Cas_271_Midterm Group5_South Korea

advertisement

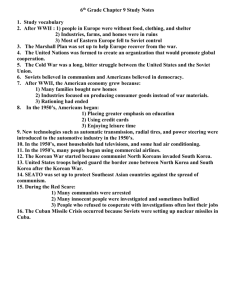

Emily Tweed, Zaine Shetayh, and Jordan Spechler Professor Ines Meyer-Hoess CAS 271 23 February 2015 South Korea and Communication Certain South Korean cultural factors, such as the social hierarchy, dictate the ways in which people from the country communicate. Social and cultural identities, value orientations, and the Korean language all reflect aspects of South Korean culture that can greatly influence communication, both intraculturally and interculturally. There are many different ways South Koreans converse in different situations, such as dining and meeting etiquette. Similar to many other cultures, the South Korean culture revolves a lot around respect. One interesting trait, for instance, is their consideration toward others. For example, it is inconsiderate to give someone an expensive gift if one knows that he or she cannot afford to reciprocate accordingly. Taking a look at the country’s history in relation to North Korea, North Korea is a lot more publicized than South Korea, but the two countries share a rich history that ties together their culture and their means of communication. Koreans share a common culture, but a sense of regionalism exists between Northerners and Southerners in terms of customs and perceived personality characteristics. Despite their similarities, they are neighbors with totally opposite views. This diminishes the Peace Imperative on whether they can coexist peacefully. South Korea is a democracy, whereas North Korea is a complete dictatorship. A lot of North Koreans travel to South Korea in hopes of freedom. The way South Koreans converse with the Northerners is very different depending on who one asks. South Korea has a more individualistic culture which deals with Cultural-Individual Dialectic. A lot of South Koreans sympathize with North Korean citizens instead of despising them and turning them away. The situation between the two countries revolves around politics, but emotion plays a big part when the citizens of each country converse with each other. North Korea and South Korea share a rich history that deals with the history/past-present/future dialectic. As stated above, not only do South Koreans sympathize with the North Koreans, but they also take them in, which the law allows them to do. The South Korean constitution states South Korea consists of the whole Korean peninsula. This means North Koreans have citizenship in South Korea. The South Korean government provides means of support for North Koreans when they arrive to South Korea, giving the immigrants money for housing and settling issues in general due to adjustment programs. South Korea is known to have a social hierarchy that is a factor in its people’s communication. There are four different social and cultural identities that mesh perfectly with the way that communication occurs in South Korea. These four identities are gender identity, age identities, class identity and personal identities. These identities are huge in seeing how South Koreans communicate with one another. Starting off with gender, it is crucial to understand that women are looked at as equals to men. This is key because women and men in the workplace treat each other the same. Men are not able to talk down to women. Women are just as likely to give directions, and men must listen and respond to women with whom they are communicating with the utmost respect. Communication between men and women will not create any animosity since they are all looked at as equal. Next, due to the fact that South Korea runs by a social hierarchy, another major social and cultural identity is age identity. South Koreans, like in many Asian countries, are all about respecting their elders. This is exactly what the social hierarchy is; it is all about position of power. Because of this, children and teens are taught from the day they are born that respecting their parents and grandparents is of the utmost importance. An example of this unspoken rule is that when one is receiving a present from an elder, it is customary to take the present with two hands and bow at the same time (“Korean Customs”). This is a sign of respect that goes beyond simply saying “thank you.” When different age groups are communicating, the only way any problems can occur is that if one does not respect his or her elders. Another key identity that applies to South Korean communication is class identity. This refers to the way people communicate based on how much money they have, what they wear, the job they have, etc. This fits right into the South Korean social hierarchy. For instance, if the employees and president of a company are out to a business dinner and drinks are being served, it is customary for the subordinates to look away when taking their drink in front of the president (“Korean Customs”). By doing this, they are showing respect to someone who is above them in the class system, particularly in terms of job rank, and by respecting this, no problems can occur while communicating between the classes. Lastly, personal identity is one that fits right into South Korean communication. This shows who people are based on outside influences. For example, when visiting South Korea, if one is on a bus, one would be showing a ton of respect by getting up and allowing an elder to have one’s seat. Every Korean would take notice and think you are a well-mannered guest in their country (“Korean Customs”). This nonverbal communication through outside influences shows why personal identity can lead to only mutual respect and understanding if done properly. Looking at value orientations, South Korean culture generally contrasts with most Western cultures. Firstly, with regards to time orientation, Koreans tend to be past-oriented. In other words, they acknowledge and value history and often apply it to the present (Martin and Nakayama 107). According to Young-Ok Lee in her paper “Perceptions of Time in Korean and English,” “differences in the concept of time-related values cause differences in the verbal and nonverbal communication patterns, which may lead to misunderstanding or even conflict” (Y. Lee 120). Koreans’ past time orientation is evidenced in their “leisureliness” about punctuality and “their respect for the oldness” of people and things (Y. Lee 120), particularly their respect for elders, which contributes directly to the social hierarchy. Thus, even something as seemingly simple and universal as time has the potential to bring about miscommunication. Next, like most East Asian cultures, South Korea is generally collectivistic; that is, the culture is group-oriented and “place[s] a great deal of importance on extended families and group loyalty” (Martin and Nakayama 104). Funerary rites and ancestor rituals are important aspects of life for many Koreans (K. Lee, 199-200), so even after death, the family group is important. This actually also relates to time orientation in valuing the past and, of course, to the social hierarchy in valuing and paying respects to the ancestors. A final value orientation that is important with regards to communication is uncertainty avoidance. In South Korea, there are both “[m]ore extensive rules” and “[m]ore formality” when it comes to interaction among people (Martin and Nakayama 108), so the country is generally high on the uncertainty avoidance scale. This emphasis on rules and formality is most obviously apparent in, again, the social hierarchy, which dictates how individuals should communicate based on their age, status, and/or relationship. This brings me to the fact that South Korea’s social hierarchy is also reflected in its language. The Korean language features a complex system of honorifics that is extremely important when it comes to being respectful. The word one uses can change—or rather, should change depending on the situation, particularly the person one is speaking to and/or about. Take, for instance, the simple speech act of “thank you.” One of the most commonly used Korean thank-you words is “고맙다” (gomapda), which seems simple enough. But that is merely the dictionary form, and one must choose the appropriate conjugation, or word ending, for the situation at hand. If one is speaking to a stranger, someone older, or someone of higher social or class standing, one might use the deferential and highly formal “고맙습니다” (gomapseumnida). If one is speaking to a close friend or significant other, one would most likely drop the honorifics and perhaps use “고마워” (gomawo). Notice how the ending changed. And those are only two of several different conjugational forms. Furthermore, verb and adjective conjugations are not the only aspect of Korean honorifics. There are honorific suffixes, honorific forms of pronouns and nouns, honorific subject markers: in short, the system is extensive. Clearly, Korean is a very high-context language; word choice is all important and individual words can carry much meaning, particularly with regard to the age, social status, and/or relationship of the people involved in a speech act. And because of this, miscommunication could be a greater possibility than in, say, English, a rather low-context language in which the overall picture is emphasized more and individual words carry less significant meaning on their own. As is plain to see, communication in South Korea is largely influenced by features of the culture, particularly the social hierarchy, and knowledge of these features is extremely important if one wishes to communicate effectively and without risk of exhibiting disrespect. In addition, one can see the two different global paths of North Korea and South Korea and how this divide has impacted each country respectively. Overall, the potential for conflict and misunderstanding due to these many differences speaks to the importance of intercultural learning and making an effort to better understand the intricacies of other cultures. It also demonstrates the value in cross-cultural inclusion, which can allow the interesting Korean culture to integrate with the myriad of other cultures on this pale blue dot that we humans call home. Works Cited "Korean Customs - Respect." ZKorean. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Feb. 2015. Lee, Kwang Kyu. "The Concept of Ancestors and Ancestor Worship in Korea." Asian Folklore Studies 43 (1984): 199-214. JSTOR. Web. 25 Feb. 2015. Lee, Young-Ok. "Perceptions of Time in Korean and English." Human Communication 12.1 (n.d.): 119-38. Web. 25 Feb. 2015. Martin, Judith N., and Thomas K. Nakayama. Intercultural Communication in Contexts. Sixth ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2007. Print. Tanaka, Hiroyuki. "North Korea: Understanding Migration to and from a Closed Country." Migrationpolicy.org. Migration Policy Institute, 07 Jan. 2008. Web. 21 Feb. 2015.