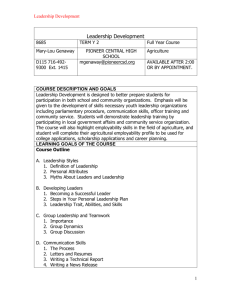

2. Employability skills and categories

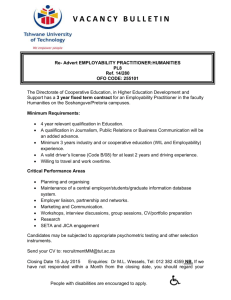

advertisement