IELTS test review educ 8540

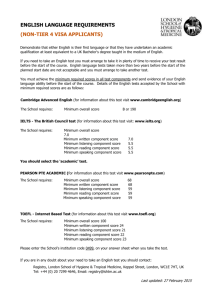

advertisement

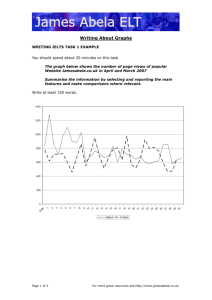

Running head: IELTS: A TEST REVIEW IELTS: A Test Review Patrick Dane Carson EDUC 8540: Language Assessment Kathleen Bailey, Ph.D. October 2, 2013 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 2 “Research in reading, like testing more generally, be likened to opening Pandora’s box. Once it is unlocked a vast array of questions clamour to be answered, some of which will require detailed intensive study on specific areas.” – Weir, 2009 Like testing generally, reviewing a test such as the English Language Testing System (IELTS), be likened to opening Pandora’s box. Once the specimen materials, handbook, and guidelines for testing and admissions personnel have been opened, a vast array of questions clamor to be answered, many of which require further, detailed, and intensive investigation. With the box now open, this review presents the International English Language Testing System with the objectives of: 1) painting a general picture of the test (history, test development, reliability, pricing, etc.); 2) shedding light upon test administration (how does it work, clarity of instructions, worthiness of effort); 3) reviewing the scoring system (how scores are derived/reported, score interpretation, etc.); 4) analyzing the IELTS in light of Swain’s four principles, and Wesche’s four components. The International IELTS is a high-impact test (micro/macro levels) available in two versions (Academic or General Training) depending on a test takers aims. This review investigates the Academic Test format of the IELTS which consists of listening, speaking, reading, and writing components (all candidates take the same listening and speaking components but different reading and writing components according to format) (IELTS, 2013a). The IELTS is recognized as the world’s most widely used criterion-referenced, high-stakes English language proficiency test, for higher education and immigration. With more than two million tests taken in 2012, at 900 testing locations, available for an in-country fee, in more than 130 countries, the IELTS has been a success (IELTS, 2013a). Cost varies per testing location (e.g. $205.00 in San Francisco) and includes a central (UCLES, The British Council/IELTS Australia) and local (test center) fee to cover all parties costs (UCLES, 2001, p. 17). IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 3 Considering the IELTS popularity, it is not surprising that with an ever-increasing international student population, that “there has been a corresponding increase in the use of the language test to screen applicants for language ability” (Green, 2007, p. 75) who desire to study in English-speaking universities or institutions of higher and further education. Among tertiary institutions around the world, the IELTS is intended “to find out whether candidates are ready to study or train in the medium of English” (Wallace, 1997, p. 370) and is accepted as evidence of English language proficiency by over 8,000 organizations worldwide (IELTS, 2013a). The IELTS, which is owned by the “University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate (UNCLES), The British Council and IDP Education Australia” (UCLES, 2001, p. 2) is the most widely recognized test of English for academic purposes in the UK and, although requirements differ by institution, universities will typically require a score of 6 or 7 on the nine band IELTS scale for unconditional entry (Green, 2007, p. 76). History In 1980, The British Council replaced the English Proficiency Test Battery (EPTB) which, at that time, had been in been in operation for fifteen years, with a new test in response to changes in language teaching theory, language learning, and developments in language testing. The new test was called the English Language Testing Service (ELTS), and was introduced into the overseas student recruitment operation of The British Council (UCLES, 2001, p. 6). The ELTS test offered six modules covering five areas of study of UK tertiary and one general module. The six modules were: Life Sciences, Social Studies, Physical Sciences, Technology, Medicine, and General Academic. From 1980 to 1989 the ELTS test format remained unchanged, but out of concern for practical difficulties with the administration of the test, The British Council had good reason to IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 4 change the test. In 1987, The British Council and UCLES commissioned Edinburgh University to perform validation study (UCLES, 2001, p. 6). Following the report of the ELTS Revision Project, a consensus was reached to broaden the international participation of the project. At that time, the International Development Program of Australian Universities and Colleges (IDP), currently known as IDP Education Australia, joined The British Council and UCLES in an international partnership to revise the test (UCLES, 2001, p. 6). The revision team recommended that the test should be simplified and shortened which led to the reduction of six to three subject modules, and the establishment of the General Module. The result of the revision was called the IELTS which became operational in 1989 (UCLES, 2001, p. 6). Beginning in 1989 IELTS test takers “took two non-specialized modules, Listening and Speaking, and two specialized modules, Reading and Writing. The non-specialized modules tested general English while the specialized modules were intended to test skills in particular areas suited to a candidates chosen course of study” (UCLES, 2001, p. 7). By 1995 the popularity of the IELTS had significantly increased and in response to developments in applied linguistics, measurement, and teaching practices, the test was once again revised in April 1995. Accordingly to UCLES, the following revisions enhanced the security and administration of the IELTS: The field-specific Reading and Writing Modules A, B, and C were replaced with ONE Academic Reading Module and ONE Academic Writing Module. Details of the research behind this change to the test design can be found in Clapham (1996) who concluded that the different subject modules did not appear justified in terms of accessibility to specialists. In addition, the thematic link between the reading and writing act ivies was also removed to avoid consuming the assessment and reading ability with that of writing ability. General Training Reading and Writing Modules were brought into line with the Academic Modules in terms of timing allocation, length of written responses, and reporting of scores. The difference between the Academic and General Training Modules is in the nature of the micro-skills tested not in the scales of ability. IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 5 Measures were introduced to gather data on test performance and candidate background so that issues of fairness relating to test use and users could be more effectively monitored. (2001, p. 7). In 1998 a project to revise the Speaking Test was launched and the revised IELTS Speaking Test was introduced in July of 2001. In 1997, a computerized version of the IELTS (CBIELTS) was launched in line with the commitment of the IELTS partners to respond to developments in technology and test development industry. Most recently, in January of 2005, new assessment criteria for the Writing Test were implemented (IELTS, 2013a). The current IELTS retains many features of the 1980 ELTS, although certain features, such as the link between theme and content papers have not survived the revisionary process. Nonetheless, the distinction between the Academic Test and the General Test has remained unchanged and is likely to be an everlasting feature of the International English Language Testing System. Description of the Listening Section of the IELTS The listening portion of the IELTS is the first component completed by a candidate. This module is 30 minutes in length and includes recorded monologues and conversations that require test takers to mark their answers while simultaneously listening to the stimuli. The IELTS listening module1 “comprises four sections that evaluate test takers’ ability to understand spoken English in different contexts” (Aryadoust, 2012, p. 43). Sections one and two “evaluate comprehension of everyday conversation, and sections 3 and 4 assess comprehension of academic discourse” (Aryadoust, 2012, p. 43). Section one exposes candidates to a conversation and “tests their understanding of specific and factual information; section 2 has the same assessment objective as section 1, but the stimulus is a short radio talk or an excerpt from a monologue” (Aryadoust, 2012, p. 43). Section 1 See Appendix A for sample Listening materials IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 6 three is a “conversation which involves negotiation of meaning [and] listening for specific information, attitudes, and speakers’ opinions” (The University of Cambridge ESOL Examination Syndicate, n.d.) in an academic context. Section four, has the same assessment objective as section 3, but the stimulus is an academic monologue. Each section contains ten test items, which, according to Aryadoust, fall into seven types: “(a) forms/notes/table/flow-chart/summary completion, (b) multiple-choice questions (MCQs), (c) short-answer questions, (d) sentence completion, (e) labeling a diagram/plan/map, (f) classifying, and (g) matching” ( 2012, p.43). In the listening module, the multiple choice questions do not require candidates to generate the correct answer on their own, but in item types C and item type D, test takers must produce their own response to answer items of that format. Description of the Reading Section of the IELTS The Reading Module of the IELTS2 is the second component completed by test takers. The Academic Reading Module is designed to assess a candidates reading ability to understand texts that they are likely to encounter in English-medium colleges and universities (UCLES, 2001, p. 10). As well, the Academic Reading Module contains 40 questions pertaining to reading passages which range between 2,000 and 2,750 words in length (UCLES, 2001, p. 10). Candidates have 60 minutes to complete the Academic Reading test which requires “testtakers to complete notes, summaries, and a range of iconic, presentations (diagrams, flow-charts, tables) using what they have read” (Weir et al, 2009, p. 104). Furthermore, candidates are also required to “identify information in the text, identify writers’ views or claims, and summarize paragraphs or text sections” (Weir et al, 2009, p. 104). A variety of texts are used from magazines, journals, books and newspapers, which are intended for a non-specialist audience (UCLES, 2001, p. 10). The texts utilized in the Academic 2 See Appendix B for samples of the IELTS reading module IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 7 Reading test are considered to be topics of “general academic interest” that “deal with issues which are intrinsically interesting, recognizably appropriate and accessible to candidates entering postgraduate or undergraduate courses” (UCLES, 2001, p. 10). The IELTS Academic Reading test appears to be multi-dimensional in construct which suggests that it measures a range of reading skills. Description of Writing Section of the IELTS The Academic Writing Module3 is a direct test of writing “in which tasks are communicative and contextualized for a specific audience, purpose, and genre” (Uysal, 2009, p. 315). Candidates are provided sixty minutes in which they must complete two tasks. The first writing task should consist of at least 150 words, and the second writing task should consist of at least 250 words (UCLES, 2001, p. 11). There is no choice of topics, however IELTS maintains “the topics are of general interest and require no subject-specific knowledge of the candidates” (UCLES, 2001, p. 11). The Academic Writing Module assesses writing ability appropriate to educational contexts. Candidates are tested on their ability to carry out different tasks which require appropriate vocabulary, grammar, content, and structure choice, while demonstrating audience awareness and overall communicative effectiveness (UCLES, 2001, p. 11). The Academic Writing test is designed “to provide sufficient accessible input so as to elicit a suitable sample of writing for assessment purposes” (UCLES, 2001, p. 11). The University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate summarizes the Academic Writing test as follows: Task 1candidates are asked to look at a diagram or table, and to present the information it contains in their own words. Depending on the type of input, candidates are assessed on their ability to: organize, present and sometime compare data; describe the stages of a process or procedure; describe an object or event or sequence of events; explain how something works. 3 See Appendix C for samples of the Academic Writing test IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 8 Task 2 candidates are presented with a point of view, argument or problem and are assessed on their ability to: present a problem; present and justify and opinion; compare and contrast evidence, opinions and implications; evaluate and challenge ideas, evidence or an argument (UCLES, 2001, p. 11). Description of the Speaking Section of the IELTS The Speaking Module4 is a test of speaking in the context of general English proficiency appropriate to educational, training, and social contexts. It is designed to measure linguistic and communicative skills needed for effective oral communication (UCLES, 2001, p. 12). In the Speaking test, a candidate will “have a discussion with a certified Examiner. It is interactive and as close to a real-life situation as a test can get” (IETLS, 2013a). The test is comprised of three parts and can range from 11 to 14 minutes in length. In Part 1, candidates answer questions about themselves, their family, interests, and related topics. In Part 2, candidates are given a verbal prompt on a card and asked to speak to a topic of personal relevance. Candidates are given one minute of preparation time before they are required to speak for one to two minutes Once the candidate has completed their turn, the examiner then asks one or two rounding-off questions (UCLES, 2001, p. 12). In Part 3, the candidate and examiner discuss more abstract issues relevant to the topic prompt in Part 2. Part three discussions last four to five minutes (UCLES, 2001, p. 12). All interviews are audio recorded to provide a record of the test takers performance which is rated for “Fluency and Coherence, Lexical Resource, and Grammatical Range and Accuracy” and Pronunciation (Carey et al., 2010, p. 205). There are three parts to the Academic Speaking test, each of which fulfills a specific function in terms of assessing patterns of interaction, task input, and candidate output (IELTS, 2013a). 4 See Appendix D for Speaking Test samples IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 9 Scoring System The IELTS is a secure test designed to assess English language proficiency. IELTS adheres to a detailed code for test delivery to candidates which safeguards against identity fraud. Two parts of the test are double marked, examiners are certified based on assessment standards, and every test version is different so no candidate can ever sit the same test twice. Furthermore, the British Council, IDP, and UCLES have strict protocols for all aspects of test design, delivery, and administration (IELTS, 2013d) to ensure test security. There is no “pass or fail” in the IELTS, rather test takers are graded on their performance using scores ranging from 1 to 9 for each part of the test (IELTS, 2013b). Thereafter, the Listening, Reading, Writing, and Speaking results “then produce an overall Band Score5” which can be reported in whole and half bands ranging from one to nine. The overall band score provide descriptive synopsis of the candidate’s linguistic ability (IELTS, 2013b). However, “how these descriptors are turned into band scores is kept confidential” (Uysal, 2009, p. 315). In terms of how overall Band Scores are reported, “for the avoidance of doubt, the following rounding convention applies: if the average across the four skills ends in .25, it is rounded up to the next half band, and if it ends in .75, it is round up to the next whole band” (IELTS, 2013a). For example, if a candidate is marked 6.5 for Listening, 6.5 for Reading, 5.0 for Writing, and 7.0 for Speaking, the candidate would receive an Overall Band Score of 6.5 (25 ÷ 4 = 6.25 = Band 6.5) (IELTS, 2013b). The IELTS Listening and Reading Modules each contain 40 items which are awarded one mark per correct answer (40 being the maximum raw score possible). Band scores are given to test takers on the basis of their raw score6. The IELTS 5 See Appendix E for Band Score descriptors See Appendix F for a table which indicates the mean raw score achieved by candidates of various levels in each of the Listening, Academic Reading, and General Training Reading tests for an indication of the number of marks required for a particular band score. 6 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 10 test results are available thirteen days after the test is completed and each candidate is entitled up to five copies of the Test Results Form (TRF); additional copies of the TRF are available at cost. In terms rater reliability, which Bailey (1998) defines as “the consistency with which raters use a scoring system” (p. 247), IELTS accounts for intrarater reliability (“which is determined by having the same person evaluate the same data on two different occasions and comparing the results to see how similar they are” (Bailey, 1998, p. 247)), by training test markers to “understand the IELTS marking policy” which requires that they “demonstrate that they are marking to standard before they are allowed to mark” (IELTS, 2013a). Furthermore, IETLS Markers are retested every two years to ensure that their markings meet policy standard. Analysis Language testing is an uncertain and approximate business at the best of times, even if, to the outsider, this may be camouflaged by its impressive, even daunting, technical (and technological) trappings, not to mention the authority of the institutions whose goal tests serve. Every test is vulnerable to good questions. (McNamara, 2000, p. 86) In analyzing the Academic version of the IELTS, I used frameworks developed by Wesche (1983) and Swain (1984) for test analysis. For each framework, a table has been developed that incorporates the corresponding component or principle. The following analysis discusses how Wesche’s components and Swain’s principles can be used to decamouflage the impressive and daunting nature of the International English Language Testing System. Wesche’s Framework In 1983 Wesche wrote, “all tests are samples of behaviour, intended to reflect whether the examinee possesses certain knowledge, or to predict whether he or she can perform certain acts. Tests generally consist of a number of items, each composed of stimulus material and a related task which requires a response on the part of the examinee. Responses are then scored according to certain criteria” (p. 43). Of particular salience are the key components: stimulus material, IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 11 task, response, and criteria. Fifteen years later, retouching upon the importance of Wesche’s components, Bailey (1998) addressed the four components in more elaborated accessible language. Stimulus material. Stimulus material, as defined by Bailey (1998) “refers to whatever linguistic or nonlinguistic information is presented to the learners to get them to demonstrate the skills of knowledge we want to asses” (p. 13). In the IELTS stimulus materials consist of a variety of question, text, and task types7. Tasked posed to the learner. The task posed to the learner refers to “that which must be done by a test taker to demonstrate his skill and/or knowledge, thereby successfully completing a test item or prompt” (Bailey, 1998, p. 248). The IELTS requires candidates to perform a wide range of reading skills, listening skills, writing skills, and speaking skills8. Learner’s response. The learner’s response is “the test-taker’s actions in response to the task that is posed by a prompt or an item; the observable manifestation that he or she can indeed do the mental task that has been set for him or her” (Bailey, 1998, p. 245). Across the four Modules, test takers are required to respond in various ways: speaking, writing, reading, and listening9. Scoring criteria. Candidates scores are reported on a nine point band score across each of the four Modules of the IELTS. Each band score10 is accompanied by a description which reflects the candidate’s respective skill proficiency according to performance11. See Appendix G for more detailed information on Stimulus Material within the table of Wesche’s Components. See Appendix G for more detailed information on Task posed to the learner within the table of Wesche’s Components. 9 See Appendix G for more detailed information on Learner’s Response within the table of Wesche’s Components. 10 See Appendix E for complete band score description. 11 See Appendix G for more detailed information on Scoring Criteria within the table of Wesche’s Components. 7 8 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 12 Swain’s Framework According to Swain (1984), there are four general principles relevant “when faced with the practical problems of developing a communicative test of speaking and writing that could be administered on a large scale, and that could be sensitive to a wide range of proficiency levels” (p. 188). As such, Swain’s four principles that test developers need to consider when designing a communicative test are: start from somewhere, concentrate on content, bias for best, and work for washback. Start from somewhere. This idea means that “assessment should be based on sound theoretical principles. It entails having a clear understanding of the construct we are trying to measure and designing our assessment procedures to match that understanding” (Bailey, 1998, p. 154). The IELTS purports to assess general English proficiency in all four modules. To an extent this is true, but after further investigation, the literary treatment of construct is concerning because it is seemingly insufficient12 (evidence that explicates construct in stakeholder literature is hard to come by). Concentrate on content. Concentrating on content means that “assessment devices should be appropriate in terms of the age, proficiency level, interests, and goals of the learners” (Bailey, 1998, p. 154). At face value, the IELTS is seemingly appropriate in terms of the preceding ideas, yet, after further review the appropriateness of content is easily problematized13. Bias for best. Bias for best means that, “tests should be designed so as to elicit the best possible performance from test-takers” (Bailey, 1998, p. 154). Similar to the preceding principles, although IELTS purports to “bias for the best” this may not be the case14. See Appendix H for Swain’s Principles elaborated per test module. Each cell presents what the IELTS purports to do (marked by +), and or a concern, criticism, or recommendation (marked by -). 13 See Appendix H for Swain’s Principles: Concentrate on content. 14 See Appendix H for Swain’s Principles: Bias for best. 12 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 13 Work for washback. Swain’s last principle, work for washback, refers to how a test influences, language instruction, and language learning. In Green’s (2007) words, washback is “the effect of testing on teaching and learning” (p. 76). Accordingly, there are two different argument strands evident in applied linguistics literature that advocates either negative or positive washback15. Reliability and Validity Wesche and Swain’s frameworks16 are also useful in the discussion of the IELTS reliability and validity. Test reliability is generally defined as “the extent to which the results can be considered consistent or stable” (Brown, 2005, p. 175). In terms of the overall reliability and Standard Error of Measurement (SEM) of the IELTS, reliability is quite high. Yet, high reliability is inherently meaningless: “a test might be highly reliable, in the sense of producing replicable measures, but completely irrelevant in terms of its content or predictive utility” (UCLES, 2001, p. 15). Based on the data presented in the 2001 Guidelines for Testing and Admissions Personnel, the Overall Reliability of the Academic module is reported at 0.94 and the SEM at 0.36. (SEM should be interpreted according to final bandscore). What this indicates is that, “for the Academic module, there is an approximately 68% probability that a candidates result is accurate to within .36 of a band, and a 95% probability that it is within .72 of a band” (UCLES, 2001, p. 16) In terms of validity, IELTS’ own research carefully considers construct, content, and criterion-related validity. As far as construct validity is concerned, ongoing research is undertaken “to explore the processes and identify the strategies which underlie the performance of candidates on IELTS tests, and which are specific to the constructs being tests by IELTS” 15 16 See Appendix H for arguments pertaining to negative and positive washback in each of the IELTS modules. See Appendix H for arguments pertaining to validity and test construct according to Swain’s Principles IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 14 (UCLES, 2001, p. 13). Looking at content validity, IELTS purports to attach great importance to selecting test content that “reflects an international dimension” (UCLES, 2001, p. 13). Additionally, IELTS recognizes that “positive relationships found between language proficiency measures and academic achievement tends to be relatively weak” (UCLES, 2001, p. 13). Therefore, IELTS continuously conducts criterion-related validity research in attempt to “demonstrate that test scores are systematically related to an outcome criterion or criteria” (UCLES, 2001, p. 13). Conclusion Reviewing the Academic Modules of the IELTS has been an informative process, especially when considering the impact of a high-stakes communicative test in terms of design and overall value. What has become clear, is that from reviewing a test of this nature, Pandora ’s Box has indeed been opened, in turn revealing the daunting nature of test development, test analysis, and the testing industry. As well, this review revealed that two parallel argument strands exist in literature pertaining to the IELTS. With this in mind, both arguments endorsing the IELTS, and arguments which criticize the IELTS, are equally valuable. In consideration of Swain and Wesche’s frameworks, this review process has been particularly interesting as it has shed light on how innumerable interrelated variables must be considered when designing and using such high-stakes assessment tools – for test creators, for test takers, and professional educators alike. IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 15 References Aryadoust, V. (2012). Differential Item Functioning in While-Listening Performance Tests: The Case of the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) Listening Module. The Intl. Journal of Listening, 26, 40-60. Bailey, K. M. (1998). Learning about language assessment: Dilemmas, decisions and directions. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle. Brown, J. D. (2005). Testing in language programs: A comprehensive guide to English language assessment (New ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J: Prentice Hall Regents. Carey, M & Mannell, R. (2010). Does a rater’s familiarity with a candidate’s pronunciation affect the rating in oral proficiency interviews?. Language Testing, 28(2), 201-219. Coffin, C. (2004). Arguing about how the world is or how the world should be: the role of argument in IELTS tests. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 3, 229-246. Green, A. (2007). Washback to learning outcomes: a comparative study of IELTS preparation and university pre-sessional language courses. Assessment in Education, 14, 75-97. Hall, G. (2010). International English language testing: a critical response. ELT Journal, 64(3), 321-326) IELTS: International English Language Testing System. (2013a). IELTS Test Takers FAQs, Retrieved October 3, 2013 from http://www.ielts.org/test_takers_information/test_takers_faqs.aspx IELTS: International English Language Testing System. (2013b). IELTS Researchers – Band descriptors, reporting, and interpretation, Retrieved October 3, 2013 from http://www.ielts.org/researchers/score_processing_and_reporting.aspx IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 16 IELTS: International English Language Testing System. (2013). IELTS Institutions, Retrieved October 3, 2013 from http://www.ielts.org/institutions.aspx IELTS: International English Language Testing System. (2013). IELTS Institutions – Security procedures, Retrieved October 3, 2013 from http://www.ielts.org/institutions/security_and_integrity/security_procedures.aspx IELTS: International English Language Testing System. (2013e). Institutions – Band scores, Retrieved October 3, 2013 from http://www.ielts.org/institutions/test_format_and_results/ielts_band_scores.aspx IELTS: International English Language Testing System. (2013). IELTS Test Taker Information – Test Sample, Retrieved October 3, 2013 from http://www.ielts.org/test_takers_information/test_sample.aspx McNamara, T. (2000). Language Testing (Oxford Introductions to Language Study Series) Oxford: Oxford University Press. Swain, M. (1984). Large-scale communicative language testing. In S. J. Savignon, & M. S. Berns (Eds.), Initiatives in communicative language teaching. Reading, MA: AddisonWesley. University of Cambridge Local Examination Syndicate. (2001). Introduction to IETLS: Guidelines for testing and admissions personnel. Cambridge, UK: UCLES. Uysal, H. (2009). A critical review of the IETLS writing test. ELT Journal, 64/3, 314-320. Wallace, C. (1997). IELTS: global implication of curriculum and materials design. ELT Journal, 51/4, 370-373. Weir, C., Hawkey, R., Green, A., Unaldi, A., Devi, S. (2009). The relationship between the academic reading construct as measured by IELTS and the reading experiences of student IELTS: A TEST REVIEW in their first year of study at a British university. IELTS Research Reports, Vol. 9. Retrieved October 1, 2013 from: http://www.ielts.org/PDF/Vol9_Report3.pdf Wesche, M. B. (1983). Communicative testing in a second language. The Modern Language Journal, 67, 41-55. 17 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 18 Appendix A: Sample Listening Materials IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 19 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 20 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 21 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 22 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 23 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 24 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 25 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 26 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 27 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 28 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 29 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 30 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 31 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 32 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 33 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 34 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 35 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 36 Appendix B: Sample Reading Materials IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 37 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 38 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 39 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 40 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 41 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 42 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 43 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 44 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 45 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 46 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 47 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 48 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 49 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 50 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 51 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 52 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 53 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 54 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 55 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 56 Appendix C: Sample Writing Materials IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 57 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 58 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 59 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 60 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 61 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 62 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 63 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 64 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 65 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 66 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 67 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 68 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 69 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 70 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 71 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 72 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 73 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 74 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 75 Appendix D: Sample Speaking Materials IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 76 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 77 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 78 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 79 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 80 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 81 Appendix E: Bandscore Descriptors Band 9: Expert user: has fully operational command of the language: appropriate, accurate and fluent with complete understanding. Band 8: Very good user: has fully operational command of the language with only occasional unsystematic inaccuracies and inappropriacies. Misunderstandings may occur in unfamiliar situations. Handles complex detailed argumentation well. Band 7: Good user: has operational command of the language, though with occasional inaccuracies, inappropriacies and misunderstandings in some situations. Generally handles complex language well and understands detailed reasoning. Band 6: Competent user: has generally effective command of the language despite some inaccuracies, inappropriacies and misunderstandings. Can use and understand fairly complex language, particularly in familiar situations. Band 5: Modest user: has partial command of the language, coping with overall meaning in most situations, though is likely to make many mistakes. Should be able to handle basic communication in own field. Band 4: Limited user: basic competence is limited to familiar situations. Has frequent problems in understanding and expression. Is not able to use complex language. Band 3: Extremely limited user: conveys and understands only general meaning in very familiar situations. Frequent breakdowns in communication occur. Band 2: Intermittent user: no real communication is possible except for the most basic information using isolated words or short formulae in familiar situations and to meet immediate needs. Has great difficulty understanding spoken and written English. Band 1: Non-user: essentially has no ability to use the language beyond possibly a few isolated words. Band 0: Did not attempt the test: No assessable information provided. IELTS: International English Language Testing System. (2013e). Institutions – Band scores, Retrieved October 3, 2013 from http://www.ielts.org/institutions/test_format_and_results/ielts_band_scores.aspx IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 82 Appendix F: Band score associated with raw score Listening and reading “IELTS Listening and Reading papers contain 40 items and each correct item is awarded one mark; the maximum raw score a candidate can achieve on a paper is 40. Band scores ranging from Band 1 to Band 9 are awarded to candidates on the basis of their raw scores. Although all IELTS test materials are pretested and trialed before being released as live tests, there are inevitably minor differences in the difficulty level across tests. In order to equate different test versions, the band score boundaries are set so that all candidates’ results relate to the same scale of achievement. This means, for example, that the Band 6 boundary may be set at a slightly different raw score across versions. The tables below indicate the mean raw scores achieved by candidates at various levels in each of the Listening, Academic Reading and General Training Reading tests and provide an indication of the number of marks required to achieve a particular band score.” http://www.ielts.org/researchers/score_processing_and_reporting.aspx IELTS: A TEST REVIEW Appendix G: Table - Wesche’s Framework 83 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 84 Appendix H: Table - Swain’s IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 85 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 86 Appendix I: General information IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 87 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 88 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 89 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 90 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 91 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 92 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 93 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 94 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 95 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 96 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 97 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 98 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 99 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 100 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 101 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 102 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 103 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 104 IELTS: A TEST REVIEW 105