here - Melbourne Law School

advertisement

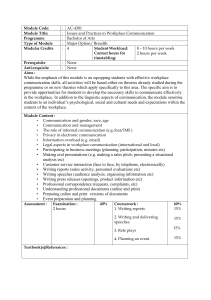

The Ambiguities of Workplace Co-operation Professor Mark Bray The University of Newcastle Public Lecture sponsored by the Fair Work Commission & The University of Melbourne Law School 24 May 2013 Overview 1. The importance of workplace cooperation 2. Ambiguity in the meaning of workplace cooperation 3. The Pluralist Vision 4. The Unitarist Vision 5. Conclusions 6. References 2 1. The importance of co-operation • Almost everyone thinks co-operation in the workplace is a good idea! 3 1. The importance of co-operation (cont.) 4 National laws and systems of ER Workplace co-operation Governments of both political persuasions see co-operation as a central goal of national laws: • Fair Work Act 2009: → S. 3 makes ‘co-operative and productive workplaces’ an object of the Act → S. 577 and S. 682 as well • Workplace Relations Amendment (Work Choices) Act 2005: → S. 3 retained ‘co-operative workplace relations’ the principal object of the Act • Workplace Relations Act 1996: → S. 3 “The principal object of this Act is to provide a framework for co-operative workplace relations” 1. The importance of co-operation (cont.) National laws and systems of ER National economic performance Workplace co-operation Organisational performance • These legislative provisions reflect the views of the political leaders who created them • These politicians also frequently claim that workplace cooperation ultimately produces both: → improved organisational performance (including productivity), and → better national economic outcomes 5 1. The importance of co-operation (cont.) National laws and systems of ER National economic performance Workplace co-operation Organisational performance • Much research supports their views ie. there is a positive relationship between workplace co-operation and organisational performance, ... although I do not have the time to detail this research today • But any causal link with national economic outcomes is less well proven in research ... but it remains an article of faith 6 1. The importance of co-operation (cont.) National laws and systems of ER National economic performance Workplace co-operation Organisational performance • Conclusion? • Co-operation in the workplace is desirable and important • We need to understand what workplace co-operation means ... and how it might be linked to public policy • This is my ambition today! 7 2. The ambiguous meaning of workplace co-operation • One of the challenges is that “workplace co-operation” is an ambiguous concept • It means different things to different people • How do we understand the many meanings of cooperation? 8 2. Ambiguous meaning (cont.) 9 • The Australian Concise Oxford Dictionary defines ‘co-operation’ as: “working together to the same end” • To embellish a little, on the basis of common sense: → “working together” is both a process and an end product → “working together” is about “relationships” involving “mutuality” and “reciprocity” → “the same end” implies some consensus about a common interest or goal → both the process and the end imply choice and willingness, ... something positive and active that goes beyond mere compliance 2. Ambiguous meaning (cont.) 10 • However, many unanswered questions, including: → Who is working together? → What is the “same end”? → Who determines what the “same end” is? → How does working together work? • We also need to focus more specifically on co-operation in the workplace 2. Ambiguous meaning (cont.) 11 • Long history of scholarship on “workplace co-operation” • Although much of it uses different (but related) concepts: → Industrial goodwill → Industrial peace → Industrial relations climate → Joint consultation → High performance workplaces → Collaboration → High involvement workplaces → The mutual gains enterprise → Union-management partnerships → Industrial harmony • All of these concepts are relevant and deserve attention, but not today! • My (very selective) account: → is informed by (but does not systematically review) this scholarship, → keeps an eye on its relevance to recent Australian public policy 2. Ambiguous meaning (cont.) 12 • Two different meanings of workplace cooperation, distinguished by: → the values that underlie different approaches to workplace cooperation → the role they give to employee representation in workplace cooperation • I will refer to these two approaches to workplace cooperation as: → The Pluralist Vision: Co-operation marked by independent employee representation (usually unions) based on pluralist values → The Unitarist Vision: Co-operation conceived as purely involving direct relationships between managers and employees, based on unitarist values • Analytically, the “visions” are ideal types ... ie. extreme simplifications designed to characterise Overview 1. The importance of workplace cooperation 2. Ambiguity in the meaning of workplace cooperation 3. The Pluralist Vision – – – – Underlying values Definition Implications for Public Policy Application to Australia 4. Co-operation based on direct management-employee relations – – – – Underlying values Definition Implications for Public Policy Application to Australia 5. Conclusions 6. References 13 3. The Pluralist Vision of Workplace Co-operation 14 • Ironically perhaps, the best accounts of the pluralist vision come from the USA (eg. Commons 1919, Golden & Parker 1955, Walton & McKersie 1965, Kochan & Osterman 1994, Kochan et al. 2009) • Less of a scholarly tradition in Britain, ... but the Blair government’s “union-management partnerships” generated valuable research (ie. Ackers & Payne 1998, Oxenbridge & Brown 2002, Stuart & Martinez Lucio 2005, Stuart et al. 2011; see also Mitchell & O’Donnell 2008) • I will come back to evidence of the practice and research in Australia 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) UNDERLYING VALUES • The concept of “pluralism” will be familiar to many in the audience • It is most famously associated with the British scholar Alan Fox (1966), ... and more recently, John Budd and others (eg. Budd & Bhave 2008) • Key elements of the pluralist “frame of reference” include: → Organisations comprise individuals and groups with competing and sometimes contradictory interests → Each group and its interests are considered legitimate and respected → Competing interests can sometimes produce conflict, ... which must be managed through appropriate procedural mechanisms or governance arrangements → Common interests and cooperation can be established and developed, ... but they require joint decision making and active consent by all groups 15 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) DEFINITIONS • I could find no explicit pluralist definition of “workplace cooperation” • I’ll try to bring together contributions on alternate concepts • Golden (1955) provides a starting point when he defines “industrial peace” as: “the product of the relationship between two organised groups – industrial management and organised labour – in which both coexist, with each retaining its institutional sovereignty, working together in reasonable harmony in a climate of mutual respect and confidence.” (p. 8) • Strengths: → “institutional sovereignty” recognises competing interests, acceptance of separation and the need for organisational security on both sides → “reasonable harmony” is a measured concept that recognises that “working together” may have limits because of potentially conflicting interests → “mutual respect and confidence” reflects both reciprocity and the need for tolerance of the other side 16 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) DEFINITIONS (cont.) • Weaknesses: → Conflates cooperation as a process and an end product → While later recognising that “peace is something more than the mere absence of conflict” (p. 7), ... he does not capture the more positive, active engagement essential in “cooperation” → The pre-occupation with “two organised groups” assumes an exact coincidence of interest between unions and workers/members ... this over-simplifies the complex range of interests in workplaces 17 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) DEFINITIONS (cont.) • Walton & McKersie’s (1965) account of “integrative bargaining” is useful, … although it focuses exclusively on the process of cooperation • They distinguish between: → “integrative bargaining” (later became “interest-based negotiation”, IBN) → “traditional”, “distributive” or “adversarial” bargaining. • The process of IBN focuses on the common interests in a pluralist relationship: → identify common problems → explore the interests that underlie them → develop joint solutions • “Traditional bargaining” is also pluralist, but: → focuses on distributional issues → involves fixed claims and defending positions → employs more adversarial bargaining process See Macneil and Bray (2013) 18 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) DEFINITIONS (cont.) Later American writings focus more on the end product than the process … by using the term “mutual gains” (Kochan & Osterman 1994): “We use the term ‘mutual gains’ because it conveys a key message: achieving and sustaining competitive advantage from human resources require strong support from multiple stakeholders in an organisation. Employees must commit their energies to meeting the economic objectives of the enterprise. In return, owners (shareholders) must share the economic returns with employees and invest those returns in ways that promote the long-run security of the work force. And everyone involved in decision making must behave in ways that build and maintain the trust and support of the work force.” (p. 46) 19 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) DEFINITIONS (cont.) Employee representation? • Pluralists consistently emphasise unions. Why? • Freeman & Medoff’s (1984) “two faces” of unionism suggests: → Collective Voice Face: o o o Unions provide an independent and collective mechanism by which employees can voice their opinions to managers Allows employees to be less guarded in their feedback to management Potentially valuable role for external union officials → Power/Monopoly Face: o Without the power of a union, employees may not be taken seriously by managers o Union power provides some protection in the distribution of economic benefits 20 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) DEFINITIONS (cont.) • This pluralist approach’s reliance on unions raises other issues: → Unions must accurately representing the views of employees/members → The acknowledgement and accommodation of different groups on the employee side: o Employees o Workplace union representatives o Union officials working outside the workplace • Is it possible for non-union forms of employee representation to perform the same role in pluralist workplace cooperation? → maybe, but they must be independent of management → and they have some power vis-à-vis management → eg. statutory works councils 21 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) DEFINITIONS (cont.) Conclusion? • My summary of the pluralist vision of workplace cooperation sees it as: “... a relationship in which managers work willingly with employees and their independent representatives in a process that supports the creation of jointly agreed goals and solutions. They do this through governance structures that recognise the separate but inter-dependent interests of the constituent groups. The outcome is the achievement of mutual gains, benefiting all constituent groups.” 22 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) IMPLICATIONS FOR PUBLIC POLICY How do governments promote the pluralist vision of cooperation? • It is not possible to mandate or compel cooperation, … because of its voluntary nature (see Mitchell & O’Donnell 2008, pp. 103-4) • “Hard regulation”: The law used to establish employee rights and compel employers to ... inform, discuss, consult or bargain with employees and/or their unions, ... based on an assumption this will encourage greater cooperation • “Soft regulation”: Non-binding initiatives used to encourage changes in behaviour including: → financial incentives and grants; → the provision of training, expert information and advice; → demonstrations of “best practice” (eg. Stuart et al. 2011; Macneil et al. 2011). 23 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) APPLICATION TO AUSTRALIA Have Australian governments tried to promote the pluralist vision of workplace cooperation? Conservative governments: No → The Howard governments (1996 – 2007) were anti-union and saw little value in promoting union-management cooperation → The May 2013 Abbott/Abetz Workplace Relations policy statement says nothing about cooperation, with only one exception → The exception is a point about “harmonious” productivity bargaining, ... which seems more about productivity than cooperation • The answer is more complicated for Labor governments 24 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) APPLICATION TO AUSTRALIA Labor government (1983 – 1996): Yes • “Co-operation” was a central rhetorical theme under the Accord, .. especially during the period that Bob Hawke was Prime Minister • It was “pluralist” because it recognised competing interests of unions and employers ... and sought to engage unions and employers in decision making • It was, however, mostly centralised cooperation before 1986, ... focusing above the workplace on national policy making • One exception: decisions of tribunals to oblige employers to consult with employees and unions in the event of technological change and/or redundancies (Markey 1987) 25 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) APPLICATION TO AUSTRALIA Labor government (1983 – 1996) continued...: • Workplace cooperation became a stronger theme after 1986, ... with several mechanisms used to promote it: → “Managed decentralism” in wage policy: ... wage increases were dependent on managers and unions to bargaining over ‘second tier’, ‘award restructuring’ and then ‘structural efficiency’ (Bray 1994, Mitchell & O’Donnell 2008) → The Keating govt’s Industrial Relations Reform Act (ss. 170MC(1)(d) and 170NC(1)(f)): ... insisted that all EBAs include provisions about consultation between employers and unions on “efficiency and productivity” within the enterprise (Mitchell et al 1997) → Did “good faith bargaining” under the IRR Act promote of cooperation? (Patmore 2010, pp. 85-6) 26 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Labor government (1983 – 1996) continued...: • • • Another feature of the labour laws of the time was their collectivism All the legal supports for cooperation relied exclusively on unions for employee representation (eg. Bray & Macneil 2011, Bray & Stewart forthcoming) The exception was non-union collective agreements (EFAs), ... which were rarely used • Labor governments also used “soft regulation” (Macneil et al 2011): → The Hawke/Keating government’s Best Practice Program during 1990s (see. Rimmer et al. 1996) → This again promoted unions as the mechanisms for employee representation 27 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Labor government (1983 – 1996) continued...: • In summary, the Hawke and Keating Labor governments: → adopted pluralist visions of cooperation, → promoted unions as a largely uncontested form of employee representation, and → provided both “hard” and “soft” mechanisms to promote cooperation 28 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Labor governments (2007 – 2013): Maybe • Key Labor politicians advocate cooperation • Then-Minister Julia Gillard: “In the Government’s view, we simply have to move beyond the destructive conflictbased model of workplace relations that was Work Choices and instead build a productive new workplace relations system based on promoting consultation and cooperation at the enterprise level.” (Gillard 2008) • Minister Bill Shorten: “What we need is no nonsense leadership in the workplace from employers and employees. Unions can and do promote productivity and have a big role to play in building productive workplaces. It starts with cooperation... We need to move away from the purely transactional model of workplace relations and to a much more collaborative approach. Valuing the contribution that employees have to make is an obvious starting point for improving workplace productivity.” (Shorten 2012) 29 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) 30 Labor governments (2007 – 2013): • Cooperation became an object of the Fair Work Act, ... but there are few mechanisms by which this is promoted: → Consultation and dispute resolution clauses back in awards and EAs, ... although now rights lie with employees without independent union rights → FW Commission obliged to perform its functions in a manner that “promotes harmonious and cooperative workplace relations” (s. 577) → FW Ombudsman obliged to perform functions in a manner that “promotes harmonious, productive and cooperative workplace relations” (s. 682) • Both the FWC and FWO are trying, but they have little legislative support • This is, in Forsyth & Smart’s (2009: 142-3) words, a “lost opportunity” 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Labor governments (2007 – 2013)… cont.: • Is “good faith bargaining” designed to promote cooperation? • Troy Sarina (2013) says yes: “Collective bargaining under Fair Work [was] modeled on a mutual gains or ‘win-win’ approach to bargaining.” (p. 404; also 398, 405, 406, 409, 414, 415) • I disagree: → “Good faith bargaining” advances traditional, adversarial bargaining → It is about guaranteeing basic rights for employees to be heard by their employer → These rights are “necessary” but not “sufficient” for cooperation → Pluralist cooperation requires more active and positive participation by both parties 31 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Labor governments (2007 – 2013)… cont.: • Unions are also much more vulnerable under these Labor governments • After more than a decade of hostility from the Coalition government, the FW Act gave some renewed support ... but not much (eg. Cooper & Ellem 2011, Bray & Macneil 2011, Bray & Stewart forthcoming) • In the absence of organisational security, can unions be expected to embrace workplace cooperation? 32 3. The Pluralist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Labor governments (2007 – 2013)... cont: • Conclusion? • The current Labor government may adhere to a pluralist vision of cooperation, but: → the absence of implementation mechanisms in the legislation reveals little about how cooperation is to be promoted → cooperation is mostly conceived as between employees and employers → the limited recognition of unions (ie. other than as the bargaining representatives of employees) creates organisational vulnerability 33 Overview 1. The importance of workplace co-operation 2. Ambiguity in the meaning of workplace co-operation 3. The Pluralist Vision – – – – Underlying values Definition Critics Application to Australia 4. The Unitarist Vision – – – – Underlying values Definition Implications for public policy Application to Australia 5. Conclusions 6. References 34 4. The Unitarist Vision of Workplace Co-operation • A long history in management theory from the USA and Britain, … from Scientific Management through Human Relations to ‘soft’ HRM (Klare 1988, Keenoy 2013) • The most recent version in both countries focuses on “employee engagement” • The term “employee engagement” first emerged about 20 years ago and has quickly become commonplace (Macey & Schneider 2008) “‘Employee engagement’ is now a vital and everyday part of the vocabulary of human resource management... The term... now routinely pervades the discourse of HRM across the English-speaking world, yet it was virtually unheard of a decade or so ago.” (Arrowsmith & Parker 2013) • Its popularity promoted by the Conservative government in Britain (see MacLeod and Clarke 2009) 35 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) UNDERLYING VALUES • Rests unambiguously on what Fox (1969) and Budd & Bhave (2008) called “unitarist” values • Key elements of unitarism include: → Organisations are unitary bodies in which employees and managers share a common interest represented by the organisational goals → There is a single source of authority; namely, management → Conflict is illegitimate and occurs only if: o management fails to lead effectively, or o external influences enter the organisation and disrupt the natural harmony between managers and employees → The realisation of common interests and cooperation will flow naturally from effective leadership by management 36 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) DEFINITION • There is still great diversity in the meaning attributed to employee engagement (eg. Macey & Schneider 2008, Keenoy 2013, Arrowsmith & Parker 2013) • Two components, often conflated: → “Employee engagement” as an outcome: “Engagement is above and beyond simple satisfaction with the employment arrangement or basic loyalty to the employer... Engagement, in contrast, is about passion and commitment – the willingness to invest oneself and expend one’s discretionary effort to help the employer succeed.” (Erickson cited in Macey & Schneider 2008, p. 7) → “Direct engagement” is more the process by which management deliver policies and practices which produce engaged employees “Engagement is about creating opportunities for employees to connect with their colleagues, managers and wider organisation. It is about creating an environment where employees are motivated to want to connect with their work and really care about doing a good job…” (MacLeod Report cited in Keenoy 2013) 37 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) DEFINITION (cont.) • As a form of “cooperation”, then, employee engagement: → focuses mostly on employees responding positively [ie. with cooperative attitudes and behaviour] → ... to the leadership of managers and the organisational policies and practices they implement 38 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) DEFINITION (cont.) • This leadership comprises both: → the personal attitudes and actions of the managers, and → the policies and practices of the enterprise • The relevant policies and practices are broadly those associated with sophisticated HRM, ... ranging from effective recruitment and selection of employees ... to performance management and employee development • By explicit statement or by omission, the exclusion of “third parties” is clear, ... allowing management to deal directly with employees 39 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) DEFINITION (cont.) • Employee voice mechanisms include: → → → → → Employee surveys Teams Performance management Consultation committees Informal one-on-one discussions with managers • “Teams” and “consultation committees” can give employees genuine decision-making power • But the other voice mechanisms focus on employees providing managers with the information they need to make better decisions, ... which will improve the performance of the enterprise, and ... reinforce the engagement of employees 40 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) IMPLICATIONS FOR PUBLIC POLICY Some very simple implications for governments: → If they are left alone to deal directly with each other, … managers and employees will naturally work cooperatively → … because managers will provide the appropriate leadership, and → “Third parties” (ie. unions and tribunals) must be excluded from the workplace Government therefore should use: → “hard regulation” (ie. the law) to exclude “third parties”, → and possibly “soft regulation” to promote appropriate leadership by managers 41 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) APPLICATION TO AUSTRALIA • Cooperation through direct engagement has been promoted in Australia since the 1990s by: → managers of individual companies (eg. Rio Tinto, BHP) → employer associations (eg. BCA, AMMA) → Coalition politicians (eg. John Howard, Peter Reith) • Arguably, the Coalition was inspired by this approach in both: → the 1996 Workplace Relations Act and → the 2005 Work Choices amendments • Let me briefly discuss some examples 42 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Australian Mines & Metals Association (AMMA): • AMMA has advocated direct engagement for nearly two decades • AMMA’s (2007) “Employee engagement – A lifetime of opportunity” is an unusually extended exposition of the concept • The underlying notion of the enterprise is clearly unitarist: “...the essence of a successful work organisation is its ability to operate systems which allow people who are otherwise unrelated to come together to achieve its goals...” (p. 31) • The definition of “employee engagement” embodies the conflation of end product and process: “Engaged employees willingly work to the best of their capability in the interests of the organisation and are encouraged to do so through the leadership, structure and systems of the organisation.” 43 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Australian Mines & Metals Association (AMMA)… continued: • Clear aims: “This report contends that improving and maintaining organisational effectiveness is dependent on the level of employee engagement in the workplace. A high level of engagement can be achieved through the leadership, structure and systems. If an organisation actively commits to employee engagement as a means of lifting its business performance, it cannot delegate the work involved to a third party.” (p. 9) • Need to isolate the enterprise from external influences or “third parties” (ie. unions and tribunals) • “Trust” between employees and managers is vital and flows from: “the personal integrity, behaviour and values of individuals, especially the leaders of the organisation.” (p. 30; see also p. 31) 44 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Australian Mines & Metals Association (AMMA)… continued: • By far the most important organisational policy/practice, is Performance Management Systems, which: “... ensure that each employee is clear on: the work expected in the role; how the role fits in to the wider purpose of the business; how they are performing in the role; and how they can improve their performance.” (p. 326 see also pp. 33 & 34) • Employee voice is not mentioned at all, ... only brief or superficial references to: → the importance of “communication”; → the personal involvement of site managers in negotiating individual contracts (p. 32); and → “building internal fair treatment systems to resolve individual concerns without recourse to third parties”. (p. 27) 45 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Coalition governments (1996 – 2007): • Without using the “direct engagement” language, PM Howard and his Ministers supported the Unitarist Vision • The debate surrounding the introduction of the 1996 WR Act revealed strong support for cooperation in the workplace: “This policy is about ensuring that the focus of industrial relations is where it belongs – at the level of the individual enterprise where employers and employees can see clearly that they have a common interest in the success of the enterprise.” (Reith 1996: 1) • Within the enterprise, “third parties” were considered unnecessary: “The bill rejects the highly paternalistic presumption that has underpinned the industrial relations system of this country for too long – that employees are not only incapable of protecting their own interests, but even of understanding them, without the compulsory involvement of unions and industrial tribunals.” (Reith 23/5/96) 46 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Coalition governments (1996 – 2007)...cont: • The Treasurer even more explicitly articulated the Unitarist Vision: “We say to them there is the opportunity for cooperation and consensus in the workplace... We also say to those in the work force that there is an opportunity to build that consensus and come to that agreement with a new system of industrial relations which can become the model for cooperation and which can allow the opportunity, free of third-party intervention, for employers and employees to agree.” (Costello 1/5/1996) • In July 2005, Prime Minister Howard summed up the aims of his government’s reforms as changing: “... the culture of the remote, adversarial and legalistic way employment relations were handled in the past”, replacing it with a system in which workers “grasp that high wages and good conditions in today’s economy are bound up with the productivity and success of their workplace” and ongoing productivity growth turns on “a continuous process of cooperation and commitment to implementing change”. (cited in Mitchell & O’Donnell 2008, p. 113) 47 4. The Unitarist Vision (cont.) AUSTRALIA (cont.) Coalition governments (1996 – 2007)...cont: • The “hard” regulatory changes introduced by the Howard government are well known, aimed at (see Mitchell et al. 2010): → Reducing the role of unions → Sidelining the industrial tribunals → Promoting individual contracts between employers and employees • Mitchell & O’Donnell (2008) summed them up by arguing that: “...the Liberal government... did little to support the rhetoric [of cooperation], apart from dismantling or subduing almost all the legal institutions and legal rights which supported the adversarial model historically” (p. 113) • One minor form of “soft regulation” was the promotion of private “alternative dispute resolution” agents ... as competitors to the industrial tribunals ... in assisting employers to resolve employment disputes internally (Reith 1998, Forbes-Mewett et al. 2005) 48 6. Conclusions • Co-operation in the workplace is desirable and important • If public policy is to be committed to promoting workplace cooperation, we must understand it better • A first step is to clarify the competing meanings of this ambiguous concept • The two visions of co-operation reviewed in this lecture embody very different: → Value systems → Approaches to employee • I hope I have shown how recognising these two visions helps to better understand Australian public policy 49 6. Conclusions (cont.) • My examples, however, have mostly been historical • I’ll finish with a current matter of public policy where the issues raised in this lecture are vital: → the Centre for Workplace Leadership proposed by Minister Bill Shorten • In September 2012, the Minister proposed the establishment of a such a Centre, funded with $12 million over four years (Shorten 2012b) • The focus of the Centre is to be the “leadership, workplace culture and management practices” required to improve productivity • The role of the Centre includes training and education, research and public advocacy 50 6. Conclusions (cont.) • This Centre can interpreted as “soft regulation”, … aimed at encouraging the growth of workplace practices conducive to improved productivity, … including cooperation between employers and employees • My question is: → Which vision of cooperation will drive this activities of this Centre? • The answer will affect: → Whose leadership is to be developed, and → The model of leadership to be advanced → The types of workplaces the government is promoting 51 6. Conclusions (cont.) • The future direction of the Centre for Workplace Leadership is just another example of … how recognising the ambiguities of workplace cooperation … helps us to better understand the trajectory of Australian public policy 52 7. References Acknowledgement: 53 Thanks for Dr Johanna Macneil for sharing so generously her ideas and feedback. Ackers, P., and Payne, J. (1998), ‘British Trade Unions and Social Partnership: Rhetoric, Reality and Strategy,’ International Journal of Human Resource Management, 9 (3), 529–549. AMMA (2007) “Employee engagement – A lifetime of opportunity, September: http://www.amma.org.au/library/paperspublications/376-paper-employee-engagement-a-lifetime-of-opportunity Arrowsmith, J. & Parker, J. (2013) ‘The meaning of “employee engagement” for the values and roles of the HRM function’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, forthcoming. Bray, M. (1994) ‘Unions, the Accord and Economic Restructuring’ in J. Brett et al. (eds), Developments in Australian Politics, Macmillan, Melbourne, pp. 259-76. Bray, M. and Macneil, J. (2011) ‘‘Individualism, Collectivism, and the Case of Awards in Australian Employment Relations’, Journal of Industrial Relations, 53 (2), April 2011, pp. 149-68 Bray, M. and Stewart, A. (2013) ‘From the Arbitration System to the Fair Work Act: The Changing Approach in Australia to Voice and Representation at Work’, Adelaide Law Review, forthcoming. Budd, J and Bhave, D (2008) “Values, Ideologies, and Frames of Reference in Industrial Relations,” in Paul Blyton et al. (eds.), Sage Handbook of Industrial Relations. London: Sage. pp. 92-112) Business Council of Australia (2009) ‘Embedding Workplace Collaboration – Preventing Disputes’, June: www.bca.com.au/UserFiles/Embedding_Workplace_Collaboration_Preventing_Disputes_FINAL_9.8.2009%283%29.pdf Commons, J. (1919) Industrial Goodwill, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. Cooper, R. and Ellem, B. (2011) ‘Trade Unions and Collective Bargaining’ in M. Baird, K. Hancock and J. Isaac (eds), Work and Employment Relations, Federation Press, Sydney, pp. 34-50 Forsyth, A and Smart, H (2009) Third Party Intervention Reconsidered: Promoting Cooperative Workplace Relations in the New “Fair Work” System, Australian Journal of Labour Law, 22: 117-46. Forbes-Mewett, H., Griffin, G., Griffin, J. and McKenzie, D. (2005) ‘The Role and Usage of Conciliation and Mediation in Dispute Resolution in the Australian Industrial Relations Commission’, Australian Bulletin of Labour, 31 (2), pp. 171-89. 7. References (cont.) 54 Fox, A. (1966) ‘Industrial Sociology and Industrial Relations’, Royal Commission on Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations Research Paper 2, HMGO, London. Freeman, R. & Medoff, J. (1984) What Do Unions Do?, Basic Books, New York. Gillard, The Hon J (2008) ‘Speech to the RSL and Services Clubs National Conference’, 22 July Golden, C. & Parker, V. (eds) (1955) Causes of Industrial Peace under Collective Bargaining, New York: Harper & Brothers. Golden (1955) ‘Introduction’ in Golden, C. & Parker, V. (eds) (1955) Causes of Industrial Peace under Collective Bargaining, New York: Harper & Brothers Keenoy, T. (2013) Engagement: a Murmuration of Objects? Unpublished manuscript, Cardiff. Klare, K. (1988) ‘The Labor-Management Cooperation Debate: A Workplace Democracy Perspective’, Harvard Civil RightsCivil Liberties Law Review, 23, pp. 39-83. Kochan, T, and Osterman, P (1994). The Mutual Gains Enterprise: Forging a winning partnership among labor, management and government. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Kochan, T., Eaton, A., McKersie, R. & Adler, P. (2009) Healing Together: The Labor-Management Partnership at Kaiser Permanente, ILR Press, Ithaca. Macey, W. and Schneider, B. (2008) ‘The meaning of employee engagement’. Industrial and Organisational Psychology 1:330 MacLeod, D. and Clarke, N. (2009) Engaging for Success: Enhancing Performance through Employee Engagement. A report to Government. London: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills Macneil, J and Bray, M (2013, forthcoming). Third Party Facilitators in Interest-Based Negotiation, Journal of Industrial Relations, 55 (5), November. Macneil, J., Haworth, N. & Rasmussen, E. (2011) ‘Addressing the productivity challenge? Government-sponsored partnership programs in Australia and New Zealand’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22 (18), November: 3813–3829 Markey Ray (1987) ‘Trade unions, New Technology and Industrial Democracy in Australia, Prometheus: Critical Studies in Innovation, 5 (1), pp. 124-145. 7. References (cont.) 55 Mitchell, R. & O’Donnell, A. (2007) ‘What is Labour Law Doing About “Partnership at Work”? British and Australian Developments Compared’ in S. Marshall et al (eds) Varieties of Capitalism, Corporate Governance and Employees, Melbourne University Publishing, Melbourne. Mitchell, R., Taft, D., Forsyth, A., Gahan, P. & Sutherland, C. (2010) ‘Assessing the Impact of Employment Legislation: The Coalition Government’s Labour Law Program 1996–2007’, Australian Journal of Labour Law, Vol. 23, pp. 274-301. Oxenbridge, S. & Brown, W. (2002) ‘The two faces of partnership and cooperative employer/trade union relationships’, Employee Relations, 24 (3), pp. 262-77. Patmore, G. (2010) ‘A Legal Perspective on Employee Participation’ in A. Wilkinson et al. (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Participation in Organisations, OUP, Oxford. Reith, The Hon P. (1998) Approaches to dispute resolution: A role for mediation?, Ministerial Discussion Paper, August, Department of Workplace Relations & Small Business, Canberra. Rees et al 2013 Rimmer, M, Macneil, J, Chenhall, R, Langfield-Smith, K and Watts, L (1996) Reinventing Competitiveness: Achieving Best Practice in Australia. Melbourne: Pitman Publishing. Sarina, T. (2013) ‘The Challenges of a Representation Gap: Australian Experiments in Promoting Industrial Citizenship’, Industrial Relations, 52 (S1), January, pp. 397-418. Shorten, The Hon B (2012a) Shorten, The Hon B (2012b) Centre for Workplace Leadership Media Release, 14 October: http://ministers.deewr.gov.au/shorten/centre-workplace-leadership Stuart, M. & Martinez Lucio, M. (eds) (2005) Partnership and Modernisation in Employment Relations, Routledge, London. Stuart, M., Martinez Lucio, M. & Robinson, A. (2011) ‘”Soft Regulation” and the modernisation of employment relations under the British Labour Government (1997-2010): partnership, facilitation and trade union change’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22 (18): pp. 3794-3812. Walton, R and McKersie, R (1965) A Behavioral Theory of Labor Negotiations: An analysis of a social interaction system. New York: McGraw-Hill Company