Pressure Ulcer Prevention Revisited

advertisement

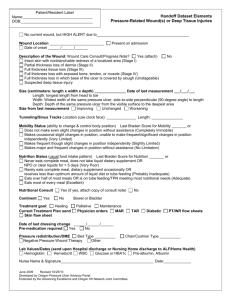

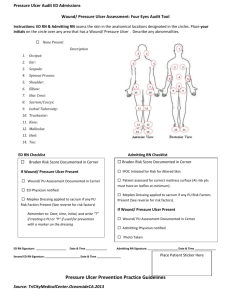

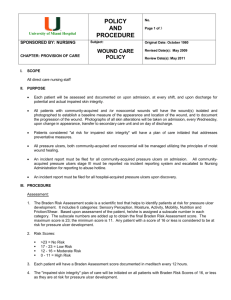

Pressure Ulcer Prevention Revisited Linda J. Cowan, PhD, ARNP, FNP-BC, CWS Research Health Scientist North Florida / South Georgia Veterans Health System Gainesville, FL Clinical Associate Professor, University of Florida College of Nursing Financial Disclosures • Research Funding Received: – VA Office of Nursing Services – VA QUERI – Biomonde – HealthPoint/Smith & Nephew – Celleration, Medline, Hollister Clinical Problem • Pressure ulcer prevention (PUP) is used as a quality of care indicator and is a top priority for all health care facilities. • Preventable pressure ulcers still occur – PUs impact 1.6 million Americans each year, collectively costing $3.6 billion annually in the United States (US) (Baranowski, 2006). Objectives • Describe important evidence from PUP research • Identify at least 3 components of successful PUP programs • List essential members of PUP teams • Describe methods of PUP education that providers may be more inclined to complete Key Questions to Answer • • • • • • How is your facility doing? Who should be involved? Where do we start with PUP strategies? Do providers want more PUP education? How should this education be delivered? Does recent research or the scientific literature have anything to contribute to PUP efforts? • What are some helpful tips to making a successful PUP program? PUP Efforts: HOW IS YOUR FACILITY DOING? Our Organization: Veterans Health Administration (VHA) • • • • America’s largest integrated health care system Over 1,700 sites of care Serves over 8.3 million Veterans each year Aspirational goal for pressure ulcer reduction set by VHA: “Getting to zero” • Target preventing all avoidable pressure ulcers particularly most severe (stage III & stage IV) • Office of Inspector General (OIG) completed 42 site visits of VA facilities (July 2013 to April 2014) to evaluate implementation of VHA Handbook 1180.02 “Prevention of Pressure Ulcers” revised July 1, 2011 OIG: Top 7 areas for VA improvement 1. Consistent documentation of PU location, stage, risk scale score, and date acquired. (Facilities need the most improvement in this area) 2. Facility-defined requirements for patient & caregiver PU education (for those at risk or w/PU); staff documentation of how/when this was provided 3. Required activities performed (and documented) for patients determined to be at risk for pressure ulcers and for patients with pressure ulcers 4. Facility defined requirements for staff pressure ulcer education, and acute care staff received training on how to administer the pressure ulcer risk scale, conduct the complete skin assessment, & accurately document findings. 5. Skin inspections & risk scales performed: transfer, change in condition, & D/C 6. If the patient’s PU was not healed at discharge, a wound care follow-up plan was documented, and patient was provided appropriate dressing supplies. 7. For patients at risk for and with PUs, interprofessional treatment plans were developed, interventions were recommended, and Electronic Health Record (EHR) documentation reflected that interventions were provided. PUP Efforts in VA Facilities • OIG: two areas needing most attention: – Education (24 findings) – Documentation (28 findings) – These two areas accounted for 35% of all negative site visit findings VA Wound Provider Survey 2014 • National VA Survey: – March 3rd to March 31st, 2014 – online, anonymous – 1,726 VA wound providers • ~24% response rate • Purpose: – gather current evidence about experiences, education, preferences, and opinions of wound care providers related to wound management and PUP Cowan, L & Garvan, C. (2014). Online Survey of VA Wound Providers. Poster presentation at SERWOCN, August 27, 2014, Montgomery, AL. Characteristics of Respondents and their facilities Main role (n=303 respondents) RN Wound Consultant ARNP MD PT DPM Other (OT, CWOCN, SW, PharmD, etc.) Main clinical setting (n=302) Inpatient acute care (not intensive care) Inpatient acute care (intensive care) Outpatient care Rehabilitation care Long term care Spinal cord injury care Other N % 98 77 49 31 16 13 19 32% 25% 16% 10% 5% 4% 6% 53 41 107 8 35 54 4 18% 14% 35% 3% 12% 18% 1% Cowan, L & Garvan, C. (2014). Online Survey of VA Wound Providers. Poster presentation at SERWOCN, August 27, 2014, Montgomery, AL. Board certification (n=303) N % Currently board certified (wound) Was (wound) board certified in the past Never (wound) board certified 157 8 138 52% 3% 46% (SCI Providers: 12 BC / 0 BC in past / 38 never BC) Nature of wound management training (n=303) None Only informal Some formal Years’ experience in wound care field (n = 271) 7 2% 98 32% 198 65% Mean = 14.2 SD = 9.8 Cowan, L & Garvan, C. (2014). Online Survey of VA Wound Providers. Poster presentation at SERWOCN, August 27, 2014, Montgomery, AL. VA Wound Provider Survey 2014 Active inter-professional skin or PUP task force at your facility? (n=303) Yes No Not sure SCI Setting Yes No Not sure N % 229 31 28 80% 11% 8% 67% 2% 10% Cowan, L & Garvan, C. (2014). Online Survey of VA Wound Providers. Poster presentation at SERWOCN, August 27, 2014, Montgomery, AL. PUP Efforts: WHO SHOULD BE INVOLVED? TEAM: Together Everyone Aims for More Interprofessional Approaches to Pressure Ulcer Prevention (PUP) VeHU Presentation September 18, 2014 Charlene Demers, ARNP, CWOCN Aimée D. Garcia, MD, CWS, FACCWS Team “ A number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance goals, and approach for which they are mutually accountable.” Katzenbach J & Smith D. 1993. The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-performance Organization. Harvard Business School Press. Teams for PUP Pressure ulcer assessment, prevention, and monitoring are an interprofessional (not solely WOC nurse) responsibility that includes: – Systematic application of risk assessment – Implementation of preventive and therapeutic measures – Monitoring outcomes – Education – Documentation Team members • • • • • • • • • Physicians- Surgeon and Medicine (PAs) Nursing (NP, RN, LPN, CNA) Physical Therapy (PT, PTA) Occupational Therapy Nutrition Pharmacy Prosthetics Social worker(s) / Case Managers Administration Interprofessional Approach • Physicians – – – – Early surgical intervention to improve mobility Ordering of pressure redistribution surface after surgery Supervision of overall clinical care Collaborate in prevention plan • Nursing – Nursing assumes the primary role by identifying those at risk, initiating and coordinating the plan of care for prevention – Risk assessment and prevention strategies • Implementation of standing order sets – Turning and repositioning / Offloading – Identifying and entering necessary consults • PT/OT, dietician, social worker, etc. • Rehabilitative and/or SCI staff – recommend strategies to improve mobility and use of protective & pressure redistributing devices • Physical Therapy – improve mobility, function and activity levels – Evaluate safety of ambulation – Ordering appropriate durable medical equipment to improve patient’s functional status • Occupational Therapy – Seating evaluations • Pharmacists – assist with analysis of medication profile, product availability, and parenteral nutrition formulation • Social Workers – assure prevention is priority across continuum of care – evaluate and address special needs and discharge planning • Informatics – facilitate documentation and accurate communication among team • Quality Management – assists with monitoring incidence and evaluating program outcomes • Education Department – assists with ongoing education for staff and patients and/or the patient’s designated family members, surrogates, or authorized decision makers • Logistics and Prosthetics – assist with availability of products and devices for prevention PUP Efforts: WHERE DO HEALTH CARE FACILITIES START WITH PUP STRATEGIES? Start with ABCDE… • ABCDEs of PUP Initiatives (Lyder & Ayello, 2009). – Administrative support backed by support at patient care level is vital – Bundling care practices + having an identifiable theme – Creating culture of change, commitment, and communication – Documentation of pressure ulcer prevention practices must be visible – Education is essential (I would also add: all initiatived should be Evidence-based) Administrative Support • Top – Down approach (National, Regional, Facility) – Create positive culture, support staff, provide accurate & consistent policies and tools (outcome tracking & reporting) • Ways to approach Administration – Focus on Improving Quality and Cost Savings • Demonstrate how efforts (investment of people, resources, time) will improve delivery of safe & effective patient care & patient outcomes • Numbers talk: Know your potential ROI (Return on Investment) – Conference, Workgroup, Lean Project, Systems Redesign • PU prevention and management must be identified as priority with resources allocated to develop & sustain effective program • Support for interprofessional approaches • Support for certified wound specialists & their continuing education (CWOCN, CWCN, CWS, WCC, etc.) • Support for equipment & devices such as OR table pads, specialty beds, mattresses & seat cushions, heel floatation devices, etc. Bundling Practices • Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) evidence-based best practices (EBBP) for pressure ulcer prevention in “Toolkit for Improving Quality of Care” (2011) – “Bundle” concept was developed by Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) – Concept of skin care “bundle” • Groups together specific care practices to achieve desired outcome – Three critical components (evidence-based): • Standardize pressure ulcer risk assessment • Comprehensive skin assessment • Care planning and implementation to address areas of risk SKIN Bundles • VA Skin Bundle (VASKIN): a concerted effort to disseminate EBBP into clinical setting(s) • VA SKIN bundle exceeds three critical components – by incorporating specific (evidence-based) interventions based on recommendations published by National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Wound Ostomy, Continence Nurses Society • VA SKIN bundle is evidence-based framework – but will allow for innovation for special population(s) Great Example: VISN16 Success • “VA Skin Bundle” concept approved by 21 subject matter experts from VISN 16 Skin Integrity Workgroup – At VISN 16 Skin Integrity Summit II held September, 2012 in Ridgeland, MS – Additional edits/revisions provided by members of VHA National “HAPU” Prevention Initiative supported by Office of Nursing Services (ONS) • Skin Bundle example in next slide presented nationally on Virtual Learning University (VeHU) in 2013 – Special recognition goes to Suzy Scott-Williams, RN, MSN, CWOCN & Mona Baharestani, PhD, APN, CWON, FACCWS • Over 300 clinicians attended virtually V A Veteran’s Skin Bundle S K I N Select Surfaces and Devices to Redistribute/Relieve Pressure Assess Skin and Risk Status Risk Assessment on Admission (Braden, SCI, Surgery, medical device) Inspect skin (head to toe) during care activities (e.g. turning, bathing) Keep Turning and Repositioning Incontinence Management Nutrition and Hydration Assessment and Intervention Suzy Scott-Williams, RN, MSN, CWOCN, 2013 Using Quality Improvement • Process Improvement / Quality Improvement and Continuous Quality Improvement methods to implement Bundles: – Plan – Do – Check - Act – Lean – Six Sigma – Systems Redesign – VA TAMMCS VA-TAMMCS Framework VISN16 Workgroup Reduce HAPU stage III & IV by 30% from FY12 to FY13 Interprofessional Team, Nurse Managers, Staff Nurses Nursing Process VANOD data, Internal assessment Mini RCA on each incidence Action Plan, Education, compliance, equipment, devices resources Communication plan, feedback, Executive leader involvement Comparison of other Skin Bundles • VHA: VA SKIN – VA: Assess risk & skin, Select surfaces/devices, Keep turning/repositioning, Incontinence management, Nutrition & hydration (assess & address) • AHRQ: AHRQ Pressure Ulcer Bundle – Comprehensive skin assessment, standardized risk assessment, evidence-based care planning & implementation to address areas of risk, defining staff roles, educate staff, clinical pathway • SIGN & Ascension Health: SSKIN – Skin inspection, Surface selection, Keep turning/keep moving, Nutrition • Common to all: Documentation, Education, Evidence Authors: Roger Resar, MD: Senior Fellow, IHI; Assistant Professor of Medicine, Mayo Clinic School of Medicine Frances A. Griffin, RRT, MPA: Faculty, IHI Carol Haraden, PhD: Vice President, IHI Thomas W. Nolan, PhD: Senior Fellow, IHI Berlowitz et al.(2011) AHRQ Acute Care Skin Bundle Build Your Own “Bundle” Risk Assessment Skin Inspection Keep Moving / Repositioning Prevent Shearing Forces Float / Elevate Heels Incontinent Care: Moisture Management Pressure Redistribution: Support Surfaces Patient / Caregiver / Staff Education Perioperative Skin Bundle (Scott-Williams, 2012) Skin Assessment : Pre-op, post-op, recovery, transfer (educate professionals) Scott-Triggers: Tool developed by Suzy Scott-Williams to identify surgical patients needing specific interventions to prevent perioperative PU (>2 = risk) Braden Scale: Common risk assessment tools may not be valid in O.R. setting (score <20 = risk) Transfer Devices: Appropriate transfer devices protects staff from injury and reduces risk of friction and shear injury to patient Table Pads: Pressure reducing/redistributing pads for O.R. tables (recommended for any surgical procedure over __ hours) Positioning Equipment: Stirrups, arm boards, heel devices, ulnar padding (based on evidence); heels should always be off-loaded in supine position. Padding: Use padding and padding practices that are evidence-based Hand-off Communication: Use effective and consistent communication tools/practices SCI Specific Skin Bundle • Kathleen Dunn and Susan Thomason 9-6-2013 – Risk – Assessment – Interventions – Annual Evaluation – Patient Education • Pressure Ulcer Risk Factors (Significant in evidence-based literature) – – – – – • Complete SCI History of at least 1 previous ulcer Pressure Ulcer (PU) Recurrence Number of years since injury Injury duration >30 years… Per VHA Handbook 1180.02 (2011) “Prevention of Pressure Ulcers” – Document risk upon admission, discharge, transfer, or change in condition using Braden, or a pressure ulcer risk scale that has been validated in people with SCI … • Per VHA Handbook 1176.01 (2011) “Spinal Cord Injury/Disorders (SCI/D) System of Care” – All Veterans with impaired sensation or mobility must have an annual comprehensive assessment of risk factors, a review of prevention strategies, a thorough inspection of skin/body wall, and recommendations for pressure ulcer prevention shared with the Veteran (i.e., a pressure ulcer prevention plan)… Bundling care practices is only one part: Don’t Forget the whole ABCDE Approach • Administrative support backed by support at the patient care level is vital • Bundling care practices – have an identifiable “theme” • Creating a culture of change, commitment, and communication • Documentation of pressure ulcer prevention practices must be visible • Education is essential Creating a Culture… • Change – Never easy but necessary for improvement – Embrace the concept of a JUST culture • Avoiding blaming people for failure • Critically examine processes which result in failure • Commitment – Patient Safety First • Communication – Most process failures result from lack of communication – Documentation Documentation of PUP Practices • Must be visible – readily available and easily found (patient’s medical records & unit tracking) • Must be accurate – date, time, patient assessment, skin & wound assessment, patient needs (including education), plan to meet these needs, exactly what was done, and follow up • Must be consistent • “Tending of data on HAPU rates, severity, and documentation compliance must be integrated into the culture of the unit” (Susie Scott-Williams, 2012) Education is Essential • Administration • Clinical staff • All settings – inpatient, outpatient, ICU, LTC, Rehab, home, etc. • Ancillary staff – housekeeping, engineering, volunteers, etc. • Patient • Caregivers / family members • Community All Initiatives should be Evidence-Based Sources of Evidence: • External Evidence – Robust research – Strength of evidence • Quality – Quantity – Validity - Reliability • Internal Evidence – PI/QI methods – Applicable to your situation? Having Evidence Based Protocols Taken from AAWC presentation “Developing a Comprehensive Content Validated Pressure Ulcer Guideline” (2012) on www.aawconline.org - Susan Girolami & Laura Bolton (Co-Chairs). PUP Guidelines AAWC Wound Care Specialty Council • Significant Findings of Mean Content Validity for PU Prevention Guidelines (Sandwich) – – – – Documentation Interdisciplinary Approach Risk Assessment Nutritional Assessment • Hydration & Nutrition plan of care – – – – – – – Medical/surgical history Psychosocial/quality of life Environmental factors (fall risk) Rehabilitation & restorative programs Position to manage pressure, shear, friction Off-loading beds, chairs, OR equipment Physical Exam • Skin inspection & Maintenance – Education PUP Efforts: DO PROVIDERS WANT MORE PUP EDUCATION? IF SO, HOW SHOULD THIS EDUCATION BE DELIVERED? 2014 VA Wound Provider’s Survey Wound education adequate? (n=289) Yes No I don't know 11% 33 PUP education adequate? (n=286) Yes No I don't know 13% 29% 36 83 38% 110 60% 49% 173 140 Almost 50% said NO Which types of wound are you most confident caring for? VERY confident caring for this wound type % respondents 81% See this wound type weekly % respondents 66% Pressure ulcers Moisture related dermatitis and incontinence associated dermatitis 72% 65% 73% 53% Acute wounds Chronic wounds Surgical wounds Venous leg ulcers Traumatic wounds Diabetic foot ulcers Arterial ulcers/Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) 62% 61% 60% 52% 44% 41% 38% 55% 79% 51% 55% 21% 51% 43% Minor injuries (abrasions, skin tears) Top 10 Topics of Interest for Clinical Education 1 2 3 VA Wound Provider’s Survey Current research findings regarding chronic wounds and wound care Identifying and treating unusual wounds 7 New products available for dressings and topical treatments Biological wound therapies (e.g., stem cell, personalized wound treatments, skin substitutes, wound matrices) Infection and reducing bioburden/biofilm Overview of advanced wound therapies (negative pressure, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, electrical stimulation, ultrasound, etc.) How to achieve a multi-disciplinary approach to wound management 8 Legal issues with chronic, non-healing wounds or pressure ulcers 4 5 6 9 Pressure ulcer prevention, treatment or management Vascular issues: Treatment (surgical and non-surgical interventions for 10 venous and/or arterial insufficiency) Cowan, L & Garvan, C. (2014). Online Survey of VA Wound Providers. Poster presentation at SERWOCN, August 27, 2014, Montgomery, AL. Educational Preferences: Setting • Preference of when and where you would like to receive wound management training, CEUs, CMEs, updates or in-services (n=299): – Anything I can do during work hours - having “protected time” to complete it = 86% (n=257) – Anything I can do at home or on my own time = 14% (n=42) Preferred method for receiving training, updates, CEUs, CME, or in-services (n=303) # of respondents Face-to-face trainings or workshops Attending professional conferences Simulation learning in-person Interactive computer modules with case scenarios Self-study online Self-study written materials Online gaming modules where you can play a game while you are learning 245 225 152 133 73 65 51 PUP Efforts: WHAT DOES RECENT RESEARCH EVIDENCE (SCIENTIFIC LITERATURE) CONTRIBUTE TO PUP EFFORTS? Clinical Pearls about Evaluating Research Evidence • Know where to look in articles – Abstract: Research question same as yours? – Methods: Appropriate type of study? Large enough sample? Sampling techniques? Robust methods? Valid tools and outcome measures? – Results: Believable and can be applied to your situation? Looking for Evidence • Evidence Syntheses versus Evidence Summaries • Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews • Decision Support Tools online – Best Practices versus Evidence-Based Guidelines • Evidence-Based Guidelines • Primary Studies • Evidence-based text-books, professional organizations, expert opinion • PI/QI Evidence Tables: • Association for Advancement of Wound Care Guideline Department – Pressure Ulcer Care Initiative – References Updated August 16, 2011. – PU Evidence Table 8.1 derived from 13 PU Guidelines (56 pages): http://aawconline.org/wpcontent/uploads/2011/03/AAWCPressureUlcerGui delineEvidenceTableAug11.pdf – AAWC PU Guidelines: • http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23985608 Example from Evidence Table PUP Research Evidence Fogerty et al. 2008 • Used 2003 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) dataset of 7,977,728 inpatient discharges. – Included 37 states (representing 90.3% of US population) – 944 hospitals • Total sample with PU was 94,758; without PU was 6,610,787 • Identified top 45 risk factors in acute care which included 25 medical diagnoses – at top of list: Age >75, race, paralysis, infection/sepsis, and nutritional deficiency (see next slide for top 11 diagnoses) – majority of risk factors identified were not accounted for by Braden Scale Fogerty M, Abumrad N, Nanney L, Arbogast P, Poulose B, Barbul A. (2008). Risk factors for pressure ulcers in acute care hospitals. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 16: 11-18. Fogerty et al. Risk factors 1. Age > 75 years OR 12.63* *(as AA age, risk goes higher than Cauc as they age) 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Gangrene diagnosis OR 10.94 (95% CI 10.43, 11.48) Paralysis OR 10.3 (95%CI 9.69, 10.69) Septicemia OR 9.78 (95%CI 9.33, 10.26) Osteomyelitis OR 9.38 (95% CI 8.81, 9.99) Malnutrition OR 9.18 (95% CI 8.81, 9.99) Pneumonitis/Pneumonia OR 8.7 (95% CI 8.33, 9.09) UTI OR 7.17 (95% CI 6.96, 7.38) Bacterial infection OR 5.71 (95% CI 5.49, 5.93) Senility OR 4.84 (95% CI 4.62, 5.07) Mycoses OR 4.47 (95% CI 4.41, 4.86) PUP Research Evidence • Cowan et al. 2012 – Veteran Sample – Sample of 213 Veterans. Compared Braden Risk Score to other Medical factors; found 2 Braden sub-scores more predictive of PU than total scores; 4 medical factors (pneumonia, surgery, candidiasis, malnutrition) more predictive than Braden total scores • Niederhauser et al. 2012 – Systematic Review of 12 studies – Comprehensive PUP programs can be effective but sites need to rigorously evaluate their programs and publish their results • Sullivan & Schoelles 2013 – Systematic Review of 26 implementation studies – Key components, “simplification & standardization of PUP interventions & documentation; interdisciplinary teams, leadership, designated skin champions, ongoing staff education, sustained audit & feedback” • Soban et al. 2011 – Systematic Review of nurse-focused QI interventions – SR of 39 studies: Interventions combined with educational and/or QI strategies are effective at reducing PU incidence: assembling a team, performance monitoring and FEEDBACK are very important • Falise et al. 2014 PHHP Honor’s Thesis (in press) – Looked at nutrition; ADL impairment; relationship between BMI and PU using MDS 3.0 dataset: ADL impairment more predictive than BMI, but very low BMI (undernourished) strongly associated with PU Pieper & Kirsner 2013 Pieper, B. & Kirsner, R. (2013). Pressure Ulcers: Even the Grading of Facilities Fails. Ann Internal Med. 159(8): 571-572. • Estimate 7.5 million persons annually w/PU (worldwide) • Problems with PU data and research evidence: – Coders interpretations of documentation in medical record – Terminology about PU is confusing: PU, pressure sore, decubiti, decubitus, decub, bedsore, etc. – Correct identification of PU pics by expert clinicians was only 57%, with lowest scores for identification of stages III and IV, suspected deep-tissue injury, and unstageable ulcers – Levine and colleagues report mean total PU knowledge score of 69% for physicians, PU knowledge score of nurses was 79%. – Lowest scores were in knowledge of risk factors. Risk Assessment Pancorbo-Hidalgo, P (2006). Risk assessment scales for pressure ulcer prevention: a systematic review (Meta Analysis), Journal of Advanced Nursing 54(1), 94–110. (Cited by 278 journals) – 14 databases, 1966-2003, 49179 33 studies met criteria Table 5 Accumulated analysis of indicators of validity *Weighted average. Scale n studies Sensitivity Specificity PPV(%)* (%)* (%)* NPV(%)* Efficacy (%)* 20 N total Patients 6443 Braden (1987) US Norton (1962) UK Waterlow (1985) UK Clinical Judgment 57.1 67.5 22.9 91.0 66.7 5 2008 46.8 61.8 18.4 87.0 60.2 6 2246 82.4 27.4 16.0 89.0 34.4 3 302 50.6 60.1 32.9 75.9 58.0 Pancorbo-Hidalgo Conclusions • Lack of evidence that use of risk assessment scales decreases pressure ulcer incidence • Braden Scale has best validity and reliability indicators, and has been used in a large number of studies in a wide variety of settings (though application across settings should be validated) • Braden and Norton Scales predict pressure ulcer development risk better than nurses’ clinical judgement • Waterlow Scale has good sensitivity but low specificity Take home message: Something is better than nothing Other Difficulties with PUP Documentation and Research Evidence • Cowan et al. 2012 – Veteran Sample – Key diagnoses not added to diagnosis list or active problem list; inconsistent Braden scores from one day to next (and sometimes one nurse to the next during same 24 hours); key risk factors and PUP interventions not documented; inaccurate Braden scores and PU identification (staging) • Niederhauser et al. 2012 – Systematic Review – Only 15% older adults at risk for PU had supportive device doc by day 3 – Study of 2,425 MCR pts in acute care: only 23% of immobile patients were documented “at risk” of PU – Medical record review of 834 VA LTC pts: overall adherence to 6 critical best PUP practices (such as standardized risk assessment and regular repositioning) was 50% • Kent, Cowan & Garvan 2014 (unpublished) – Veteran sample – Poor agreement between RD assessment of nutritional risk and RN documentation of nutritional risk (Braden Scale nutrition sub-score); RD nutritional assessment of severe nutritional compromise strongly associated with PU (low nutritional sub-score of Braden was not) Discerning PUP “Best Practices” • Evidence should be readily available for documented “best practices” • Best Practices for Prevention of Medical Device-Related Pressure Ulcers (NPUAP poster): – http://www.npuap.org/resources/educationaland-clinical-resources/best-practices-forprevention-of-medical-device-related-pressureulcers/ (evidence cited on poster?) PUP Efforts: SUMMARY: HELPFUL TIPS TO MAKING A SUCCESSFUL PUP PROGRAM Implementing Successful PUP Initiative AHRQ Toolkit says to address six questions: 1. Are we ready for this change? 2. How will we manage change? 3. What are the best practices in pressure ulcer prevention that we want to use? 4. How should those practices be organized in our hospital? 5. How do we measure our pressure ulcer rates and practices? 6. How do we sustain the redesigned prevention practices? Remember ABCDE • Administrative support • Bundling care practices • Creating culture of change, commitment, and communication • Documentation • Education and Evidence-Based References • Baranoski S. (2006). Raising awareness of pressure ulcer prevention and treatment. Adv Skin & Wound Care. 19, 398-407. • Lyder CH, Ayello EA (2009). Annual checkup: the CMS pressure ulcer present-on-admission indicator. Adv Skin & Wound Care. 22 (10), 476-84. • Office of Inspector General (OIG) CAP Report evaluating implementation of VHA Handbook 1180.02 “Prevention of Pressure Ulcers” in VHA facilities • Cowan, L & Garvan, C. (2014). Online Survey of VA Wound Providers. Poster presentation at SERWOCN, August 27, 2014, Montgomery, AL. • Garcia, A & Demers, C (VeHU Presentation September 18, 2014). TEAM: Together Everyone Aims for More: Interprofessional Approaches to Pressure Ulcer Prevention (PUP) • Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) evidence-based best practices (EBBP) for pressure ulcer prevention in “Toolkit for Improving Quality of Care” (2011) • Katzenbach J & Smith D. 1993. The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the Highperformance Organization. Harvard Business School Press. • Fogerty, M., Abumrad, N., Nanney, L., Arbogast, P., Poulose, B., & Barbul, A. (2008). Risk factors for pressure ulcers in acute care hospitals. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 16, 11-18. • Cowan, L., Stechmiller, J., Rowe, M., & Kairalla, J. (2012). Enhancing Braden pressure ulcer risk assessment in acutely ill adult Veterans. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 20, 137-148. • Soban, L., Hempel, S., Munjas, B., Miles, J. & Rubenstein, L. (2011). Preventing pressure ulcers in hospitals: A systematic review of nurse-focused quality improvement interventions. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 37 (6), 245-265. • Berlowitz et al. (2011). Preventing Pressure Ulcers in Hospitals: A Toolkit for Improving Quality of Care. Retrieved from AHRQ website at: http://www.ahrq.gov/pressureulcertoolkit • Sullivan, N. & Schoelles, K. (2013). Preventing in-facility pressure ulcers as a patient safety strategy. Annals of Internal Medicine, 158(5), 410—W186. • Cowan, L. & Garvan, C. (2014). Online Survey of VA Wound Providers. Poster Presentation at NF/SG VHS Research Day, May 16, 2014. • Niederhauser et al. 2012 – Systematic Review of 12 studies • Sullivan & Schoelles 2013 • Falise et al. 2014 PHHP Honor’s Thesis (in press)