FR2010-21 Final Report AH/2004/046

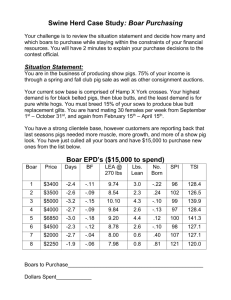

advertisement