SPRING 2004 VOL.45 NO.3

MITSloan

Management Review

Jeffrey H. Dyer and Nile W. Hatch

Using Supplier Networks

to Learn Faster

Please note that gray areas reflect artwork that has

been intentionally removed. The substantive content

of the article appears as originally published.

REPRINT NUMBER 45311

Using Supplier Networks

to Learn Faster

Many companies keep

L

ast year, Toyota Motor Corp. posted profits that exceeded the combined earnings of

its three largest competitors. In today’s world of hypercompetition, how did Toyota

accomplish this? In searching for the answer, many business gurus and researchers have

overlooked — or have not fully understood — the importance of knowledge-sharing

networks. Certainly, knowledge management has become a hot topic. But how exactly do

firms learn, and why do some companies learn faster than others? Furthermore, does

learning go beyond the boundaries of the organization?

Many companies keep their suppliers and partners at arm’s length, zealously guarding

their internal knowledge. In sharp contrast, Toyota embraces its suppliers and encourages

knowledge sharing with them by establishing networks that facilitate the exchange of

information. By doing so, Toyota has helped those companies retool and fine-tune their

operations, and the results have been stunning: 14% higher output per worker, 25% lower

inventories and 50% fewer defects compared with their operations that supply Toyota’s

rivals. Such improvements have provided Toyota with a significant competitive advantage,

enabling the company to charge substantial price premiums for the enhanced quality of

its products. As Koichiro Noguchi, a Toyota director and

former purchasing head, puts it, “Our suppliers are critical to

our success. We must help them to be the best.”

Toyota is not alone. More and more, companies are recognizing the competitive advantage that springs from the manner in

which they work with their partners. Even powerful Microsoft

Corp. has to rely on companies around the world to localize and

translate its products in markets as diverse as those of China,

Chile and the Czech Republic. Ultimately Microsoft’s speed to

market and even the quality of its offerings in those countries

depend directly on how well it works and shares knowledge with

those firms. For computer-systems company Dell Inc., suppliers

are the very lifeblood of its business, and effective knowledge

sharing with those partners is crucial for the company’s success

(see “Knowledge Sharing at Dell,” p. 59). Other firms like

Boeing, Harley-Davidson and Xilinx, a semi-

their suppliers at arm’s

length. But partnering

with vendors — sharing

valuable knowledge with

them through organized

networks — can be a

sustainable source of

competitive advantage.

Jeffrey H. Dyer and

Nile W. Hatch

Jeffrey H. Dyer is the Horace Beesley Professor of Global Strategy

and Nile W. Hatch is assistant professor of strategy at the Marriott

School, Brigham Young University, in Provo, Utah. They can be

reached at jdyer@byu.edu and nile@byu.edu.

SPRING 2004 MIT SLOAN MANAGEMENT REVIEW

57

conductor manufacturer headquartered in San Jose, California,

have also realized the importance of knowledge sharing with

partners, and they are looking at strengthening those processes.

As Xilinx vice president Evert Wolsheimer states, “I think our

partnership relationships will evolve in a similar direction over

time to look like what Toyota has done.”

Learning at Toyota

So what exactly has Toyota done? To answer this, we performed an

in-depth study of Toyota and its suppliers (see “About the

Research”) and found that the company has developed an infrastructure and a variety of interorganizational processes that facilitate

the transfer of both explicit and tacit knowledge within its supplier

network. (See “Two Types of Knowledge,” p. 60.) The effort,

headed by the company’s purchasing division and its operations

management consulting division (OMCD), consists of three key

processes: supplier associations, consulting groups and learn-ing

teams. (See “How Toyota Facilitates Network Learning,” p. 61.)

Supplier Associations In 1989, Toyota started an association for

its U.S. suppliers. Named the Bluegrass Automotive Manufacturers Association (BAMA), the group was modeled after Toy-

About the Research

Toyota has long excelled at transferring productivityenhancing knowledge throughout its network of suppliers.i

From 1965 to 1992, for example, the company and its suppliers increased their labor productivity by roughly 700%. In

contrast, during the same time period U.S. automakers and

their vendors achieved productivity increases of 250% and

less than 50%, respectively.

To examine the mechanisms that Toyota and its suppliers have successfully employed to share knowledge with

each other, we conducted an extensive study, consisting of

more than 100 hours of interviews with more than 30 Toyota executives. We also surveyed more than 80 of Toyota’s

suppliers in both Japan and the United States, and we conducted interviews with dozens of their senior executives.

The investigation looked not only at how Toyota transferred knowledge to its suppliers but also at how the company was able to tap into the potential of knowledge

located outside the organization. Further, we examined the

ways in which that system of knowledge sharing had created superior competitive advantage and profits for both

Toyota and its suppliers.

i. T. Nishiguchi, “Strategic Industrial Sourcing” (New York: Oxford University

Press, 1994); and M. Lieberman, “The Diffusion of ‘Lean Manufacturing’ in

the Japanese and U.S. Automotive Industry,” presented at the New

Imperatives for Managing Revolutionary Change Conference in Shizuoka,

Japan, Aug. 29, 1994.

ota’s supplier association in Japan (called kyohokai). The initial

objective was to provide a regular forum for Toyota to share

information with and elicit feedback from suppliers. Membership

was voluntary, but word gradually spread about the value of

joining the association. By 2000, BAMA had grown to 97

suppliers from an original membership of just 13. According to

Toyota’s Chris Nielsen, general manager for purchasing planning, “We really didn’t know if this would work in the U.S. ...

Before BAMA, it was not very natural for supplier executives to

talk and share information.... Over the years, that has changed as

suppliers have built relationships at senior levels.”

Details of the kyohokai reveal the various mechanisms

through which knowledge is shared. The supplier association

holds both general-assembly meetings (bimonthly) and topic

committee meetings (monthly or bimonthly). The former enable

high-level sharing of explicit knowledge regarding pro-duction

plans, policies, market trends and so on within the sup-ply

network. The latter allow more frequent interactions on four

specific subject areas — cost, quality, safety and social activities

— which are generally of benefit to all members of the network.

The quality committee, for example, picks a theme for the year,

such as “eliminating supplier design defects,” and meets

bimonthly to share knowledge with regard to that particular

topic. The quality committee also sponsors various activities,

including basic quality training for more than 100 engineers

each year, tours of “best practice” plants both inside and outside

the automotive industry, and an annual conference on quality

management that highlights in-depth supplier cases of quality

improvement selected by a panel. Such efforts, in conjunction

with those of the other committees, not only provide a forum for

sharing valuable knowledge, they also help develop

relationships among the participating suppliers.

Consulting/Problem-Solving Groups As early as the mid-1960s,

Toyota began to provide expert consultants to assist its suppliers

in Japan. To that end, the company established the OMCD for

acquiring, storing and diffusing valuable production knowledge

residing within the Toyota Group. The OMCD consists of six

highly experienced senior executives (each of them has

responsibility for two Toyota plants and approximately 10 suppliers) along with about 50 consultants. About 15 to 20 of those

consultants are permanent members of the OMCD, while the rest

are fast-track younger individuals who deepen their knowledge

of the Toyota Production System (TPS) by spending a three- to

five-year rotation at the OMCD. Toyota sends these inhouse

experts to suppliers, sometimes for months at a time, to help

those companies solve problems in implementing the TPS.

Interestingly, Toyota does not charge for its consultants’ time,

instead making the OMCD a resource available to all members

of the Toyota Group. Our survey of 38 of Toyota’s largest first58 MIT SLOAN MANAGEMENT REVIEW SPRING 2004

Knowledge Sharing at Dell

Knowledge sharing with partners is the

plier plants to monitor performance, share

PC makers to establish a Web portal for

foundation of Dell Inc.’s efforts toward

process knowledge for improving quality

supplier collaboration, providing vendor

“virtual integration.” According to CEO

and yields, and encourage the better

partners with access to Dell systems and

Michael Dell, “‘Virtual integration’ means

vendors to share their know-how with

key information regarding product design

you basically stitch together a business

others. Fifth, Dell has worked on its own

and engineering, cost manage-ment and

with partners that are treated as if

internal operations to facilitate greater and

quality. This system is part of a greater

they’re inside the company.” i To achieve

faster knowledge transfer. For example,

effort to share important infor-mation

that, Dell has implemented a variety of

the company returns defective parts much

with suppliers, including detailed data

measures.

more quickly than its competitors do,

regarding product demand, backlogs,

providing suppliers with valuable data

pipelines and inventories.

First, Dell has taken minority equity

stakes in a few key vendors. Second, it

earlier on. “Returned parts on Dell’s

The importance of such knowledge-

encourages its top suppliers to locate

products usually reach us in 30 days

sharing practices at Dell should not be

their resources inside or near Dell’s

versus 90 days for competitors,” says

underestimated. “Our business model is

design centers and factories. Third, it has

Maxtor’s Perry. “As a result, we can work

based on direct relationships, not only

implemented a certification program that

together to fix problems quickly, which

with our customers but also [with] our

is unique among major PC manufacturers.

keeps warranty costs low.” Sixth, suppli-

partners,” notes Dell President and COO

According to Scott Perry, senior director

ers’ engineers visit Dell plants to help both

Kevin B. Rollins. “Close supplier relation-

of global sales at Maxtor Corp., a

Dell and the suppliers improve product

ships influence everything from planning

manufacturer of computer hard drives,

quality and process capabilities. These

and forecasting to improved quality,

“Dell’s certification process teaches our

engineers conduct failure analyses at

pricing, inventory management, produc-

engineers the language, processes and

Dell’s factories, after which they trans-fer

tion and fulfillment. We’re constantly

metrics used by Dell. In short, it teaches

the resulting knowledge to their own

looking for ways to integrate our suppli-

them how to think like Dell. This is critical

facilities for corrective and preventive

ers and partners more closely into our

because Dell wants our engineers to

actions. Seventh, Dell coordinates its

business through substituting informa-

monitor processes both in our factories

knowledge-sharing activities by meeting

tion for inventory and cost.”

and at Dell factories using the tools,

weekly with key suppliers and by holding

processes and metrics preferred by Dell.”

quarterly business reviews with their top

Fourth, Dell engineers routinely visit sup-

executives. Lastly, Dell is one of the first

tier suppliers in Japan revealed that, on average, they received

4.2 visits per year, each lasting 3.1 days.

In 1992, Toyota established the U.S. version of the OMCD.

Originally called the Toyota Supplier Support Center (now TSSC

Inc.), the group has since grown to more than 20 consultants and

is headed by general manager Hajime Ohba, who is a former

OMCD consultant. Like the OMCD, the TSSC requires that participating suppliers share their project results with others. This

policy allows Toyota to showcase “best practice” suppliers that

have successfully implemented various elements of the TPS, and

it encourages the suppliers to open their operations to one another.

This is critical because the ability to see a working template

dramatically increases the chances that suppliers can successfully

replicate that knowledge within their own plants. Companies can,

however, designate certain areas of their plants — where Toyota

hasn’t provided any assistance — as off-limits to visitors in order

to protect their proprietary knowledge.

To date, transfers of TPS know-how have been difficult and

time-consuming. Although the goal is to achieve success in six

i. J. Magretta, “The Power of Virtual Integration: An

Interview With Dell Computer’s Michael Dell,” Harvard Business Review 76 (March-April 1998): 72-84.

months, no project in the United States has been completed in less

than eight months and most consume at least a year and a half. “It

takes a very long time and tremendous commitment to implement

the Toyota Production System,” says Ohba. “In many cases it

takes a total cultural and organizational change. Many U.S. firms

have management systems that contradict where you need to go.”

Consider Summit Polymers Inc., a manufacturer of plastic interior

parts, based in Kalamazoo, Michigan, which was one of the first

U.S. suppliers to use the TSSC. According to Tom Luyster, who

was vice president of planning at the time, “The TSSC sent

approximately two to four consultants to our plant every day for a

period of three to four months as we attempted to implement TPS

concepts in a new plant.” And after that initial phase, Toyota

continued to provide ongoing support to Summit Polymers for

more than five years.

But the results have been impressive. On average, the TSSC

has assisted suppliers in increasing productivity (in output per

worker) by 123% and reducing inventory by 74%. These

improvements clearly demonstrate that, although the TSSC’s

SPRING 2004 MIT SLOAN MANAGEMENT REVIEW 59

knowledge-transfer processes require considerable effort, they

can dramatically improve supplier performance.

Take, for example, Continental Metal Specialty (CMS), a supplier of metal stampings, such as body brackets. The consulting

process began with Toyota sending people to teach the TPS to

CMS personnel, after which the two companies jointly examined

CMS’s production process to identify each step, flagging those

that were value-added versus those that were not. Out of 30 steps,

four were designated as value-added: blanking, forming, welding

and painting. Toyota and CMS then reconfigured the production

system to eliminate as many of the non-value-added steps as possible. One important change brought welding into the plant and

placed it next to the forming process, thereby eliminating 12 nonvalue-added steps. Over time, CMS has eliminated a total of 19

non-value-added steps, reducing setup times from two hours to 12

minutes. In addition, inventories on most parts have been reduced

to almost one-tenth of previous levels. Then CMS chairman

George Hommel described the benefits: “We wouldn’t be

Two Types of Knowledge

where we are now if we hadn’t worked with Toyota. I’d say

that 75% to 80% of all that we’ve learned from customers has

come from Toyota.”

It should be noted that Toyota does not ask for immediate

price decreases or a portion of the savings from the improvements. Suppliers keep all of the initial benefits, in contrast with

the General Motors Corp. (GM) typical practice of asking for a

price decrease after offering assistance at a supplier’s plant. As

one supplier executive declared, “We don’t want to have a GM

team poking around our plant. They will just find the ‘low-hanging fruit’ — the stuff that’s relatively easy to see and fix. ... We’d

prefer to find it ourselves and keep all of the savings.” Of course,

Toyota does eventually capture some of the savings through its

annual price reviews with suppliers, but the company is careful to

keep activities that create value completely separate from those

that appropriate value. For example, Toyota has typically used a

“target-pricing” system by which the company lets suppliers

know the prices it thinks are fair for certain parts for the duration

of a contract.l This motivates suppliers to cut costs continually to

reap higher profits on those parts.

Voluntary Learning Teams In 1977, the OMCD organized more

than 50 of its key suppliers in Japan into voluntary study groups

(called jishukenkyu-kai, or jishuken) to work together on productivity and quality improvements. With the help of an OMCD

consultant, the teams determined a theme and spent three

months addressing the problems of each of its members’ plants.

Jishuken are an advanced knowledge-sharing mechanism

through which members learn as a group, exploring new ideas

and applications of TPS. The team then transfers any valuable

lessons to Toyota and throughout the supplier network.

In 1994, Toyota replicated the jishuken concept in the United

States by establishing three plant development activity (PDA) core

groups among 40 suppliers. As with the supplier association,

membership was voluntary. For the first year, the theme was

quality improvement because, as Toyota’s Chris Nielsen noted,

“everyone agrees that they can improve quality.” Each PDA member was asked to select a demonstration line within a plant as a

place to experiment with implementing certain concepts.

Our interviews with U.S. plant managers revealed the value

of the PDA projects. According to one manager, “When you

bring a whole new set of eyes into your plant, you learn a lot. ...

We’ve made quite a few improvements. In fact, after the [PDA]

group visits to our plant, we made more than 70 changes to the

manufacturing cell.”

A key reason that PDA transfers of tacit knowledge have been

particularly effective is that they involve learning that is contextspecific. The plant manager from Kojima Press Industry Co. Ltd.,

a supplier of body parts, describes an example: “Last year we

reduced our paint costs by 30%. This was possible due to a sug-

Most scholars divide knowledge into two types: explicit and

tacit.' The former can be codified easily and transmitted

without loss of integrity once the rules required for

deciphering it are known. Examples include facts,

axiomatic propositions and symbols that provide information on the size and growth of a market, production schedules and so on. In contrast, tacit knowledge is “sticky,”

complex and difficult to codify, ii and it often involves experiential learning. One example is the know-how required to

transform a manufacturing plant from mass production to

flexible operation. Because tacit knowledge is complex and

difficult to imitate, it is most likely to generate competitive

advantages that are sustainable. In fact, in The Knowledge

Creating Company, researchers Ikujiro Nonaka and

Hiroyuki Takeuchi make the case that the really powerful

type of knowledge is tacit because it is the primary source

of innovative new products and creative ways of doing

business. '''

i. B. Kogut and U. Zander, “Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of Technology,” Organization Science 3, no. 3

(1992): 383-397; R. Grant, “Prospering in Dynamically-Competitive Environments: Organizational Capability as Knowledge Integration,” Organization Science 7, no. 4 (1996): 375-387; and G. Ryle, “The Concept of

Mind” (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984): 29-34.

ii. R. Nelson and S. Winter, “An Evolutionary Theory of Economic

Change” (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1982); B. Kogut and U. Zander,

“Knowledge of the Firm” (1992); and G. Szulanski, “Exploring Internal

Stickiness: Impediments to the Transfer of Best Practice Within the

Firm,” Strategic Management Journal 17 (1996): 27-43.

iii. I. Nonaka and H. Takeuchi, “The Knowledge Creating Company”

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1995).

60

MIT SLOAN MANAGEMENT REVIEW SPRING 2004

gestion to lower the pressure on the paint sprayer and adjust the

spray trajectory, thereby wasting less paint.”

The Evolution of a Knowledge-Sharing Network

other. Companies were motivated to participate in the supplier

association primarily to demonstrate their commitment to Toyota with the hope that they would then be rewarded with additional future business. At this point, the network was just

beginning to develop an identity, and suppliers did not yet perceive a strong sense of shared purpose with other members.

Next, Toyota gradually increased the strength of its bilateral

relationships with suppliers by sending consultants to transfer

The successful structures and collaborative relationships of the

three knowledge-sharing processes — the supplier association,

consulting groups and learning teams — did not appear by happenstance. Rather, Toyota established these institutions in the

same order in both the United States

and Japan. The intent was first to create

weak, nonthreatening ties that could

As each structure evolved and the relationships matured, the processes

later be transformed into strong, trusting relationships. As each structure

became a vehicle for a shared identity among Toyota suppliers.

evolved and the relationships matured,

the processes became a vehicle for a

shared identity among Toyota suppliers. As one supplier executive put it, “We’re a member of the

valuable knowledge at minimal cost. Consequently, suppliers

Toyota Group. That means we are willing to do what we can to

increasingly participated in the network not only to demonstrate

help other group members.”

their commitment to Toyota but also to learn from the company.

In the initiation phase of Toyota’s U.S. network (roughly from

Although the supplier association facilitated the exchange of

1989 to 1992), the network structure was a collection of dyadic ties

information that was primarily explicit, the personal visits of

consultants were effective in transferring tacit knowledge of

with Toyota as a hub that heavily subsidized activities. (See

“Evolution of Toyota Network,” p. 62.) Toyota’s help came in two

greater value. And the consultants created an atmosphere of reciprocity: Suppliers began to feel indebted to Toyota for sharing

forms: financial (for instance, funds for planning and organizing

knowledge that significantly improved their operations.

meetings) and valuable knowledge. It was important for Toyota to

subsidize network knowledge-sharing activities early on to motivate

In the final phase, the PDA learning teams developed and

members to participate. The supplier association was the vehicle

strengthened multilateral ties between suppliers and facilitated the

through which links to suppliers were established and explicit

sharing of tacit knowledge among them. Today, suppliers have

knowledge was transferred. In that early stage, the connections

two primary motivations for participating. First, they now

appreciate how important it is, as a Toyota supplier, to keep up to

between suppliers were weak, and there were numerous holes

pace. They are aware that the profit-creating potential of past

because most suppliers did not have direct ties to each

productivity enhancements declines steadily, and they know they

are in a learning race with rival suppliers because business from

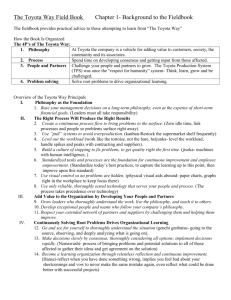

Ho w To yota Fac il itates Netwo r k Lea rn ing

Toyota is allocated based on relative performance improvements.

This creates strong incentives for suppliers to learn and improve

Toyota relies on three interorganizational processes — supplier

as quickly as possible. Second, suppliers now strongly identify

associations, consulting groups and learning teams — to faciliwith the network and feel obligated to reciprocate in the infortate the transfer of knowledge within its supplier network.

mation exchange so they begin to share knowledge more freely

with other members. This strengthens multilateral ties among

suppliers and creates subnetworks for knowledge sharing within

TOYOTA

the larger system. In this mature stage, multiple pathways exist for

transferring both explicit and tacit knowledge, and the amount of

tacit knowledge being transferred is substantial (whereas in the

initiation phase it was almost nonexistent).

SUPPLIER

ASSOCIATIONS

Gener

al sharing of

information,

including Toyota

policies and

widely applicable

best practices

CONSULTING

GROUPS

LEARNING

TEAMS

Inten

sive on-site

assistance from

Toyota experts

Work

shops and

seminars

Onsite sharing of

know-how

within small

groups of 6 to

12 suppliers

The Competitive Advantages

For manufacturing in the United States, Toyota now buys more

than 70% of its parts from U.S. companies. Consequently, the

company is increasingly using the same suppliers as its U.S. competitors, which raises an interesting question: How can Toyota

SPRING 2004 MIT SLOAN MANAGEMENT REVIEW 61

Evoluti on of Toyota Net wor k

In the early stages of a knowledge-sharing network, Toyota

establishes bilateral relationships with suppliers (left). At this

point, the supplier network resembles a hub (Toyota) with

many spokes. Later, the suppliers begin to form ties with

each other in nested subnetworks (right). These multilateral

rela-tionships greatly facilitate the flow of knowledge so that

members are able to learn much faster than rival, nonpartici pating suppliers.

INITIATION

Toyota

Suppliers

MATURE

Toyota

Suppliers

achieve a competitive advantage through these vendors? Traditional economic theory suggests that the only possible way is by

extracting lower unit prices based on greater relative bargaining

power.z In the United States though, Toyota has lower unit volumes than its U.S. competitors, placing the company at a disadvantage. But Toyota has been able to overcome that handicap and

has instead achieved competitive advantages with its U.S. suppliers by providing them with knowledge and technology to improve

their productivity for just their operations that are dedicated to

Toyota. The results of our survey of those vendors help illuminate

the reasons for Toyota’s success.

Compared with the Big Three (GM, Ford and DaimlerChrysler), Toyota has engaged in significantly more knowledgesharing activities with its U.S. suppliers. Toyota sent personnel to

visit the suppliers’ plants to exchange technical information an

average of 13 days each year versus six for the Big Three. As one

plant manager noted, “We have received a great deal of knowledge from Toyota.... We have learned about in-sequence shipping, kanban [a system for reducing inventory], one-piece

production and standardized work. We have even learned some

of Toyota’s HR-related training philosophy and methods.” The

plant managers surveyed were unanimous in their opinion that

Toyota provided more valuable assistance than their largest U.S.

customer despite the fact that they sold an average of 50% less

volume to Toyota.

The greater knowledge sharing has had a substantial effect.

From 1990 to 1996, the suppliers reduced their defects (in parts per

million) by an average of 84% for Toyota versus 46% for their

62

MIT SLOAN MANAGEMENT REVIEW SPRING 2004

largest Big Three customer. Similarly, the average supplier

slashed its inventories (as a percent of sales) by 35% in its

operations devoted to Toyota versus only 6% for its largest Big

Three customer. And suppliers increased their labor productivity

(sales per direct employee) by 36% for Toyota versus just 1% for

their largest Big Three customer. Furthermore, by 1996 the

suppliers had achieved 10% higher output per worker, 25% lower

inventories and 50% fewer defects in their manufacturing cells for

Toyota, as compared with what had been achieved for their largest

U.S. customer. These results are all the more amazing given that

the suppliers were manufacturing a similar component for a U.S.

customer within the same plant!

Sustaining the Advantages

If suppliers have achieved such significant improvements by

sharing knowledge with Toyota, why then don’t they utilize

that know-how for their other customers? In fact, one-third of

the U.S. suppliers in our study reported that they did transfer

the knowledge acquired from Toyota to manufacturing cells

devoted to their largest U.S. customer. But the remaining twothirds did not. Many plant managers reported that even when

they wanted to transfer knowledge to other manufacturing cells

in the same plant, they often couldn’t because of two types of

barriers: network constraints and internal process rigidities.

Network Constraints In some instances, plant managers reported

being unable to transfer knowledge because of a particular customer’s policies or other constraints. For example, one supplier

was required by its Big Three customer to use large containers,

approximately 4 feet by 6 feet and weighing 200 to 300 pounds

when filled. By comparison, Toyota had the supplier use smaller

containers, about 2 feet by 3 feet and weighing 40 pounds when

filled. This had a number of important ramifications. The manufacturing process using large containers required more floor

space, and the supplier needed to purchase forklifts and hire

forklift operators to move the containers. Not only were the large

containers unwieldy, they were also tougher to keep clean, which

affected product quality. Furthermore, the large containers made it

more difficult to label and sort products into a particular sequence

for production at the assembler’s facility. But the large containers

fit well into the Big Three assembler’s system (which also used

forklifts and a lot of floor space), so the customer wouldn’t allow

a change to a smaller size. Thus, the supplier was unable to

replicate the processes that it was using for Toyota.

Internal Process Rigidities Suppliers were much less likely to

transfer knowledge from Toyota to one of the Big Three when

the manufacturing cells for that customer had a high level of

automation or a large capital investment in heavy equipment.

Such internal process rigidities — large machines bolted or

Consider the significant price premiums that Toyota vehicles

cemented in place, trenches in the floor, utilities hardwired to

enjoy (relative to U.S. cars in the same class): an average of 9.7%

equipment and so on — increased the costs of transferring

for new cars and 17.6% for used ones.3 Higher quality is a major

knowledge. As one plant manager reported, “When you invest in

reason why Toyota vehicles can command such prices. The J.D.

automation, you do everything you can to run that job for as long

Power and Associates Initial Quality studies have found that

as you can. When you have to change a highly automated process,

between 1990 and 2000 Toyota cars had roughly 40% fewer probyou have a devil of a time. It just never works.” Internal process

lems (per 100 vehicles) than did autos from the Big Three.4 The

rigidities help explain why suppliers had relatively low rates of

total cost of the knowledge-sharing activities that have conproductivity improvement for their U.S. customers. Plant managers could not make the changes they

wanted, or they were forced to wait

until the customer terminated a vehicle

“We are not so concerned that our knowledge will spill over to

model before they could implement a

new process. Thus, at the very least,

competitors. By the time it does, we will be somewhere else.”

internal process rigidities created a

significant time lag. In contrast, Toyota’s production network has been

designed as a dynamic system with flexibility built directly into

tributed to the enhanced quality of Toyota vehicles was between

the manufacturing processes. Most machines, for example, are

$50 million to $100 million for the United States and Japan. That

on rollers so they can be moved easily to new locations.

amount might seem considerable, but it was relatively small for a

$100 billion company like Toyota, and it was certainly a wise

Other factors can also impede the transfer of knowledge to

production cells dedicated to Toyota’s rivals. A number of plant

investment that has more than paid for itself in increased profits

for the Japanese automaker.

managers refrained from even requesting a major change from a

U.S. customer because they perceived the approval process to be

The experience of Toyota strongly suggests that competitive

time consuming and difficult. Furthermore, significant changes

advantages can be created and sustained through superior

to a manufacturing cell often require considerable down time,

knowledge-sharing processes within a network of suppliers. We

which a customer might be unwilling to endure. Or the customer

believe those principles have broader applicability, for example, in

other types of alliance networks, including those with partners in

might refuse to accept the possibility that the new processes

might initially have bugs. According to the president of one supjoin ventures. In fact, establishing effective interorganizational

plier,“Sometimes it’s just not worth the risk to try something

knowledge-sharing processes with suppliers and partners can be

new if the customer isn’t supportive and involved. If you cause a

crucial for any company trying to stay ahead of its competitors. As

recall, or even if they think you caused a recall, it could put you

one senior Toyota executive observes, “We are not so con-cerned

out of business. And if you shut down their plant, they charge

that our knowledge will spill over to competitors. Some of it will.

you $30,000 a minute.

But by the time it does, we will be somewhere else. We are a

moving target.”

In summary, taking know-how learned from one customer

Indeed, Toyota’s dynamic learning capability, enabled

and applying it to another can be extremely difficult, mainly

through a network of knowledge sharing, might turn out to be

because knowledge is so context-dependent. But the ability to

transfer and adapt knowledge can, in and of itself, be a

the com-pany’s one truly sustainable competitive advantage.

competitive advantage. As Michio Tanaka, the general manager

in purchasing at Toyota, asserts, “The ideas behind the [TPS]

REFERENCES

have basically diffused and are understood by our competitors,

1. L. Chappel, “Toyota: Slash — But We’ll Help,” Automotive News 77

but the know-how regarding how to implement it in specific

(Sept. 16, 2002): 4.

factories and contexts has not. Toyota Group companies are

2. M. Porter, “Competitive Strategy” (New York: Free Press, 1980).

better at implementing the ongoing ... activities associated with

3. J.H. Dyer and N. Hatch, “Network-Specific Capabilities, Network

Barriers to Knowledge Transfers, and Competitive Advantage” (paper

the [TPS]. ... I think we are better at learning.”

The Bottom Line

The trickle-down benefits of knowledge sharing can be substantial. By transferring its know-how to suppliers, Toyota has helped

those firms greatly improve their performance, and this in turn has

generated tremendous competitive advantages for Toyota.

presented at the Strategic Management Society Conference, Orlando,

Florida, Nov. 7-10, 1998).

4. J.H. Dyer, “Collaborative Advantage” (New York: Oxford University

Press, 2000).

Reprint 45311. For ordering information, see page 1.

Copyright Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2004. All rights reserved.

SPRING 2004 MIT SLOAN MANAGEMENT REVIEW 63

MITSloan

Management Review

PDFs ■ Reprints ■ Permission to Copy ■ Back Issues

Electronic copies of MIT Sloan Management Review

articles as well as traditional reprints can be purchased

on our Web site: www.sloanreview.mit.edu or you may

order through our Business Service Center (9 a.m.-5

p.m. ET) at the phone numbers listed below.

To reproduce or transmit one or more MIT Sloan Management Review articles by electronic or mechanical

means (including photocopying or archiving in any

information storage or retrieval system) requires

written permission. To request permission, use our

Web site (www.sloanreview.mit.edu), call or e-mail:

Toll-free in U.S. and Canada: 877-727-7170

International: 617-253-7170

e-mail: smrpermissions@mit.edu

To request a free copy of our reprint catalog or

order a back issue of MIT Sloan Management

Review, please contact:

MIT Sloan Management Review

77 Massachusetts Ave, E60-100

Cambridge, MA 02139-4307

Toll-free in U.S. and Canada: 877 -

727-7170 International: 617-253-7170

Fax: 617-258-9739

e-mail: smr-orders@mit.edu