International Trade

advertisement

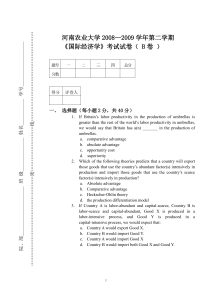

International Trade Chapter 1 Introduction to International Trade 1.1 The definition of international trade International trade can be defined as the exchange of goods and services produced in one country (or district) with those produced in another country(or district). The reasons for international trade A. The uneven distribution of natural resources B. International specialization C. Different Patterns of demand among nations D. Economies of scale E. Innovation or variety of style Even the IBM PC Isn’t All-American Total manufacturing cost: US$860 Portion made overseas: US$625 In u.s. owned plants $230 In foreign-owned plants $395 $860 $625 73% Distribution of Manufacturing Parts Monitor Korea Semiconductors Japan Power supply Japan Graphics Printer Japan Floppy Disk Drives Singapore Assembly of disk drives U.S Keyboard Japan Case and final Assembly U.S Even the Boeing 777 Isn’t All American The suppliers come from U.S. ,Japan, France, Canada, Italy, Australia, South Korea, United Kingdom So it is increasingly difficult to say what is a “U.S.” product; what is “Japanese” product. 1.2. The history of international trade development The first beginning of international trade The development of international trade in different social period 1.3. The different forms of international trade 1.3.1.Export Trade / Import Trade / Transit Trade Re-Export / Re-Import; Net Export / Net Import 1.3.2. General Trade / Special Trade General Trade: country territory. (Japan,United Kingdom, Canada Australia, East Europe) General Import / General Export Special Trade: Customs Territory.(German, Italy, Swiss) 1.3.3. Visible Trade / Invisible Trade 1.3.4 Direct Trade / Indirect Trade / Entrepot Trade 1.3.5 Trade by Roadway / Trade by Seaway / Trade by Airway / Trade by Mail Order 1.3.6 Free-Liquidation Trade / Barter Trade 1.4 . Another basic concepts about international trade 1.4.1. amount of foreign trade total amount of import and export for a country in definite period. 1.4.2. amount of international trade total amount of export for all countries in definite period. 1.4.3. trade balance favorable balance: export >import adverse balance: export<import (surplus) (deficit) 1.4.4. commodity structure primary commodities Industry commodities (finished goods) 1.4.5. factors of production a. capital, b. human resources or labor c. property resources including land 1.5 The difference between domestic trade and international trade 1.5.1. different effect to economy development 1.5.2. different environment social and culture / law and economic policy currency system 1.5.3. difficult movement for factors of production among nations 1.5.4. more risks when you do international business Credit; exchange rate; Business; Transportation; Price; Politics. 1.6 国际商务环境 外运公司 保险公司 进口商 生产厂家 出口商 商检局 银行 海关 税务局 Chapter 2 Foundations of Modern Trade Theory 2.1 The Mercantilism The mercantilists’ views on trade If a country could achieve a favorable trade balance (a surplus of exports over imports), it would enjoy payments received from the rest of the world in the form of gold and silver. The more precious metals a nation had, the richer and more powerful it was. To promote a favorable trade balance, the mercantilists advocated government regulation of trade. Tariffs, quotas, and other commercial policies were proposed by the mercantilists to minimize imports in order to protect a nation’s trade position. During the period 1500-1800 In Europe (England, Spain, France, Portugal, and the Netherlands) A group of men (merchants,bankers,government officials, and even philosophers) William Stafford, 1554—1612 The early stage mercantilism -----The theory of currency balance Thomas Mum, 1571—1641 The later period mercantilism ----The theory of trade balance 2.2. The theory of absolute advantage 2.2.1 Adam Smith, (1723 – 1790) a classical economist, was leading advocate of free trade (Laissez-Faire) “Inquiry into the Nature and causes of the Wealth of Nations” 1776 ---- The wealth of Nations 2.2.2 The main view on trade Trade is based on absolute advantage and benefits both nations. When each nation specializes in the production of the commodity of its absolute advantage and exchanges part of its output for the commodity of its absolute disadvantage, both nations end up consuming more of both commodities. 2.2.3 Illustration of absolute advantage Before Specialization in production X product output Labor time Y product output Labor time A country 4 1 1 1 B country 3 2 2 1 5 Labor time ----- 7X + 3Y After Specialization in production Y product X product output Labor time output Labor time A country 8 2 0 o B country 0 0 6 3 5 Labor time ------ 8X + 6Y > 7X + 3Y But if one nation has absolute advantage for both commodities,how to do? X product output A country B country 4 3 Y product Labor time 1 2 output 3 Labor time 1 2 1 2.3 The theory of comparative advantage 2.3.1 Economists - David Ricardo (1772-1823) He was born in 1772 and was the third of 17 children. His parents were very successful and his father was a wealthy merchant banker. They lived at first in the Netherlands and then moved to London. David himself had little formal education and went to work for his father at the age of 14. However, when, at the age of 21, he married a Quaker (against his parents wishes) he was disinherited and so set up on his own as a stockbroker. He was phenomenally successful at this and was able to retire at 42 and concentrate on his writings and politics. He developed many important areas of economic theory much of the theory he developed is still used and taught today. “Principles of Political Economy and Taxation” 1817 2.3.2. The key views on trade (The law of comparative advantage) Even if a nation has an absolute cost disadvantage in the production of both goods, a basis for mutually beneficial trade may still exist. The less efficient nation should specialize in the production and export of the commodity in which it has a comparative advantage (where its absolute disadvantage is less) The more efficient nation should specialize in and export that commodity in which it is relatively more efficient (where its absolute advantage is greater). Before specialization in production X product output Labor time Y product output Labor time A country 4 1 3 1 B country 3 2 2 1 5 Labor time: 7x + 5y After specialization in production X product Y product output Labor time output Labor time A country 8 2 0 0 B country 0 0 6 3 5 Labor time: 8x + 6y > 7x + 5y 2.3.3 The gains from trade U.S. U.K. Wheat (unit/man-hour) 6 1 Cloth (unit/man-hour) 4 2 If trade is possible 6W > 4C (since 6w=4c in the united states) 2C > 1W (since 2c=1w in the united kingdom) so, 12C > 6W > 4C Suppose the United States could exchange 6W for 6C with the United Kingdom The United States would then gain 2C (or save 1/2 hour of labor time) The United Kingdom gain 6C (or save three hours of labor time) So both nations can gain from the trade. 2.3.4 A lot of simplifying assumptions: a. only two nations and two commodities b. free trade c. perfect mobility of labor within each nation but immobility between the two nations d. constant costs of production e. no transportation costs f. no technical change g. the labor theory of value either labor is the only factor of production or labor is used in the same fixed proportion in the production of all commodities. labor is homogeneous 2.4. The opportunity cost theory 2.4.1. the definition of the opportunity cost The opportunity cost of a commodity is the amount of a second commodity that must be given up to release just enough resources to produce one additional unit of the first commodity. 2.4.2. the law of comparative cost The nation with the lower opportunity cost in the production of a commodity has a comparative advantage in that commodity; and a comparative disadvantage in the second commodity. U.S. U.K. Wheat (unit/man-hour) 6 1 Cloth (unit/man-hour) 4 2 In the U.S.A. 6w/4c=1w/? ?=2/3(c) So the opportunity cost of wheat is two-thirds (2/3) of a unit of cloth. In the U.K. 1w/2c=1w/? ?= 2 c So the opportunity cost of wheat is two (2) of a unit of cloth The opportunity cost of wheat is lower in the united states than in the united kingdom. The united states would have a comparative cost advantage over the united kingdom in wheat. 2.4.3. Transformation schedules production possibility curve; production possibility frontier This schedule shows various alternative combinations of two goods that a nation can produce when all of its factor inputs (land, labor, capital, entrepreneurship) are used in their most efficient manner. Production possibility schedules for wheat and cloth in the United States and the United Kingdom Under constant costs United States Wheat Cloth cloth United Kingdom Wheat United States Cloth 120 180 150 120 90 60 30 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 30 60 90 wheat 120 150 180 United States Wheat 180 150 120 90 60 30 0 Cloth 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 cloth United Kingdom Wheat 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 United Kingdom Cloth 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 20 40 60 wheat cloth cloth United States United Kingdom 120 120 100 80 100 80 60 60 40 40 20 20 0 30 60 90 wheat 120 150 180 0 20 40 60 wheat For each 30W that the United States gives up, just enough resources are released to produce an additional 20C. That is, 30W=20C ,so 1W=2/3C Thus,the opportunity cost of one unit of wheat in the United States is 2/3C cloth cloth United States United Kingdom 120 120 100 80 100 80 60 60 40 40 20 20 0 30 60 90 wheat 120 150 180 0 20 40 60 wheat In U.S.A Marginal rate transformation MRT= Cloth / Wheat = slope = 120/180 = 2/3 Same, the opportunity cost of wheat in the U.K. is 1W=2C Marginal rate transformation MRT= Cloth / Wheat = slope = 120 / 60 = 2 2.4.4. Opportunity Costs and relative commodity prices On the assumptions that prices equal costs of production and that the nation does produce both some wheat and some cloth, the opportunity cost of wheat = the price of wheat relative to the price of cloth In the United States In the United Kingdom Pw / Pc = 2/3 Pw / Pc = 2 Pw / Pc (U.S) < Pw / Pc(U.K.) it is a reflection of the United states’s comparative advantage in wheat. Similarly, Pc/Pw(U.K.) < Pc/Pw(U.S.) it is a reflection of the United Kingdom’s comparative advantage in cloth. 2.5 The basis for and the gains from trade under constant costs 2.5.1 The basis for trade under constant costs The difference in relative commodity prices between the two nations is a reflection of their comparative advantage and provides the basis for mutually beneficial trade. constant opportunity costs a. The factors of production are perfect substitutes for each b. All units of a given factor are of the same quality 2.5.2 Illustration of the gains from trade cloth cloth United States United Kingdom B’ 120 120 E 70 60 50 40 A A’ E’ B 0 90 wheat 110 180 0 40 60 70 wheat specialization can result in production gain 180W + 120C > (90+40)W + (60+40)C if the U.S. exchanges 70w for 70c with the U.K, (trade) it ends up consuming at point E (110w + 70c) , gain 20W + 10 C U.K. ends up consuming at E’ and gains 30 W + 10 C So, trade can result in consumption gains for both countries. 2.6 Comparative advantage with more than two commodities Commodity A B C D E Price in the U.S. $2 4 6 8 10 Price in the U.K. £6 4 3 2 1 £1=$2 £1=$3 $12 8 6 4 2 $18 12 9 6 3 If the exchange rate between the dollar and the pound is £1 = $2 U.S will export commodities A and B; U.K. ----- E,D If £1 = $ 3 U.S. will export A.B.C; U.K. will export E,D 2.7 Comparative advantage with more than two nations Nation Pw / Pc A 1 B C 2 D 3 E 4 5 If the equilibrium Pw / Pc = 3 Nation A, B will export wheat to Nations and E in exchange for cloth. If a trade equilibrium Pw/Pc = 4, Nations A,B,C will export wheat to Nation E in exchange for cloth If the equilibrium Pw/Pc =2 with trade, ? Chapter 3 The Standard Theory of International Trade 3.1. The Production Frontier with Increasing Costs Increasing opportunity costs mean that the nation must give up more and more of one commodity to release just enough resources to produce each additional unit of another commodity. y Nation 1 A y1 y2 y3 y4 y1y2<y2y3<y3y4< y4y5 - y y5 0 10 30 50 70 xB 90 110 130 x y 140 120 Nation 2 B’ 100 80 60 X1x2<x2x3<x3x4 A’ 40 20 x X4 X3 X2X1 Production Frontiers of Nation 2 with increasing costs 3.1.2 Reasons for increasing opportunity costs and different Production frontiers a. Resources or factors of production are not homogeneous b. Resources or factors of production are not used in the same fixed proportion or intensity in the production of all commodities. c. The difference in the production frontiers of two nations is due to the fact that the two nations have different factor endowments or resources at their disposal and /or use different technologies in production. 3.2 Community Indifference Curves 3.2.1 Illustration of community indifference curves A community indifference curve shows the various combinations of two commodities that yield equal satisfaction to the community or nation. Y 100 A T E III 80 B N H C 60 II D I 40 Nation 1 20 0 10 30 50 70 90 X 3.2.2 The marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS) MRS of X for Y in consumption refers to the amount of Y that a nation could give up for one extra unit of X and still remain on the same indifference curve. In Nation 1 ,the substitution of x for y ,MRS(N) > MRS(A) The decline in MRS or absolute slope of an indifference curve is a reflection or the fact that the more of X and the less of Y a nation consumes; The declining slope of the curve reflects the diminishing marginal rate of substitution (MRS) of X for Y in consumption. 3.3. Equilibrium in Isolation 3.3.1. Illustration of Equilibrium in Isolation Nation 1 y A 60 I PA=1/4 B x 0 10 30 50 70 90 110 130 In the absence of trade (or autarky), a nation is in equilibrium when it reaches the highest indifference curve possible given its production frontier. 3.3.2. Equilibrium Relative Commodity Prices and Comparative Advantage The equilibrium relative commodity price in isolation is given by the slope of the common tangent to the nation’s production frontier and indifference curve at the autarky point of production and consumption. PA = Px / Py=1/4 PA’ = Px / Py = 4 PA < PA’ So, Nation 1 has a comparative advantage in commodity X and Nation 2 in commodity Y. 3.4. The basis for and the Gains from trade with increasing costs 3.4.1.Illustrations With trade, Nation 1 moves from point A to point B in production. By then exchanging 60X for 60Y with Nation 2 Nation 1 ends up consuming at point E(on indifference curve) Thus, Nation 1 gains 20X and 20Y from trade. A ---- E A. With trade, each nation specializes in producing the commodity of its comparative advantage and faces in creasing opportunity costs. B. Specialization in production proceeds until relative commodity prices in the two nations are equalized at the level at which trade is in equilibrium. 3.4.2. Equilibrium relative Commodity Prices with trade The process of specialization in production continues until relative commodity prices (the slope of the production frontiers) become equal in the two nations PB = PB’ The equilibrium relative commodity price with trade is the common relative price in both nations at which trade is balanced 3.4.3. Incomplete Specialization Under constant costs, both nations specialize completely in production of the commodity of their comparative advantage Under increasing opportunity costs, there is incomplete specialization in production in both nations. The reason for this is that as Nation 1 specializes in the production of X, it incurs increasing opportunity costs in producing X. 3.4.4. The gains from exchange and from specialization A nation’s gains from trade can be broken into two components: The gains from exchange The gains from specialization 3.5. Trade based on differences in tastes with increasing costs, even if two nations have identical production possibility frontiers (which is unlikely), there will still be a basis for mutually beneficial trade if tastes, or demand preferences, in the two nations differ. The nation with the relatively smaller demand or preference for a commodity will have a lower autarky relative price for, and a comparative advantage in, that commodity. Illustration A, A’ in isolation PA < PA’ Nation 1 has a comparative advantage in X and Nation 2 in Y. A(40,160)----B ---- C ---- E(60,180) gain 20 X + 20Y in Nation 1 A’(160,40)-----B’ ---- C’ ---- E’(180,60) gain 20X+20Y in Nation 2 Problem 5. (page 73) On one set of axes,sketch Nation 1’s supply of exports of commodity X so that the quantity supplied (QS) of X is QSx=0 at Px/Py=1/4, QSx=40 at Px/Py=1/2, QSx=60 at Px/Py=1, and QSx=70 at Px/Py=3/2, On the same set of axes, sketch Nation 2’s demand for Nation 1’s exports of commodity X so that the quantity demanded (QD) of X is QDx=40 at Px/Py=3/2,QDx=60 at PxPy=1, and QDx=120 at Px/Py=1/2 (b) What would happen if Px/Py were 3/2 Excess supply If Px/Py=3/2, QSx=70; QDx=40, Supply>Demand; Px/Py will come down Excess demand (a) Determine the equilibrium relative commodity price of the exports of commodity X with trade. (c) What would happen if Px/Py=1/2 When Px / Py = 1, QSx = QDx = 60; So, the equilibrium relative commodity price of the exports of commodity x with trade is 1 If Px/Py=1/2, QSx=40; QDx=120, Demand>Supply; Px/Py will rise Chapter 4 Demand and Supply, Offer Curves, and the Terms of Trade 4.1 Theory of Reciprocal Demand John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) Essays on some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy (1844), Principles of Political Economy (1848). Main view on trade: The actual price at which trade takes place depends on the trading partners’ interacting demands. 4.2 The equilibrium relative commodity price with trade --- Partial equilibrium analysis 4.3 Offer Curves Alfred Marshall (1842-1924 The Pure Theory of Foreign Trade, 1879 Principles of Economics, 1890. 4.3.1 Definition of offer curves ( reciprocal demand curves) offer curves of a nation shows how much of its import commodity the nation demands to be willing to supply various amounts of its export commodity. The offer curve of a nation shows the nation’s willingness to import and export at various relative commodity prices. 4.3.2. Derivation and shape of the offer curve of Nation 1 4.3.3. Derivation and shape of the offer curve of Nation 2 4.4 The equilibrium relative commodity price with trade ---- general equilibrium analysis Only at this equilibrium price will trade be balanced between the two nations. 4.4. Terms of trade 4.4.1. Definition of the terms of trade The terms of trade of a nation are defined as the ratio of the price of its export commodity to the price of its import commodity. Terms of trade = (Export Price Index / Import Price Index) X 100 N = ( Px / Pm ) x 100 An improvement in a nation’s terms of trade requires that the prices of its exports rise relative to the prices of its imports over the given time period. Px = 105; Pm = 104; Px = 96; Pm = 94; Px = 106; Pm = 98; A smaller quantity of export goods sold abroad is required to obtain a given quantity of imports What is a deterioration in a nation’s terms of trade ? Commodity terms of trade, 1995 (1990=100) Country Export Price index Import Price index Terms of Trade Japan United States United kingdom Germany Canada Australia 145 109 113 108 101 94 105 106 113 109 103 110 138 103 100 99 98 85 Japanese terms of trade rose by 38 percent (145/105)x100 over 1990 – 1995 period. This means that to purchase a given quantity of imports, Japan had to sacrifice 38 percent fewer exports; Conversely, for a given number of exports, Japan could obtain 38 percent more imports. So. Japanese terms of trade improved. Whose terms of trade worsened? Chapter 5 Factor Endowments and the(要素禀赋说) Heckscher-Ohlin Theory (赫克雪尔-俄林定理) (Trade Model Extensions and applications) 5.1 introduction In 1919, Heckscher published “The Effect of Foreign Trade on the Distribution of Income” In 1933 Ohlin published International Trade” “Interregional and Ohlin was awarded the 1977 Nobel prize in economics for his contribution to the theory of international trade. 5.2. Assumptions of the theory (1) two nations, two commodities (X,Y), and two factors of production (labor ,capital) (2) Both nations use the same technology in production; (3) The same commodity is labor intensive in both nations X --- labor intensive ;Y---- capital intensive (4) Constant returns to scale; (5) Incomplete specialization in production; (6) Equal tastes in both nations; (7) Perfect competition in both commodities and factor markets; (8) Perfect internal but no international mobility of factor; (9) No transportation costs, tariffs, or other obstructions to the free flow of international trade; (10) All resources are fully employed; (11) Trade is balanced. 5.3 Factor intensity, Factor abundance, and the shape of the production frontier 5.3.1. factor intensity The commodity Y is capital intensive if the capital-labor ratio (K/L) used in the production of Y is greater than K/L used in the production of X ( is not the absolute amount of K and L.) In Nation 1, K/L in X: 1/4 in Y : 1 So, X is L- intensive commodity; Y is K-intensive In Nation 2, K/L in X: 1 in Y: 4 So, X is L-intensive commodity, Y is K-intensive The obvious question is : Why does Nation 2 use more K-intensive production techniques in both commodities than Nation 1 ? Why is capital relatively cheaper in Nation 2 ? 5.3.2. Factor abundance a. In terms of physical units : the overall amount of capital and labor available to each nation. The ratio of the total amount of capital to the total amount of labor. Nation 2 is capital abundant if TK2/TL2 > TK1/TL1 b. In terms of relative factor prices: the rental price of capital and the price of labor time in each nation. The ratio of the rental price of capital to the price of labor time Pk/PL= r/w r: interest rate; w: wage rate Nation 2 is capital abundant if PK2/PL2 < PK1/PL1 or r2/w2 < r1/w1 5.3.3 Factor abundance and the shape of the production frontier Nation 1 is the L-abundant nation; Y X is the L-intensive commodity Nation 2 So, Nation 1 can produce relatively more of commodity x Nation 1 X 5.4 The Heckscher-Ohlin Theory (Factor proportions; Factor endowment theory) 5.4.1 views of the Heckscher - Ohlin theorem 1. Differences in relative factor endowments among nations underlie the basis for trade. 2. A nation will export the commodity in the production of which a relatively large amount of its abundant and cheap resource is used. 3. Conversely, it will import commodities in the production of which a relatively scarce and expensive resource is used. 4.With trade the relative differences in resource prices between nations tend to be eliminated 5.4.2 General equilibrium framework of the Heckscher - Ohlin theory Tastes Distribution of ownership of factors of production Demand for final commodities Derived demand for factors Commodity prices Factor prices Technology Supply of factors 5.5 Illustration of the Heckscher - Ohlin Theory 5.6 Factor - Price Equalization and Income Distribution Paul Samuelson ----- 1970 Nobel Prize in economics "International Trade and the Equalization of Factor Prices", 1948 Factor-price equalization theorem referred to as the H-O-S theorem 5.6.1 The factor-price equalization theorem International trade will bring about equalization in the relative and absolute returns to homogeneous factors across nations. Both relative and absolute factor prices will be equalized. Nation 1 is Labor abundant X is L-intensive commodity, X is with comparative advantage. The relative price of labor (wage rate) is lower Nation 2 is capital abundant , Y is K-intensive commodity, Y is with comparative advantage. The relative price of capital (interest rate) is lower and the relative price of labor is higher Specializes in the production of commodity X Specializes in the production of commodity Y,reduces production of X (L-intensive) The relative demand for labor rises The relative demand for labor falls Price of labor (wage) rises Price of labor (wage) falls 5.6.2 Relative factor-price equalization This is the process by which relative factor prices are equalized Trade also equalizes the absolute returns to homogeneous factors. 5.6.3 Effect of trade on the distribution of income 1. Trade increases the prices of the nation’s abundant and cheap factor ; And reduces the price of its scarce and expensive factor 2. International trade causes real wages and the real income of labor to fall in a capital-abundant and labor-scarce nation. International trade causes real wages and the real income of labor to rise in a labor-abundant and capital-scarce nation. Should the U.S. government restrict trade? The loss that trade causes to labor is less than the gain received by owners of capital. Exercise Draw a figure similar to following figure but showing that the Heckscher-Ohlin model holds, even with some difference in tastes between Notion 1 and Nation 2 5.7 Empirical tests of the Heckscher-Ohlin model 5.7.1 The Leontief Paradox The results of Leontief’s test: the United States export L-intensive commodities and import K-intensive commodities. Page 133. Case study 5-5 1947, U.S.A. Export Import Substitutes $2550,780 $3091,339 Labor (man-years) 182 170 Capital/Labor $14010 $18,180 Capital 5.7.2 Explanations of the Leontief Paradox 1. The year 1947 is too close to World War II to be representative. 2. The U.S. dependence on imports of many natural resources. 3. U.S. tariff policy 4. Ignored human capital (education, job training,and health embodied in workers) U.S. labor embodies more human capital. 5. Factor-intensity reversal A given commodity is the L-intensive commodity in the L-abundant nation and the K-intensive commodity in the K-abundant nation Chapter 6 New International Trade Theories 6.1 Theory of Increasing Returns to scale 6.1.1 Main views (1).There is still a basis for mutually beneficial trade based on economies of scale, even if two nations are identical in every respect. (2) When economies of scale are present, total world output of both commodities will be greater than without specialization (3) With trade, each nation then shares in these gains. 6.1.2 Illustration of Trade based on Economies of scale Nation 1: from A to B Export X & import Y from B to E Nation 2: from A to B’ Export Y & import X from B’ to E Each nation would end up consuming at point E on indifference curve II Which is higher than curve I Examples: U.S. exports and theory imports, 1995 (in Billions of Dollars) 6.2 Intra-Industry Trade Category Export Imports (Differentiated Product Theory) Autos 60.5 124.5 Intra-industry trade refers to the exchange between nations Computers of differentiated products of 39.6 the same industry .56.4 Telecommunications equipment 19.8 15.3 paper Chemicals 14.5 43.0 12.9 25.5 steel Machine tools 5.8 5.2 23.0 16.1 6.6 24.1 6.6 7.9 3.9 2.4 Electrical generating machinery Meat products Vegetables and fruits 6.2.1 main views of intra-industry trade theory (differentiated products theory (1) Intra-industry trade arises in order to take advantage of important economies of scale in production. (2) With differentiated products produced under economies of scale, pretrade relative commodity prices may no longer accurately predict the pattern of trade. (3) With intra-industry trade based on economies of scale it is possible for all factors to gain.(will not lower the return of the nation’s scarce factor.) (4)Intra-industry trade is related to the sharp increase in international trade in parts or components of a product. 6.2.2 Measuring intra-industry trade Intra-industry trade index ( T ) T = 1 - IX – MI / (X + M) X ----- the value of exports of a particular industry M ----- the value of imports of a particular industry If X=M T=1, intra-industry trade is maximum If X=0,or M=o, T=0, NO intra-industry trade . Example: USA in 1995, export computers USD39.6 billion Import computers USD56.4 billion So, T = 1 – I39.6 – 56.4I/(39.6+56.4) T = 0.825 6.3 Technological Gap Theory (Innovation and Imitation Theory) A country exports a new product produced with advanced technological until imitators in other countries take away its market. The innovating nation will have introduced a new product or process Technological changes and innovation can affect comparative advantage and the pattern of trade. Q Technological gap and international trade Production in nation 1 Export of nation 1,import of nation 2 t0 t1 t2 t3 Export of nation 2,import of nation 1 Imitation lag Reaction lag Demand lag T Mastery lag Production in nation 2 6.4 Product Life Cycle Theory Many manufactured goods undergo a predictable trade cycle. During this cycle, a nation initially is an exporter, then loses its export markets, and finally becomes an importer of the product. A product goes through five stages: (1) Manufactured good is introduced to home market. (new-product phase) (2) Domestic industry shows export strength. (product-growth phase) (3) Foreign production begins.(product maturity phase) (4) Domestic industry loses competitive advantage.(product decline stage) (5) Import competition begins.(product decline stage) The product cycle model Quantity Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4 Stage 5 (New product) (Product growth) (product maturity) (product decline) (abdicate market) import consumption export production export consumption import 0 A B production C D Innovating country imitating country Time 6.5 Transportation costs, Environmental standards, and International Trade 6.5.1 Transportation costs and Non-traded Commodities IP2 – P1I > Transportation cost Traded commodities IP2 – P1I < Transportation cost Non-traded commodities The price of non-traded commodities is determined by domestic demand and supply conditions. The price of traded commodities is determined by world demand and supply conditions. Partial Equilibrium analysis of Transportation cost (2). Transportation costs reduce the volume and gains from trade. (3). Transportation costs lead to the different prices in two nations for same commodity. (4). Factor price will not be completely equalized . (1). Transportation costs reduce the level of specialization in production (5) Transportation cost is shared by the two nations. 6.5.2 Transportation Costs and the Location of Industry Resource-oriented industries Market-oriented industries Footloose industries 6.5.3 Environmental standards, Industry Location, and international Trade Chapter 7 The Theory of Protective Trade 7.1 The theory of protective tariff Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) 汉密尔顿 “Report on Manufactures” - submitted to Congress 1791 He recommended specific policies to encourage manufactures: protective duties prohibitions on rival imports exemption of domestic manufactures from duties encouragement of "new inventions . . . particularly those, which relate to machinery." 7.2 The theory of protecting infant industry List, (Georg) Friedrich ( 1789 --- 1846) (李斯特) German-U.S. economist His best-known work was The National System of Political Economy (1841). Political Economy (1827) He first gained prominence as the founder of an association of German industrialists that favored abolishing tariff barriers between the German states He maintained that a national economy in an early stage of industrialization required tariff protection to stimulate development 7.3 The theory of foreign trade multiplier John Maynard Keynes (1883 – 1946) “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money” 《就业、利息和货币通论》 7.3.1 Determination of the equilibrium national income in a closed economy Gross National Product (GNP) Total final value of goods and services produced in a national economy over a particular period of time,usually one year. National income (Y) The sum of all payments made to sum factors of production. Equilibrium of National economy GNP = Y GNP = C + I C ---- Total consumption I ---- Total investment Y=C+S C+I=C+S S ---- Total saving I=S 7.3.2 The Multiplier in a Closed Economy Y =Kx K= Y=C+S I Y = I C Y Y Y- C I=S Y=I+C I=Y–C 1 = 1- C Y Marginal propensity to consume (MPC) K = 1 1 - MPC Y =Kx 1 K = 1 - MPC I MPC = 0.9 K = 1 / 0.1 = 10 MPC = 0 K=1/1=1 MPC = 1 K= S Y Y = Marginal Propensity to Save (MPS) C + S MPS = 1 - MPC S = 1Y C Y K = 1 / MPS The closed economy Keynesian multiplier (K) 7.3.3 Equilibrium condition in an open economy GNP = C + I + X C --- domestic consumption I --- domestic investment X --- export Y=C+S+M S --- domestic saving M --- import GNP = Y I+X=S+M C+I+X=C+S+M S–I=X–M If S>I (domestic demand declines) X should be increased If S<I (higher domestic demand ) M should be increased 7.3.4 The foreign trade multiplier I+X= S+M I+ S = MPS X= S+ M …….(1) S = (MPS) ( Y ) ….. (2) Y Marginal Propensity to Save M = MPM Y I+ M = (MPM) ( Y ) ….. (3) Marginal Propensity to import X= Y (MPS +MPM) 1 ( I+ X) Y= MPS + MPM 1 Foreign trade multiplier (K’) is MPS + MPM I+ X= S+ M X- M= S MPS = Y S I+ Y= S MPS Y= 1 [ MPS I+( X- M )] Y= 1 [ 1-MPC I+( X- M )] Y= 1 K [ 1-MPC I+( X- M )] Chapter 8 Trade Restrictions: Tariff Barriers 8.1 The tariff concept 8.1.1 definition A tariff is a tax levied on a commodity when it crosses the boundary of a customs area. Import tariff, which is a tax levied on an imported product. Export tariff, which is a tax imposed on an exported product. 8.1.2 purposes Protective tariff is designed to insulate import-competing producers from foreign competition. Revenue tariff is imposed for the purpose of generating tax revenues and may be placed on both exports and imports. 8.1.3 Means of Collecting Tariffs specific tariff a fixed amount of money per physical unit of the imported product. ad valorem tariff compound tariff a fixed percentage of the value of the imported product. a combination of a specific and an ad valorem tariff. 8.2 Partial Equilibrium Analysis of a Tariff a small nation imposes a tariff on imports competing with the output of a small domestic industry. Then the tariff will affect neither world prices nor the rest of the economy. 8.2.1 Partial Equilibrium effects of a Tariff The trade effect --- the decline in imports = 30X (BN+CM) The Revenue effect --- the revenue collected by the government = $30 (MJHN) The Consumption effect of the tariff --- the reduction in domestic consumption = 20X (BN) The production effect --- the expansion of domestic production resulting from the tariff = 10X (CM) Substitution effect or protection effect 8.2.2 Effect of a Tariff on consumer and Producer Surplus consumer surplus is difference between what consumers would be willing to pay for each unit of the commodity and what they actually pay Without tariff When Q <, or =D0 Consumers would be willing to pay OD0FG g Consumers actually pay OD0FA So, consumer surplus is: AFG When tariff = t and P=P*+t Consumers would be willing to pay OD1EB. Consumers actually pay OD1EB So, consumer surplus is: BEG The tariff reduce the consumer surplus AFG – BEG = AFEB=a+b+c+d Producer surplus is the revenue producers receive over and above the minimum amount required to induce them to supply the goods (profit) Without tariff Producer’s revenue = e+f Producer’s cost = f g When tariff = t Producer surplus = e Producer’s revenue = a+b+e+f+g Producer surplus = a+e Producer’s cost = b+f+g The tariff increases producer surplus by area a 8.3 The degree of protection afforded by a tariff 8.3.1 Tariff Level Tariff Level = Amount of Import tariff / Amount of import x100% Tariff Level = ∑C / ∑P = ∑(PxR) / ∑P 8.3.2 Nominal Rate of Protection --- NRP NRP = (Pd – Pa) / Pa Pd: the price of a commodity in domestic market Pa : The price of a commodity in abroad market NRP = tariff rate of the final commodity = t (without considering the effect of exchange rate) 8.3.3 Effective Rate of Protection --- ERP ERP indicates how much protection is actually provided to the domestic processing of the import competing commodity ERP signifies the total increase in domestic productive activities (value added) that an existing tariff structure makes possible, compared with what would occur under free-trade conditions. ERP =(V’ – V) / V V’: value added in domestic productive activities V: value added in abroad, free trade conditions ERP =(V’ – V) / V V’ = (P2 + C2) – (P1 + C1) P2: price of final product C2: amount of import duty of final product P1: price of input C1: amount of import duty of input V = P2 – P1 So, ERP = (P2 + C2) – (P1 + C1) – (P2 – P1) P2 – P1 =(C2 –C1) / (P2 – P1) ERP = (C2 –C1) / (P2 – P1) = C2 C1 X P1 P2 P1 P2 1 – P1/P2 P1/P2 = ai the ratio of the cost of the imported input to the price of the final commodity in the absence of tariffs the nominal tariff rate on consumers of the final commodity C2/P2 = t C1/P1 = ti the nominal tariff rate on the imported input ERP = t – ai X ti 1 – ai 8.3.4 Varies of tariff rate Import Duty (Norma Tariff) a. Common duties b. Most – favoured Duties Most – Favored – Nation Treatment c. Preferential Duties d. Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) Import Surtax a. Anti – Dumping duty b. Anti – Subsidy duty c. Emergency Tariff d. Penalty Tariff e. Retaliatory Tariff Chapter 9 Non-tariff Trade Barriers and the New Protectionism 9.1 Import quotas a quota is the most important non-tariff trade barrier. It is a direct quantitative restriction on the amount of a commodity allowed to be imported or exported. 9.1.1 The effects of an import quota Import quotas ---- used by all industrial nations to protect their agriculture ---- used by developing nations to stimulate import substitution of manufactured products and for balance-of-payments reasons. 9.1.2 Comparison of an Import Quota to an Import Tariff a. With a given import quota, an increase in demand higher domestic price and greater domestic production With a given import tariff, an increase in demand domestic price and domestic production unchanged but will result in higher consumption and imports b. The quota involves the distribution of import quota monopoly profits bribe government officials c. An import quota limits imports to the specified level with certainty, while the trade effect of an import tariff may be uncertain. 9.1.3 the forms of quotas Global Quota (Unallocated Quota) Autonomous Quota (Unilateral Quota) Absolute Quota Country Quota Agreement Quota Importer Quota Tariff Quota 9.2 Other non-tariff Barriers 9.2.1 Voluntary Export Restraints (VERs) An importing country induces another nation to reduce its exports of a commodity “voluntarily,” under the threat of higher all-round trade restrictions, when these exports threaten an entire domestic industry. 9.2.2 Import License System Open General License --- OGL Specific License ---SL 9.2.3 9.2.4 9.2.5 9.2.6 Foreign Exchange control Advanced Deposit Minimum Price Internal Taxes 9.2.7 State Monopoly (State trade) 9.2.8 Discriminatory Government Procurement Policy 9.2.9 Customs Procedures 9.2.10 Technical Barrier to Trade technical standard health and sanitary regulation packing and labeling regulation 9.3 Means of stimulating export and controlling export 9.3.1 Export Credit Supplier’s credit The exporter’s bank provide loans to the nation’s exporters. Buyer’s credit (Tied Loan) exporter The exporter’s bank provide loans to foreign buyers or importer bank. Exporter’s bank Importer Imorter’s bank Buyer’s credit Supplier’s credit Buyer’s credit 9.3.2 Export Credit Guarantee System 9.3.3 Dumping and Export Subsidies Dumping is the export of a commodity at below cost or at least the sale of a commodity at a lower price abroad than domestically. Three forms of dumping persistent dumping ----is the continuous tendency of a domestic monopolist to maximize total profits by selling the commodity at a higher price in the domestic market than internationally Predatory dumping ----(Intermittent Dumping) is the temporary sale of a commodity at below cost or at a lower price abroad in order to drive foreign producers out of business, after which prices are raised to take advantage of the newly acquired monopoly power abroad. Sporadic dumping ---is the occasional sale of a commodity at below cost or at a lower price abroad than domestically in order to unload an unforeseen and temporary surplus of the commodity without having to reduce domestic prices. Two forms of subsidy Direct Subsidy Indirect Subsidy 9.3.4 Exchange Dumping Decreasing the exchange rate (devaluate the currency) to stimulate the nations’ export 9.4 GATT and WTO 9.4.1 The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) GATT signed by 23 nations in 1947(Oct. 30) became effective on Jan. 1st 1948 to decrease trade barriers and to place all nations on an equal footing in trading relationships. 9.4.2 The principles of GATT a. b. c. Nondiscrimination The principles of most favored nation and national treatment The national-treatment principle Elimination of non-tariff trade barriers Consultation among nations in solving trade disputes within the GATT framework. GATT Negotiating Rounds Negotiating Coverage Round and Addressed tariffs Geneva (Swiss) Annecy (France) Torquay (U.K.) Geneva Dillon Round (Geneva) Kennedy Round (Geneva) Addressed tariff non-tariff barriers Tokyo Round Uruguay Round and Date Number of Participants Tariff Cut Achieved (%) 1947 1949 1951 1956 1960-1961 1964-1967 23 33 39 28 45 54 21 2 3 4 2 54 1973-1979 1986-1993 99 117 33 34 9.4.3 The World Trade Organization On January 1, 1995, the Uruguay Round took effect, GATT was transformed into the World Trade Organization. 9.4.4 How different is the WTO from the old GATT ? a. The WTO is a permanent international organization, headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, while the old GATT was basically a provisional treaty serviced b. The WTO has a far wider scope than the old GATT, bringing into the multilateral trading system, trade in services, intellectual property, and investment. c. The WTO also administers a unified package of agreements to which all members are committed; in contrast, the GATT framework included many side agreements whose membership was limited to a few nations. d. The WTO reverses policies of protection in certain “sensitive” areas (for example, agriculture and textiles) that were more or less tolerated in the old GATT. e. The WTO is not a government; individual nations retain their right to determine how they will make national laws conforming to their international obligations. Chapter 10 Regional Economic Integration 10.1 The forms of economic integration 10.1.1 Preferential trade arrangements ----- provide lower barriers on trade among participating nations than on trade with nonmember nations. This is the loosest form of economic integration ASENA (1967)----- Association of South East Asian Nations Members: Indonesia, Malaysia ,the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, Brunei, Vietnam 10.1.2 Free trade area ---- is the form of economic integration wherein all barriers are removed on trade among members, but each nation retains its own barriers to trade with nonmembers. NAFTA (1993) ----North American Free Trade Agreement Members: the United States, Canada, and Mexico 10.1.3 Customs union ---- allows no tariffs or other barriers on trade among members , and in addition it harmonizes trade policies (such as the setting of common tariff rates) toward the rest of the world. Benelux (1948)---- Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg 10.1.4 Common market ---- the free movement of goods and services among member nations; The initiation of common external trade restrictions against members; The free movement of factors of production across national borders within the economic bloc CACM (1960) --- Central American Common Market Members: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua Economic union ----- goes still further by harmonizing or even unifying the monetary and fiscal policies of member states. This is the most advanced type of economic integration. EU (1958/1994)---- The European Union 10.2 Trade-creating effect of customs unions 10.2.1 Trade creation ---- occurs when some domestic production of one customs-union member is replaced by another member’s lower-cost imports. Trade creation increases the welfare of member nations because it leads to greater specialization in production based on comparative advantage. 10.2.2 Illustration of a trade creating customs union A. USD30 Tariff rate 100% B. USD25 USD20 Nation 2 In Nation 1 Px = $1 In Nation 3 Px = $1.5 100% tariff rate of import commodity X Nation 2 import from Nation 1 = 50x – 20x = 30x If Nation 2 now forms a customs union with Nation 1 Nation 2 import from Nation 1 = 70x – 10x = 60x The area AGJC represents a transfer from domestic producers to domestic consumers, Net static gains to Nation 2 as a whole equal to $15 ---- the areas of shaded triangles CJM + BHN 10.3 Trade-Diverting Customs Unions 10.3.1 Trade diversion ---- Occurs when lower-cost imports from outside the union are replaced by higher-cost imports from another union member. Trade-diverting customs union results in both trade creation and trade diversion, therefore can increase or reduce the welfare of union members. 10.3.2 Illustration of a Trade-Diverting Customs Union A $35 40% B $26 x C $20 Nation 2 S1 and S3 are the free trade perfectly elastic supply curves of X of Nation 1 and Nation 3 With 100% tariff Nation 2 import from Nation 1 = 50x – 20x = 30X Forming a customs union with Nation 3 only; Nation 2 import from Nation 3 = 45x The welfare gain in Nation 2 from pure trade creation is $3.75 ----- the sum of the areas of the shaded triangles. The welfare loss from trade diversion is 10.4 Dynamic benefits from customs unions 10.4.1 Increased competition. 10.4.2 Economies of scale 10.4.3 Stimulus to investment. 10.4.4 Better utilization of the economic resources of the entire community.