Differential effect of predominant one party system versus two party

advertisement

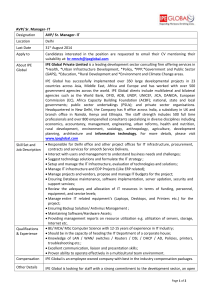

Social Network and Voting Behavior in reference to a differential effect of a multiparty versus a two-party system: With a Comparison between Japan and US Election data ELECTORAL SYSTEMS AND ELECTORAL POLITICS: Bangalore CSES Workshop & Planning Committee Meeting 2- 4 November 2006 Ken’ichi Ikeda The University of Tokyo Abstract In a comparative analysis of American and Japanese voting behavior, the effects of social networks on voting behavior and the expression of political opinion were investigated. Using an Interpersonal Political Environment (IPE) approach, which assumes that social networks form influential environments with respect to such behavior, a consistent pattern of influence via social networks was detected in both countries. A similar pattern is also observed with respect to voluntary expressions of opinion about politicians. : Further analyses on Japanese data assures that this IPE effect reflects voluntary judgment of voters. Then, the effect of social networks seems to be caused by the acceptance of viewpoint of others within IPE as a political reality (which helps voluntary decision to vote). : Effect was larger in the US than in Japan The difference is partly attributable to institutional difference between the US and Japan, specifically the political party configuration Interpersonal influence in U.S. Findings of interpersonal influence on voting patterns have been well established in the US (Lazarsfeld et al., 1948) The influence is more systematically investigated in recent studies using ‘social network batteries’ to measure daily interpersonal political communication (Huckfeldt & Sprague, 1995). Japanese Voting “Peculiarity” Japan is often described as having collectivistic culture, which means interpersonal influence is substantial. In this sense, the same pattern of interpersonal influence as in US could be observed. However, the meaning of influence might have been different. Previous studies of Japanese elections ; Voters are often described as passively mobilized to vote in traditional contexts Richardson (1991) points out that in Japanese elections in the 1970s, “people’s voting support is sought via mobilization of social networks and group affiliations by “influence communications”. “[These] communications are interpersonal and organizational communications, designed to directly mobilize and manipulate voting support through activation of personal obligations, feelings of deference, or other kinds of sentiment pertaining to specific ongoing social relationships that extend well beyond any given election campaign” (p. 339). Often attributed to factors that are peculiar to Japanese collectivistic culture. Is it true? Generalization and more Exploration of the mechanism of any similarities and differences is needed. Because, Decline of collectivism in Japan Japanese are no more collectivistic than Americans (Oyserman et al., 2002; Matsumoto, 1999) Huge structural changes in Japan From multi-member single nontransferable vote system to mixed but basically SMD system Beyond peculiarity contention, the micro-interpersonal structural effect on both Japanese and American voting behavior could be similar. In this context, I will analyze the interpersonal effects in Japan and US. The IPE effect as a hypothesis of network effect An individual is embedded in a network, which is composed of others who are connected to the given individual through ties. E D F We refer to this network as the IPE (Interpersonal Political Environment). A C B G Figure 1. IPE for A The IPE effect as a hypothesis of network effect Others in the network are individuals who not only surround A, but also form an environment that contributes to A’s social and political reality. Although others in the network form a collection of individuals, their product—that of the IPE they represent—is a collective entity. In an IPE in which A’s political discussants are all LDP supporters, there will be an information configuration that filters out most unfavorable information about the LDP. In this situation, the IPE promotes an LDP-favorable social reality for A. This effect is not caused by any one individual, for instance opinion leader, but is a collective result of A’s IPE. The IPE effect as a hypothesis of network effect This approach emphasizes the fact that others in the network are agents of a variety of information resources to A, and play an important part in constructing A’s social reality. IPE is more than an agent of information resources. Our social reality is a joint product of individual belief, collective support by others, and mass media information (Ikeda 1993, 1997), i.e. IPE is an essential part of our social reality. In this sense, people maintain their sense of reality collectively in their personal environment, including their voting behavior. Hypothesis 1: IPE effect In both the US and Japan, the higher the ratio of IPE of a specific Party X, the higher the probability that the respondent will vote for Party X. Effect of social network; Spontaneity (1) However, supposing “collective influence” of IPE does not mean that people are influenced by conformity pressure. The phenomenon which has not been well investigated but important focus in the context of interpersonal effect, i.e. spontaneity dimension: passiveness vs. activeness. Passiveness : The effect of network derives from a passive and conforming power mechanism. Activeness : Spontaneous influence acceptance by an informational or referent power mechanism. The latter was only emphasized by Putnam. Passive influence such as coercive power which makes people conform should be more focused on. In classical studies (Asch, 1951; Deutsch & Gerard, 1955), group influence has often been thought of as a result of passive and conforming pressure (even in the US context). Is it still true in the contemporary world? Effect of social network; Spontaneity (2) Passive vs. spontaneous distinction is especially consequential for actual democratic practices The conformity pressure could be a factor for the formation of the “dark side of social capital” It may restricts members of a given group to commit a specific behavior or subscribe to a specific political orientation, thus disturbing open discussion and making the members intolerant to non-conforming deviants. If the mechanism is spontaneous (informational or referent), the same concurrent seeking is interpreted quite differently Trust on others is essential here and it goes together with positive social capital Open discussion, and tolerance to heterogeneous ideas due to the lack of coercive power. Effect of social network; Spontaneity (3) As was shown, historically in Japanese society, social networks played negative roles in modernizing Japanese political attitude and behavior (Abe, Shindo & Kawato, 1990; Richardson, 1991). This claim presupposes that the group influence mechanism under Japanese society is by conformity enforcement, i.e. non-spontaneous power is the major engines, especially to mobilize people to vote some specific candidate. There seems to be a good reason, however, that this is not the case anymore due to the huge structural changes of the society in 1990 and after (as mentioned before). Let’s empirically check this point. Hypotheses and strategies on analyses (1) Hypo 2) Spontaneous effect hypothesis 2A) Spontaneous expression on PM Koizumi or Bush/Gore 調査票番号 Positive and negative open-ended responses on politicians; these are based on spontaneous cognitive process. If these spontaneous expressions are a positive function of the IPE's political color, IPE’s effect is not from conformity. Conformity pressure functions are only limited to the very situation under specific and concrete group pressure (voting situation). 0000000 0000001 0000002 0000003 0000004 0000006 入力欄 入力欄 Positive on PM Negative on PM わかりやすくしゃ べってるし、やら なければならな いこともやって る。 はぎれがいいと いうか、言うこと が明確 今のところあま り枠に縛られて いない。内政に 関しては、いい ところまではいく と思う。 改革すると言っ 切っている点 なんかパワーが ある。やる気が 見られる。 新しく構造改革 ということで経済 が良くなればい いと思う。 小泉内閣はいい けど、自民党の 中が変わってな いところ。 実行力はわから ない。 世界の中の日 本という立場で は、今の接し方 では危ういと思 う。 今のところ何も 変わっていない し、足並みがあ まりに揃ってい Hypotheses and strategies on analyses (2) Hypo 2) Spontaneous effect hypothesis 2B) Spontaneity of political participation (JP only) When conformity pressure is working: facilitates Ego’s campaign participation in accordance with the IPE’s political color, while oppressing participation in discordance with that political color Conformity pressure is a force that coerces human behavior in a specific direction which at the same time oppresses behavior going to the opposite direction. When spontaneous power is working; IPE facilitates political participation consistent with, but without suppressing opposing directions (i.e. tolerant). IPE is only providing information or a behavioral referent, which is adopted/chosen by ego spontaneously (This is not testable in voting behavior because of its trade-off nature). 2C) Controlling mobilization variable (JP only) Mobilization attempts often utilize traditional power of social network, i.e. conformity (as was old Japanese voting theories). If mobilization is predictive of vote and at the same time reduce the effect of IPE, spontaneity hypothesis will be in danger. Before testing Hypos: How we measure IPE? social network battery with using “name generators” Components of network: Japan-US % Number of others in the network Survey CNEP93 Country/Year Japan/93 JESII Japan/95 JESII JEDS2000 JESIII JESIII Japan/96 Japan/2000 Japan/2001 Japan/2001 Spouse + Political Significant Significant Significant frequent Political discussant + Definition of other other* other other contact other discussant spouse 0 34 28 33 7 30 11 1 35 27 26 20 28 41 2 17 20 20 9 20 23 3 8 25 21 64 11 14 4 5 11 12 5 2 Average number of other 1.2 1.4 1.3. 2.3 1.4 1.7 N 1333 2076 2299 1618 2061 2061 * The last one is a political discussant CNEP92 U.S. NES2000 U.S. Significant Political other* discussant 9 26 18 19 15 20 19 14 18 21 22 2.8 1.9 1318 1551 JP has less network members if it is significant others/ political discussants Relationship with net-other % Number of others in the network Survey CNEP93 JESII JESII JEDS2000 JESIII JESIII Country/Year Japan/93 Japan/95 Japan/96 Japan/2000 Japan/2001 Japan/2001 Relationship with other Spouse 31 34 33 34 28 40 Another immediate family member 13 13 13 7 14 11 A relative 4 4 5 10 5 4 A friend 24 24 18 35 18 15 A coworker 16 16 19 14 20 17 A neighbor 3 3 6 5 4 The same church The same leisure activity group 2 2 4 6 5 The same organization of group (the other group) 4 2 6 5 4 Other 1 1 2 1 0 Network N** 1620 2934 2969 3718 2946 3567 ** Number of paired data (Respondent and partner) CNEP92 U.S. NES2000 U.S. 17 33 37 17 10 9 - 14 29 27 15 8 - - 6 2890 3752 JP’s predominance of spouse and small number of neighbors Talk and guess on political matters Table1b Differences of others in the network by types of network battery (2) Survey Country/Year CNEP93 Japan/93 JESII Japan/95 JESII Japan/96 Significant Significant Definition of other other* other Amount of political discussion with other Max*** 15 8 34 37 32 42 Min 16 12 DK.NA. 3 2 Network N 1620 2934 *** Expression on max/min differs from survey to survey Guess of political orientation of other Party voted LDP 24 JSP/SDP 7 CGP 5 NFP DPJ JCP 2 New party 8 Other party 2 Don't vote 2 Independent DK.NA 51 Network N 1620 JEDS2000 JESIII Japan/2000 Japan/2001 Spouse + Significant frequent Political other contact other discussant 6 31 46 16 2 2969 Party voted 20 7 17 3 2 6 46 - Party voted 24 2 13 5 3 2 4 48 - 2934 2969 JESIII Japan/2001 Political discussant + spouse CNEP92 U.S. %表示 NES2000 U.S. Significant other* Political discussant 20 50 25 5 0 3752 24 53 22 1 0 2890 4 30 61 5 3718 21 60 17 2 2946 17 54 26 3 3567 21 1 2 2 1 0 24 48 - Party voted 31 2 6 4 2 1 54 - Party voted 31 2 6 4 2 1 55 - 3718 2946 3567 PID Party voted Party voted 40 38 Democrat 35 42 Republican 14 3 Third party 1 2 9 Don't vote 9 8 DK.NA 1 Net-other was under voting 3752 2890 talk (less) and less guess on politics in JP The test of hypotheses National sampling surveys with network batteries in both Japan and the US, particularly Japanese JES3 and US NES2000 data. Data source: JES3= 2001-2005 panel survey with 9 waves mainly focus on 2001 election with additional analyses on 2003 and after elections NES2000= pre-post survey on the Presidential Election 2000 JESIII 2001 House of Councilors Election [Pre FtF Survey] Target period: 19 July to 28 July, 2001 (29 July was the Election day Sample: 3,000 Japanese voters (over 20 years old) based on 2 stage stratified sampling Response rate: 2,061(68.7%) [Post Telephone survey] Target period: 1 August to 5 August, 2001 Sample: panel from the previous wave. Response rate: 1,253 (41.8% against the original sample; 60.8% against the 1st wave respondents; 791.% against those who provided their phone numbers) JESIII 2003 House of Representatives Election [Pre FtF survey] Period: 29 October to 8 November (9 Nov was the election day) Respondents Total Sample=3759, Response= 2162, Resp rate= 57.5% Panel 2334 1340 57.4% New Recruit 1425 822 57.7% (addition of sample by random sampling) [Post Ftf survey] Period: 13 November to 24 November Respondents Total Sample=3573 Response= 2268, Resp rate= 63.5% Panel 2356 1828 77.6% New Recruit 1217 440 36.2% Those who were accessible in both of the pre and post survey= 1769 Testing Hypothesis 1 (IPE effect on voting behavior) In the Japanese 2001 House of Councilors election, voters had two tickets Ordered logit analysis In the US Presidential Elections: Gore =0 and Bush =1 Logit analysis Japan Dependent Independent vars. variable Gender Age Education City size Knowledge LDP support DPJ support LDP support ratio by political discussants DPJ support ratio by political discussants U.S. variable IndependentDependent vars. Gender Age Education Knowledge Party Identification: Demo-Rep Democart support ratio by political discussants Republican support ratio by political discussants IPE effects are estimated by controlling demographic vars, and party ID (source of bias). By controlling party ID, we can reduce “projection” effect statistically. The result of the test on Hypothesis 1 Even by controlling for party ID variables, the results show a significant net effect of perceived votes. Table 2 Effect of net-other on vote Japan: 2001 House of Councilors Dependent variable Number of LDP vote Coef. 0.18 0.01 * -0.08 0.01 0.00 0.83 *** -0.06 Number of DPJ vote Coef. -0.17 0.02 * 0.03 0.07 0.04 -0.34 ** 0.92 *** Gender Age Education City size Knowledge LDP support DPJ support LDP support ratio by political discussants 0.78 *** -0.66 * DPJ support ratio by political discussants -1.15 *** 1.68 *** Cut point 1 1.98 2.66 Cut point 2 3.10 3.91 N 1011 1011 LR 331.23 232.13 P-value 0.00 0.00 Quasi R-square 0.16 0.18 P-value .05<p=<.1 +, .01<p=<.05 *, .001<p=<.01 **, p=<.001 *** US: 2000 Presidential vote Dependent variable Gender Age Education Knowledge Party Identification: Demo-Rep Democart support ratio by political discussants Republican support ratio by political discussants constant N LR P-value Quasi R-square 0=Gore 1=Bush Coef. -0.20 0.00 -0.07 -0.10 1.13 *** -0.97 * 2.21 *** -2.47 * 891 787.94 0.00 0.64 The result of the test on Hypothesis 1 The IPE effect hypothesis was supported in Japan The IPE effect in the US showed the same pattern as in Japan. Figure 2 Post hoc simulation of IPE effect Probability of vote for LDP or DPJ Probability of vote for Bush 2 vote 1 vote 0 vote 1 1 0.8 0.8 0.6 0.6 0.4 0.4 0.2 0.2 IPE 0 0 0 0 J 1 P 1 LDDPJ PJ r DPLDP DP r D L fo d fo d d nd an te 0 an te 0 an o o 1 1a v P v f f J J P LD lity o DP DP y o LD ilit i b b a a ob ob Pr Pr IPE m De d an an 0 5 p Re ep .2 R 1 em D d R Tie . 25 m 0 m De e D d n d an 1a 5 p .7 Re ep .75 Further data on Japan The IPE effect hypothesis (Hypothesis 1) was supported People vote consistently with the net-others’ perceived votes. Table 1 IPE effect on votes year 2001 Dependent variables LDP vote DPJ vote coef. coeff. Gender 0.28 * -0.18 Age 0.01 + 0.02 * Education -0.05 0.03 Years of residence 0.17 * -0.03 Megalopolis vs. Small Town 0.01 0.06 Knowledge 0.00 0.06 * LDP support 0.83 *** -0.37 ** DPJ support -0.08 0.96 *** LDP-IPE ratio 0.86 *** -0.59 * DPJ-IPE ratio -1.08 * 1.73 *** cutpoint 1 2.73 *** 2.71 *** cutpoint 2 3.89 *** 3.99 *** 1164 1164 N 0.17 0.19 Pseudo R2 p value .05<p=<.1 +, .01<p=<.05 *, .001<p=<.01 **, p<.001 *** year 2003 LDP vote coef. 0.18 0.01 + -0.02 0.17 ** 0.06 * -0.01 0.75 *** -0.63 *** 1.02 *** -2.13 *** 2.12 *** 3.63 *** 1510 0.25 Year 2004 DPJ vote coeff. -0.33 * -0.01 * 0.05 -0.04 -0.04 0.03 -0.24 ** 1.02 *** -0.52 ** 1.95 *** -0.73 0.44 1510 0.20 LDP vote coef. -0.09 0.01 -0.04 0.23 *** 0.07 * -0.13 + 0.92 *** -0.81 *** 1.06 *** -0.86 * 2.41 *** 3.58 *** 1512 0.28 year 2005 DPJ vote coeff. -0.05 0.00 0.13 * -0.07 0.03 0.07 -0.20 ** 1.13 *** -0.31 1.47 *** 0.51 1.54 ** 1512 0.19 LDP vote coef. -0.22 -0.01 0.03 0.09 0.02 -0.03 + 0.88 *** -0.30 ** 1.37 *** -1.04 *** 0.32 1.81 ** 1230 0.26 DPJ vote coeff. 0.24 + 0.00 0.01 -0.10 0.00 -0.01 -0.21 ** 0.91 *** -1.18 *** 1.56 *** 0.35 1.42 * 1230 0.24 Testing Hypothesis 2A (the spontaneity effect of discussants) Dependent Variables; Japan: Open-ended evaluations on the Koizumi cabinet. We counted the number of positive and negative responses. 88% of the voters gave one or more positive answers 36% did so on negative comment More than 30% gave two or more positive answers, while 6% gave two or more negative answers. US ; Four open-ended answers Positive and negative statements about the candidates Gore and Bush. More numerous than in the Japanese survey, Around 30% gave two or more answers. The result testing for Hypothesis 2A Table 3 Effect of IPE on the political opinion expression Japan: open-ended expressions on the Koizumi Cabinet No of positive Dependent variables responses Coef. Gender 0.39 *** Age 0.00 Education -0.12 + City size -0.03 Knowledge 0.07 *** LDP support 0.10 + DPJ support 0.08 Cabinet support 0.47 *** ratio by political discussants cut point 1 cut point 2 cut point 3 -1.53 1.43 3.26 US: open-ended expressions on the Presidential Candidates No of negative responses Coef. -0.29 * 0.00 0.25 *** -0.06 * 0.06 *** -0.28 *** 0.04 -0.42 *** 0.24 2.64 N 1332 1362 LR 47.97 117.87 P-value 0 0.00 Quasi R-square 0.0165 0.05 p value .05<p=<.1 +, .01<p=<.05 *, .001<p=<.01 **, p=<.001 *** Dependent variables Gender Age Education Knowledge Party Identification: DemoRep Democart support ratio by political discussants Republican support ratio by political discussants cut point 1 cut point 2 cut point 3 cut point 4 cut point 5 N LR P-value Quasi R-square No of positive responses on Gore Coef. 0.19 0.01 + 0.10 ** 0.21 *** -0.46 *** 0.68 *** -0.68 ** 0.79 1.73 2.59 3.45 4.21 1115 467.51 0 0.1367 No of negative responses on Gore -0.26 * -0.01 + 0.10 ** 0.27 *** 0.40 *** 0.11 0.86 *** 2.31 3.35 4.35 5.36 6.25 1116 410.75 0 0.1215 No of positive responses on Bush -0.01 0.01 0.04 0.12 ** 0.55 *** -0.16 0.85 *** 2.86 3.84 4.84 5.65 6.40 1115 515.08 0 0.1573 No of negative responses on Bush -0.23 + 0.00 0.18 *** 0.21 *** -0.42 *** 0.51 ** -0.44 * 0.99 1.97 2.86 3.74 4.48 1114 390.89 0 0.1155 The result testing for Hypothesis 2A Japan: Without discussants’ support, two or more positive comments were made by only 25% of the voters, whereas with full discussants’ support, the number rose by 10%. The reverse was true for negative comments; 42% and 33% respectively, resulting in a difference of nine percentage points. In total, there was a difference of 19 percentage points between the effect in the positive and negative responses. Figure 3 Posthoc simulation of open-ended responses on Prime Minister Koizumi 100% 80% 60% 2 or more 1 0 40% 20% 0% Min・Positive Max・Positive Min・Negative Max・Negative Ratio of net-others Cabinet support The result testing for Hypothesis 2A Figure 4 Posthoc simulation of open-ended responses on Presidential Candidates Positive Gore comments Positive Bush comments 100% 100% 80% 80% 20% ro ng St St 100% 100% 80% 80% Re pu bli ca n ro ng In de pe nd en t 0% oc ra t Re pu bli ca n 20% St St ro ng In de pe nd en t oc ra t 0% 40% De m 20% 60% ro ng 40% five four three two one no response St 60% De m five four three two one no response Negative Bush comments Negative Gore comments ro ng Re pu bli ca n 0% In de pe nd en t Re pu bli ca n St St ro ng In de pe nd en t ro ng De m oc ra t 0% 40% oc ra t 20% 60% De m 40% five four three two one no response ro ng 60% St If discussants were 100% Democrat, the probability of zeropositive comment for Gore was only 17%, but if discussants were 0% Democrat, the probability was 71. The corresponding probability for Bush was 25% versus 76%. Both of the cases had more than 50 percentage point differences. five four three two one no response Further data on Koizumi Even after controlling verbal fluency (knowledge) and political bias (party support), IPE effect survived consistently. Support Hypothesis 2A(2001-2005). Table 7 IEP effect on spontaneous expression on the Cabinet year 2001 year 2003 Year 2004 year 2005 N of positive N of negative N of positive N of negative N of positive N of negative N of positive N of negative Dependent variables expression expression expression expression expression expression expression expression coef. coeff. coef. coeff. coef. coeff. coef. coeff. Gender 0.46 *** -0.19 0.14 -0.11 0.23 * -0.12 -0.19 0.22 + Age 0.00 0.01 0.01 0.01 * 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.01 ** Education -0.13 * 0.29 *** 0.17 * 0.16 * 0.08 0.26 *** 0.22 ** 0.38 *** Years of residence -0.03 -0.08 + -0.08 -0.11 0.01 0.02 0.07 0.06 Megalopolis vs. Small Town -0.01 -0.04 -0.01 -0.04 0.00 0.03 -0.03 -0.05 + Knowledge 0.08 *** 0.06 ** 0.04 * 0.09 *** 0.14 * 0.26 *** -0.01 0.07 *** LDP support 0.18 *** -0.25 *** 0.30 *** -0.01 0.40 *** -0.17 ** 0.27 *** -0.12 + DPJ support 0.16 * 0.05 0.08 0.34 ** -0.08 0.21 ** 0.08 0.24 ** Cabinet support IPE ratio 0.47 *** -0.40 ** 0.91 *** -0.58 *** 1.24 *** -0.83 *** 1.20 *** -0.58 *** cutpoint 1 -1.22 ** 0.51 0.98 + -0.14 0.65 -0.18 0.48 1.21 * cutpoint 2 1.70 *** 2.91 *** 3.40 *** 2.52 *** 3.01 *** 2.30 *** 3.21 *** 3.80 *** cutpoint 3 3.45 *** 4.93 *** 5.15 *** 4.15 *** 5.10 *** 4.20 *** 5.05 *** 5.58 *** 1534 1570 1321 1321 1399 1399 1250 1250 N 0.02 0.05 0.04 0.05 0.07 0.05 0.06 0.05 Pseudo R2 p value .05<p=<.1 +, .01<p=<.05 *, .001<p=<.01 **, p<.001 *** Campaign participation as dependent variable; spontaneity effect (H2B) Campaign-related participation activities as dependent variables. The stronger LDP-IPE, the more voters are inclined to join LDP campaign related activities. The reverse effects do not appear, i.e. DPJ-IPE does not decelerate participation for LDP. The same is true for DPJ-IPE. H 2b was supported strongly in this test. Table 4 IPE Effect on campaign participation year 2001 participation participation Dependent variables for LDP for DPJ coef. coeff. Gender -0.69 ** -0.99 ** Age 0.02 + 0.01 Education 0.21 -0.25 Years of residence 0.03 -0.02 Megalopolis vs. Small Town 0.01 0.03 Knowledge 0.05 0.05 LDP support 0.42 ** -0.33 * DPJ support -0.07 0.45 * LDP-IPE ratio 0.86 *** -0.28 DPJ-IPE ratio 0.59 1.31 * -4.11 *** -1.92 constant 1164 1164 N 0.11 0.12 Pseudo R2 p value .05<p=<.1 +, .01<p=<.05 *, .001<p=<.01 **, p<.001 *** year 2003 participation participation for LDP for DPJ coef. coeff. -0.28 -0.58 * -0.01 -0.01 -0.04 0.00 0.39 ** 0.17 0.11 + -0.06 0.04 0.07 * 0.77 *** 0.01 -0.14 0.66 *** 1.65 *** 0.23 0.26 2.04 *** -6.70 *** -3.18 ** 1622 1622 0.22 0.20 Year 2004 participation participation for LDP for DPJ coef. coeff. -0.48 + -0.08 0.00 0.00 0.09 0.19 0.19 0.24 0.09 0.03 0.05 0.33 * 0.74 ** 0.11 -0.04 0.84 *** 1.85 *** 0.47 0.50 2.13 *** -6.25 *** -6.56 *** 1721 1721 0.22 0.22 year 2005 participation participation for LDP for DPJ coef. coeff. -0.18 -0.58 + 0.01 -0.01 0.12 0.02 0.00 0.21 0.09 0.17 * 0.05 0.02 0.86 *** 0.39 0.45 + 1.23 *** 1.36 *** -0.63 -0.19 0.78 * -6.28 *** -5.44 *** 1300 1300 0.18 0.23 Campaign participation as dependent variable (H2B) Do these spontaneous effects survive even after controlling mobilization variables? Mobilization attempts are effective throughout the 4 cases, but still spontaneous effect remains valid (based on the post-hoc simulation of the equations with mobilization vars to Table 4 results (1 page before). Figrure 2 Post-hoc simulation on the effects of IPE versus mobilization year 2003 year 2001 Participation for LDP Participation for DPJ 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% 0% 50% 100% Support of IPE no Participation for LDP Participation for DPJ 35% 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% 0% yes 50% 100% Support of IPE mobilization attempt no yes mobilization attempt Effects for congruent cases; LDP for LDP & DPJ for DPJ year 2005 year 2004 Participation for LDP Participation for DPJ 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% 0% 50% Support of IPE 100% no yes mobilization attempt Participation for LDP Participation for DPJ 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% 0% 50% Support of IPE 100% no yes mobilization attempt Effect of mobilization on vote (H2C) Mobilization in terms of solicitation to vote for some specific party has been thought of in Japanese context as the main factor. We added mobilization variables on to the models in Hypo 1 The results show that Japanese voting behavior for conservative party is no more the results of conformity pressure. Table 6 Adding mobilization variables to predict votes year 2001 Dependent variables LDP vote DPJ vote coef. coeff. Gender 0.28 * -0.17 Age 0.01 0.02 * Education -0.06 0.04 Years of residence 0.16 * -0.03 Megalopolis vs. Small Town 0.00 0.07 Knowledge -0.01 0.06 * LDP support 0.84 *** -0.37 ** DPJ support -0.07 0.94 *** Mobilization attempt from LDP 0.15 * -0.14 Mobilization attempt from DPJ -0.03 0.22 + LDP-IPE ratio 0.84 *** -0.55 * DPJ-IPE ratio -1.11 * 1.70 ** cutpoint 1 2.65 *** 2.83 *** cutpoint 2 3.81 *** 4.12 *** 1164 1164 N 0.18 0.20 Pseudo R2 p value .05<p=<.1 +, .01<p=<.05 *, .001<p=<.01 **, p<.001 *** year 2003 LDP vote coef. 0.18 0.01 + -0.01 0.17 * 0.06 * -0.01 0.75 *** -0.62 *** 0.15 + -0.15 1.00 *** -2.13 *** 2.13 *** 3.64 *** 1510 0.25 Year 2004 DPJ vote coeff. -0.33 * -0.01 * 0.05 -0.04 -0.04 0.03 -0.24 ** 1.02 *** -0.13 0.09 -0.50 ** 1.95 *** -0.71 0.47 1510 0.20 LDP vote coef. -0.11 0.01 -0.04 0.22 *** 0.08 ** -0.13 + 0.92 *** -0.81 *** 0.15 -0.41 ** 1.06 *** -0.84 * 2.39 *** 3.58 *** 1512 0.28 year 2005 DPJ vote coeff. -0.05 -0.01 0.13 * -0.07 0.03 0.07 -0.20 ** 1.14 *** -0.01 0.51 *** -0.34 + 1.42 *** 0.53 1.57 ** 1512 0.20 LDP vote coef. -0.23 + -0.01 0.04 0.08 0.02 -0.03 + 0.89 *** -0.30 ** 0.05 -0.18 1.38 *** -0.99 *** 0.31 1.81 ** 1230 0.26 DPJ vote coeff. 0.25 + 0.00 0.02 -0.10 -0.01 -0.01 -0.21 * 0.91 *** 0.06 0.27 * -1.22 *** 1.48 *** 0.38 1.45 * 1230 0.24 Conclusion on spontaneity Spontaneity effect hypothesis (H2) Clearly well supported. IPE push up voluntary comments on the PM or Presidential candidates as well as political participation in line with the IPE. Also the effect of IPE on political participation was not suppressive on incongruent participation with the IPE color. These findings were strengthened when we controlled the mobilization variable. The power process working in IPE is not conformity pressure, but more voluntary in nature. All in all, people behave under the high influence of interpersonal environment, but it is not through the conformity mechanism, which has been supposed to be the main interpersonal force in Japanese political behavior for long time. Their behavior and attitude are constructed through a more voluntary and spontaneous basis, which is a good news for Japanese democracy and social capital theory. Comparison of the patterns between Japan and the US Go back to Hypo 1 and see the difference between the countries. The overall direction of the IPE effect was consistent in both countries. However, the effect size was much larger in the US. Figure 2 Post hoc simulation of IPE effect Probability of vote for LDP or DPJ Probability of vote for Bush 2 vote 1 vote 0 vote 1 1 0.8 0.8 0.6 0.6 0.4 0.4 0.2 0.2 IPE 0 0 0 0 J 1 P 1 LD PJ PJ r DP DP DP fornd D dL d D e fo nd L n n e ot 0 a 1 a vot 0 a 1a fv P f J J P LD lity o DP DP y o LD ilit i b b a a ob ob Pr Pr IPE p Re 0 m d an p Re De .25 an 1 d m De e .25 m 0 e m De nd D d a n a 1 .75 Rep p . 75 Re Ti RQ Institutional difference (two-party system vs. multi-party systems) 1 [Institutionalized visibility problem] The difference between the Japanese and American data is attributable to the difference between the two-party system and the multi-party system with one dominant and other smaller parties? Limit the districts where the number of candidates receiving most of the votes was equal to the number of seats plus one. : Close competition occurs when the number of popular candidates is slightly higher than the number of seats in the given district. This makes the competitive parties highly visible, i.e. US-like institutional context arises. RQ Institutional difference (two-party system vs. multi-party systems) 2 We selected competitive 22 districts out of 47 : Mt 80% of votes went to seat+1 (with DPJ candidate) (test 1) In these ‘competitive’ districts, as the substantial competition increased the visibility of the candidates, the IPE effect would be larger than when the same analysis was carried out for all respondents? (test 2) To limit the districts where only one seat was being contested, and two candidates received 80% of the vote (More comparable to the American situation). In both of the two tests, we changed the dependent variable slightly. Because we analyzed the effect of seat competitiveness on a district level, we only focused on the district vote (removed PR vote). RQ Institutional difference (two-party system vs. multi-party systems) Table 4 Tests on the competitiveness effect The results were clear. As Table 4 shows, in these two types of tests, the IPE effect on the LDP vote or DPJ vote was larger in the competitive districts than in the less competitive ones test 1 IPE Competitive Non competitive Probability of vote for LDP 0.22 0.19 LDP 0 and DPJ 1 0.32 0.27 0.44 0.36 0.57 0.47 LDP 1 and DPJ 0 > Probability of vote for DPJ DPJ 0 and LDP 1 DPJ 1 and LDP 0 test 2 0.05 0.12 0.24 0.44 > 0.04 0.08 0.17 0.31 Competitive Non competitive IPE Probability of vote for LDP 0.31 0.19 LDP 0 and DPJ 1 0.45 0.27 0.60 0.36 0.73 0.47 LDP 1 and DPJ 0 > Probability of vote for DPJ DPJ 0 and LDP 1 DPJ 1 and LDP 0 0.04 0.16 0.47 0.79 > 0.04 0.09 0.18 0.33 RQ Institutional difference 2003 result (The 2003 election was for H. of Representative Election, i.e. SMD is smaller). The results were clear again. As Table shows, in this test, the IPE effect on the LDP vote or DPJ vote was larger in the competitive districts than in the less competitive ones. • competitive=more than 88% vote for the top 2 candidates in the single seat district (not PR) comptetitive less_competitive Probability of vote for LDP IPE LDP 0 and DPJ 1 0.07 0.06 0.21 > 0.17 0.49 0.40 LDP 1 and DPJ 0 0.78 0.68 Probability of vote for DPJ DPJ 0 and LDP 1 0.12 0.39 > 0.75 DPJ 1 and LDP 0 0.93 0.15 0.36 0.63 0.84 Discussion and conclusion for RQ Further analyses revealed that whether politics is organized around a two-party or multi-party system with small parties may well effect the impact of local personal political discourse. It was particularly revealing that Japanese electoral districts that in some respects mimic a US-type two-party system showed a stronger IPE effect on LDP voters as well as DPJ voters. [Other analyses (not shown) prompted by the research questions suggested that political cultural interpretations are not viable]. Discussion and conclusion In conclusion, the analyses showed differences in the effect of IPE, the direction of which contradicts the collectivism interpretation of Japanese political behavior. These differences may be largely attributable to institutional difference between the US and Japan, specifically the political party configuration (the two-party system versus the multi-party system with small parties). Institutional context could be very consequential. Context change makes party competition different, which in turn changes the power of IPE on vote. Japanese Electoral system change (from Multi-member single nontransferable vote system to SMD dominant system) may have increased the IPE influence.