by Secretary of State for the period 1 October 2012 to 31 March 2013, bringing the programme total to £38.17 million.

The programme scale-up will deliver one of eight DFID Nigeria Operational Plan headline results, namely of contributing to 10 million additional people in Nigeria having access to financial services by 2015. This is a fifth of DFID’s corporate ‘We Will’ commitment of supporting 50 million people worldwide to gain access to financial services.

The programme received a score of A+ ‘preforming moderately above expectations’ (the second highest score) in its Annual Review and an excellent value-for-money assessment, exceeding that of all other comparable DFID-funded programmes. Provisional data indicates the programme has exceeded its milestone target for 2012.

The Financial Sector Development Programme has two components:

1. Support to Enhancing Financial Innovation and Access (EFInA), a not-for-profit company set up by DFID in 2008 to promote financial inclusion and increase access to financial services in Nigeria, provided through an accountable grant. (EFInA is currently also part-funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation). This is the major component.

2. Technical support to the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and other financial sector regulators to support financial sector stability and investor confidence, provided through a trust fund with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to provide long term technical advisers.

Under the proposed scale-up, £20.78 million of funding will be allocated for EFInA (79 per cent of the total); £3.67 million for Technical Support to Regulators (13 per cent); and £2 million for project management, monitoring and evaluation, and research (8 per cent).

1

Why is UK support required?

Nigeria has a population of 160 million people, of whom around 100 million people live on less than $1.25 a day. Nigeria has a relatively developed commercial banking sector serving the oil and corporate sectors, but failing to serve the wider economy and the vast majority of

Nigerians. The sector is still dealing with the ramifications of a banking crisis and a stock market crash in 2008, which revealed fundamental weaknesses in the regulatory frameworks.

Access to Financial Services

Access to credit, savings and payment services provides opportunities for poor men and women to better manage their income and assets, especially in a crisis, and to take advantage of wealth creating opportunities.

Two thirds of Nigerian adults - 54 million people - do not have access to formal regulated financial services. The vast majority, 80 per cent, of this group live in rural areas, predominantly in Northern Nigeria. Low population densities and low household incomes in these areas make conventional financial products and services, delivered through bank branches, expensive to deliver and unattractive to service providers.

The high costs to consumers of traditional banking services (service fees, minimum account requirements, time and money required to travel to a bank branch), the absence of products suitable for people with erratic or irregular income, and inability to provide documents and information required by banks (official identification documents, records of their financial transactions) are barriers to poor people using formal financial services. The microfinance sector is very weak, poorly regulated and with little potential for scale in Nigeria. New and innovative approaches are needed to provide access cost-effectively at the scale Nigeria requires.

Continuing UK support to EFInA offers the best prospects for achieving financial inclusion in

Nigeria. EFInA has established itself as the leading promoter of innovation for financial inclusion both with regulators and with the finance sector. It has been the driving force behind the regulatory reforms which opened up mobile payments, mobile banking, agent banking

(using retail agents and other responsible parties to act as cashiers for banks) and Islamic

(noninterest) finance in Nigeria. It supported and advised on Nigeria’s Financial Inclusion

Strategy, which was launched on 23 October by President Jonathan and the Governor of the

Central Bank.

DFID established EFInA as an independent nor-for-profit company with a Nigerian identity for sustainable impact. The Chairman of the Board is the Chairman of Citibank in Nigeria. It employs twelve members of staff directly and two secondees from the German Agency for

International Cooperation (GiZ) to bolster its technical capacity. No other donor agencies occupy this space in Nigeria.

Financial Sector Stability

Effective financial sector regulation contributes to financial stability, avoiding financial crises, continuing investor confidence, and maintaining economic growth. The median estimate for

2

GDP loss resulting from a serious financial crisis is around 60 per cent of annual GDP 1 .

In 2008 the global financial crisis precipitated a major banking crisis and stock market crash in

Nigeria. Even though the Governor of the Central Bank - a key reformer in Nigeria - acted quickly and decisively to sack eight bank chief executives, restructure failing banks and announce new regulations, GDP loss was estimated to be in the order of 5 per cent.

DFID supported advisers filled gaps in the Central Bank’s capacity to respond to the immediate problems by 1) setting up the Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria (AMCON) to buy and r estructure ‘toxic assets’ from troubled banks, and 2) to design and introduce a risk-based banking supervisory framework to replace the inadequate ‘tick box’ approach. This support has had substantial impact on the regulatory frameworks, policies and operations of the Central Bank and other regulators. However, continuing support is required to establish fully practical frameworks across the regulatory agencies.

DFID provides this support through a grant agreement and trust fund with the IMF, making use o f the IMF’s technical expertise. The IMF recruits, manages, monitors and evaluates up to four long term expert advisers placed within the Central Bank and its agencies.

What are the expected results?

Our support will promote and facilitate change in the financial sector to be more inclusive, providing products and services which are more accessible, affordable and used by more people to conduct household and business transactions at a lower cost, manage income and assets, manage risk and shocks, save or borrow to invest in wealth creating opportunities.

EFInA will contribute to an additional 12 million people having access to formal financial services , of whom 50% will be women, over the period 2010

– 2017, as a result of generating and disseminating credible market information, stimulating opportunities for innovation amongst private sector providers of financial services, identifying and addressing obstacles to innovation through advocating for policy and regulatory reform, and funding the development of innovative and accessible products and services.

Technical support to regulators will ensure the new risk-based regulatory policies and frameworks are introduced and effectively implemented across the regulatory agencies and the Asset Management Corporation can dispose of ‘toxic assets’ fairly and efficiently as a result of long term advisers developing procedures and building the capacity of the agencies

The programme’s track record and recent Annual Review provides confidence that the programme can deliver these results and with good value for money: at a cost of

£2.49 per beneficiary having access to financial services through EFInA. Comparison with a number of similar DFID-funded Financial Sector Development programmes in other countries shows

EFInA to provide the best value for money of all.

1 Cecchetti, Stephan G., Strengthening the financial system: comparing costs and benefits, Bank of

International Settlements, September 2010, p.2.

3

Business Case

1. Strategic Case

A. Context and need for a DFID intervention

1. Nigeria has a population of 160 million people, of whom around 100 million people live on less than $1.25 a day. Access to credit, savings and payment services provides opportunities for poor men and women to better manage their income and assets, especially in a crisis, and to take advantage of wealth creating opportunities 2 .

2. Almost 64 per cent of Nigerian adults , 54 million people, do not have access to formal regulated financial services.

A substantial minority, 17 per cent or 15 million adults, have access only to informal unregulated and often insecure financial services such as savings and loans clubs and cooperatives 3 .

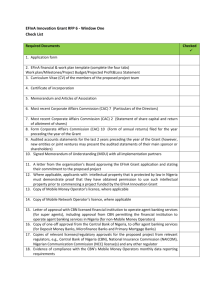

Figures 1 and 2: Access to Finance in Nigeria, 2010

4.

3. The situation is worse for women, in rural areas and in the North . Twenty nine million women do not have access to formal financial services. This is 52 per cent of women compared to 41 per cent of men 4 .

The commercial banking sector is serving the oil and corporate sectors, and wealthy individuals, but failing to serve the wider economy and the vast majority of Nigerians. Financial markets are shallow and the ratio of domestic credit to GDP is less than in comparator countries such as Kenya and South Africa 5 .

5. In 2008 the global financial crisis precipitated a major banking crisis in Nigeria, prompting consolidation of the sector and major changes in financial regulation, but

2 Pande, Cole, Sivasankaran, Bastian and Durlacher; (2011) “Does Poor People’s Access to Formal Banking

Services Raise their Incomes?” , Harvard University

3 EFInA Access to Financial Services in Nigeria 2010 Survey

4 EFInA Access to Financial Services in Nigeria 2010 Survey

5 World Bank (June 2011) Nigeria 2011: An Assessment of the Investment Climate in 26 States

4

leaving much of the sector more risk averse. At the same time, mobile phone penetration grew rapidly to 58 per cent of adults 6 and various players geared up to enter the nascent mobile payments market. New opportunities for financial inclusion emerged.

6. The vast majority of those without access to any financial services live in rural areas, predominantly in the North, where low population density and low incomes make traditional banking services expensive to deliver and unattractive to the commercial banking sector 7 . The transaction costs are high, whilst returns from customers with small deposit and loan accounts are low 8 . A high volume of accounts and / or low transaction costs are required to make low income segments attractive to service providers.

7. In addition to the high costs to consumers of traditional banking services (service fees, minimum account requirements, time and money required to travel to a bank branch), the absence of products suitable for people with erratic or irregular income, and inability to provide documents and information required by banks (official identification documents, records of their financial transactions) are barriers to poor people using formal financial services.

8. The gap is often filled by microfinance banks and other microfinance service providers but the sector is particularly weak in Nigeria. Only 3.2 million adults have a microfinance bank account. Service providers are small with an average of 10,145 borrowers and 30,331 depositors and typically unprofitable with poor quality portfolios and negative rates of return on assets.

9

9. New business models, new products and services such as mobile banking, using new distribution channels such as agents acting as cashiers for banks, and electronic payment systems which are cheaper than the costs of handling cash, offer the best prospects for achieving change at the scale Nigeria needs.

10. The banking crisis in 2008 has driven some commercial banks to look for new markets and new sources of revenue. At the same time, whilst the banking sector has been struggling, mobile phone penetration has grown rapidly and various players geared up to enter the nascent mobile payments market. The cost to services providers of mobile transaction to can be as much as 80% less than the costs of branch and Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) transactions 10 .

11. There are now over 100 million active mobile phone lines in Nigeria. Fifty million adults, 58 per cent, own a mobile phone and even 40 per cent of the lowest income groups own a mobile phone 11 . Although under Nigerian regulations Mobile Network

6 EFInA Access to Financial Services in Nigeria 2010 Survey

7 EFInA Access to Financial Services in Nigeria 2010 Survey

8 The average size of loan and deposit accounts in Nigerian microfinance service providers (MSPs) 8 is just $428 and $58 respectively 8

9 MixMarket data shows the median portfolio at risk ratio (<30 days) for microfinance providers in SSA is

5.80% compared to 1.92% in South Asia. Concurrently, the median level of risk coverage is just 53.2% in SSA compared to 98.4% in South Asia.

10 CGAP Technology Programme

11 EFInA Access to Financial Services in Nigeria 2010 Survey

5

Operators are not allowed to establish money transfer or ‘mobile money’ schemes without partnering with a Bank or other licensed service provider, which is slowing down wide spread roll out of these services in Nigeria.

12. There is growing policy attention in the access to finance agenda, particularly by the

Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) which has recently published a Financial Inclusion

Strategy and introduced “cash lite” policy to reduce reliance on cash and help

“reduce the cost of banking services and drive financial inclusion by providing more efficient transactions”.

13. DFID Nigeria, and EFInA, have very good relationships with and access to the

Central Bank Governor – a key reformer in Nigeria and Central Bank Governor of the Year in 2011 12 . Other donor funded programmes do not have the breadth and depth of ambition, the focus on innovation, or the credibility and influence with policy makers which DFID and EFInA have developed.

Box 1: DFID’s response to Market Failures in Financial Markets

Financial markets suffer from a variety of market failures: imperfect information, returns to scale and costs of small transactions, segmented competition and externalities. Where there is a market failure, there are two possible responses: fix the market (if it is fixable) or substitute for it through some kind of direct intervention. In the past governments and supporting development partners often opted for the latter strategy (direct provision) without seriously considering the prospects for achieving the former (improving the working of the financial market).

DFID’s Financial Sector Deepening Trusts take a different approach: supporting governments to take action to tackle the numerous systemic constraints in improving access to finance at three different levels:

Reforming the existing policy, legal and regulatory system at the macro level

Taking action to develop the markets and promote business models of relevance to poor households and other excluded segments at the meso level

Intervening in the market itself to promote financial services at the micro level.

B. Impact and Outcome that we expect to achieve

14. The outcome we expect to contribute to is a more stable and more inclusive financial sector, providing products and services which are more accessible, affordable and used by more people to conduct their financial transactions, manage their income and assets, especially in a crisis (financial resilience), and take advantage of wealth creating opportunities, with a subsequent impact on incomes and economic growth.

15. The measurable outcome of our total contribution is an additional 12 million people will have access to formal financial services , of whom 50% will be women, over the period 2010

– 2017, of which 7.7 million between 2012 and 2017. This will deliver our Operational Plan target for 2015 of 10 million people.

16. Provisional results for 2012 are that 5 million more people have access to finance than in 2010 13 , more than the milestone target of 4.3 million people. This gives us

12 The Banker (23/12/2010) http://www.thebanker.com/Awards/Central-Bank-Governor-of-the-Year/Central-

Bank-Governor-of-the-Year-2011

13 This is a provisional result from the EFInA Access to Financial Services in Nigeria 2012 Survey which is currently having final checks before being launched on 22 November 2012.

6

confidence that the programme will deliver the Operational Plan results, but we will ensure that the programme targets remain challenging.

Table 1: Outcome Targets, 2010-2017, Additional People with Access to Financial Services, millions

2010

Cumulative Target Baseline

2012 2013 2014 2015

+4.3

EFInA 2010 - 2017 Total

+10.0

2016 2017

+12.0

+2.0 Incremental Target Baseline +4.3 +5.7

DFID Nigeria Operational Plan Target

Cumulative Target Baseline +4.3 +10.0

Incremental Target Baseline

Cumulative Target

+4.3 +5.7

Business Case and EFInA Five Year Strategy Target

Baseline +4.2 +5.7 +7.7

Incremental Target Baseline +4.2 +1.5 +2.0

17. We will assess our contribution to these outcomes by monitoring and reporting the increases in access to and usage of financial products and services on which EFInA has engaged, as well as the headline increase in access to finance.

18. Technical support to the CBN and other financial sector regulators will continue to contribute to more effective regulation and protection for savings and investments, financial stability, a conducive investment climate, and continued GDP growth.

19. The recent Annual Review found th e support has had “substantial impact” on the operations of the CBN 14 . Although much has been achieved, the reforms are not yet fully embedded in the CBN practice and culture. It recommended that DFID continues to support technical experts to assist the CBN with policy implementation.

20. The impact of this support can be viewed in terms of the potential impact of further financial crises or instability. The median estimate for GDP loss resulting from a serious financial crisis is around 60 per cent of annual GDP 15 . Even though the crisis was to some extent pre-empted in Nigeria, GDP loss was estimated to be in the order of 5 per cent.

14 EFInA Annual Review 2012, Report prepared for DFID Nigeria by Hennie Bester, April 2012

15 Cecchetti, Stephan G., Strengthening the financial system: comparing costs and benefits, Bank of

International Settlements, September 2010, p.2.

7

2. Appraisal Case

A. What are the feasible options that address the need set out in the Strategic Case?

21. The feasible options considered are:

1. Continue support to EFInA but cease technical support to the regulators

2. Continue to support EFInA and technical support to the regulators

3. Do nothing (cease both)

22. It would not be proportionate to consider new programmes or to generate artificial options when there is a successful programme on the ground, delivering good results and value for money, and a large results target to deliver. We should build on our investment in the current programme, the relationships, influence, systems and capabilities the implementing partners have built up. The current programme received a score of A+ and an excellent value for money assessment in its recent

Annual Review (Annex B). It has previously received scores of 1 in 2011 and 2 in

2010. The programmes achievements are discussed below.

23. DFID established EFInA as an independent company limited by guarantee to implement financial sector development and inclusion programmes with a Nigerian identity and a long term perspective. Having invested in this model and EFInA’s startup costs in 2008, it would not be efficient or cost effective to establish a new programme or format now

; such a move may damage DFID’s reputation and undermine progress on financial inclusion. Instead we asked EFInA to consider alternative interventions and strategies for delivering the outcome results. This is discussed briefly below and more fully in Annex C, EFInA Five Year Strategy.

Option 1: Continue support to EFInA

24. EFInA has established itself a highly influential promoter of financial inclusion both with financial regulators and with the financial sector and has a respected role as an

“honest broker”. It does so by:

generating and disseminating credible market information, for example through the bi-annual Access to Financial Services in Nigeria Survey

stimulating opportunities for innovation amongst private sector providers of financial services, for example through bringing the founder of M-PESA to share experience with Nigerian companies

identifying and addressing obstacles to innovation through advocating for policy and regulatory reform and facilitating working groups

grant funding for innovative projects , such as Diamond Bank’s savings product for women and Nigerian start-up company

Paga’s mobile banking platform.

25. Commercial users of EFInA’s market information and research describe EFInA as the “’go-to’ for defensible data 16 ” on the demand for financial services in Nigeria; and say: “I do not know where banks would be without them (EFInA)… our entire retail

16 Interview with Jay Alabraba, Paga, on 20 March 2012

8

team uses their information” 17 .

26. EFInA’s greatest successes to date have been in the area of policy and regulation advocacy. It has already achieved significant change in three discrete areas of financial sector regulation: mobile payments, Islamic Finance, and card and ATM fraud. The Annual Review found that “EFInA is without doubt the catalytic force behind the regulatory reforms that has opened up the Islamic Finance sector in

Nigeria” 18 .

27. EFInA’s Innovation Fund took off in 2011 with four Innovation Grants and one

Technical Assistance Grant, in contrast to only two grants in the previous period.

This change has come about because the requests for proposals are now targeted at priority sectors in which EFInA has established relationships and ‘prepared the ground’ for innovation through advocacy and innovation fora.

28. Over the next five years, EFInA will build on the ground work to date but will take a more focussed, more strategic approach. It continue with its operating model and main activities and outputs, which have been successful to date, but will now apply these activities within a narrower focus in three strategic programme areas:

building networks of agents - to act as cashiers and distributors

building inclusive electronic systems for retail payments - card payments, mobile payments etc

as platforms for inclusive financial products and service - non interest banking products, mobile money transfers etc. and to three cross-cutting themes :

women and Northern Nigerians – disproportionately excluded groups which are important priorities for DFID

financial capability – education to increase awareness, understanding and usage of financial products and services.

29. EFInA will investigate establishing a “scale fund” to complement the current innovation funds. This will support the distribution of financial products and services as scale in areas with low population density, perceived as high risk, or are otherwise less attractive to the commercial sector. It is most likely the fund will support the development of agent networks in the North and if so EFInA will have a target for proportion of agents supported by the scale fund which are located in the North.

30. Detailed theories of change for each of EFInA’s strategic areas of focus are provided in its five year strategy. The overarching theory of change for EFInA is depicted below.

17 Interview with Daniel Akumabor, Diamond Bank, and his team on 3 March 2012.

18 EFInA Annual Review 2012, Report prepared for DFID Nigeria by Hennie Bester, April 2012

9

EFInA: Theory of Change

OUTPUTS

Market Information

Advocating Better

Policy & Regulation Unblock

Support for

Innovation

Support for Scale

Efficient Payments

Systems

New Financial

Products

Reach

New Distribution

Channels

OUTCOME

New Customers

(Access to Finance)

Use for

Making

Transacations

Managing Income and Assets

Leads to

Investing in wealth creatiing opporttunities

IMPACT

Improved Financial

Resilience to shocks

Increased Incomes

31. Electronic payments systems which reduce transaction costs and distribution networks of banking agents close to communities are vital infrastructure to deliver financial services cost effectively and at scale in a country where 54 million adults do not have access. These systems can also support the cost effective delivery of other

DFID Nigeria programmes such as Child Development Grants. Supporting new products and services targeting under-served groups without tacking the major barriers to access is unlikely to deliver increased access to finance at the scale DFID has committed to.

32. The decision to focus on just a few strategic and complementary areas and the identification of these areas reflects the need to prioritise and builds on EFInA’s existing capacity and experience to date. As a result the following products and services have been discarded as priorities because they cannot reach a minimum of

2.5 million people or because EFInA cannot rapidly develop capacity: savings, cooperatives, microfinance, microinsurance, housing finance, SME finance 19 .

33. Concentrating on payments systems and agent networks is, however, potentially risky. The focus on payment systems is considered medium risk because the infrastructure is nascent in Nigeria and progress requires CBN investments and support. The risks are mitigated by EFInA work to date.

34. The focus on agent networks is considered medium to high risk because it is a relatively new area for Nigeria and for EFInA. Banks maybe too risk averse in the current climate to pioneer agent banking and expose themselves to the financial and reputational risks of investing in and relying upon agents. On the other hand, new service providers are entering the mobile transfers market, and banks are looking for new markets and new sources of revenue.

35. EFInA will have the tools and capacity to help mitigate the perceived and actual risk to banks and other financial services providers of investing in agent banking. EFInA, with a reputation as an honest broker, is well positioned to help forge partnerships

19 The prioritisation tool and application to these sectors can be seen in Annex C EFInA Five Year Strategy

10

between agent networks, payment platforms, banks and other service providers.

36. Moreover, EFInA will manage its own risk of having a more narrow focus (according to its risk management strategy) by being nimble enough to re-profile its focus across its strategic areas or change course into new strategic areas if necessary.

Option 2: Continue to support EFInA and Technical Support to the Regulators

37. DFID Nigeria has supported the Central Bank (CBN) on monetary operations, banking supervision and banking resolution (dealing with ‘toxic assets’), and supported the Securities and Exchange Commission on capital market regulation.

Initially, this support was to institute a more effective and risk-based approach to banking supervision (as opposed to the previous “tick box” approach) and build capacity within the CBN to effectively supervise banks using a risk-based framework.

The scope of the support has adapted to new needs.

38. This support is highly complementary to EFInA’s activities by contributing 1) to consumer confidence in the sector through adequate protection of savings and investments, and 2) to the sectors confidence in the stability of the investment climate for expanding to serve new, potentially risky markets.

OUTPUTS

Technical Support to Regulators: Theory of Change

OUTCOME

IMPACT

Risk analysis

Tecnhical

Assistance

Capacity Building

Better Regulatory

Frameworks, Systems and Capacity

Improved Risk

Management

Financial Sector

Stability

Confidence in the

Financial Sector

Reduced risk of financial crisis

Continued/ increased

Investment

Continued GDP growth

39. Technical assistance to the CBN and its Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria

(AMCON) is provided through a trust fund with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to recruit and place expert advisers within the organisations. This has been very effective way of bringing specialist expertise to bear on the policies and practice of the regulators. A similar approach has been taken to supporting the Securities and

Exchange Commission but the expert advisers have been recruited and placed by a different DFID Nigeria project, the Policy Development Fund. This support will be brought under the Financial Sector Development programme to ensure it is aligned with the objectives of the programme and supervised effectively.

40. Initially, this support was to institute a more effective and risk-based approach to banking supervision (as oppose d to the previous “tick box” approach) and build capacity within the CBN to effectively supervise banks using a risk-based framework.

The scope of the support has adapted to new needs.

41. The technical support on banking supervision and banking resolution has had substantial impact on the operations of the CBN including:

establishment of a new risk-based banking supervisory framework (approved by the Governors’ Committee as the formal CBN banking supervision framework);

11

institutionalisation and operationalization of the new framework through developing operating guidance and instructing at 18 weeks of training;

assistance to the Nigeria Insurance Commission, the Pensions Commission, the

Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Securities and Exchange

Commission with the development of their risk-based supervisory frameworks.

setting up of the Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria to buy and manage

‘toxic assets’ from troubled banks.

identification of funding devices for purchasing non-performing loans and recapitalising banks.

42. Support for monetary policy implementation has strengthened institutional arrangements for monetary policy implementation, improved data availability for effective decision-making, and strengthened operations in the domestic money market and foreign exchange market. The Liquidity Forecasting and Analysis Office was established to strengthen the liquidity forecasting framework for monetary operations, a new Data Analytics Office was established which is responsible for all data issues within the Financial Markets Department of the CBN. The advisor worked with the CBN to the introduce the Nigerian Master Repurchase Agreement which provided a basis for transactions conducted by the CBN and between counterparties in the money market.

43. The recent Annual Review found that the expertise provided addresses gaps at the heart of the CBNs role as banking supervisor and manager of monetary policy.

Although much has been achieved, the reforms are not yet embedded fully in the

CBN practice and culture. It recommended that DFID continues to support technical experts to assist the CBN with policy implementation:

Continue rolling out the new risk-based supervision framework to other regulatory agencies

Develop and ins titutionalise AMCON’s operating systems and procedures for disposal of ‘toxic assets’

Establish a monitoring and reporting framework for the bank resolution process.

44. The CBN requested that the support be continued in all three areas. It is important that the support on banking supervision and resolution is completed if it is to achieve the outcome of financial sector stability and investor confidence. DFID Nigeria will consider whether further support on monetary operations should be provided or whether other identified areas of potential need such as wholesale payment systems and risk based regulation of Microfinance Banks are more complementary to EFInA’s activities.

45. DFID Nigeria will look for opportunities to work with the International Finance

Corporation and the World Bank in Nigeria to develop other aspects of Nigeria’s financial infrastructure and to address other needs and opportunities which arise.

Option 3: Do Nothing

46. In the absence of EFInA, access to finance in Nigeria would probably continue to increase in the short term as the finance and mobile phone sectors continued to respond to the recent and forthcoming opportunities in mobile payments and transfers and Islamic Finance. This response would be at a slower pace and at a

12

smaller scale without EFInA support and encouragement to realise these opportunities. Moreover, in the longer term, the rate of growth in access to finance may dry up without EFInA driving the changes which create new opportunities for the finance sector.

47. Other bilateral donor’s support to access to finance is limited to particular States, to the microfinance sector (GiZ), or to particular sectors of the economy (USAID). The

International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the World Bank are active in the policy and regulatory sphere and in building Nigeria’s financial infrastructure (such as credit bureaus). In the absence of EFInA, we would encourage the IFC and the World Bank to do more, however these institutions do not have the credibility and influence which

EFInA has developed, and are relatively slow with little dynamism.

48. In the do nothing scenario, support to increasing access to finance for Nigerians would be smaller in scale and narrower in scope, with less attention to women and the North, and without a focus on innovation and exploiting opportunities for providing low cost financial services at the scale Nigeria needs.

49. In the absence of completing the scope of the current support to the CBN and other regulatory agencies, there is a risk that policies and frameworks developed recently are not established fully within the regulatory agencies and weaknesses in financial sector regulation remain with the concurrently greater risk of financial instability.

Opportunities to further improve regulation and investor confidence will be lost.

50. In the absence of approved funding provision DFID Nigeria will be less able to respond quickly to new needs for regulatory support, for example to respond to any ripple effects from a ‘Euro Crisis’ or uncertainty in global financial markets, and opportunities to support financial sector stability and financial infrastructure in

Nigeria.

B. Assessing the strength of the evidence base for each feasible option

51. This section concentrates on the major component of the programme. It evaluate the evidence supporting the EFInA theory of change above in two steps:

at the output to outcome level, using ‘internal’ programme level evidence and

‘external’ research and evidence to consider whether the programme will deliver the outcome result of 12 million people with access to financial services, and

at the outcome to impact level, using ‘external’ research and evidence to consider whether the outcome will allow have a positive impact on household income and resilience to shocks and crises.

Option Evidence Rating

Evidence that the programme outputs will deliver outcomes

Strong

Evidence that the outcomes will have the anticipated impact

Medium 1. EFInA

2. EFInA and

Technical Support

Strong Medium

13

52. At the outputs to outcome level, evidence is used to assess whether EFInA’s interventions influence and clear obstacles for financial services providers and whether financial service providers respond by introducing or expanding products and services which are more accessible, affordable and used by more people.

53. The programme level evidence - successful track record and recent Annual Review - is strong and positive, showing that EFInA’s interventions influence and clear obstacles for financial service providers, and financial service providers do respond.

External research and evidence validating the rationale for the particular areas for intervention - electronic payment systems and agent banking as platforms inclusive products and services such as mobile money transfers, mobile banking, and noninterest finance - is reasonably strong, despite these being new and innovative approaches, and positive.

54. At the outcome to impact level, evidence is used to evaluate whether access to electronic and mobile payment services, banking and other products and services results in consumers using these services to make cheaper transactions, manage income and assets more securely and more effectively e.g. through saving, access credit, invest savings or loans in wealth creating opportunities, and ultimately increase financial resilience to shocks and increase incomes. This evidence is incomplete

– despite a recent systematic review by the Harvard Kennedy School for

DFID of 12 studies, covering ten policies or programmes, which it considered had robust impact evaluation methodology -- but largely positive.

55. For convenience, the external evidence is structured by intervention area and then, according to the steps in the theory of change where evidence is available.

C. Evidence to Support the Theory of Change

56. Poor households’ high reliance on cash is noted by the Bill and Melinda Gates

Foundation as being a key contributor to their ‘marginalisation’ from financial services 20 . Cash is expensive to print, transport, store and protect from loss 21 .

Electronic payments or transaction services are much cheaper to provide than cash transactions. Electronic payments include debit card payment, internet transfers, mobile payments to merchants, and mobile transfers such as remittances.

This has a direct saving to customers who use them to make payments rather than using cash 22 and particularly to banks and others who handle large volumes of cash.

In many developing counties in Africa, Asia and Latin America these savings are being passed on to customers in the form of cheaper financial services, opening up affordable financial services to the poor 23 .

20 Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, July 2012, “Financial Services for the Poor Strategy Overview” http://www.gatesfoundation.org/financialservicesforthepoor/Documents/fsp-strategy-overview.pdf

21 The social cost of cash to society is estimated to be 0.5 per cent to 0.8 per cent of GDP in Europe . McKinsey on Payments, November 2008, http://www.mckinsey.com/App_Media/Reports/Financial_Services/ATMs_War_on_cash.pdf

22 Sukhwinder Arora, Alan Roe and Robert Stone, June 2012 “Assessing value for money: The Case of Donor

Support to FSD Kenya”, Oxford Policy Management

23 Enhancing Financial Sector Surveillance in Low Income Countries, IMF Case Study Paper, April 2012.

Available at: http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2012/041612b.pdf Case Study One: Financial

Innovation in Kenya: The M-Pesa experience.

14

57. Table 2 compares the costs of different banking services in South Africa.

Transactions via WIZZIT, a branchless bank offering mobile payments and transfers 24 , costs consumers 25 per cent less than the cheapest alternative service, the Mzansi basic transaction bank account. This saving represents 0.7 per cent of customers annual income 25 .

Table 2: Comparing the Costs of Innovative and Traditional Distribution Channels

US$

Bank fees per month

Air time fees per month

Transport to bank per month

Total monthly cost

Annualized cost

Annual cost as days of income

Annual cost as a per centage of annual income

Source: Adapted from Ivatury and Pickens (2006)

WIZZIT Mzansi Full service account

5 6 7

0.3

1

6

70

7.5

2.10%

0

1

8

94

10

2.80%

0

1

9

103

11

3.10%

58. A recent study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Mbiti and

Weil (2011), 26 uses two waves of data to examine how M-Pesa is used and its economic impacts. It finds that increased use of M-Pesa lowers the propensity of people to use informal insecure savings mechanisms, and raises the probability of using banks. Evaluated at the mean adoption rate of 40 per cent, M-Pesa has increased the proportion banked by almost 11 per centage points, which represents a 58 per cent increase over the 2006 banking level.

59. M-Pesa operator Safaricom and Equity Bank have now introduced the M-Kesho bank account which allows for mobile phone access to a low-cost bank account.

There is no charge for opening the account, no periodic fees, and no minimum or maximum balance, and interest of up to 3% per year is paid on balances. M-Kesho also offers microcredit and insurance services. Loans are approved or rejected based on a credit score determined by looking at M-Pesa, M-Kesho, and Equity

Bank account activity in the last 6 months, and must be paid back within 30 days.

This supports the theory that electronic payments systems offer a platform for providing new and lower-cost financial products and services.

60. Mbiti and Weil (2011) 27 also note that 25 per cent of M-Pesa subscribers use the service as a savings device. This is supported by qualitative evidence 28 and Kenya’s

24 As well as access to a debit card and ATM cash withdrawals, and the ability to make deposits at branches of two large banks.

25 Ivatury, Gautam, and Mark Pickens, 2006, “Mobile Phone Banking and Low Income Customers, Evidence from South Africa”, Washington DC, CGAP http://www.globalproblems-globalsolutionsfiles.org/unf_website/PDF/mobile_phone_bank_low_income_customers.pdf

26 Isaac Mbiti and David N. Weil, June 2011, Mobile Banking: The Impact of M-Pesa in Kenya, NBER Working

Paper 17129. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17129

27 Isaac Mbiti and David N. Weil, June 2011, Mobile Banking: The Impact of M-Pesa in Kenya, NBER Working

Paper 17129. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17129

15

equivalent of the EFInA Access to Financial Services Survey, FinAccess 2009. Jack and Suri (2011) 29 find that the growth of M-Pesa in Kenya has increased both the share of savings held in the M-Pesa system as well as total savings of M-Pesa users, although the study finds little evidence that people use their M-Pesa accounts as a place to save “usefully large sums”.

61. Agent banking plays an important role in increasing accessibility of financial services and is a complement to mobile transfers

– agents provide the cashier service which allows the recipient to ‘cash in’ the value transferred. Evidence from

Brazil shows how enabling regulation of ‘correspondent’ or agent banking was the critical factor in more than 100,000 retail outlets to becoming agents since 1999, reaching 13 million previously unbanked people.

30

Box 2: The role of agent networks in promoting financial inclusion

The use of non-bank agents in the form of retail shops and other outlets for banking transactions is today regarded as a key component of increasing access to financial services. This is because the cost to a bank of deploying and managing an agent is substantially lower than setting up a branch.

These lower capital and operating costs can result in wider deployment of agents at less risk to the bank and also at lower costs, in fees and travel time, to the customer.

Agents can also remain open when branches are not, making it more convenient for working customers. By removing barriers of distance and inconvenience, agents enable previously excluded customers to access and use the formal banking system, especially when these agents are located within regions previously not being served.

Brazil was one of the early countries explicitly allowing and encouraging the usage of bank agents, known as correspondents, through a series of regulatory changes from the late 1990s. Today, because of its widespread network of agents numbering in excess of 160,000 (104.5 agents per 100,000 adults), Brazil can claim that there is at least one point of financial access in every municipality in the country. For Nigeria to achieve an equivalent target would require more than 100,000 agents.

62. A World Bank evaluation of the impact of a new model of banking introduced in 2002 in Mexico

– a new bank simultaneously opening branches within 800 retail stores and targeting low income customers – uses two waves of the Mexican employment survey and a difference-in-difference methodology to examine the effects of providing financial services to low-income individuals on entrepreneurial activity, employment, and income. The results show that the opening of the bank led to an increase in the number of informal business owners by 7.6 per cent. Total employment also increased, by 1.4 per cent, and average income went up by about

7 per cent 31 .

63. Using banking services and formal savings products appears to increase incomes.

Using secure means of storing value (e.g. mobile money accounts or formal banking) rather than ‘under the mattress’ or in informal community based saving schemes, the risk of loss is reduced and savings buffers become a more

28 Olga Morawczynski and Mark Pickens, 2009, “Poor People Using Mobile Financial Services: Observations on

Customer Usage and Impact from M-PESA” CGAP

29 Jack, William and Tavneet Suri (2011) "Mobile Money: The Economics of M-Pesa" NBER Working Paper 16721

30 Lyman, T., Porteous, D. and Pickens, M. (2008) “Regulating transformational branchless banking: mobile phones and other technology to increase access to finance”. Focus Note No. 43. Washington, D.C.: CGAP.

31

Miriam Bruhn and Inessa Love, June 2009, “The Economic Impact of Banking the Unbanked - Evidence from

Mexico”, The World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 4981,

16

reliable source of managing income fluctuation and shocks 32 .

64. The recent systematic review by the Harvard Kennedy School examined the impact of access to financial services on investment, asset accumulation, consumption, poverty and welfare. It found “compelling evidence that poor people's access to formal banking services can raise their incomes”.

33 Access to savings products increases income by allowing poor households to accumulate assets. Access to credit is associated with higher agricultural incomes and increased and/or smoother consumption for rural farming populations. Improving banking technology was also shown to increase income by allowing households to smooth consumption and accumulate savings.

65. A longitudinal impact study of microfinance programmes conducted by the Small

Industries Bank of India showed that 75% of clients increased incomes by 69%, compared to 31% for the control group; 33% of clients repaid debt and diversified economic activities; while 60% cited an improved social status.

34

66. Savings accounts offered to micro-entrepreneurs in Western Kenya as part of a randomised control trial resulted in strong take-up and usage despite not paying interest. Positive effects were found on savings, business investment and household expenditures (a proxy for income) within 6 months. Among users of the savings account expenditures increased by 32% and across the whole sample expenditures increased by 13%. 35

67. A randomised field experiment in the Philippines on the effects of a deposit collection service and commitment savings product found that both the product and its marketing positively affect household assets and income.

36 The two savings products had similar midterm effects, both increasing savings in the 10-15 month range by $8 to $12 US. While the there is no information on the long-term effects of savings collection, it seems that the initial gains in the magnitude of savings caused by the commitment savings product tapered off in the long term.

68. What about credit? Although use of banking and savings products will address some of the barriers to accessing credit, such as evidence of a financial history, this review found no evidence on whether opening up affordable financial services increases poor people’s access to credit.

Evidence on whether access to credit leads to investment in income generating activity is mixed

37

. In Nigeria, of those reporting that they have taken out a loan, 33 per cent cite their reason as ‘start/expand a business’, and

32 32 Sukhwinder Arora, Alan Roe and Robert Stone, June 2012 “Assessing value for money: The Case of Donor

Support to FSD Kenya”, Oxford Policy Management

33 Pande, Cole, Sivasankaran, Bastian and Durlacher; (2011) “Does Poor People’s Access to Formal Banking

Services Raise their Incomes?” , Harvard University

34 Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) 2008 “Assessing the Development Impact of Micro

Finance Programmes”,(EDRM Number: 2746038)

35 Dupas P, Robinson, J (2007) “Savings Accounts for Village Micro-Entrepreneurs in Kenya”, The Abdul Latif

Jameel Poverty Action Lab, MIT

36 Ashraf, Nava, Dean S. Karlan and Wesley Yin. (2005) “Tying Odysseus to the Mast: Evidence from a

Commitment Savings Product in the Philippines.” Economic Growth Center, Yale University, NewHaven, CT.

37 Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., and Kinnan, C. (June 2012) The miracle of microfinance? Evidence from a randomized evaluation

Available at: http://www.povertyactionlab.org/evaluation/measuring-impact-microfinance-hyderabad-india

17

27 per cent cite

‘buy food/clothes’ 38 .

69. Where loans are used for income-generating purposes, the effect on income can be large. A randomized trial in Kenya showed that access to basic lending bank accounts for the female owners of small businesses resulted in marked increases in business investment relative to the control group, with the ‘ most conservative estimate’ of the effect ‘a 38-56 per cent increase in average daily investment for market women after 4-

6 months’ 39

. Positive effects were found for daily expenditures (a proxy for income) too, which increased by around 37 per cent over the same period.

70. Mobile Payments lead to cheaper, more and larger remittances. Reducing the cost of remittances has been a major contribution of mobile payment and transfer services such as M-Pesa 40 . Gibson et al (2005) find that when remittance fees go down, remittance values go up, and by more than the cost saving to the remitter 41 .

71.

There is significant scope for reducing remittance costs within and to Nigeria. In Kenya, mobile transfers are used for sixty per cent of remittances, but in Nigeria, where mobile payments are nascent, they are used for less than one per cent of remittances and most transfers are made to bank accounts

42

.

72. Remittances help households deal with shocks and crises. Jack and Suri (2010) report that negative income shocks did not significantly impact on changes in household consumption for M-Pesa users, while they did for others, suggesting that

M-Pesa usage helps to smooth consumption. A negative income shock caused nonusers to experience a 7 per cent reduction in household income, while M-Pesa seemed to be able to smooth income seamlessly. This is the equivalent of 3 per cent reduction in income on average across all households. The authors note that some of the resilience, or ability to manage shocks, is likely to be due in part to better education or higher income levels, M-

Pesa is concluded to be a ‘significant source of riskspreading’.

43

73. Remittances appear to help households take advantage of wealth creating opportunities.

A household survey for the World Bank found that 57 per cent of households in Nigeria who received remittances from OECD countries used these resources for ‘…productive investments in land, housing, businesses, farm

38 EFInA Access to Financial Services in Nigeria 2010 Survey

39 Dupas, P., and Robinson, J (2012) Savings Constraints and Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a

Field Experiment in Kenya. JPAL, available at: http://www.povertyactionlab.org/fr/evaluation/savingsaccounts-village-micro-entrepreneurs-kenya

40 Jack, William and Tavneet Suri (2011) "Mobile Money: The Economics of M-Pesa" NBER

Working Paper 16721

41 Gibson, J., McKenzie, D., J., and Rohorua, H. (2005) How Cost-elastic are Remittances? Estimates from

Tongan Migrants in New Zealand. Available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DEC/Resources/PEBGibsonMcKenzieRohorua.pdf

42 Plaza, S., Navarrete, M., and Ratha, D. (2011) Migration and Remittances Household Surveys in Sub-Saharan

Africa: Methodological Aspects and Main Findings. World Bank. Available at: http://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/402/reports

43 Jack, W. and Suri, T (2011) The Adoption and Impact of Mobile Money in Kenya: Results from a Panel

Survey. Presentation to MIT. Available at: http://www.cfsp.org/publications/other/adoption-and-impactmobile-money-kenya-results-panel-survey

18

improvements [and] agricultural equipment.

44 ’ For remittances originating from other

African countries, the per centage remained high at 40 per cent.

74. Financial sector regulation and financial inclusion are complementary.

The IMF notes the importance of building financial stability through regulation (particularly of payment systems and collateral development policies) and acknowledges the role this can play in addressing “…potential sources of instability…”. and encouraging financial market activity 45 . In addition to promoting confidence in the stability of the sector and protection of savings and investments, greater regulation can encourage use of formal mobile banking services 46 .

75. There is a strong body of evidence that deeper financial markets are associated with higher economic growth and some evidence to suggest the deeper markets are a driver of growth 47 . Evidence from Kenya found that broad money growth

– a measure of financial sector depth

– doubled in 2006-2010 compared to 2001-2005.

The increase is attributed to the expansion of banking services, leading to growth in deposits by low-income segments. This gave rise to credit growth of 20 per cent a year by 2010.

48

D. What is the likely impact (positive and negative) on climate change and environment for each feasible option?

1

2

3

Option Climate change and environment risks and impacts, Category (A, B,

C, D)

C

C

C

Climate change and environment opportunities, Category (A, B, C, D)

C

C

C

Categorise as A, high potential risk / opportunity; B, medium / manageable potential risk / opportunity; C, low / no risk / opportunity; or D, core contribution to a multilateral organisation.

76. Financial Sector Development in Nigeria impact on climate change and environment is classified as C, low risk and low opportunity.

77. There are potentially negative environmental and climate impacts through increased carbon emission as a result of increased investment, increased incomes and consumption and through low-level environmental degradation as a result of increased investment in natural resource-intensive business activities. However, the

44 Plaza, S., Navarrete, M., and Ratha, D. (2011) Migration and Remittances Household Surveys in Sub-Saharan

Africa: Methodological Aspects and Main Findings. World Bank. Available at: http://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/402/reports

45 Enhancing Financial Sector Surveillance in Low Income Countries, IMF Case Study Paper, April 2012

46 Klein, M., and Meyer, C. (2011) ‘Mobile Banking and Financial Inclusion -The Regulatory Lessons’ http://www.wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2011/05/18/000158349_20110518143

113/Rendered/PDF/WPS5664.pdf

47 For Example, Ross Levine (September 2004) “Finance and Growth: Theory and Evidence” Working Paper

10766 http://www.nber.org/papers/w10766; Beck, Thorsten & Levine, Ross & Loayza, Norman, 2000.

"Finance and the sources of growth," Journal of Financial Economics, Elsevier, vol. 58(1-2), pages 261-300.

48 Guerguil M, McAuliffe C, Davoodi R, Opoku-Afari M &DixitS, (2010) “The East African Community: Taking

Off?” IMF Regional Economic Outlook April 2010

19

cumulative impact in terms of either emissions or degradation is expected to be negligible given the very limited scale of consumption and production among the poor in Nigeria.

78. There are potentially positive impacts by reducing the vulnerability of the poor to the impacts of climate change, variability, weather related events and other economic shocks; and positive environmental impacts by providing alternative, less environmentally damaging options for dealing and coping with economic shocks such as using savings and insurance rather than depleting natural resource assets.

The scale of the potential impact is unknown but likely to be low as increased savings and insurance is not a particular objective of the programme.

79. There is also potentially minimal but positive impacts through substitution from cash and bank branch based transactions, which use resource to produce and transport cash, into electronic and mobile transactions.

E. What are the costs and benefits of each feasible option?

80. In this section of the Business Case, the £2.05 million for ‘bridging funding’ that was approved by the Secretary of State pending submission and approval of this

Business Case have been included in the costs to give a fuller picture of the costs and benefits of the programme extension and scale-up.

81. The total costs of the feasible options considered are:

1.

£24.5 million - Continue support to EFInA but cease technical support

2. £28.5 million - Continue to support EFInA and technical support to the regulators

3.

£00.0 million - Do Nothing (cease both)

82. The estimated cost of EFInA’s five year strategy for 2013 -2017 is £22.5 million in addition to the existing accountable grant commitment for 2012. This will bring the total commitment to EFInA to £29.9 million. The cost and budget estimates are based on past expenditures.

83. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation currently co-fund some of EFInA’s activities, equivalent to 25% of

EFInA’s budget. Their grant agreement ends in 2012 and whilst they intend to continue supporting EFInA 49 they cannot confirm the level of funding at the moment. As a precaution, this Business Case makes provision to cover all the costs.

84. Provision of £4 million is to continue and expand our regulatory support and to be able to respond to other needs and opportunities that arise. This will bring the total commitment to £5.9 million. Placing one IMF expert adviser within the CBN costs approximately £250,000 per year. Last year we supported three advisers.

85. A further £2 million is for DFID Nigeria’s project management, monitoring and

49 Meeting with Salah Goss, Evelyn Stark, Elizabeth Kellison; Bill and Melinda Gate Foundation; 1 November

2012, Lagos; for Bill and Melinda Gate Foundation Financial Services Programme Scoping Mission to Nigeria

20

evaluation, and research costs. The total cost of preferred option 2 for extension and scale up is £28.5 million, bringing the total commitment to £38.17 million.

86. The Do Nothing option would incur some costs for winding down and closing our support to EFInA, but for simplicity the Do Nothing option is assumed to have no costs and no benefits.

87. The benefits of the programme components have been described in the Strategic and Appraisal Cases. The empirical evidence on the benefits of increasing access to finance summarised in Section B above, in not sufficient for a full economic appraisal of the costs and benefits. There is insufficient quantitative evidence:

at the impact level - improved financial resilience and increased incomes - to value these impacts; and

on the different channels through which the outcome of access to finance leads to these impacts.

88. A partial economic appraisal of costs and benefits is given in Annex A. With respect to the theory of change, this partial economic appraisal covers some of the benefits of using financial services for ‘making transaction’, offers a proxy value for the benefit of using formal financial services for ‘managing income and assets’ - increased value of saving - but does not adequately cover the benefit of increased savings buffers for dealing with shocks, and, critically, does not incorporate any benefits resulting from using financial services for ‘investing in wealth creating opportunities’ which may potentially offer the greatest benefits.

89. The appraisal is modelled after the Value for Money Assessment of Financial Sector

Deepening Trust Kenya by Oxford Policy Management. The evidence covers the costs savings of cheaper mobile payment and transfer services used for paying bills and making remittances, and how the use of formal (regulated) savings products reduces the risk of savings being lost or stolen compared to ‘under the mattress’ or in informal community schemes, therefore increasing the value of savings. These benefits are quantified and valued to illustrate that, even considering a limited number of benefits, the benefits of expanding and scaling up the programme are greater than the costs.

90. An important caveat is that, although EFInA’s 2008 and 2010 Access to Finance in

Nigeria Surveys offers some useful data on the use of formal financial services, the appraisal has required a number of ‘heroic assumptions’ about the increases in the usage of savings products and especially about mobile payment and transfers, which are relatively new in Nigeria. Constructing a realistic counterfactual ‘no EFInA’ scenario has been particularly challenging because very little data is available for the

‘pre EFInA’ period.

91. In view of the data challenges, the appraisal erred on the side of caution in its assumptions

, particularly on the counterfactual ‘no EFInA’ increase in access to financial services, which is assumed to be two thirds of the ‘with EFInA’ increase.

Further the appraisal included sensitivity analysis on:

the counterfactual increase in people with access to finance in the absence of

EFInA (contribution)

the proportion of the benefits accruing to people with access to finance which can be attributed to EFInA rather than other agents (attribution)

21

the period over which the benefits continue (duration).

92. A further challenge to providing a full economic appraisal of the options has been appraising the benefits of the technical support to regulators, given the complementarity of the outcomes and the huge assumption about attribution and contribution which would be required. The approach adopted is to appraise the total programme extension costs (Option 2) and the quantifiable benefits of increased access to finance.

93. The appraisal methodology, findings and sensitivity analysis are presented in Annex

A.

94. The summary table below shows that even with a partial analysis of the benefits and the model scenario’s reasonably cautious assumptions about the duration of the benefits and the attribution of the benefits to EFInA, the programme extension and scale up has a net present value (NPV) of £37.6 million pounds.

95. Recognising that other appraisals may have had access to better data and make different assumptions, including about which costs are included, this NPV appears to be as good or better than other Access to Finance programmes such as the Skills and Innovation for MicroBanking in Africa Programme and the Uganda Financial

Services Inclusion Programme, but not as good as the Kenya Access to Finance for

Development programme; and as good or better than two other recent DFID Nigeria programmes: State Partnership for Accountability, Responsiveness and Capability

(SPARC) scale up and Child Development Grants.

96. Even under the most pessimistic assumptions the preferred option for the programme extension has a positive net present value of £0.4 million pounds, i.e. the discounted benefits just exceed the discounted costs.

Table 3: Net Present Value of Financial Sector Development Extension Optio n 2, £, million

Model scenario: 5 years of benefits beyond intervention, attribution profile A

Programme

Costs

28.5

Discounted

Costs

21.6

Discounted

Benefits

59.2

NPV

37.6

Cautious scenario: no benefits beyond intervention, attribution profile A

More cautious scenario: no benefits beyond intervention, attribution profile B

28.5

28.5

21.6

21.6

31.8

22.0

10.2

0.4

Optimistic scenario: 15 years of benefit beyond intervention, attribution profile A

28.5 21.6 80.9

Notes: Assumes DFID Nigeria’s standard 10% discount rate

Attribution of benefits to EFInA are:

Profile A: 50% remittances, 10% savings and 50% mobile money

Profile B: 25% remittances, 10% savings and 50% mobile money

The attribution profile of the benefit stream is lowered beyond the intervention period. See annex A detail.

F. What measures can be used to assess Value for Money for the intervention?

59.3

22

97. The recent Annual Review developed unit cost value for money indicators for both of the programme components. These are presented in Table 4 below for the programme lifetime and the programme extension timeframes and budgets.

Table 4: Unit Cost Indicators for EFInA and Technical Support to Regulators

Component

EFInA

Programme

Total

EFInA

Programme

Extension

Time frame

2008-

2017

Total Costs, £

29,900,000

Nature of Benefit

Additional people with access to finance

Units of Benefit

12,000,000

Cost per

Unit of

Benefit, £

2.49

Technical

Support

Programme

Total

2013-

2017

2008-

2017

22,500,000

5,900,000

Additional people with access to finance

Loss GDP loss avoided through prevention of major financial crisis, 60% of GDP

Loss of GDP avoided through effective management of a financial crisis, 5% of GDP

7,700,000

£871,200,000

£72,600,000

2.92

Technical

Support

Programme

Extension

Loss GDP loss avoided through prevention of major financial crisis, 60% of GDP

Loss of GDP avoided through effective

£871,200,000 0.01

2013-

2017 4,000,000 management of a financial crisis, 5% of GDP £72,600,000

Source: DFID Nigeria estimates based on EFInA Annual Review 2012, Report prepared for DFID

0.06

Nigeria by Hennie Bester, April 2012

0.01

0.08

98. Assessing the value for money offered by the placement of expert advisers to the

CBN and other regulatory support requires some ‘heroic assumptions’ particularly on the attribution of the benefits. The annual review developed a methodology for estimating t he economic benefit of ‘lost GDP avoided’ per pound spent with 1 per cent of the benefit attributed to DFID’s technical support. This has been adapted in

Table 4 above to show a cost per pound of benefit 50 . Either of these indicators could be used to assess the value for money of regulatory support. Cost per pound of economic benefit has the advantage of being comparable to other unit costs.

99. The Annual Review found estimated the value for money of technical support to regulators to be between £68 (at a 5% impact on GDP) and £818 (at a 60% impact on GDP) per pound spent 51 . It concludes that “this represents extremely good value

50 The Annual Review estimates a “benefit per £1 spent”, whereas the Table of Costs and Benefits estimates the “£ cost per benefit”.

51 This calculation does not take into account the time factor. Cecchetti’s research, referred to above, found that serious financial crises occur every 20 – 25 years.

23

for money. It would still be good value for money if the contributions of the experts are assumed to be substantially less than 1 per cent ”.

100. For EFInA a range of indicators are used to assess its cost effectiveness in reaching beneficiaries both at the outcome and output levels, the efficiency with which it turns inputs into outputs, and the economy of its inputs:

Outcome level: unit cost per additional person with access to finance

Output level: unit cost per beneficiary of EFInA grant funded projects

Efficiency: to be determined

Economy: administration costs as a per centage of total costs

G. Summary Value for Money Statement for the preferred option

101. The value for money EFInA offers can clearly be seen in the cost effectiveness of its contribution to increasing access to financial services in Nigeria at a cost per beneficiary over the programme lifetime of £2.49. This is substantially better than other Financial

Sector Deepening Trusts and Programmes (which do not benefit from such economies of scale) shown in the Table 5 below.

102. The Annual Review also considered the cost effectiveness of EFInA’s outputs and the economy of its operations to date:

The cost per beneficiary of two EFInA grants to pilot new financial products were calculated at £5.45 (mobile payments) and £10.90 (agent banking).

The outputs were achieved with a very limited staff complement, significantly less than other Financial Sector Deepening Trusts.

“Overall EFInA has delivered remarkable value for money.”

103. In terms of economy, EFInA’s administration costs as a per centage of total costs have averaged 30 per cent to date. This is anticipated to fall to 27 per cent for 2012-2017.

Table 5: Comparing Financial Sector Development Programmes

Nigeria

Enhancing

Kenya

Access to

Tanzania

Financial

Key Characteristics

Financial

Innovation and Access

Finance for

Development

Sector

Deepening

Trust

Population (mil) 162.5 41.6 46.2

Rwanda

Access to

Finance

Uganda

Financial

Services

Inclusion

Programme

34.5

GDP per capita (US$)

% of population <$1.25 (PPP)

% Population without access to finance

1452.1

64.4

46.30%

808

19.7

40.00%

528.6

67.9

56.00%

10.9

582.8

76.8

52.00%

487.1

28.7

28.00%

Target increase in access to finance 12,000,000

DFID Programme Budget (£) 29,900,000

3,606,720

16,000,000

1,544,004

19,540,000

510,911

10,000,000

4,000,000

17,030,000

Cost per beneficiary (£) 2.49 4.44 12.66 19.57 4.26

Timeframe 2008-2017 2011-2015 2007-2015 2009-2013 2012-2017

Data taken from Access to Financial Services Surveys and Programme Documentation such as Strategies and Business Cases. In some cases the target increase in access to finance has been extrapolated from a per centage increase. Therefore the cost per beneficiary figures are rough estimates.

24

3. Commercial Case

Indirect Procurement

A. Why is the proposed funding mechanism/form of arrangement the right one for this intervention, with this development partner?

104. DFID issued an accountable grant to EFinA in December 2008.This was the right approach because EFinA is a not-for profit organisation, limited by guarantee. It is run by a Chief Executive Officer and a Board of Directors. EFinA has also received 23% of its grant funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

105. An extension of the grant is preferable to the alternative now of seeking competitive interest in setting up a new means of providing financial inclusion and access. This is firstly due to the considerable success and achievements of the programme. This justifies a continued relationship. Secondly, the project was carefully set up as a newly formed, independent local organisation, with its own managerial and operational setup and its own ‘Nigerian’ identify. This has worked well, in particular in influencing

Nigerian institutions like the CBN or Nigerian banks.

106. Thirdly, an extension of the grant is judged to be significantly preferable to seeking competitive interest now in managing EFInA. A change of management arrangements would inevitably incur considerable cost and delay through a fresh start. Moreover, the reality is that unless it were common knowledge within the relevant market that

EFinA’s performance was below par, few if any other potential service providers would judge the cost of bidding to be worth it, recognising that DFID is unlikely to make a change at this juncture in the life of the project.

107. The funding mechanism used to date for providing technical support to regulators is a

Trust Fund with the International Monetary Fund, which identifies, places and manages long term advisers to work in the CBN and other regulators. The IMF is well placed to identify and manage such highly specialist expertise and this approach allows for complementarity with other IMF activities and programmes. In the future we may supplement this form of support with other directly procured support such as short term consultancies as needs arise.

B. Value for money through procurement

108. The case rests partly on the three factors outlined above. In addition, the project has achieved excellent value for money, through its programme management arrangements and the efficiencies it has achieved, which were particularly commended in the annual review and are discussed above.

109. Although EFInA is a grant awarded without competition, EFInA uses open international competition to award research contracts, and innovation fund grant applications are carefully scrutinised by a panel, including DFID and Bill and Melinda

Gates Foundation representatives, to ensure that they represent best potential value.

Applications are received in response to targeted Request for Proposals and are

25

evaluated according to specified criteria covering: innovation, viable project idea, developmental impact, capacity to implement, and consumer protection and financial education.

110. The management and cost regimes of the project are impressive, enabling high proportion of the budget to be incurred directly on the programme rather than its management. Management costs are spread between salaries, direct overhead costs relating to the provision of staff and brought-in consultancy (e.g. medical insurance, visas, etc.), indirect overhead costs to contribute to the costs of being in business, such as corporate operations, managed costs, recruitment, back office administration, headquarters, etc. This represents £6m of the £22.5m increase, which appears acceptable at face value. We will discuss with EFInA the make-up of the cost to ensure that waste and cost has been minimised.

111. Payments from DFID are made quarterly in advance, on request, against certified statements of actual expenditure incurred during the previous quarter. Although the most recent annual review identified no audit concerns, we will conduct fresh due diligence checks on EFinA in view of the size of the increased investment.

4. Financial Case

A. What are the costs, how are they profiled and how will you ensure accurate forecasting?

112. The costs for the extension and scale-up of the Financial Sector Development (FSD) programme for the period 1 April 2013 to 31 December 2017 are £26.45 million.

113. On the 16 November 2012 t he Secretary of State approved ‘bridging funding’ of £2.05 million for six months from 1 October 2012 to 31 March 2013, pending submission and approval of a Business Case for extending and scaling-up the programme from 1

January 2013 to 31 December 2017. T he ‘bridging funding’ covers cover a shortfall in budget to 31 December 2012 and the programme scale-up costs for 1 January to 31

March 2013. The costs for the rest of the five year extension period are

£26.45 million.

114. The programme extension and scale-up costs will cover the Accountable Grant to

EFInA and Technical Support to Regulators; as well as project management (PM), monitoring and evaluation (M&E) and research managed directly by DFID. Table 4.1 gives the approximate breakdown of these extension costs by project component,