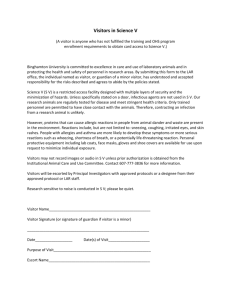

Document

advertisement

Plato’s Academy, a

mosaic in the Museo

Nazionale, Naples,

(Photo: Giraudon)

The Statesman, (257A-291C, pp. 294 -335) .

Philosophy 190: Plato

Fall, 2014

Prof. Peter Hadreas

Course website:

http://www.sjsu.edu/people/peter.hadreas/cour

ses/Plato

Topic of the Statesman:

What is the art of

statesmanship

and how might it be applied

well

Was Napoleon a good statesman?

A good political leader?

Is Barack Obama a good statesman?

A good political leader?

Who Is the Eleatic Visitor’s Interlocutor:

The “Younger” Socrates

The Socrates of Plato’s early and middle dialogues,

as in the Sophist, is silent in the Statesman except for

a few opening remarks. The “younger” Socrates, of

the Statesman, is mentioned once in the Theaetetus

(147D1) as studying mathematics with Theodorus

and Theaetetus. He was likely an early member of

Plato’s Academy. He is mentioned once in Plato’s

Tenth Letter (358E). Aristotle also mentions him once

in the Metaphysics (Meta, B 1036b25) in a way that

suggests he belonged to a group in the Academy that

Aristotle reproaches for their ‘pan-mathematicism.’

Result of Division (Diaeresis) I (p. 308, 267B-C)

VISITOR: Well then; of theoretical knowledge, we had at the

beginning a directive part; and of this, the section we wanted

was by analogy said to be ‘self-directing.’ Then again, rearing

of living creatures, not the smallest classes of self-directing-self

knowledge, was split off from it; then a herd-rearing form

from rearing of living creatures, and from that in turn,

rearing of what goes on foot; and from that, as the relevant

part, was cut off the expertise of rearing the hornless sort. Of

this in turn the part must be woven together as not less than

triple, if one want to bring it together in a single name, calling

it expert knowledge of rearing of non-interbreeding creatures.

The segment from this, a part relating to a two-footed flock,

concerned with rearing of human beings, still left on it own –

this very part is now what we were looking for, the same thing

we call both kingly and statesman like.

End of Diaeresis I (p. 308, 267B-C) Is a Joke 1

The last divisions of the “longer way” of the first Diaeresis

265E-266C hardly can be meant seriously The Stranger says

that the young Socrates and Theaetetus need to divide up –

literally ‘tear open’ -- the nurturing of hornless land-dwelling

herd animals. (There’s a problem with dogs because they travel

in packs when wild, but singly or severally with human beings

when tame.) But especially funny is the comparison of fourfooted animals to the square root of four and two-footed

animals to the square root of two. As Rosen points out this is a

Platonic joke. (Two-footed land animals are ‘irrational’ like √2).

And especially a joke or joke-like is the Visitor calling human

beings “the noblest and laziest race” (266B10-C6) playing on

the word for ‘pig.’

1. Indebted to Stanley Rosen for these observations. See Rosen, Stanley, Plato’s

Statesman: The Web of Politics, (South Bend, IN: St, Augustine’s Press, 2009), pp.

34-35.

End of (Diaeresis) I (p. 308, 267B-C) Is a Joke 1

“The shorter way” (266D-267A) – the last revision in the first

Diaeresis -- also seems to be ironical. The shorter way takes for

granted that human beings are the only two-footed featherless

animals, drops the main condition of the political art as a tender

of human beings and inserts that the political leader holds the

reins of the city. This suggests a comparison between human

beings and horses. So we end up with the conclusion that the

royal and political art is the pastoral science of unmixed

breeders, a herding of two-footed animals.

1. Again adapted from Rosen, Stanley, Plato’s Statesman: The Web of Politics, (South

Bend, IN: St, Augustine’s Press, 2009), pp. 34-35.

The Statesman Diaeresis I is an Example of the

Misapplication the Method of Division in the

Determination of a Type .1

The progress of the first application definition by Division,

Diaeresis I, in the Statesman methodically demonstrates the

misapplication of this manner of analysis. Each forward

division step is revealed to be a step backward; admitted to be a

failure; and, the correction of errors are made through further

errors. The goal of the Method of Division is to uncover a

natural and conceptual order. But this sequence of division

relies on a freakish system of distinctions. Commentators find

fundamental Socratic irony

The Statesman Diaeresis I is an Example of the

Misapplication the Method of Division in the

Determination of a Type1

[from previous slide]

in the Early and Middle Plato Dialogues with little exception

have been able to find irony in the Statesman. Few

commentators allow Plato the same rhetorical complexity in this

later dialogue. One of the few who reads the Statesman giving

Plato the license to irony in the Statesman is Rosen. Rosen

writes about Diaeresis I: “Philosophy is transformed into

technology and the doctrine of Ideas into ideology. Platonism is

then indistinguishable from the late-modern version of the

Enlightenment, according to which humans make themselves.”

1. Rosen, Stanley, Plato’s Statesman: The Web of Politics, (South Bend, IN:

St, Augustine’s Press, 2009), p. 36.

The Incompleteness of Diaeresis I: the Introduction of

the Myth of a Forward and Backward Moving Cosmos

Immediately following his summary of Diaeresis I, the Visitor

says that the previous result of the Method of Division has not

been entirely successful (267C-D). In the case of the non-human

herds there seems to be one art – and type of person – capable

of caring for them. But in the case of human beings there are

numerous types of professionals and producers who nurture

people along with the statesman. There are for example,

merchants, farmers, grain producers, gymnasts and physicians

(2676-268A). In terms of Plato’s previous dialogues and his

later dialogues such as the Timaeus and the Philebus we should

also note that Diaeresis I of the Statesman is directed towards

the human animal. There is an avoidance of any knowledge or

technē that might be concerned with ‘the best’ or the Good. The

dialogue will finally arrive at the ‘Socratic ‘ conclusion. But the

initial investigation of the Visitor seems to methodically avoid it.

The Myth of the Statesman:

A Forward and

Backward-Moving Cosmos

Myth of a Forward and

Backward Moving Cosmos - I

Introduction

(268E-269C)

The Visitor refers to tales recounted by ancients. He

says many actually took place and will occur again.

(The Statesman myth bears comparison to

Nietzsche’s Eternal Recurrence of the Same.) The

Visitor mentions the account of the heavenly sign

marked upon the strife between Atreus and

Thyestes. The legend that the Visitor refers to is

about strife between two brothers Atreus and

Thyestes who fight over who should be king. Zeus

settles the dispute in preference of Atreus.

Myth of a Forward and

Backward Moving Cosmos –I

Introduction

(268E-269C) [continued]

Zeus then changes the course of the sun and the

Pleiades as a sign of his decision. The Visitor in the

Statesman revises the legend. Instead of changing

the motion of the sun and the Pleiades, The Visitor

has Zeus changing the motion of the entire cosmos,

a motion which perpetually recurs. Hence forward

there is the epoch of the motion of the cosmos as we

know it, followed and preceded by its reversal. This

recurs perpetually. We’ll call the first the forward

epoch and the second the reverse epoch.

Ruins of Mycenae. Thought to be Atreus’ treasure or

perhaps Agamemnon’s tomb.

Myth of a Forward and

Backward Moving Cosmos - II

Description of Cosmic Motion (269C-270B)

The Visitor refers to the god who guides all. This would suggest

a Demiurge. Neither Zeus the ‘Forward Epoch’ god nor

Cronus the ‘Reverse Epoch’ god will qualify since they operate

within their specific epochs. Some overriding Demiurge guides

the cosmos which is described as possessing a body and being

alive. The Visitor describes the Reverse Epoch in which things

become younger. Humans and animals who are previously dead

are resurrected from the earth at the point of their death and

then they become younger entering into middle age, youth, and

infancy until they become seeds and are sewn in the earth. The

rejuvenation is described as a process of unraveling, so mental

and perceptual processes unravel as well. To the extent there is

any knowledge it is subject to a process of forgetting.

Myth of a Forward and

Backward Moving Cosmos - III

Consequences of Reverse Cosmic Motion (270B – 271C)

Most animals and especially humans cannot sustain the process

of the reversal of becoming younger. The Reverse Epoch begins

when the cosmos has undergone the final period of the

Forward Epoch which was the last stages of destruction an

decay. The cosmic reversal is a kind of purgation – perhaps an

ancient version of modern theories of revolution which

maintain that current civilization must be destroyed – or

largely destroyed -- before a fair and just society may be

inaugurated. Rosen observes that during this period the

Platonic Ideas or Forms must remain particularly in the

background because nothing is keeping “its look,” its eidos or

form since everything in becoming younger is changing and

unravelling.1

1. Quoted from Rosen, Stanley, Plato’s Statesman: The Web of Politics,

(South Bend, IN: St, Augustine’s Press, 2009), p. 49.

Myth of a Forward and

Backward Moving Cosmos - IV

The Reverse Epoch is Ruled by Cronus (271C – 272B)

Hesiod: Works and Days (109ff.):

“’The deathless ones who dwell upon Olympus first made the

golden race of articulate human beings. These belong to the time

of Kronos, when he was king in heaven. They lived like gods with

a careless spirit, far from pains and misery. Nor did miserable

old age approach them.’ For these residents of the golden age,

death was like a falling asleep. They did no work; all goods were

theirs by nature’s bounty. This race was followed by the silver

race who enjoyed a childhood of one hundred years, followed by

a brief adulthood marked by by crime and an absence of divine

worship. They were destroyed by Zeus. The third race, produced

by Zeus, is that of bronze and consists of warriors. The heroes

make up the fourth race, and we ourselves are the fifth race who

inhabit the age of iron.” 1. As summarized by Rosen, Stanley, Plato’s

Statesman: The Web of Politics, (South Bend, IN: St, Augustine’s Press, 2009),

Homeric

Kings

were

likened to

shepherds

The "Agamemnon" Mask, Gold, from Tomb V at Mycenae,

Sixteenth century BC, National Archeological Museum, Athens.

Agamemnon is referred to repeatedly in the Iliad as “shepherd

of the people.” See Iliad, Book IV, 295, 413.

Cronus & Rhea, Athenian red-figure pelike, circa 5th B.C., M

The Era of Cronos (Statesman 268d–275c)

Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Golden Age

Joachim Wtewael, The Golden Age

Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Silver Age

Virgil Solus, (1514 - 1562)

The Iron Age

Myth of a Forward and

Backward Moving Cosmos - IV

The Reverse Epoch is Ruled by Cronus (271C – 272B)

The Reverse Epoch, which is ruled by Cronus in Plato’s myth,

has similarities to the Golden Age described by Hesiod, but there

are many differences. Cronus is the shepherd of all humans. The

reference to Cronus as a shepherd is very likely meant to make

puerile conceiving the art of statesmanship as a kind of

shepherding. Animals and humans in the Reverse Epoch and

humans are blissful but also increasingly ignorant. Cronus

shepherds humans. Every herd of animals is shepherded by a

daimon. There is no meat eating, no war, no sedition. People eat

fruit and of course continue to become younger. They have “no

political constitutions, nor acquired wives and children, for all of

them came back to life from the earth, remembering nothing of

the past.” (pp. 314-5, 271E-272A)

Myth of a Forward and

Backward Moving Cosmos - V

Speculation About The Age of Cronus (272B– 272D)

In this short section, the Visitor says that “if the nurslings of

Cronus” have speech and use it to gather wisdom there lives will

be “far more fortunate than those who live now.” But “if they

spend their time gorging themselves with food and drink and

exchanging stories with each other and and with the animals of

the sort even now are told about them, this too, if I may reveal

how it seems to me, is a matter that is easily judged.” (p. 314,

272D). This would seem to be another Platonic irony, since this

myth is can be thought of as an ‘exchanging of stories.’ Further

Plato is ironically portraying the condition of what it would like

to be utterly controlled by some superior being, even if the being

is benevolent. It’s a Garden of Eden without the Tree of

Knowledge and in Plato’s construct without Eros.

Myth of a Forward and

Backward Moving Cosmos - VI

Rotation from Reverse Epoch to Forward Epoch (272D– 273E)

We recall the cosmos has its own life and unity. Once the

shepherd-like rule of Cronus had brought the earthborn humans

to a fully blissful and peaceful if vegetable-like state “ . . . The

steersman of the universe, let go, -- as it were – of the bar of the

steering oars and retired to his observation post; and as the for

the cosmos, its allotted and innate desire turned it back again in

its opposite direction.” (pp. 314-5; 272E) This produced a great

tremor which in turn brings about another destruction of all sorts

of living things, but in time “. . . It set itself in order, into the

accustomed course that belongs to it, itself taking charge of and

mastering both the things within it and itself.” But the

accustomed order in the long run finally returns again to selfdestruction and the whole process of reversing time and

rejuvenation recycles again, “… rendering it immortal and

ageless.” (p. 315, 273E).

Myth of a Forward and

Backward Moving Cosmos - VII

Point of the Myth (273E-274E)

“We are now at the point that our account has all along been

designed to reach. . . . Everything that has helped to establish

human life has come from these things, once care from the gods,

as has just been said, ceased to be available to human beings, and

they had to live their lives through human resources and take

care for themselves, just like the cosmos as a whole, which we

imitate and follow for all time, now living and growing in this

way, now in the way we did then. As for the matter of our story,

let it now be ended, and we shall put it to use in order to see how

great our mistake was when we gave our account of the expert in

kingship and statesmanship in our preceding argument.”

What the Main Errors of Diaeresis I?

The Younger Socrates asks and the Visitor Responds

(274E-275A, p. 316)

YOUNG SOCRATES: So how do you say we made a mistake and how great

was it?

VISITOR: In one way it was lesser, in another way it was very high-minded,

and much greater and more extensive than the other case.

YOUNG SOCRATES: How so?

VISITOR: In that when asked for a king and statesman from the period of the

present mode of rotation and generation we replied with a shepherd from the

opposite period, who cared for the herd that existed then, and at that a god

instead of a mortal – in that way we went very astray. But in that we revealed

him as ruling over the whole city together, without specifying what manner his

does so, in this way, by contrast, what we said was true but incomplete and

unclear, which is why our mistake was lesser than in the respect just

mentioned.”

Preliminary Pass at a Definition of the Statesman

276D-277A, pp. 318-319

VISITOR: First of all, as we are saying we should have altered

the name, aligning it more with caring for things than with

rearing, and then we should have cut this; for it will still offer

cuts of no small size.

YOUNG SOCRATES: When would they be?

VISITOR: I imagine, where we would have divided off the

divine herdsman, on o0ne side, and the human carer on the

other.

YOUNG SOCRATES: Correct.

VISITOR: But again we ought to have cut into two the art of

the carer resulting from this appointment.

YOUNG SOCRATES: By using what distinction?

VISITOR: That between the enforced and the voluntary.

YOUNG SOCRATES: Why so?

Preliminary Pass at a Definition of the Statesman

276D-277A, pp. 318-319 [continued]

VISITOR: I think we made a mistake before in this way too, by behaving

more simple-mindedly than we should have. We put king and tyrant into

the same category, when both they themselves and the manner of their rule

are very unlike one another.

YOUNG SOCRATES: True.

VISITOR: But now we should set things to rights again, and, as I said,

should we divide the expertise of the human carer into two, by using the

categories of the enforced and the voluntary?

YOUNG SOCRATES: Absolutely

VISITOR: And should we perhaps call tyrannical the expertise that relates

to subjects who are forced, and the herd-keeping that is voluntary and

relates to willing two-footed living things that expertise which belongs to

statesmanship, displaying, in his turn, the person who has expertise and

cares for his subjects in this way as being genuine king and subject?

YOUNG SOCRATES: Yes, visitor, and it’s likely that in this way our

exposition concerning the statesman would reach its completion.

Filling out the Sketch

VISITOR: “ . . . We took upon ourselves an astonishing mass

of material in the story we told, so forcing ourselves to use a

greater part than was necessary; thus we have made our

exposition longer, and have in every way failed to apply a

finish to our story, and our account, just like a portrait, seems

adequate in its superficial outline, but not yet to have received

its proper clarity, as it were with paints and the mixing

together of colors. But it is not painting or any other sort of

manual craft, but speech and discourse, that constitute the

more fitting medium for exhibiting all living things, for those

who are able to follow; for the rest, it will be through manual

crafts.”1

1. It seems then somewhat arrogant of the Visitor proceeds

through the analogy of manual crafts, weaving and clothesmaking.

The Paradigm of Weaving in the Statesman

(279B, p. 321)

“VISITOR: So what model, involving the same activities

[pragmateia] as statesmanship, on a very small scale, could one

compare with it, and so discover in a satisfactory way what we

are looking for? By Zeus what do you think? If there isn’t

anything else at and, well, what about weaving? Do you want us

to choose that? Not all of it, if you agree, since perhaps the

weaving of cloth from wool will suffice; maybe it is part of it, if

we choose it, which would provide testimony if we want.

YOUNG SOCRATES: I’ve certainly no objection.

The Paradigm of Weaving in the Statesman

The Visitor does say (285E, p. 329):

“I certainly don’t suppose that anyone with any sense would

want to hunt down the definition of weaving for the sake of

weaving itself.”

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

How is Weaving like Statesmanship

(279B, p. 321)

The Visitor says they are both activities or ‘pragmateia’. This

word should be distinguished from knowledge: epistēmē or

gnōstikē. It means diligence in business or in a practice.

Pragmateia as ‘applied study’ is halfway between knowledge

and practice.1

Weaving like good politics provides protection against nature.

Clothes in general are to the body as the polis is to the citizen.

Statesmanship like weaving depends on other arts.

An analogy is drawn between the warp or hard threads and

the spirited or hard-souled citizens and between the woof and

soft threads and then gentle citizens. Various weaves are

various blends of the two types of character.

1. Thanks again to Rosen for this characterization of pragmateia. Rosen, Stanley,

Plato’s Statesman: The Web of Politics, (South Bend, IN: St, Augustine’s Press, 2009),

p. 101.

Raw wool that has been carded and made into ‘rolags’’

Woman spinning. Detail from an Ancient Greek attic

white-ground oinochoe, ca. 490 BC, from Locri, Italy.

British Museum, London..

‘Weft’ and ‘woof’ are Old English words for ‘woven.’

The Art of Measurement

Its Two Types and the Assessment of

Moral/Aesthetic/Political value

283B-287A, pp. 327-330

The Eleatic Visitor, considering whether he’s been going on too

long, takes up a discussion of two kinds of measurement.

(metrētikē). The first accords with the ordinary concept of

measurement. We measure “number, lengths, depths, breadths

and things in relation to what is opposed to them.” (284E, p. 328).

“what is opposed to them’ implies some standard which is not

being measure, but which is a criterion for the measuring, as a,

inch foot or a mile – millimeter, kilometer -- might be for length,

depth and breadth.

The Art of Measurement:

Its Two Types and the Assessment of

Moral/Aesthetic/Political value

283B-287A, pp. 327-330

[continued from previous slide]

But the second type of measurement is the distinction, with very

significant revision, that will become Aristotle’s notion of virtue

as a mean between an excess and a deficiency. The Visitor

introduces the notion by saying (283E, p. 326): “What about

this: shan’t we also say that there really is such a thing as what

exceeds in due measure [πρὸς τὸ μέτριον, pros to metrion]1, and

everything of that sort, in what we say or what we do? Isn’t it

just in respect that those of us who are bad and those of us who

are good most differ?

YOUNG SOCRATES: It seems so.

1. πρὸς τὸ μέτριον, pros to metrion which Rowe translates as ‘due measure’ is

literally translated as ‘toward the mean.’

The Art of Measurement

283B-287A, pp. 327-330

[continued from previous slide]

VISITOR: In that case we must lay it down that the great and the small exist

and are objects of judgment in these twin ways. It is not as we said just before,

that we must suppose them to exist only in relation to each other. But rather as

we have just now said, we should speak of their existing in one way in relation

to each other, and in another in relation to what is in due measure. Do we want

to know why?

YOUNG SOCRATES: Of course.

VISITOR: If someone will admit will admit the existence of the greater and

everything of the sort in relation to nothing other than the less,1 it will never be

in relation to what is in due measure – you agree?

YOUNG SOCRATES: Of course.

1. NOTE: The visitor apparently doesn’t have the vocabulary to speak of parameters

of measurement, such, meters, pounds, degrees of Centigrade, miles per hour, etc. , but

his meaning is clear enough: we measure something by a lesser part of it, a degree

Centigrade is an increment – lesser part – of heat, etc. But ‘due measure’ as in the

sweater or shoe is the right size is something quite different. And Plato’s goal is clearly

not to apply due measure to crafts but to find the due measure between an excess and

and a deficiency in the actions of a statesman.

The Art of Measurement

283B-287A, pp. 327-330

[continued from previous slide]

VISITOR: Well, with this account of things we shall destroy – shan’t we? –

both the various sorts of expertise themselves and their products, and in

particular we shall make the one we are looking for now, statesmanship,

disappear, and the one we said was weaving. For I imagine all sorts of

expertise guard against what is more and less than what is in due measure, not

as something which is not, but as something which is and is troublesome in

relation to what they do. It is by preserving measure in this way that they

produce all the good and fine things they produce.

YOUNG SOCRATES: Of course.

VISITOR: If, then, we make the art of statesmanship disappear, our search

after that for the knowledge of kingship will lack any way forward?

YOUNG SOCRATES: Very much so.

1. NOTE: Unlike Aristotle, Plato applies the mean, as the ‘due measure,’ not only to

the moral virtues but to acts of human production, to studied skills, to technai in

general.

The Art of Measurement

283B-287A, pp. 325-330

[continued from previous slide]

VISITOR: Is it the case then just as with the sophist we compelled what is not

into being as well as what is, when our argument escaped us down the route,

so now we must compel the more and less, in their turn, to become measurable

not only in relation to each other, but also in relation to the coming into being

of what is due measure? For if this has not been agreed, it is certainly not

possible for either the statesman or anyone else who possesses knowledge of

practical subjects to acquire an undisputed existence.

YOUNG SOCRATES: Then now too we much do as much as we can.

VISITOR: This task, Socrates, is even greater than the former one – and we

remember what the length of that was. Still, it’s very definitely fair to propose

the following hypothesis about the subject in question.

YOUNG SOCRATES: What’s that?

The Art of Measurement

283B-287A, pp. 325-330

[continued from previous slide]

VISITOR: That at some time we shall need what I referred to just now for

the sort of demonstration what would be commensurate with the precise

truth itself. But so far as concerns what is presently being shown, quite

adequately for our immediate purpose, the argument we are using seems

to me to come to our aid in a magnificent fashion. Namely, we should

surely suppose that it is similarly the case that all the various sorts of

expertise exist, and at the same time that greater and less are measured

not only in relation to each other but also in relation to the coming into

being of what is in due measure. For if the latter is the case, then so is the

former, and also if it is the case that the sorts of expertise exist, the other is

the case too. But if one or the other is not the case, then neither of them

will ever be.

YOUNG SOCRATES: This much is right, but what’s the next move after

this?

The Art of Measurement

283B-287A, pp. 325-330

[continued from previous slide]

VISITOR: It’s clear that we should divide the art of

measurement, cutting it in two in just the way we said,

positing as one part of it, all those sorts of expertise that

measure number, lengths, depths, breadths and speeds of

things in relation what is opposed to them, and as the other,

all those that measure in relation to what is due measure,

what is fitting, the right moment, what is as it ought to be –

everything that removes itself from the extremes to the

middle.

YOUNG SOCRATES: Each of the two sections you refer to is

indeed a large one, and very different from the other.

Cut to Final Definition of the Statesman

(304A, p. 248-9) “VISITOR: Well, is seems that in the same

way we have now separated off those things that are different

from the expert knowledge of statesmanship, and those that

are alien and hostile to it, and there remain those that are

precious and related to it. Among those, I think, are

generalship, the art of the judge and that part of rhetoric

which in partnership with kingship persuades people of what

is just and so helps in steering through the business of cities. .

. .”

[continued]

Cut to Final Definition of the Statesman

continued from previous slide]

(305A, p. 351) “VISITOR: If then one looks at all the sorts of

expert knowledge that have been discussed, it must be

observed that none of them has been declared to be

statesmanship. For which is really kingship must not itself

perform practical tasks, but control them with the capacity to

perform them, because it knows when it is the right time to

begin and set in motion the most important things in cities,

and when it is the wrong time, and the others must do what

has been prescribed for them.”

Niccolò Machiavelli

{1469 –1527)

Niccolò Machiavelli

{1469 –1527)

Niccolò Machiavelli and the problem

of the traditional moral virtues if

practiced by a political leader.

The Prince

From Chapter XV

“Therefore, putting on one side imaginary things

concerning a prince, and discussing those which

are real, I say that all men when they are spoken

of, and chiefly princes for being more highly

placed, are remarkable for some of those qualities

which bring them either blame or praise;

and thus it is that one is reputed liberal, another miserly, . .

one is reputed generous, one rapacious; one cruel, one

compassionate; one faithless, another faithful; one effeminate

and cowardly, another bold and brave; one affable, another

haughty; one lascivious, another chaste; one sincere, another

cunning; one hard, another easy; one grave, another frivolous;

one religious, another unbelieving, and the like.”

The Prince

From Chapter XV [continued]

“And I know that every one will confess that it

would be most praiseworthy in a prince to exhibit

all the above qualities that are considered good;

but because they can neither be entirely possessed

nor observed, for human conditions do not permit

it, it is necessary for him to be sufficiently prudent

that he may know how to avoid the reproach of

those vices which would lose him his state; and

also to keep himself, if it be possible, from those

which would not lose him it; but this not being

possible, he may with less hesitation abandon

himself to them.”

The Prince

From Chapter XVI — Concerning Liberality And

Meanness – selection

“Therefore, any one wishing to maintain among

men the name of liberal is obliged to avoid no

attribute of magnificence; so that a prince thus

inclined will consume in such acts all his property,

and will be compelled in the end if he wish to

maintain the name of liberal, to unduly weigh down his people,

and tax them, and do everything he can to get money. This will

soon make him odious to his subjects, and becoming poor he

will be little valued by any one; thus, with his liberality, having

offended many and rewarded few, he is affected by the very first

trouble and imperilled by whatever may be the first danger;

recognizing this himself, and wishing to draw back from it, he

runs at once into the reproach of being miserly.”

The Prince

From Chapter XVI — Concerning Liberality And

Meanness – selection [continued]

“Either you are a prince in fact, or in a way to

become one. In the first case this liberality is

dangerous, in the second it is very necessary to be

considered liberal; and Caesar was one of those

who wished to become pre-eminent in Rome;

but if he had survived after becoming so, and had not

moderated his expenses, he would have destroyed his

government. . . . And there is nothing wastes so rapidly as

liberality, for even whilst you exercise it you lose the power to

do so, and so become either poor or despised, or else, in

avoiding poverty, rapacious and hated. And a prince should

guard himself, above all things, against being despised and

hated; and liberality leads you to both. “

The Prince

Chapter XVII — Concerning Cruelty And Clemency,

And Whether It Is Better To Be Loved Than Feared -selections

“Therefore a prince, so long as he keeps his subjects

united and loyal, ought not to mind the

reproach of cruelty; because with a few examples he will be more merciful

than those who, through too much mercy, allow disorders to arise, from

which follow murders or robberies; for these are wont to injure the whole

people, whilst those executions which originate with a prince offend the

individual only. . . . And of all princes, it is impossible for the new prince1

to avoid the imputation of cruelty, owing to new states being full of

dangers.” [Emphasis added]

1. Many commentators have argued that with The Prince Machiavelli

addresses a state in a highly weakened an corrupt state that needs

extraordinary methods to restore itself. Consider: "In fact, when there is

combined under the same constitution a prince, a nobility, and the power

of the people, then these three powers will watch and keep each other

reciprocally in check." Book I, Chapter II, Discourses on Livy.

The Prince

Chapter XVII — Concerning Cruelty And Clemency,

And Whether It Is Better To Be Loved Than Feared -selections

“Upon this a question arises: whether it be

better to be loved than feared or feared

loved? It may be answered that one should wish to be both,

but, because it is difficult to unite them in one person, it is

much safer to be feared than loved, when, of the two, either

must be dispensed with. Because this is to be asserted in

general of men, that they are ungrateful, fickle, false,

cowardly, covetous, and as long as you succeed they are yours

entirely; they will offer you their blood, property, life, and

children, as is said above, when the need is far distant; but

when it approaches they turn against you.

The Prince

Chapter XVII — Concerning Cruelty And Clemency,

And Whether It Is Better To Be Loved Than Feared -selections

And that prince who, relying entirely on their promises, has

neglected other precautions, is ruined; because friendships

that are obtained by payments, and not by greatness or

nobility of mind, may indeed be earned, but they are not

secured, and in time of need cannot be relied upon; and men

have less scruple in offending one who is beloved than one who

is feared, for love is preserved by the link of obligation which,

owing to the baseness of men, is broken at every opportunity

for their advantage; but fear preserves you by a dread of

punishment which never fails.

The Prince

Chapter XVII — Concerning Cruelty And Clemency,

And Whether It Is Better To Be Loved Than Feared -selections

Nevertheless a prince ought to inspire fear in such a way that,

if he does not win love, he avoids hatred; because he can

endure very well being feared whilst he is not hated, which will

always be as long as he abstains from the property of his

citizens and subjects and from their women. But when it is

necessary for him to proceed against the life of someone, he

must do it on proper justification and for manifest cause, but

above all things he must keep his hands off the property of

others, because men more quickly forget the death of their

father than the loss of their patrimony.

The Prince

Chapter XVII — Concerning Cruelty And Clemency,

And Whether It Is Better To Be Loved Than Feared -selections

Besides, pretexts for taking away the property are never

wanting; for he who has once begun to live by robbery will

always find pretexts for seizing what belongs to others; but

reasons for taking life, on the contrary, are more difficult to

find and sooner lapse. But when a prince is with his army, and

has under control a multitude of soldiers, then it is quite

necessary for him to disregard the reputation of cruelty, for

without it he would never hold his army united or disposed to

its duties.

The Prince

Chapter XVII — Concerning Cruelty And Clemency,

And Whether It Is Better To Be Loved Than Feared -selections

....

“Returning to the question of being feared or loved, I come to

the conclusion that, men loving according to their own will

and fearing according to that of the prince, a wise prince

should establish himself on that which is in his own control

and not in that of others; he must endeavour only to avoid

hatred, as is noted.”

The Prince

Chapter XVIII(*) — Concerning The Way In Which

Princes Should Keep Faith

(*) "The present chapter has given greater offence than any

other portion of Machiavelli's writings." Burd, "Il

Principe," p. 297.

. . . Therefore a wise lord cannot, nor ought he to, keep faith

when such observance may be turned against him, and when

the reasons that caused him to pledge it exist no longer. If men

were entirely good this precept would not hold, but because

they are bad, and will not keep faith with you, you too are not

bound to observe it with them. Nor will there ever be wanting

to a prince legitimate reasons to excuse this non-observance.

Of this endless modern examples could be given, showing how

many treaties and engagements have been made void and of

no effect through the faithlessness of princes; and he who has

known best how to employ the fox has succeeded best.

The Prince

Chapter XVIII(*) — Concerning The Way In Which

Princes Should Keep Faith

(*) "The present chapter has given greater offence than any

other portion of Machiavelli's writings." Burd, "Il

Principe," p. 297.

. . . But it is necessary to know well how to disguise this

characteristic, and to be a great pretender and dissembler;

and men are so simple, and so subject to present necessities,

that he who seeks to deceive will always find someone who will

allow himself to be deceived.

Alexander never did what he said,

Cesare never said what he did.

(Italian Proverb.)

The Prince

Chapter XVIII(*) — Concerning The Way In Which

Princes Should Keep Faith

(*) "The present chapter has given greater offence than any

other portion of Machiavelli's writings." Burd, "Il

Principe," p. 297.

Therefore it is unnecessary for a prince to have all the good

qualities I have enumerated, but it is very necessary to appear

to have them. And I shall dare to say this also, that to have

them and always to observe them is injurious, and that to

appear to have them is useful; to appear merciful, faithful,

humane, religious, upright, and to be so, but with a mind so

framed that should you require not to be so, you may be able

and know how to change to the opposite.

The Prince

Chapter XVIII(*) — Concerning The Way In Which

Princes Should Keep Faith

(*) "The present chapter has given greater offence than any

other portion of Machiavelli's writings." Burd, "Il

Principe," p. 297.

“And you have to understand this, that a prince, especially a

new one, cannot observe all those things for which men are

esteemed, being often forced, in order to maintain the state, to

act contrary to fidelity,(*) friendship, humanity, and religion.

Therefore it is necessary for him to have a mind ready to turn

itself accordingly as the winds and variations of fortune force

it, yet, as I have said above, not to diverge from the good if he

can avoid doing so, but, if compelled, then to know how to set

about it.”

The Prince

Chapter XIX — That One Should Avoid Being Despised

And Hated

“Now, concerning the characteristics of which mention is

made above, I have spoken of the more important ones, the

others I wish to discuss briefly under this generality, that the

prince must consider, as has been in part said before, how to

avoid those things which will make him hated or contemptible;

and as often as he shall have succeeded he will have fulfilled

his part, and he need not fear any danger in other

reproaches.”

The Prince

Chapter XIX — That One Should Avoid Being Despised

And Hated

“It makes him hated above all things, as I have said, to be

rapacious, and to be a violator of the property and women of

his subjects, from both of which he must abstain. And when

neither their property nor their honor is touched, the majority

of men live content, and he has only to contend with the

ambition of a few, whom he can curb with ease in many ways.”

The Prince

Chapter XIX — That One Should Avoid Being Despised

And Hated

“It makes him contemptible to be considered fickle, frivolous,

effeminate, mean-spirited, irresolute, from all of which a

prince should guard himself as from a rock; and he should

endeavour to show in his actions greatness, courage, gravity,

and fortitude; and in his private dealings with his subjects let

him show that his judgments are irrevocable, and maintain

himself in such reputation that no one can hope either to

deceive him or to get round him.”

Slide #4; portrait of

Napoleon,http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#mediaviewer/File:JacquesLouis_David_-_The_Emperor_Napoleon_in_His_Study_at_the_Tuileries__Google_Art_Project.jpg

Slide #5, photograph of Barack Obama:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barack_Obama#mediaviewer/File:President_Barack_

Obama.jpg

Slide #7: schema of first two diaereses in Plato’s Statesman:

http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/data/13030/gn/ft2199n7gn/figures/ft219

9n7gn_00009.gif

Slide #16: photograph of ruins of Mycenae: http://www.greekmythsgreekmythology.com/the-royal-house-of-the-atreids-in-mycenae/

slide #20: photograph of gold mask of Agamemnon:

http://www.artchive.com/artchive/G/greek/agamemnon.jpg.html

Slide #21: Vase painting portraying Cronus: http://www.johnuebersax.com/plato/myths/statesman.htm

Slide #22: Cranach painting: Golden Age of Man: http://creativityandhealingkalina.blogspot.com/2012/06/golden-age-ages-of-man-in-mythology-and.html

Slide #25, etching fy Virgil Solis of the Iron Age:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Virgil_Solis_-_Iron_Age.jpg

Slide # 34, photograph of carded wool made into a ‘rolag’ and ready for spinning:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carding#mediaviewer/File:Rolag.jpg

Slide #35, woman spinning and drawn on 5th century B. C. vase:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hand_spinning#mediaviewer/File:Woman_spinning_

BM_VaseD13.jpg

Slide #37, and following, portrait of Machiavelli:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli