Stocks

advertisement

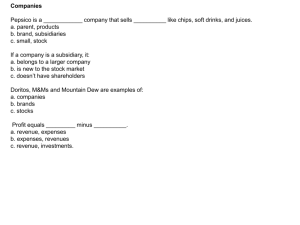

Navigating the Stock Market Stocks Stocks are a share in the ownership of a company. Stock represents ownership of a company’s assets and earnings. As you acquire more stock, your ownership in the company increases. Shares, equity, and stock all mean the same thing. Being an Owner Owning a company’s stock means that you are a part owners (shareholders) of a company. As such, you have a claim (based on the percentage of shares you own) to what the company owns. This means that you own some of the furniture, the trademarks, and the contracts of the company. Also, you are entitled to share in the company’s earnings as well as the voting rights as specified in the stock. Being an Owner (continued) There are 2 types of stock ownership: Preferred stock: dividends are paid to preferred stock holders first. Common stock: able to vote but are paid dividends last. Larger amount of shares are available. Dividend: Payments made to shareholders by corporations. When a company earns profit, the company can use the money to either re-invest in the business (retained earnings) or to give shareholders as dividends or share repurchase. Many corporations keep a portion of their profit and pay the remainder as a dividend. Dividend options: Corporations can pay dividends in the form of cash, stock or property. Most large profitable companies offer dividends to their stockholders. Their share prices might not move much, but the dividend they pay make up for this. Higher-growth companies typically don’t offer dividends because their profits are reinvested to help continue their higher than average growth. Stock symbols Stocks listed and traded on U.S. exchanges such as the NYSE have symbols with up to 3 letters. Nasdaq-listed stocks have 4 letter symbols. Examples: XOM: Exxon BAC: Bank of America AAPL: Apple GOOG: Google GE: General Electric Bid Price: When you are selling your shares of a stock, the bid price is what the buyer is willing to pay for your shares. This Bid Price offers you an exact price of how much you can sell your shares for. Ask Price: The Ask Price is the price at which a seller is willing to let go of her shares. More specifically, this is the price you will buy your stocks at. The PE Ratio provides a numeric representation of the value between the stock price and earnings. To derive the PE Ratio you divide the share price by the company’s Earnings Per Share. Example: Coca Cola’s (KO:NYSE) stock price (Price per Share): $66 Coca-Cola’s Earnings-per share (EPS): $5.26 Coca-Cola’s PE Ratio: $66 / $5.26 = 12.55 Pepsi’s (PEP:NYSE) stock price (Price per Share): $69 Pepsi’s Earnings-per share (EPS): $3.73 Pepsi’s PE Ratio: $69 / $3.73 = 18.50 From our calculations, we can see that Pepsi has a higher PE Ratio than Coca-Cola. How to interpret the P/E Ratio High P/E Ratio may mean: Market sentiment: An overly optimistic P/E Ratio can indicate the market expects big things from this company. The company has high growth possibilities. Lifecycle: The company could be entering into the Growth or Shake-Out stage of its lifecycle. Industry: Specific Industries have a certain level for the P/E Ratios. For example most technology companies have high P/E Ratios. Cover priced or over-bought: A high P/E Ratio can indicate a given stock is priced to high and ready for a correction. This means that it might be overvalued. Be sure to compare against industry norms. Low P/E Ratio may mean: Lack of confidence: A low P/E Ratio may indicate a lack of confidence in the future of the company. Lifecycle: The company could be in the Mature or Decline stage of its lifecycle. Industry: Specific Industries have a certain level for the P/E Ratios. For example most utility companies have low P/E Ratios. Sleeper: A low P/E Ratio might be a sleeper just waiting to be discovered. This means that it might be undervalued, and a perfect time to start buying the shares. Dividend Yield: A ratio showing how much a company pays in dividends each year relative to its share price. Assuming that the stock price does not change, the dividend yield is the only return on the stock holder’s investment. Dividend yield is a way to measure how much “bang for your buck” you are getting from your investment through dividends. Example: If two companies pay the same annual dividends of $1 per share per year, but company 1 stock sells at $20 while company 2 stock sells at $40, then company 1 has a dividend yield of 5% while company 2 is only yielding 2.5%. Assuming that all other factors are the same, an investor that is looking to add to his or her income would likely prefer company 1 stock over that of company 2 stock. Market Orders are an order to buy or sell a stock at the best available price. Generally, this type of order will be executed immediately. However, the price at which a market order will be executed is not guaranteed. It is important for investors to remember that the last-traded price is not necessarily the price at which a market order will be executed. In fast-moving markets, the price at which a market order will execute often deviates from the last-traded price or “real time” quote. Market orders Your market order is executed at the best price obtainable at the time the order is executed. In other words, with a market order the fact that the order will be filled is all but guaranteed (subject to the availability or liquidity of the stock), but the price at which it will be filled is not. The market is dynamic. Prices are changing continuously in the market as the minutes go by. Orders are executed with priority rules, delays in execution can occur due to market demand of a security, and in the meantime a market price can change as a result of investor demand and other factors. Large orders can also take longer to fill and can move the market (price and volume) for the stock, sometimes to your disadvantage. Limit orders In contrast to the market order, there is another type of order called a "limit order" that does guarantee the price but does not guarantee an execution. Limit orders require you to place a limit on the amount you are willing to pay to buy a stock or on the amount you are willing to accept to sell a stock. Naturally, you will accept more favorable prices if you can get them. Different types of orders allow you to be more specific about how you'd like your broker to fulfill your trades. When you place a stop or limit order, you are telling your broker that you don't want the market price (the current price at which a stock is trading), but that you want the stock price to move in a certain direction before your order is executed. With a stop order, your trade will be executed only when the security you want to buy or sell reaches a particular price (the stop price). Once the stock has reached this price, a stop order essentially becomes a market order and is filled. For instance, if you own stock ABC, which currently trades at $20, and you place a stop order to sell it at $15, your order will only be filled once stock ABC drops below $15. Also known as a "stop-loss order", this allows you to limit your losses. However, this type of order can also be used to guarantee profits. For example, assume that you bought stock XYZ at $10 per share and now the stock is trading at $20 per share. Placing a stop order at $15 will guarantee profits of approximately $5 per share, depending on how quickly the market order can be filled. Stop orders are particularly advantageous to investors who are unable to monitor their stocks for a period of time, and brokerages may even set these stop orders for no charge. Buy limit order example: THI is selling for $84 a share. You think the stock could decline in the short-term and then rebound strongly upward. So you place a limit order GTC (Good Till Canceled) to buy THI at $82. (Any price different from the current market price is said to be "away from the market”.) Now the broker/dealer's computers monitor your order and when the stock price hits $82 your buy limit order is executed at that specific price. If the stock price does not decline to $82, your limit order is not executed. Sell limit order example: You own Tim Hortons stock, which is trading at $84. You think the stock can still go higher. So you place a sell limit order at $88. When the stock price rises to $88, your limit order is executed, subject to there being enough demand for the stock at your specific price. If the stock price does not rise to $88, your limit order is not executed. Risks of limit orders: Limit orders give you more control over execution price, but control also comes with certain limitations that you should be aware of: i.e. you may miss owning or selling stock, depending on the circumstances. The stock may never reach your limit price and your limit order will not execute. For example, in the Sell Limit Order example above, if Tim Hortons only reached $87 and then started to fall, your limit order would not have executed and you'd still own the stock as its price drops. Fail to execute: Even if your stock reaches the limit price, your limit order may not execute if there are orders ahead of yours at the same limit price. The orders in line ahead of you must be filled first and there may not be enough stock available to fill your order when its turn comes. STOP ORDER: An order to buy or sell a stock when its price surpasses a particular point, thus ensuring a greater probability of achieving a predetermined entry or exit price, limiting the investor's loss or locking in his or her profit. Once the price surpasses the predefined entry/exit point, the stop order becomes a market order. TRAILING STOP: A stop order that can be set at a defined percentage away from a stock’s current market price. A trailing stop for a long position would be set below the stock’s current market price; for a short position, it would be set above the current price. A trailing stop is designed to protect gains by enabling a trade to remain open and continue to profit as long as the price is moving in the right direction, but closing the trade if the price changes direction by a specified percentage. Traders and investors who seek to limit potential losses can use several types of orders that can get them into and out of the market at times when they may not be able to place an order manually. Stop-loss and stop-limit orders are two such order types that can accomplish this. But it is critical to understand the difference. Stop Loss Orders There are two types of stop-loss orders: 1) Sell-stop orders protect long positions by triggering a market sell order if the price falls below a certain level. The underlying assumption behind this strategy is that if the price falls this far, it may continue to fall much further, so the loss is capped by selling at this price. Example: Frank owns 1,000 shares of ABC stock. He purchased the stock at $30 a share, and it has risen to $45 on rumors of a potential buyout. He wants to lock in a gain of at least $10 per share, so he places a sell-stop order at $41. If the stock drops back below this price, then the order will become a market order and get filled at the current market price, which may be more (or more likely less) than the stop-loss price of $41. In this case, Frank might get $41 for 500 shares and $40.50 for the rest. But he will get to keep most of his gain Stop-Limit Orders These orders are similar to stop-loss orders, but as their name states, there is a limit on the price at which they will execute. There are two prices specified in a stop-limit order; the stop price that will convert the order to a sell order, and the limit price. Instead of the order becoming a market order to sell, the sell order becomes a limit order that will only execute at the limit price or better. Of course, there is no guarantee that this order will be filled, especially if the stock price is rising or falling rapidly. Stop-limit orders are sometimes used because if the price of the stock or other security falls below the limit, then the investor does not want to sell and is willing to wait for the price to rise back to the limit price. Example: Frank’s ABC stock never drops to the stop-loss price, but it continues to rise and eventually reaches $50 a share. He cancels his stop-loss order at $41 and puts in a stop limit order at $47 with a limit of $45. If the stock price falls below $47, then the order becomes a live sell-limit order. If the stock price falls below $45 before Frank’s order is filled, then the order will remain unfilled until the price climbs back to $45. Many investors will cancel their limit orders if the stock price falls below the limit price, because they placed them solely to limit their loss when the price was dropping. Since they missed their chance to get out, they will then simply wait for the price to go back up and may not wish to sell at that limit price at that point, because the stock may continue to rise. If Frank could not get out at $45 or better and the stock price falls back to $40, then he may be wise to cancel the order, because if it rises back to $45, it may keep going. As with buy-stop-loss orders, buy-stop-limit orders are used for short sales where the investor is willing to risk waiting for the price to come back down if the purchase is not made at the limit price or better.