Chapter 1: Statistics

advertisement

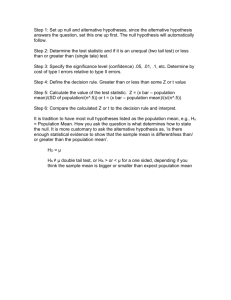

Chapter 8: Introduction to Statistical Inferences Level of Confidence 1 Maximum Error E E z ( / 2) n Sample Size n Chapter Goals • Learn the basic concepts of estimation and hypothesis testing. • Consider questions about a population mean using two methods that assume the population standard deviation is known. • Consider: what value or interval of values can we use to estimate a population mean? • Consider: is there evidence to suggest the hypothesized mean is incorrect? 8.1: The Nature of Estimation • Discuss estimation more precisely. • What makes a statistic good? • Assume the population standard deviation, , is known throughout this chapter. • Concentrate on learning the procedures for making statistical inferences about a population mean m. Point Estimate for a Parameter: The value of the corresponding statistic. Example: x 14.7 is a point estimate (single number value) for the mean m of the sampled population. Problem: How good is the point estimate? Is it high? Or low? Would another sample yield the same result? Note: The quality of an estimation procedure is enhanced if the sample statistic is both less variable and unbiased. Unbiased Statistic: A sample statistic whose sampling distribution has a mean value equal to the value of the population parameter being estimated. A statistic that is not unbiased is a biased statistic. Example: The figures on the next slide illustrate the concept of being unbiased and the effect of variability on a point estimate. Assume A is the parameter being estimated. Negative bias Under estimate High variability A Unbiased On target estimate A Positive bias Over estimate Low variability A Note: 1. The sample mean, x , is an unbiased statistic because the mean value of the sampling distribution is equal to the population mean: mx m 2. Sample means vary from sample to sample. We don’t expect the sample mean to exactly equal the population mean m. 3. We do expect the sample mean to be close to the population mean. 4. Since closeness is measured in standard deviations, we expect the sample mean to be within 2 standard deviations of the population mean. Interval Estimate: An interval bounded by two values and used to estimate the value of a population parameter. The values that bound this interval are statistics calculated from the sample that is being used as the basis for the estimation. Level of Confidence 1 : The probability that the sample to be selected yields an interval that includes the parameter being estimated. Confidence Interval: An interval estimate with a specified level of confidence. Summary: • To construct a confidence interval for a population mean m, use the CLT. • Use the point estimate x as the central value of an interval. • Since the sample mean ought to be within 2 standard deviations of the population mean (95% of the time), we can find the bounds to an interval centered at x x 2( x ) to x 2( x ) • The level of confidence for the resulting interval is approximately 95%, or 0.95. • We can be more accurate in determining the level of confidence. Illustration: Distribution of x x 2( x ) m x x 2( x ) The interval x 2( x ) to x 2( x ) is an approximate 95% confidence interval for the population mean m. 8.2: Estimation of Mean m ( Known) • Formalize the interval estimation process as it applies to estimating the population mean m based on a random sample. • Assume the population standard deviation is known. • The assumptions are the conditions that need to exist in order to correctly apply a statistical procedure. The assumption for estimating the mean m using a known : The sampling distribution of x has a normal distribution. Assumption satisfied by: 1. Knowing that the sampling population is normally distributed, or 2. Using a large enough random sample (CLT). Note: The CLT may be applied to smaller samples (for example n = 15) when there is evidence to suggest a unimodal distribution that is approximately symmetric. If there is evidence of skewness, the sample size needs to be much larger. A (large sample) 1 confidence interval for m is found by x z 2 n to x z 2 n Note: 1. x is the point estimate and the center point of the confidence interval. 2. z(/2): confidence coefficient, the number of multiples of the standard error needed to construct an interval estimate of the correct width to have a level of confidence 1 . 1 /2 z( / 2) 0 /2 z( / 2) z 3. / n : standard error of the mean. The standard deviation of the distribution of x 4. z( / 2)( / n ) : maximum error of estimate E. One-half the width of the confidence interval (the product of the confidence coefficient and the standard error). 5. x z( / 2)( / n ) : lower confidence limit (LCL). x z( / 2)( / n ) : upper confidence limit (UCL). The Confidence Interval: A Five-Step Model: 1. Describe the population parameter of concern. 2. Specify the confidence interval criteria. a. Check the assumptions. b. Identify the probability distribution and the formula to be used. c. Determine the level of confidence, 1 . 3. Collect and present sample information. 4. Determine the confidence interval. a. Determine the confidence coefficient. b. Find the maximum error of estimate. c. Find the lower and upper confidence limits. 5. State the confidence interval. Example: The weights of full boxes of a certain kind of cereal are normally distributed with a standard deviation of 0.27 oz. A sample of 18 randomly selected boxes produced a mean weight of 9.87 oz. Find a 95% confidence interval for the true mean weight of a box of this cereal. Solution: 1. Describe the population parameter of concern. The mean, m, weight of all boxes of this cereal. 2. Specify the confidence interval criteria. a. Check the assumptions. The weights are normally distributed. The distribution of x is normal. b. Identify the probability distribution and formula to be used. Use the standard normal variable z with = 0.27. c. Determine the level of confidence, 1 . The question asks for 95% confidence: 1 = 0.95. 3. Collect and present information. The sample information is given in the statement of the problem. Given: n 18; x 9.87 4. Determine the confidence interval. a. Determine the confidence coefficient. The confidence coefficient is found using Table 4B: z( / 2) 1 1.15 0.75 1.28 0.80 1.65 0.90 1.96 0.95 2.33 0.98 2.58 0.99 b. Find the maximum error of estimate. Use the maximum error part of the formula for a CI. 0.27 E z 196 . 01247 . 2 n 18 c. Find the lower and upper confidence limits. Use the sample mean and the maximum error: x z to x z 2 n 2 n 9.87 01247 . to 9.87 01247 . 9.7453 to 9.9947 9.75 to 10.00 5. State the confidence interval. 9.75 to 10.00 is a 95% confidence interval for the true mean weight, m, of cereal boxes. Example: A random sample of the test scores of 100 applicants for clerk-typist positions at a large insurance company showed a mean score of 72.6. Determine a 99% confidence interval for the mean score of all applicants at the insurance company. Assume the standard deviation of test scores is 10.5. Solution: 1. Parameter of concern: the mean test score, m, of all applicants at the insurance company. 2. Confidence interval criteria. a. Assumptions: The distribution of the variable, test score, is not known. However, the sample size is large enough (n = 100) so that the CLT applies. b. Probability distribution: standard normal variable z with = 10.5. c. The level of confidence: 99%, or 1 = 0.99. 3. Sample information. Given: n = 100 and x = 72.6. 4. The confidence interval. a. Confidence coefficient: z( / 2) z(0.005) 2.58 b. Maximum error: E z( / 2)( / n ) (2.58)(10.5 / 100) 2.709 c. The lower and upper limits: 72.6 2.709 69.891 to 72.6 2.709 75309 . 5. Confidence interval: With 99% confidence we can say, “The mean test score is between 69.9 and 75.3.” 69.9 to 75.3 is a 99% confidence interval for the true mean test score. Note: The confidence is in the process. 95% confidence means: if we conduct the experiment over and over, and construct lots of confidence intervals, then 95% of the confidence intervals will contain the true mean value m. Sample Size: Problem: Find the sample size necessary in order to obtain a specified maximum error and level of confidence (assume the standard deviation is known). E z 2 n Solve this expression for n: z ( / 2) n E 2 Example: Find the sample size necessary to estimate a population mean to within .5 with 95% confidence if the standard deviation is 6.2. Solution: z ( / 2) n E 2 2 (196 . )(6.2) 2 24 . 304 590.684 .5 Therefore, n = 591. Note: When solving for sample size n, always round up to the next largest integer. (Why?) 8.3: The Nature of Hypothesis Testing • Formal process for making an inference. • Consider many of the concepts of a hypothesis test and look at several decisionmaking situations. • The entire process starts by identifying something of concern and then formulating two hypotheses about it. Hypothesis: A statement that something is true. Statistical Hypothesis Test: A process by which a decision is made between two opposing hypotheses. The two opposing hypotheses are formulated so that each hypothesis is the negation of the other. (That way one of them is always true, and the other on is always false.) Then one hypothesis is tested in hopes that it can be shown to be a very improbable occurrence thereby implying the other hypothesis is the likely truth. There are two hypotheses involved in making a decision. Null Hypothesis, H0: The hypothesis to be tested. Assumed to be true. Usually a statement that a population parameter has a specific value. The “starting point” for the investigation. Alternative Hypothesis, Ha: A statement about the same population parameter that is used in the null hypothesis. Generally this is a statement that specifies the population parameter has a value different, in some way, from the value given in the null hypothesis. The rejection of the null hypothesis will imply the likely truth of this alternative hypothesis. Note: 1. Basic idea: proof by contradiction. Assume the null hypothesis is true and look for evidence to suggest that it is false. 2. Null hypothesis: the status quo. A statement about a population parameter that is assumed to be true. 3. Alternative hypothesis: also called the research hypothesis. Generally, what you are trying to prove. We hope experimental evidence will suggest the alternative hypothesis is true by showing the unlikeliness of the truth of the null hypothesis. Example: Suppose you are investigating the effects of a new pain reliever. You hope the new drug relieves minor muscle aches and pains longer than the leading pain reliever. State the null and alternative hypotheses. Solution: H0: The new pain reliever is no better than the leading pain reliever. Ha: The new pain reliever lasts longer than the leading pain reliever. Example: You are investigating the presence of radon in homes being built in a new development. If the mean level of radon is greater than 4 then send a warning to all home owners in the development. State the null and alternative hypotheses. Solution: H0: The mean level of radon for homes in the development is 4 (or less). Ha: The mean level of radon for homes in the development is greater than 4. Hypothesis test outcomes: Decision Fail to reject H 0 Reject H 0 Null Hypothesis True False Type A correct decision Type II error Type I error Type B correct decision Type A correct decision: Null hypothesis true, decide in its favor. Type B correct decision: Null hypothesis false, decide in favor of alternative hypothesis. Type I error: Null hypothesis true, decide in favor of alternative hypothesis. Type II error: Null hypothesis false, decide in favor of null hypothesis. Example: A calculator company has just received a large shipment of parts used to make the screens on graphing calculators. They consider the shipment acceptable if the proportion of defective parts is 0.01 (or less). If the proportion of defective parts is greater than 0.01 the shipment is unacceptable and returned to the manufacturer. State the null and alternative hypotheses, and describe the four possible outcomes and the resulting actions that would occur for this test. Solution: H0: The proportion of defective parts is 0.01 (or less). Ha: The proportion of defective parts is greater than 0.01. Fail to Reject H0: Null Hypothesis Is True: Type A correct decision. Truth of situation: The proportion of defective parts is 0.01 (or less). Conclusion: It was determined that the proportion of defective parts is 0.01 (or less). Action: The calculator company received parts with an acceptable proportion of defectives. Null Hypothesis Is False: Type II error. Truth of situation: The proportion of defective parts is greater than 0.01. Conclusion: It was determined that the proportion of defective parts is 0.01 (or less). Action: The calculator company received parts with an unacceptable proportion of defectives. Reject H0: Null hypothesis is true: Type I error. Truth of situation: The proportion of defectives is 0.01 (or less). Conclusion: It was determined that the proportion of defectives is greater than 0.01. Action: Send the shipment back to the manufacturer. The proportion of defectives is unacceptable. Null hypothesis is false: Type B correct decision. Truth of situation: The proportion of defectives is greater than 0.01. Conclusion: It was determined that the proportion of defectives is greater than 0.01. Action: Send the shipment back to the manufacturer. The proportion of defectives is unacceptable. Note: 1. The type II error sometimes results in what represents a lost opportunity. 2. Since we make a decision based on a sample, there is always the chance of making an error. Probability of a type I error = . Probability of a type II error = b. Error in Decision Rejection of a true H 0 Failure to reject a false H 0 Type I II Probability b Correct Decision Failure to reject a true H 0 Rejection of a false H 0 Type A B Probability 1- 1-b Note: 1. Would like and b to be as small as possible. 2. and b are inversely related. 3. Usually set (and don’t worry too much about b. Why?) 4. Most common values for and b are 0.01 and 0.05. 5. 1 b: the power of the statistical test. A measure of the ability of a hypothesis test to reject a false null hypothesis. 6. Regardless of the outcome of a hypothesis test, we never really know for sure if we have made the correct decision. Interrelationship between the probability of a type I error (), the probability of a type II error (b), and the sample size (n). P(type I error) P (type II error) b Sample Size n Level of Significance : The probability of committing the type I error. Test Statistic: A random variable whose value is calculated from the sample data and is used in making the decision fail to reject H0 or reject H0. Note: 1. The value of the test statistic is used in conjunction with a decision rule to determine fail to reject H0 or reject H0. 2. The decision rule is established prior to collecting the data and specifies how you will reach the decision. The Conclusion: a. If the decision is reject H0, then the conclusion should be worded something like, “There is sufficient evidence at the level of significance to show that . . . (the meaning of the alternative hypothesis).” b. If the decision is fail to reject H0, then the conclusion should be worded something like, “There is not sufficient evidence at the level of significance to show that . . . (the meaning of the alternative hypothesis).” Note: 1. The decision is about H0. 2. The conclusion is a statement about Ha. 3. There is always the chance of making an error. 8.4: Hypothesis Test of Mean m ( known): A ProbabilityValue Approach • The concepts and much of the reasoning behind hypothesis tests are given in the previous sections. • Formalize the hypothesis test procedure as it applies to statements concerning the mean m of a population ( known): a probabilityvalue approach. The assumption for hypothesis tests about a mean m using a known : The sampling distribution of x has a normal distribution. Recall: 1. The distribution of x has mean m. 2. The distribution of x has standard deviation n Hypothesis test: 1. A well-organized, step-by-step procedure used to make a decision. 2. Probability-value approach (p-value approach): a procedure that has gained popularity in recent years. Organized into five steps. The Probability-Value Hypothesis Test: A Five-Step Procedure: 1. The Set-Up: a. Describe the population parameter of concern. b. State the null hypothesis (H0) and the alternative hypothesis (Ha). 2. The Hypothesis Test Criteria: a. Check the assumptions. b. Identify the probability distribution and the test statistic formula to be used. c. Determine the level of significance, . 3. The Sample Evidence: a. Collect the sample information. b. Calculate the value of the test statistic. 4. The Probability Distribution: a. Calculate the p-value for the test statistic. b. Determine whether or not the p-value is smaller than . 5. The Results: a. State the decision about H0. b. State a conclusion about Ha. Example: A company advertises the net weight of its cereal is 24 ounces. A consumer group would like to check this claim. They cannot check every box of cereal, so a sample of cereal boxes will be examined. A decision will be made about the true mean weight based on the sample mean. State the consumer group’s null and alternative hypotheses. Assume = .2. Solution: 1. The Set-Up: a. Describe the population parameter of concern. The population parameter of interest is the mean m, the mean weight of the cereal boxes. b. State the null hypothesis (H0) and the alternative hypothesis (Ha). Formulate two opposing statements concerning m. H0: m = 24 ( ) (the mean is at least 24) Ha: m < 24 (the mean is less than 24) Note: The trichotomy law from algebra states that two numerical values must be related in exactly one of three possible relationships: <, =, or >. All three of these possibilities must be accounted for between the two opposing hypotheses in order for the hypotheses to be negations of each other. Possible Statements of Null and Alternative Hypotheses: Null Hypothesis 1. greater than or equal to () 2. less than or equal to () 3. equal to () Alternative Hypothesis less than () greater than () not equal to () Note: 1. The null hypothesis will be written with just the equal sign (a value is assigned). 2. When equal is paired with less than or greater than, the combined symbol is written beside the null hypothesis as a reminder that all three signs have been accounted for in these two opposing statements. Example: An automobile manufacturer claims a new model gets at least 27 miles per gallon. A consumer groups disputes this claim and would like to show the mean miles per gallon is lower. State the null and alternative hypotheses. Solution: H0: m = 27 () and Ha: m < 27 Example: A freezer is set to cool food to 10 . If the temperature is higher, the food could spoil, and if the temperature is lower, the freezer is wasting energy. Random freezers are selected and tested as they come off the assembly line. The assembly line is stopped if there is any evidence to suggest improper cooling. State the null and alternative hypotheses. Solution: H0: m = 10 and Ha: m 10 Common Phrases and Their Negations: H 0 : ( ) H a : () at least no less than not less than less than less than less than H 0 : ( ) at most no more than not greater than H a : ( ) more than more than greater than H 0 : ( ) is not different from same as H a : () is not different from not same as Example (continued): Weight of cereal boxes. Recall: H0: m = 24 () (at least 24) Ha: m < 24 (less than 24) 2. The Hypothesis Test Criteria: a. Check the assumptions. The weight of cereal boxes is probably mound shaped. A sample size of 40 should be sufficient for the CLT to apply. The sampling distribution of the sample mean can be expected to be normal. b. Identify the probability distribution and the test statistic to be used. To test the null hypothesis, ask how many standard deviations away from m is the sample mean. xm test statistic : z* n c. Determine the level of significance. Consider the four possible outcomes and their consequences. Let = 0.05. 3. The Sample Evidence: a. Collect the sample information. A random sample of 40 cereal boxes is examined. x 23.95 and n 40 b. Calculate the value of the test statistic. ( = .2) z* x m 23.95 24 1.5811 n .2 40 4. The Probability Distribution: a. Calculate the p-value for the test statistic. Probability-Value, or p-Value: The probability that the test statistic could be the value it is or a more extreme value (in the direction of the alternative hypothesis) when the null hypothesis is true (Note: the symbol P will be used to represent the p-value, especially in algebraic situations.) P 1.58 0 z P P( z z*) P( z 1.58) P( z 1.58) .05000 0.4429 0.0571 b. Determine whether or not the p-value is smaller than . The p-value (0.0571) is greater than (0.05). 5. The Results: Decision Rule: a. If the p-value is less than or equal to the level of significance , then the decision must be to reject H0. b. If the p-value is greater than the level of significance , then the decision must be to fail to reject H0. a. State the decision about H0. Decision about H0 : Fail to reject H0. b. Write a conclusion about Ha. There is not sufficient evidence at the 0.05 level of significance to show that the mean weight of cereal boxes is less than 24 ounces. Note: 1. If we fail to reject H0, there is no evidence to suggest the null hypothesis is false. This does not mean H0 is true. 2. The p-value is the area, under the curve of the probability distribution for the test statistic, that is more extreme than the calculated value of the test statistic. 3. There are 3 separate cases for p-values. The direction (or sign) of the alternative hypothesis is the key. Finding p-values: 1. Ha contains > (Right tail) p-value = P(z > z*) 0 z* z 0 | z* | z | z* | 0 | z* | z 2. Ha contains < (Left tail) p-value = P(z < z*) z* 3. Ha contains (Two-tailed) p-value = P(z < |z*|) + P(z > |z*|) Example: The mean age of all shoppers at a local jewelry store is 37 years (with a standard deviation of 7 years). In an attempt to attract older adults with more disposable income, the store launched a new advertising campaign. Following the advertising, a random sample of 47 shoppers showed a mean age of 39.3. Is there sufficient evidence to suggest the advertising campaign has succeeded in attracting older customers? Solution: 1. The Set-Up: a. Parameter of concern: the mean age, m, of all shoppers. b. The hypotheses: H0: m = 37 () Ha: m > 37 2. The Hypothesis Test Criteria: a. The assumptions: The distribution of the age of shoppers is unknown. However, the sample size is large enough for the CLT to apply. b. The test statistic: The test statistic will be z*. c. The level of significance: none given. We will find a pvalue. 3. The Sample Evidence: a. Sample information: n 47, x 39.3 b. Calculated test statistic: x m 39.3 37 z* 2.25 n 7 47 4. The Probability Distribution: a. The p-value: p - value P ( z z*) P ( z 2.25) 0.5000 0.4878 0.0122 2.25 0 b. Determine whether or not the p-value is smaller than . A comparison is not possible, no given. 5. The Results: Because the p-value is so small (P < 0.05), there is evidence to suggest the mean age of shoppers at the jewelry store is greater than 37. z The idea of the p-value is to express the degree of belief in the null hypothesis: 1. When the p-value is minuscule (like 0.0001), the null hypothesis would be rejected by everyone because the sample results are very unlikely for a true H0. 2. When the p-value is fairly small (like 0.01), the evidence against H0 is quite strong and H0 will be rejected by many. 3. When the p-value begins to get larger (say, 0.02 to 0.08), there is too much probability that data like the sample involved could have occurred even if H0 were true, and the rejection of H0 is not an easy decision. 4. When the p-value gets large (like 0.15 or more), the data is not at all unlikely if the H0 is true, and no one will reject H0. Advantages of p-value approach: 1. The results of the test procedure are expressed in terms of a continuous probability scale from 0.0 to 1.0, rather than simply on a reject or fail to reject basis. 2. A p-value can be reported and the user of the information can decide on the strength of the evidence as it applies to his/her own situation. 3. Computers can do all the calculations and report the pvalue, thus eliminating the need for tables. Disadvantage: Tendency for people to put off determining the level of significance. Example: The active ingredient for a drug is manufactured using fermentation. The standard process yields a mean of 26.5 grams (assume = 3.2). A new mixing technique during fermentation is implemented. A random sample of 32 batches showed a sample mean 27.1. Is there any evidence to suggest the new mixing technique has changed the yield? Solution: 1. The Set-Up: a. The parameter of interest is the mean yield of active ingredient, m. b. The null and alternative hypotheses: H0: m = 26.5 Ha: m 26.5 2 The Hypothesis Test Criteria: . a. Assumptions: A sample of size 32 is large enough to satisfy the CLT. b. The test statistic: z* c. The level of significance: find a p-value. 3. The Sample Evidence: a. From the sample: n 32, x 27.1 b. The calculated test statistic: z* x m 27.1 26.5 1.06 n 3.2 32 4. The Probability Distribution: a. The p-value: p - value 2 P ( z | z* |) 2 P ( z 1.06) 2 (0.5000 0.3554) 2 0.1446 0.2892 0 1.06 b. The p-value is large. There is no given in the statement of the problem. Note: Suppose we took repeated samples of size 32. 1. What results would you expect? 2. What does the p-value really measure? z 5. The Results: Because the p-value is large (P = 0.2892), there is no evidence to suggest the new mixing technique has changed the mean yield. 8.5: Hypothesis Test of mean m ( known): A Classical Approach • Concepts and reasoning behind hypothesis testing given in previous section. • Formalize the hypothesis test procedure as it applies to statements concerning m of a population with known : a classical approach. The assumption for hypothesis tests about mean m using a known : The sampling distribution of x has a normal distribution. Recall: 1. The distribution of x has mean m. 2. The distribution of x has standard deviation n Hypothesis test: 1. A well-organized, step-by-step procedure used to make a decision. 2. The classical approach is the hypothesis test process that has enjoyed popularity for many years. The Classical Hypothesis Test: A Five-Step Procedure: 1. The Set-Up: a. Describe the population parameter of concern. b. State the null hypothesis (H0) and the alternative hypothesis (Ha). 2. The Hypothesis Test Criteria: a. Check the assumptions. b. Identify the probability distribution and the test statistic to be used. c. Determine the level of significance, . 3. The Sample Evidence: a. Collect the sample information. b. Calculate the value of the test statistic. 4. The Probability Distribution: a. Determine the critical region(s) and critical value(s). b. Determine whether or not the calculated test statistic is in the critical region. 5. The Results: a. State the decision about H0. b. State the conclusion about Ha. Example: A company advertises the net weight of its cereal is 24 ounces. A consumer group would like to check this claim. They cannot check every box of cereal, so a sample of cereal boxes will be examined. A decision will be made about the true mean weight based on the sample mean. State the consumer group’s null and alternative hypotheses. Assume = .2. Solution: 1. The Set-Up: a. Describe the population parameter of concern. The population parameter of interest is the mean, m, the mean weight of the cereal boxes. b. State the null hypothesis (H0) and the alternative hypothesis (Ha). Formulate two opposing statements concerning the m. H0: m = 24 ( ) (the mean is at least 24) Ha: m < 24 (the mean is less than 24) Note: The trichotomy law from algebra states that two numerical values must be related in exactly one of three possible relationships: <, =, or >. All three of these possibilities must be accounted for between the two opposing hypotheses in order for the hypotheses to be negations of each other. Possible Statements of Null and Alternative Hypotheses: Null Hypothesis 1. greater than or equal to () 2. less than or equal to () 3. equal to () Alternative Hypothesis less than () greater than () not equal to () Note: 1. The null hypothesis will be written with just the equal sign (a value is assigned). 2. When equal is paired with less than or greater than, the combined symbol is written beside the null hypothesis as a reminder that all three signs have been accounted for in these two opposing statements. Example: An automobile manufacturer claims a new model gets at least 27 miles per gallon. A consumer groups disputes this claim and would like to show the mean miles per gallon is lower. State the null and alternative hypotheses. Solution: H0: m = 27 () and Ha: m < 27 10 Example: A freezer is set to cool food to . If the temperature is higher, the food could spoil, and if the temperature is lower, the freezer is wasting energy. Random freezers are selected and tested as they come off the assembly line. The assembly line is stopped if there is any evidence to suggest improper cooling. State the null and alternative hypotheses. Solution: H0: m = 10 and Ha: m 10 Common Phrases and Their Negations: H 0 : ( ) H a : () at least no less than not less than less than less than less than H 0 : ( ) H a : ( ) at most no more than not greater than more than more than greater than H 0 : ( ) is not different from same as H a : () is not different from not same as Example (continued): Weight of cereal boxes. Recall: H0: m = 24 () (at least 24) Ha: m < 24 (less than 24) 2. The Hypothesis Test Criteria: a. Check the assumptions. The weight of cereal boxes is probably mound shaped. A sample size of 40 should be sufficient for the CLT to apply. The sampling distribution of the sample mean can be expected to be normal. b. Identify the probability distribution and the test statistic to be used. To test the null hypothesis, ask how many standard deviations away from m is the sample mean. xm test statistic : z* n c. Determine the level of significance. Consider the four possible outcomes and their consequences. Let = 0.05. 3. The Sample Evidence: a. Collect the sample information. A random sample of 40 cereal boxes is examined. x 23.95 and n 40 b. Calculate the value of the test statistic. ( = .2) x m 23.95 24 z* 1.5811 n .2 40 4. The Probability Distribution: a. Determine the critical region(s) and critical value(s). Critical Region: The set of values for the test statistic that will cause us to reject the null hypothesis. The set of values that are not in the critical region is called the noncritical region (sometimes called the acceptance region). Critical Value(s): The first or boundary value(s) of the critical region(s). Illustration: Critical Region and Critical Value(s). 0.05 1.65 Critical Region 0 Critical Value z b. Determine whether or not the calculated test statistic is in the critical region. Location of z* z* 1.58 0 z 1.65 The calculated value of z, z* = 1.58, is in the noncritical region. 5. The Results: We need a decision rule. Decision Rule: a. If the test statistic falls within the critical region, we will reject H0. (The critical value is part of the critical region.) b. If the test statistic is in the noncritical region, we will fail to reject H0. a. State the decision about H0. Decision: Fail to reject H0. b. State the conclusion about Ha. Conclusion: There is not enough evidence at the 0.05 level of significance to show that the mean weight of cereal boxes is less than 24. Note: 1. The null hypothesis specifies a particular value of a population parameter. 2. The alternative hypothesis can take three forms. Each form dictates a specific location of the critical region(s). 3. For many hypothesis tests, the sign in the alternative hypothesis points in the direction in which the critical region is located. Sign in the Alternative Hypothesis Critical Region One region Left side One-tailed test 4. Significance level: Two regions One region Half on each side Right side Two-tailed test One-tailed test Example: The mean water pressure in the main water pipe from a town well should be kept at 56 psi. Anything less and several homes will have an insufficient supply, and anything greater could burst the pipe. Suppose the water pressure is checked at 47 random times. The sample mean is 57.1. (Assume = 7.) Is there any evidence to suggest the mean water pressure is different from 56? Use = 0.01. Solution: 1. The Set-Up: a. Describe the parameter of concern: The mean water pressure in the main pipe. b. State the null and alternative hypotheses. H0: m = 56 Ha: m 56 2. The Hypothesis Test Criteria: a. Check the assumptions: A sample of n = 47 is large enough for the CLT to apply. b. Identify the test statistic. The test statistic is z*. c. Determine the level of significance: = 0.01 (given) 3. The Sample Evidence: a. The sample information: x 57.1, n 47 b. Calculate the value of the test statistic: x m 57.1 56 z* 1.077 n 7 47 4. The Probability Distribution: a. Determine the critical regions and the critical values. 0.005 0.005 2.58 0 2.58 z b. Determine whether or not the calculated test statistic is in the critical region. The calculated value of z, z* = 1.077, is in the noncritical region. 5. The Results: a. State the decision about H0. Fail to reject H0. c. State the conclusion about Ha. There is no evidence to suggest the water pressure is different from 56. Example: An elementary school principal claims students receive no more than 30 minutes of homework each night. A random sample of 36 students showed a sample mean of 36.8 minutes spent doing homework (assume = 7.5). Is there any evidence to suggest the mean time spent on homework is greater than 30 minutes? Use = 0.05. Solution: 1. The parameter of concern: m, the mean time spent doing homework each night. H0: m = 30 () Ha: m > 30 2. The Hypothesis Test Criteria: a. The sample size is n = 36, the CLT applies. b. The test statistic is z*. c. The level of significance is given: = 0.01. 3. The Sample Evidence: x 36.8, z* n 36 x m 36.8 30 5.44 n 7.5 36 4. The Probability Distribution: 0.01 0 2.33 z The calculated value of z, z* = 5.44, is in the critical region. 5. The Results: Decision: Reject H0. Conclusion: There is sufficient evidence at the 0.01 level of significance to conclude the mean time spent on homework by the elementary students is more than 30 minutes. Note: Suppose we took repeated sample of size 36. What would you expect to happen?