Employment assistance for people with mental illness

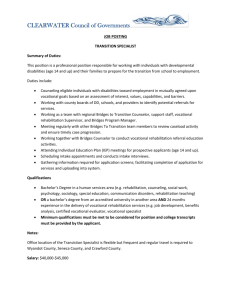

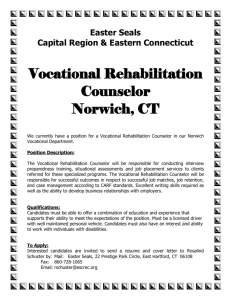

advertisement