Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative

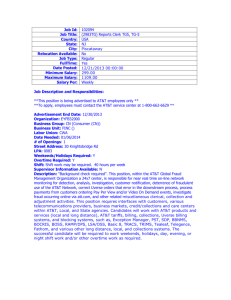

advertisement