Luke.Day1 - Vanderbilt Business School

advertisement

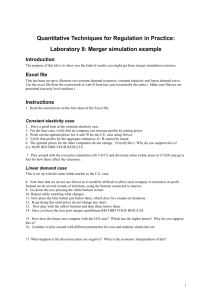

Quantitative Analysis Of Competitive Effects For Antitrust Day 1 Luke Froeb Owen Graduate School of Management Vanderbilt University April, 2003 Case Studies Showing How Modeling Is Used in Antitrust WorldCom and Sprint Branded Consumer Product Carnival and Princess Luke Froeb Owen Graduate School of Management Vanderbilt University WorldCom and Sprint Merger: Background Merger scrutinized by – U.S. Department of Justice – Federal Communications Commission – Interested third parties like Bell Atlantic Overlap in residential long distance service Regulatory restrictions keeping local phone companies out of market were soon to fall WorldCom and Sprint Merger: Methodology Estimate consumer choice model (demand) Estimate/Calibrate Firm Model (supply) Simulate “ownership” effect of merger Share Price World 16.5 Com Sprint 6.9 16.5 AT&T 56.4 17.6 Others 20.1 14.4 17.9 WorldCom and Sprint Merger: Simulated Merger Effects Demand estimation from bill “harvesting” – Inelastic demand – Predicted price increases for merging firms WorldCom: 5.4% Sprint: 8.9% Calibration from WorldCom’s margin – Small margins imply more elastic demand – Predicted price increases for merging firms WorldCom: 2.2% Sprint: 5.1% WorldCom and Sprint Merger: Mergers in a Post Entry World Does entry occur in response to merger? Entry by incumbent local exchange carriers (“Baby Bells”) – State level “experiments” show 25% share of long distance – What is merger effect in post entry world? Baby Bell entry cuts the industry average price effect in half Branded Consumer Goods Merger This is a real case that must be kept confidential, so numbers are disguised Entrant gained 25% share in two years Proposed Only to purchase rival brand 3 brands in “high end” segment Aggregate segment elasticity 1.5 Branded Consumer Goods Merger: Brand Elasticity, Prices, Shares A Price B Price C Price Price Share A Quantity 2.21 0.44 0.28 $20 35% B Quantity 0.39 2.16 0.28 $20 40% C Quantity 0.39 0.44 2.32 $20 25% Branded Consumer Goods Merger: Findings Estimated demand implies brands are fairly good substitutes for one another Predicted industry price increase of 4% Merging and 8% 12% brand price increases of 5% and 18% marginal cost reductions required to offset price increases Is Merger Prediction Consistent with Entry Experience? Incumbent brands did not reduce price in response to entry with a 25% share Implies entrant is bad substitute Yet, we get a significant price increase following merger Implies entrant is good substitute Is postmerger price increase consistent with no incumbent entry response? How to Answer Question Calibrate model to observed data “Undo” entry by raising price of recent entrant until zero quantity Compare price changes of remaining (incumbent) brands Entry effects are reverse of “undoing” entry effects Consumer Goods Merger: Entry Model Prices of incumbent brands barely change Quantity drops significantly Entrants steal quantity, but do not affect price In general, other firms do not much affect price A B ΔP –0.85% –0.95% ΔQ –10.3% –9.98% Consumer Goods Merger: How Can We Test this Prediction? Where from? did entrant’s quantity come 65% from “outside” option Includes lower priced brands 35% from incumbent brands Is this consistent with entry data? If not, modify model 2002 Cruise Line Merger: Introduction Carnival (largest) and Royal Caribbean (second largest) each bid for Princess (third largest) Capacity constraints and “perishable” service – big fixed costs, small marginal costs Key strategy is “revenue management” – Price to match uncertain demand to available capacity, i.e. to “fill the ships” Merger of Parking Lot Operators Central Parking acquired Allright Two largest parking lot operators in US Pricing: “Is lot full by 9am?” If “no,” then reduce price If “yes,” then raise price This profit calculus unchanged by merger No merger effect if lots are full But Justice Department opposed merger Asked for 74 lot divestitures in 18 cities Cruise Lines vs. Parking Lots Similar strategies: filling ships vs. filling lots There is no uncertainty about parking demand, but does that make a difference? Theories considered by FTC Fill-the-ship pricing is unaffected by merger No quantity effect, but low elasticity consumers pay more Were theories correct? Magnitude of effects? Conclusions Based on Formal Model of Revenue Management Two merger effects – Ownership effect raises price – Information sharing effect raises or lowers price But always increases quantity Both effects small and disappear as uncertainty decreases Confirms basic intuition from parking lot merger, i.e. firms price to fill the ships, and this profit calculus is unchanged by merger Differentiated Products Mergers What if we can’t estimate demand? Modelling choices and trade-offs Accounting for efficiencies Luke Froeb Owen Graduate School of Management Vanderbilt University Model Based Methodology Specify and estimate a model – Consumer model (demand) – Firm model (supply) Use model to simulate counterfactual scenario – Mergers, collusion, damages Example and Questions To “Test” Approach Logit demand curve – What about other forms? Price setting competition – What about product, promotion, placement? – What about auctions, quantity setting, vertical arrangements? Constant marginal cost – What about scale economies or capacity constraints? Static game – What about dynamic strategies? Unilateral merger counterfactual – What about coordinated effects? Critique of Market Share Screens With Differentiated Products Competition does not stop at market boundary Shares may be poor proxies for competitive effects No role for efficiencies How do you trade off a 10% marginal cost reduction against a 400 point change in HHI? Common Problem: Cannot Get Reliable Demand Estimate Relatively flexible functional forms often lead to nonsensical estimates – Goods are complements (when we know they are substitutes) – Inelastic demand (inconsistent with optimization) Data not up to task of estimating so many parameters Solution: Ask Less of Data by Making Intuitive Assumptions If one firm increases price, its rivals gain quantity in proportion to existing shares – Implies all goods are substitutes – Implies margins proportional to shares – Implies cross elasticities proportional to shares These restrictive forms require less data – Aggregate elasticity – One brand level elasticity or margin Replacing Market Share Screens Swedish beer merger Aggregate elasticity ≈ 1 Pripps margin ≈ 30% Significant industry average price increase 4% 1.2 Aggregat e Elast icit y 1.4 1 5% 0.8 6% 7% 0.6 2 2.5 3 3.5 Pripps 2.8% Demand Elasticity 4 Logit Model as a Screen WorldCom Sprint Merger Aggregate elasticity ≈ –1 WorldCom Margin ≈ 30% Relatively small price effects Using Logit Model as Screen (cont.) Rebuttable presumption starts dialogue – Show products are further apart than modeled – Show competition is more intense than modeled Requires different safe harbors – “Grant” parties a 5% MC reduction on each of their merging products Would have allowed WorldCom and Sprint, but not Swedish beer How Do you Incorporate Merger Specific Efficiencies? Simulate marginal cost reductions Both merging products get lower marginal cost Demonstrated merger specific cost reductions Price effect depends on inherent properties of assumed functional form for demand Compute marginal cost reductions that keep all prices at pre merger levels In general, 2X to 3X times computed price increase is enough Which Welfare Standard? Total vs. Consumer Welfare Do fixed costs count as such? Superior Propane: fixed cost savings but prices went up Gain in profits was higher than consumer welfare loss Can fixed cost reductions be passed on over time? Short run price increases vs. long run efficiencies Spatial Competition Grocery Store Merger Parking Lot Merger Luke Froeb Owen Graduate School of Management Vanderbilt University Geographic Differentiation Retail Sector is Consolidating In US, Wal-Mart, K-Mart, Target, Costco, and Sears account for 60 percent of general merchandise sales – General merchandise is 15 % of all retail sales Productivity advantage over smaller retailers – Economies of scale – Economies of purchasing – Economies of distribution Productivity Gains Associated with Industry Consolidation Retail Consolidation Also in Europe In EU, top 10 grocery stores forecast to increase share to 50 or 60% – In 2002, top 10 had 38% Wal-Mart entering Europe Policy Reaction to Retail Consolidation FTC challenged some retail mergers – Blocked Kroger and Winn-Dixie – Blocked Staples and Office Depot Competitive analysis based on increase in local (within city) horizontal market power – “standard” horizontal analysis Quantitative Horizontal Analysis: Benefit-Cost Analysis of Merger Goal: effect quantitative estimate of merger – Necessary to weigh efficiencies against loss of competition Two methodologies – “Natural” experiments, e.g. Staples and Office Depot – Model based simulations Natural Experiments: Staples and Office Depot Prices in two office superstore cities found to be 7% lower than in one office superstore city – Is this a good metaphor for merger? Pass-through rate (from cost to prices) was estimated to be 15% This implies that a 85% reduction in costs necessary to offset merger effect Is low pass through consistent with big merger effect? FTC successfully challenged merger Model Based Simulation Model current competition Estimate model parameters Simulate loss of competition using estimated parameters Unilateral competitive effect computed as difference between pre and postmerger Nash equilibria Model Based Simulation: Kroger and Winn Dixie Estimate “gravity” choice model – Survey density in Charlotte, NC – Dots represent grocery stores Choice depends on price, distance, and “noise” Premerger Equilibrium: Share of Kroger and Winn-Dixie Postmerger Equilibrium: Share of Kroger and Winn-Dixie Parking Lot Merger “Gravity” choice model Lots derive market power from location, capacity Higher prices if – Few nearby lots – Many nearby consumers – Small lot capacity Parking Lot Merger Model: Conclusions Constraints on merging lots attenuate merger effects by more than constraints on nonmerging ones amplify them Merger effects poorly approximated by shares in geographic market areas – No bright lines between “in” and “out” – Shares poor proxies for localized competition Justice Department erred when it asked for divestitures in 5 square block areas where the merging firms account for more than 35% Ignored role of constraints on merging lots Gravity Choice Models And Merger Effects Merger effects “depend” on – Location of consumers – Location and capacity of merging firms – Location and capacity of nonmerging firms – Cost of travel – Other factors affecting demand Weak generalization: small price effects if location only source of market power